What Happened to These Children of War?

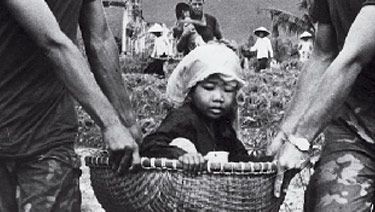

Children of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam.

In the spring of 1975, U.S. forces withdrew from Vietnam, leaving behind an estimated 50,000 children they'd fathered with Vietnamese women. In the following years, these Amerasians bore the brunt of Vietnamese hatred toward America. Today, thousands of half-American women are stranded in a country that doesn't want them. Life has not been kind to the bui doi, or "children of the dust." Bi Thi Loan, 39, was rejected by her own family.

I am the child of a black American soldier, Ali, and a Vietnamese woman. My mother was already married when she met Ali. Her husband was a soldier in the South Vietnamese army. He left on operations a lot, so my mother had to make a living. She worked in a bar - that's where she met my father. About a year after she met him, I was born. Two months later, my mother gave me to my grandmother in Minh Hai province to raise me, because her husband disliked me so much.

In Minh Hai, I was sent to work in the rice paddies at age 12. I had to do the hardest work - pulling the plow - myself, because we were too poor to buy an ox. My uncle, a Viet Cong veteran, hated me so much, he beat me on the head with a stick every time I failed to pull the plow. I still suffer from headaches today. When I was 15, I went home to see my mother. I begged her to take me back, to let me live with her. But my stepfather wouldn't allow it. So I returned to the rice paddies.

At age 26, I married my husband, Pham Van Thang. We moved to Saigon, where he sold dried red peppers for a living. Today he works transporting goods in a cart he attaches to a tricycle. He earns about $1.25 a day. I do not have a job right now; without formal training, I can only do manual work. I am going back to school, though. I have completed fifth grade, so I can read and write. Meanwhile, I raise our four children.

We live in a little house inside a cemetery. We have no beds - we sleep on the floor. Our monthly income is $38, which must feed 10 people (my mother-in-law, my brother-in-law and his wife and baby all live with us). Every day, we go to restaurants and look for leftover food that is thrown away. We wash it and cook it again in order to have something to eat.

Who will help us get out of this misery? I don't know. I really want to find my father, Ali. If I ever meet him, I will surely cry and tell him how I have suffered through the years. I would like to go to America. My children hate going to school here, because they get picked on for looking black.

In Vietnam, people are of two minds about Americans. Most think they are not bad - they have done much to help the poor people in Vietnam. But others still dislike Americans. They see Amerasians as children of the enemy - and for that, we are treated badly.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Shocked by reports of Amerasian abuse in Vietnam, U.S. legislators passed the Amerasian Homecoming Act in 1987, allowing more than 26,000 children of American soldiers to immigrate to America. But plagued by illiteracy and language barriers, fewer than 40 percent pass the U.S. citizenship exam, meaning they cannot vote, they risk deportation, and they receive only limited government aid. For Thu Thuy Le, 33, life in the U.S. has brought new hope - but also new struggles.

My mother was a high school student when she met my father, a U.S. soldier stationed in Hue. She said he was handsome and charming, just a year older than she was. They lived together until eight months after I was born, in 1971.

I don't have any photos of my father. When the North Vietnamese troops took over my mother's hometown of Quang Tri, they beat her for having had a relationship with an enemy U.S. soldier, then they tore up her photos. For as long as I can remember, I was teased for being Amerasian. Other kids called me a half-breed. Even the teachers were cruel. When I was 9, I raised my hand to ask permission to use the bathroom, but the teacher didn't let me go, and I wet my pants. Eventually, I stopped going to school. Now I can only write my name.

My mother had two more children by a Vietnamese boyfriend - my brothers, Do Van Thanh, 25, and Do Van Ty, 20. We lived in Lao Bao, surviving off the vegetables and rice we grew ourselves. When I was 18, my mother died in my arms from an asthma attack. Her family took my brothers in, but I wanted to go to America. I'd heard of other immigrants who had sent money back; I thought I could provide for my brothers and eventually have them join me.

To get to the U.S., I first went to Saigon in 1993, where a family "adopted" me because they also wanted to go to America. This is how it was for Amerasians who couldn't read or write: I needed someone to help me with the visa application, and these people wanted a ticket to America in exchange. They did all my paperwork and changed my name to theirs. But we didn't have our "family" stories straight when embassy officials questioned us, so I was forced to go to America alone. Because I changed my last name on my documents, it is no longer the same as my biological brothers', so I can't prove they are my family - meaning I can't bring them to the U.S. to join me.

Today I live in Washington, DC, where I clean a dentist's office every day. I live with a friend's uncle and my two children. They were conceived through relationships I had when I got here, but they are my responsibility now. I send money back to my brothers in Vietnam - the youngest finishes high school this year. My life here is difficult, but I won't share this with my brothers. They ask me, "Sister, do you have money?" I say, "Yes!" I want them to feel like I've made it so they won't be sad. But it's hard ‑- I get $100 a month in food stamps, and I don't have any health insurance.

Sometimes I think about my father. I want to know my flesh and blood; I don't care whether he is rich or poor. If he were homeless, I'd bring him in and take care of him. If he wanted to give me even just $1, I'd take it, because he's my father, but I'd never ask. I'd just cry if I met him. Not in front of him, though - I'd wait until he left, then cry.

America is my home now. I have enough to eat and can send money back to my family. As for my dreams and hopes, I dream about citizenship. Previous U.S. presidents sent soldiers to fight in Vietnam; that's why we Amerasians exist. The current president should accept us as citizens. My blood and my father are American. And my children are American. So I want to be American, too - to really, finally, be part of the same family.

On April 2, 1975, Ed Daly, president of World Airways, made a radical decision: He would use his own plane to airlift orphaned children out of Saigon. The U.S. government refused to sanction the risky evacuation. The Saigon airport shut off runway floodlights to prevent takeoff. Fearing enemy gunfire, the pilot turned off the plane's headlights. In total darkness, World Airways flight "Operation Babylift" raced down the runway - and into history. Fifty-seven children were safely evacuated, and the media attention prompted President Ford to begin airlifting orphans the next day. Over the next several weeks, more than 2,700 children were evacuated. Tanya Bakal, now 31, was on the unauthorized flight.

I never met my father, an American soldier. I was 18 months old when my mother left me on the steps of a convent in Vietnam. She pinned a note to my chest, asking the nuns to watch over me. I never saw her again. I arrived in the U.S. a really sick baby. I had a hole in my eardrum, parasites in my stomach and a severe eye infection. But I survived. I was adopted by a family in Marietta, GA.

As a kid, everything frightened me - especially the sound of helicopters. There were other issues: I'd crawl into cardboard boxes around the house to sleep and wake screaming from nightmares. My parents would find food hidden in my drawers that I'd "stolen" from the kitchen. All were survival instincts from life in Vietnam.

Marietta was a conservative town. I tried to fit in - I wouldn't play with other Asian kids, because I didn't want to seem more "different" than I already felt. Things got bad in high school, though. One time, I was working at a store and a man came in for beer. I was only 16, so I asked him to scan his beer himself - legally, I wasn't allowed to. He started yelling these awful racial slurs at me, calling me a "gook." I'd never even heard the word before. I just stood there. That's what I always did when people teased me - I pretended it wasn't happening. Over time, it took a toll on my self-esteem.

A year ago, I started looking for my real parents. I'm married now, with three kids. Everyone in my family has a history except me; it's an empty feeling. The organization helping me, the MilkCare Foundation, posted my face on TV in Vietnam. For months, nothing. Then a few weeks ago, two women came forward saying they could be my mother! It's crazy. I mean, what are the chances? Still, if I ever meet my mother, I will say, "Thank you for loving me enough to try to protect me. Thank you for putting me somewhere you thought I would be safe."

These orphaned daughters of U.S. servicemen were evacuated from Vietnam in 1975. This June, some will return to their birthplace as part of a U.S. diplomatic mission. Here, they share their stories with Marie Claire:

"My mother and I were still in our village when the Viet Cong attacked. The village was demolished, and my mother and I got separated. That was the last time I saw her. I was 3. The orphanage took me in because I had been abandoned. The feeling of being left alone is still my biggest fear today. I always need to know where people are. It has never left me." -Tia Keevil, 34, nurse, New York

"I was adopted by a couple in Missouri. In college, I was a cheerleader for the St. Louis Rams. I like to think I raised the profiles of Amerasians - not many other cheerleaders looked like me! Now I am back in school, studying architecture. I owe my confidence to my adoptive parents. I grew up in a predominantly white area, but I was surrounded by open-minded people. Like them, I don't see race or color; I see the person." -Lyly Koenig, 30, grad student, California

"I was on one of the last planes out of Saigon. My birth mother gave me up to give me a better life. I was born with a cleft lip and needed medical attention - I was almost a year old and weighed only nine pounds. Doctors gave me a 50 percent chance of surviving, but my parents adopted me anyway. I will always be grateful for them taking that risk." -Kimberly Louie, 30, insurance verification specialist, Colorado

You Can Help These Women Amerasian Child Find Network, Jon Tinquist at the AAHOPE Foundation or Boat People SOS.

-

Trade Your Multi-Step Lip Care Routine for One Do-it-All Gloss

Trade Your Multi-Step Lip Care Routine for One Do-it-All GlossHydration, pigment, and longevity.

By Siena Gagliano Published

-

I’m Wearing These On-Sale Summer Tops With Everything This Summer

I’m Wearing These On-Sale Summer Tops With Everything This SummerFrom denim to skirts, these under-$150 finds work with everything.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

My Afro and I Have a Summer Muse—and Her Name Is Kerry Washington

My Afro and I Have a Summer Muse—and Her Name Is Kerry WashingtonMy curls understand the assignment.

By Ariel Baker Published

-

For These Ukrainian Women, Their Weapons Are Their Smartphones

For These Ukrainian Women, Their Weapons Are Their SmartphonesBy collecting cell phone video straight from the front lines, Dattalion shows the unfiltered horrors of the war.

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

"It Is Hell."

"It Is Hell."Marie Claire Ukraine staffers on what they’re enduring as bombs fall on their beloved country.

By Galia Loupan Published

-

Clarissa Ward on What It's Really Like to Report Live From Ukraine Right Now

Clarissa Ward on What It's Really Like to Report Live From Ukraine Right NowThe network's chief foreign correspondent on pivoting from Kabul to Kharkiv and Kyiv.

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

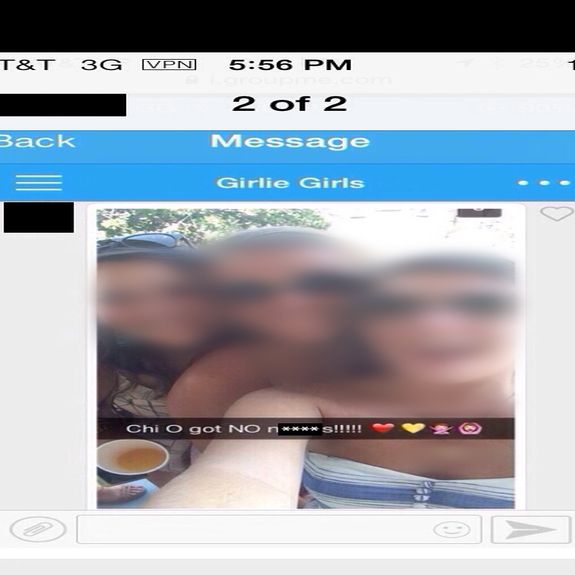

Racist Photo Sent in Wake of Sorority Rush at University of Alabama

Racist Photo Sent in Wake of Sorority Rush at University of AlabamaUniversity of Alabama and national chapter of the sorority in question are investigating image captured from social networking site.

By Kayla Webley Adler Published

-

This Act Could Put an End to Anti-Abortion Legislation

This Act Could Put an End to Anti-Abortion LegislationWomen's right to choose is constantly at stake—but this might the solution.

By Diana Pearl Published

-

Yet Another Blow to Birth Control Coverage

The Supreme Court's latest decision will limit a key benefit for women.

By Laura Cohen Published

-

California Audit Finds Universities Are Failing Students Who Are Sexually Assaulted

California Audit Finds Universities Are Failing Students Who Are Sexually AssaultedState auditor report says colleges must do more to prevent, respond to, and resolve incidents of rape and sexual assault on campus.

By Kayla Webley Adler Published

-

Sexual Assault Survivors Speak Out Against Campus Rape

Sexual Assault Survivors Speak Out Against Campus Rape"This is the civil rights movement of our generation"

By Allison Ellis Published