Party to the Death

Looking for adrenaline, hordes of American students and recent grads are descending on the world's latest party capital, Vang Vieng, Laos, and dying for a good time.

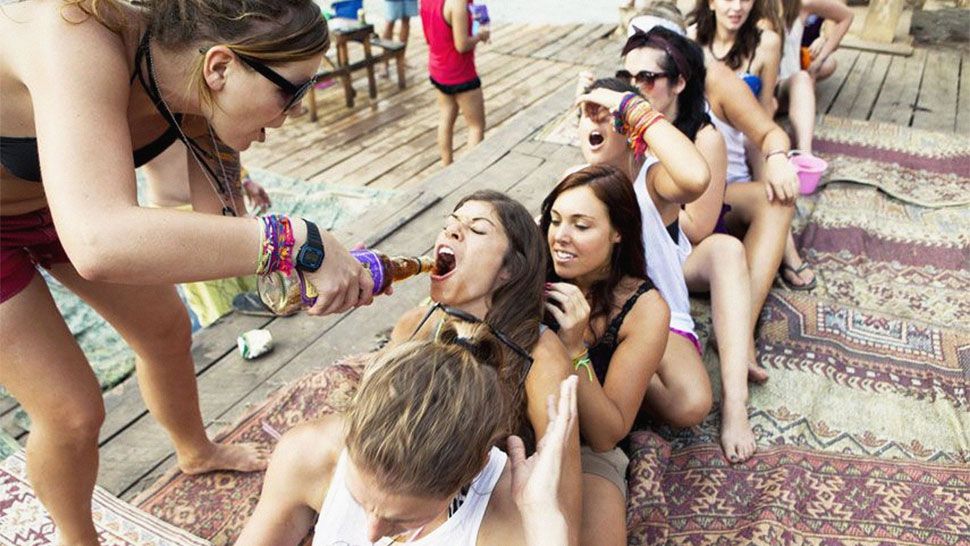

In the baking midday sun, a bunch of bikini-clad Western women play a drinking game called "Train to Oblivion." Giggling and squealing above loud party music, they clutch one another's waists while a bar worker pours whiskey down their throats. The winner is the last woman to pass out, fall over, or throw up on her sequined flip-flops.

Panama City Beach? Cancun? No: Vang Vieng, Laos — the world's most remote party town. Deep in the jungle of one of Southeast Asia's poorest countries, this former farming village is a hot destination for 20-something globe-trotters. A trip there literally ends in oblivion for some. Amid the free-for-all atmosphere of sex, drugs, and alcohol, travelers are dying here in alarming numbers.

"Vang Vieng is crazy," says Celine Laheurte, 23, an art school graduate from New York who is sitting at one of the area's many bamboo bars. "It's like the spring break you never had." Around 170,000 travelers from America and Europe flock to Vang Vieng every year to go tubing — riding tractor-tire inner tubes down the Nam Song river. A four-hour drive from the Laotian capital, Vientiane, the area boasts gorgeous limestone mountains, caves, and lagoons.

But the biggest draw is 24-hour partying by the river. In 2011, at least 27 tourists, around half of them women, lost their lives here. Most died from drowning or from cracking their skulls on rocks after performing drunken water stunts on the zip lines, slides, and rope swings that have sprung up beside the bars. "Many people get so wasted they take incredibly dumb risks," says the dark-haired Laheurte. "I'm being really careful."

A senior doctor at the local hospital says five to 10 backpackers every day suffer nasty injuries. "One woman scraped all the skin off her face on the rocks," he recalls. Stories of near-deaths abound. A traveler named Mike relates on a blog how his girlfriend fell 40 feet from a rope swing, narrowly missing rocks when she landed. "Three feet to the left, she would have been dead."

Partying at the river kicks off around midday. At about $1 per bottle, the local Lao-Lao whiskey is so cheap it's served in children's beach buckets. Most restaurants openly offer "happy" pizzas and "magic" shakes or teas laden with marijuana, opium, or mushrooms.

"It's great fun if you're not stupid," says Laheurte, who's traveling solo around Southeast Asia as a graduation gift from her parents. But the New Yorker admits she's shocked by the wild behavior of many of the women. "Some girls totally lose all their inhibitions." Travelers play drinking games and paint one another's near-naked bodies with obscene slogans. Some of the most offensive include "I will be your c**t" and "You can f**k me without a condom." Others are unprintable.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

British backpacker Emily Atherton, 34, a short blonde with hearts spray-painted on her body, says there's peer pressure to behave outrageously. "You're boring if you don't drink or do crazy stunts." Promiscuity is also rife, she says, with women sleeping around to prove they're "just as wild" as men. "I met one girl here who told me she'd slept with a different guy every night, and she'd never once done it sober."

While many travelers dismiss their behavior as high-spirited fun, it's far less amusing for Laotian villagers. Few locals benefit economically from the tourist invasion — a majority of the bars are owned by the town's most powerful people. Traditional Lao culture is conservative, and many villagers are offended by the scantily clad partyers. "In Laos, we cover our arms and legs," says schoolteacher La Phengxayya, 25. "I don't want my 4-year-old daughter to copy the foreigners."

The tragedies are thought to have brought bad karma, too. The Nam Song river used to be a serene spot for bathing and fishing. Today, few locals will go near it. As in much of rural Asia, animistic-Buddhist beliefs in powerful spirits that inhabit nature are still common. "We don't want to swim in the river anymore," explains Phengxayya. "We believe there are evil spirits in the water because so many young foreigners have died there."

She says the locals have a refrain for when travelers stagger back into town after a day of debauchery, covered in grubby bandages and wearing skimpy, ragged clothes: "The zombies are coming."

-

The Wild Ride of Carrie Coon

The Wild Ride of Carrie CoonLaurie's deep-set insecurities come to a head in episode 7 of 'The White Lotus,' allowing the actress to turn a "dark night of the soul" into an illuminating time.

By Jessica Goodman Published

-

Joshua Jackson Won't Let His Daughter Watch 'Dawson's Creek'

Joshua Jackson Won't Let His Daughter Watch 'Dawson's Creek'"She's going to get all sorts of ideas."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Why Kate and William Will Be Making More Joint Appearances

Why Kate and William Will Be Making More Joint AppearancesA royal expert weighed in on their plans, calling them "the world's most glamorous royal couple."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

For Teachers, Going to Work Can Mean Life or Death

For Teachers, Going to Work Can Mean Life or DeathStefanie Minguell, a COVID survivor and second grade teacher in Florida's Broward County, almost died of COVID-19 and is immunocomprised. When she teaches in the classroom, she’s forced to choose between her health and her students.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Periods Don’t Stop for Pandemics—And Neither Have Our Nation’s Moms

Periods Don’t Stop for Pandemics—And Neither Have Our Nation’s MomsPolicies touted in the $3.5 trillion budget plan and other Congressional bills are missing a core component of maternal well-being: menstrual access and health.

By Christy Turlington Burns Published

-

Your Abortion Questions, Answered

Your Abortion Questions, AnsweredHere, MC debunks common abortion myths you may be increasingly hearing since Texas' near-total abortion ban went into effect.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Texas Abortion \201cSnitch\201d Site Is Having a Bad Weekend

The Texas Abortion \201cSnitch\201d Site Is Having a Bad WeekendFirst it gets flooded with sexy Shrek memes, then the web host tells it to get lost.

By Cady Drell Published

-

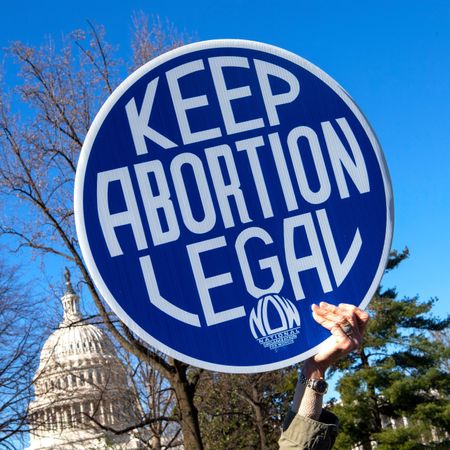

The Anti-Choice Movement’s Aims Are Out in the Open: End Roe, Rip Away Reproductive Freedom

The Anti-Choice Movement’s Aims Are Out in the Open: End Roe, Rip Away Reproductive FreedomToday, 228 U.S. senators and representatives explicitly asked the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade.

By Adrienne Kimmell Published

-

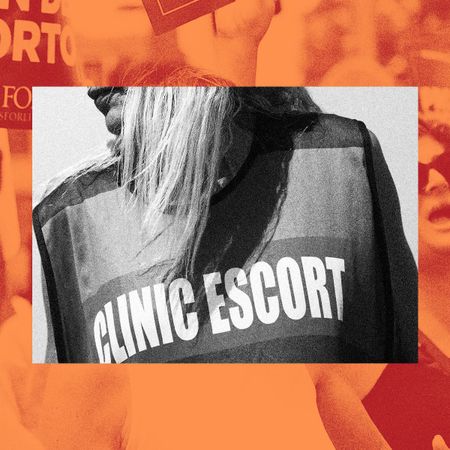

Standing Between Care and Violence

Standing Between Care and ViolenceAbortion-clinic escorts and defenders serve as human shields protecting patients from angry, aggressive protestors. Now, with emboldened extremists and the COVID crisis, they face more danger than ever before.

By Garnet Henderson Published

-

What's at Stake for Abortion Rights in the 2020 Election

What's at Stake for Abortion Rights in the 2020 Election"Everything is on the line in this election—our health, our rights, our bodies, and our futures."

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Power to Decide Launches Abortion Finder Tool

Power to Decide Launches Abortion Finder ToolAmid legislative attacks on our reproductive health, this tool helps women find verified abortion care providers across the country.

By Rachel Epstein Published