Why My Husband and I Started Searching for Another Woman

One woman's infertility taught her, among other things, how men really look at the opposite sex.

At the age of 37, I finally began looking at women the way men do. "Check out the Russian girl," I tell my husband.

"Yeah, but look at her chin," he says. "How about this Slovak girl?"

"Too big. Why do you think there's no photo of her from the waist down?"

We're huddled in front of my laptop on the porch of our house in Massachusetts, scrolling down a website loaded with photos of beautiful, lithe young women. It feels somehow illicit, as if we're casting about for a threesome, but unfortunately we're not. We're looking for an egg donor. There is a ruthlessness to our search—is she pretty enough? tall enough? smart enough?—because we are, in effect, engineering our little family.

Our battle with infertility began four years ago. I was 33, my husband 44. We tried everything: hormones, artificial insemination, acupuncture, and herbs. I listened to guided visualization programs on my iPod, lit candles in church, and prayed to saints known to promote fertility. I even wore orange to stimulate my reproductive chakra. One doctor suggested that perhaps I was too thin, so I forced myself to eat huge portions, eggs and bacon every morning, tons of mayo and chocolate. I went up two sizes, but still no baby.

Finally, we decided to brave in vitro fertilization, a grueling, painful process that had me sweating through hormone injections that I gave myself in the belly every night. My husband pretended to be Bruce Lee when he jabbed the one-and-a-half-inch needle into my behind. By now, we'd learned to find the humor in almost every situation.

One cycle passed with no success, then another. After the fifth failed IVF, we turned to a reproductive immunologist who—after numerous blood tests—told us that my immune system might be attacking my embryos. He suggested a controversial procedure called lymphocyte immune therapy, or LIT, that required injecting my husband's white cells just under the skin of my forearms. The treatment was banned by the FDA in January 2002 because, among many reasons, it posed a risk of infecting women with blood-borne diseases. Our reproductive immunologist discreetly gave us the contact information of a doctor in Nogales, Mexico, who'd had luck with many desperate couples like us.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Over the phone, we scheduled an appointment for the first available date, which was a month later. A nurse, who spoke broken English, instructed us to wait at a McDonald's on the American side of Nogales, in Arizona, only minutes from the border. The clinic was too small to find on our own, she explained, so the doctor would pick us up and drive us into Mexico. It sounded shady, but we found many women online who'd said that the LIT treatment in Nogales was safe and that they got pregnant immediately. That was all we needed to hear.

They were right. The clinic was clean, and the procedure was relatively painless. Too bad it didn't work.

I distinctly remember the time I first thought about my biological clock. I was 27 when a feature story came out in one of the weekly magazines, reminding us modern women that our fertility begins to wind down at 28 before plummeting at 35. I was single then, but thought I had plenty of time. That's the thing about being in your 20s—years seem like centuries. I met my husband when I was 29 and married him three years later. It never occurred to me that I needed to hurry. What I didn't know was that our ovaries—just like our faces—age at different rates, and I was one of the unlucky few for whom the biological clock had started ticking earlier than most.

And so here I am, many in vitro cycles later, looking for the eggs of a younger woman. Resorting to an egg donor at first seemed like a denial of my womanhood, but after so many failures, I'm just happy for the opportunity. In my mind it's still better than adoption: Half the baby's DNA will come from my husband, and I will be the one giving birth to my child.

But choosing an egg donor isn't as simple as I'd imagined. It's no fun watching your husband admire other women online—hot young women. We pull up the profile of one gorgeous girl in a sundress. "I'd do her," my husband says, and we laugh. It's a joke, and yet I feel the sting of jealousy. It's been hovering over my head, buzzing humorlessly, since we'd started looking at donor photos. I gather my courage—admitting insecurities isn't one of my strengths—and tell my husband that I appreciate his efforts to relieve the tension. "But please," I say, "I feel like spoiled goods as it is."

He's sweet about it and tells me that if my photo were there, I would be the one he'd pick.

We continue combing the databases of donor egg agencies. I'm surprised how much looks matter to me. I'd gone into the process thinking that I wouldn't care for such frivolities—all I want is a child, and it doesn't matter how he or she looks—but it turns out that I do care. I find myself looking for girls who resemble me. I've always imagined that one of the joys of having children is recognizing your partner's features in their faces, and I want that for my husband. I've never before thought much about my Bulgarian heritage, but as I search for someone to give me her eggs, I become a born-again Bulgarian. I want to find a donor whose features bear a hint of the Slavs and ancient Bulgars who make up my genetic heritage. Even one odd trait—like red hair—will disqualify a girl. I am looking for someone who could at least pass for my cousin.

And I can't help myself: I want the girl to be hot. Not too hot—I don't want my kids to look as if I'd stolen them from Angelina Jolie—but hot enough so that their adolescence won't be a painful horror show. It's hard enough to give your children your own physical flaws. But when you actually have a choice in the matter, it feels almost cruel. Genetic health, of course, is our top priority, but agencies already preselect for that. Intelligence is also high on our list, but it's a hard thing to gauge based on a girl's education and career. And character traits—is she stingy? selfish? dishonest?—seem more a matter of upbringing than genes. So we're left with beauty—and beauty is what we look for.

But now that I'm in the business of evaluating women in the crass physical ways that men do, I find that I can't stop. I check out young women everywhere: on the street, on the subway, even at the fertility clinic (some of the young nurses look like ideal donors). At dinner with a friend, I am captivated by the hostess, who approaches us with an easy smile. She's in her early 20s. Petite. Almond-shaped green eyes. Wide Eastern-European cheekbones. As soon as she walks away, I turn to my friend: "I want her eggs!" Two days later, I meet a gaggle of young Russian students at a party. One of them is particularly beautiful, and I can't take my eyes off her. She tells me that last summer she traveled with a group of Bulgarian students and picked up a Bulgarian poem that she recites in a buttery Russian accent. I'm in love.

Evolution theory suggests that men are drawn to young girls because they are so fertile. I used to dismiss it as a lame justification that men use to date women half their age. And yet here I am, hunting down young game, calculating women's worth based on age and looks. It's foreign territory, and I'm not entirely comfortable with this kind of predatory mind-set. But I am on my own evolutionary track, salvaging my own motherhood as best I can.

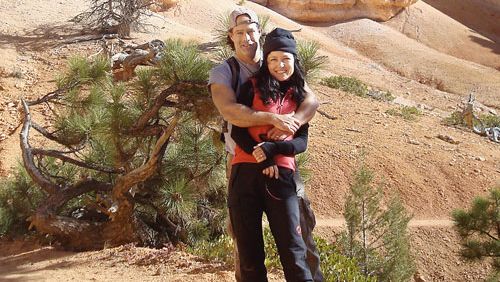

Back on our porch, my husband and I put away the laptop and take a walk in the woods. The rustle of branches, the smell of pine needles on the ground, the setting sun on my husband's face. And I cease to be me and become them, both my ancestors and my future offspring, in awe at the end of another day. Wherever my children come from, I finally realize, there will be the magic of our little family standing together before the vast, heartless universe.

Daniela Petrova is a New York—based writer. Her poems, short stories, and essays have appeared in newspapers and anthologies, including Best New Writing 2008 (Hopewell Publications) and The Christian Science Monitor. She is currently working on a novel.

-

What to Know About the Cast of 'Resident Playbook,' Which Is Sure to Be Your Next Medical Drama Obsession

What to Know About the Cast of 'Resident Playbook,' Which Is Sure to Be Your Next Medical Drama ObsessionThe spinoff of the hit K-drama 'Hospital Playlist' features several young actors as first-year OB-GYN residents.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Duchess Sophie Stepped Up to Represent King Charles at Event Amid Calls for King Charles to "Slow Down"

Duchess Sophie Stepped Up to Represent King Charles at Event Amid Calls for King Charles to "Slow Down"The Duchess of Edinburgh filled in for The King at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

By Kristin Contino

-

See the Top-Scoring WNBA Draft Looks

See the Top-Scoring WNBA Draft LooksThis year's rookie class came to win.

By Halie LeSavage

-

COVID Forced My Polyamorous Marriage to Become Monogamous

COVID Forced My Polyamorous Marriage to Become MonogamousFor Melanie LaForce, pandemic-induced social distancing guidelines meant she could no longer see men outside of her marriage. But monogamy didn't just change her relationship with her husband—it changed her relationship with herself.

By Melanie LaForce

-

COVID Uncoupling

COVID UncouplingHow the pandemic has mutated our most personal disunions.

By Gretchen Voss

-

15 Couples on How 2020 Rocked Their Relationship

15 Couples on How 2020 Rocked Their RelationshipFeatures Couples confessed to Marie Claire how this year's many multi-stressors tested the limits of their love.

By Sherry Amatenstein, LCSW

-

A Marriage Made on Promises Not Plans

A Marriage Made on Promises Not Plans"Six days before my dad was supposed to walk me down the aisle, I curled beside him in his hospital bed."

By Laura Townsend

-

How to Fight Fair In Relationships

How To Our resident psychiatrist lays out the rules to fighting fair.

By Samantha Boardman

-

They're Single. They're Straight. They're Friends. And They're Having a Baby.

They're Single. They're Straight. They're Friends. And They're Having a Baby.You want a child. You don’t want to do it alone. What do you do? For an increasing number of women, the answer is raising a kid with their BFF.

By Sarah Treleaven

-

My Husband Left Me After 16 Years—So I Bought a Fixer Upper Across the Country

My Husband Left Me After 16 Years—So I Bought a Fixer Upper Across the Country"This house could hold me. It had survived being abandoned, too."

By Danelle Lejeune

-

A Decade ’Til \201cI Do\201d

A Decade ’Til \201cI Do\201dDarlena Cunha had been married for 10 years when she decided it was finally time to have a wedding.

By Darlena Cunha