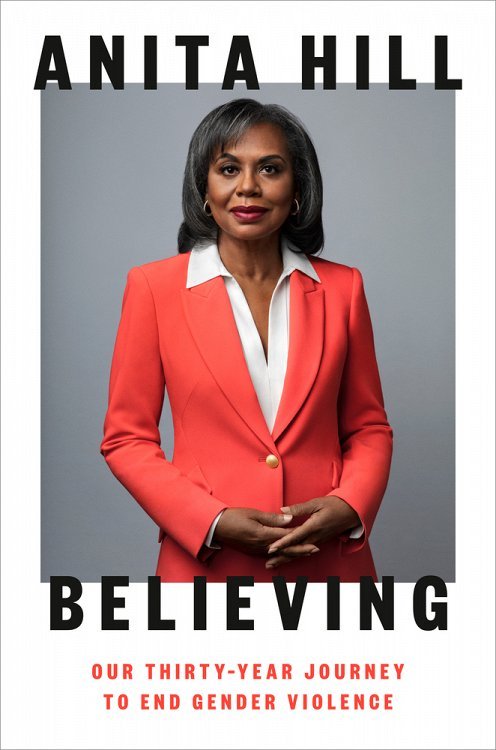

Anita Hill Believes We Can End Gender Violence

Three decades after her landmark testimony in the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings, the esteemed professor and lawyer has a message for leaders: The time is now to prioritize anti-gender violence policies.

Trigger warning: This article contains references to sexual assault, sexual harassment, and other forms of gender violence.

When Anita Hill testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee on October 11, 1991, accusing then-U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment, the outcome was anything but favorable. Thomas's ascendance to the highest court in the land, despite the accusations Hill detailed, confirmed how little our society valued women and set a precedent for how our nation would address gender violence moving forward. After the hearings, Hill had to make a choice: retreat back to her "normal life," resigned to the fact that her high-profile testimony made no impact on Thomas's confirmation, or believe that we, as a nation, could do better and work to enact change for future generations.

For the past 30 years, Hill has embraced the latter, reflected in her aptly-titled book, Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey to End Gender Violence (out today). In the book, the Brandeis University professor and lawyer discusses America's gender-based violence epidemic and what has—and hasn't—changed in the three decades since her testimony. Rather than writing a memoir, Hill combines anecdotes from her own experience of sexual harassment with those from other survivors, and translates them into actionable ways in which our country can address gender violence today. Her decision to avoid centering herself in the book and in her advocacy work is partly due to Hill being a private person by nature, but also because she feels compelled to share the extensive training and research she's done on gender violence with the world.

"[My] experience [with sexual harassment] was just the beginning. What propels me is what I know now about the [systemic] problem," Hill tells Marie Claire. "We should be enlisting survivors more not just to tell about their experiences. There is also much wisdom around the solutions and how we can move forward. I want us to be recognized for all of those things that we can offer."

The significance, and perhaps irony, of releasing this book in 2021 is not lost on Hill. Not only has violence against women surged—the pandemic has exacerbated domestic violence, as well as online harassment—but the man who led the Thomas confirmation hearings is now President of the United States. Then there's the near-total abortion ban in Texas, a statute whose constitutionality will likely be determined by this Supreme Court. Had the Senate Judiciary Committee conducted a fair and open hearing following Hill's accusations in 1991 (Angela Wright, another woman who accused Thomas of sexual misconduct, was subpoenaed by the committee but not called upon to testify), perhaps we wouldn't have witnessed history repeat itself 27 years later during the confirmation hearings of Brett Kavanaugh. Or witness the most restrictive abortion law in the country go into effect three years after that (Thomas and Kavanaugh were two of five justices who voted not to block the Texas law from going into effect).

Nevertheless, Hill describes the past year-and-a-half as "a moment of accountability." A time when America might finally be ready to acknowledge that gender-based violence has consequences—not just for women, but for society as a whole. Here, Hill speaks to Marie Claire about prioritizing anti-gender violence policies, her thoughts on the #MeToo movement, and the message she has for fellow survivors.

Marie Claire: In the book, you briefly mention your first face-to-face meeting with Dr. Christine Blasey Ford just over a year after her testimony, and her wish that the Senate will create a new system to handle sexual misconduct complaints. How did the results of Dr. Ford's testimony influence your own hope about ending gender violence?

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Anita Hill: I'm hopeful for a number of things. One of the things that I'm hopeful about is the change in the American public over the last 30 years. When I testified, so many people said that they weren't even aware of the problem of sexual harassment. We've gotten a public that is much more aware, and it's because of many of the activists that have grown up during this period, the amount of attention that is being paid on colleges and university campuses, and a movement inside those campuses. There is a lot to be hopeful for, and the public's reaction to Dr. Ford's testimony—with the majority of the public saying that they did not believe that Kavanaugh should be confirmed—represents that movement.

MC: You spend some time discussing how Black women often feel at odds with their decision to come forward if the accused is also part of the Black community. During the Thomas hearings, how did you grapple with comments about protecting the community at large?

AH: I'm not sure that I personally was able to alone. One of the things that helped me very early on, and I'm eternally grateful for it, is the ad in the New York Times by a group called African-American Women in Defense of Ourselves, which was really a statement about Black women's experiences in this country and our history of abuse. Our history of silencing and denial of our experiences and our pain. It strikes me that when you talk about Black women's experiences, it's a prime example of what I call "grooming" in our culture, where we are led to believe that our pain is not significant. In the book, I write about [former U.S. Senator] Arlen Specter's statement during my testimony that what had happened to me "was not so bad." I think about how often we tell young girls that their problem is not so bad. "You should just ignore it." Eventually when you're told over and over that the problem is insignificant, you internalize that message.

Now add onto that racism, intersectional bias, and discrimination. If you raise a complaint against another person of color, you will be shamed into believing that you are doing something that hurts the community, the race. I hear from young Black women, especially when I'm on college campuses, about the same concern that they cannot come forward if their alleged abuser is another person of color, or specifically another Black person. So everybody is suffering in the community knowing that this problem exists, and we can't have any recourse because of the racist system that we live in. This is a cultural problem and a system problem. It shows in particular how the systems have failed Black women and other women of color.

I mentioned [in the book] the survivors conference that happened this past year that was really a monumental event in terms of where this issue has come over the last 30 years. But one of the things that women of color complained about was that they felt they had no place to go to get all of the problems addressed because the police, in taking their claims, were hostile to them. In many cases, they said they were made to feel as though they had done something wrong. That is just the systematized version of blaming the victim. It has racial implications, it has gender implications, and it's a problem that has to be fixed.

But I also talk about the other side of this in the book, and that is to have young Black men who really do want to be part of this fight against gender-based violence—against sexual assault, sexual harassment, and rape, specifically—but they also know that they can be wrongly accused by law enforcement. All of us are trapped in this system that keeps us less safe because of our race and because of the prevalence of gender violence. That's a complicated problem. So how do we get together? We have to start by giving equal space to have these conversations in a public way where they are not shamed for stepping up, and in a way that says that the community values you and values your voice.

I think about how often we tell young girls that their problem is not so bad. "You should just ignore it." Eventually when you're told over and over that the problem is insignificant, you internalize that message.

MC: With these racial dynamics, it's even more amazing to me that you chose to continue on this path towards ending gender violence. You could have retreated back to your private life, but you chose the public.

AH: I chose the public not really knowing how deep the problem was. In the book, I talk about sexual harassment, but I also talk about all of the other stories that I hear. Like the man who called me almost immediately after the [Thomas confirmation] hearing and said that it reminded him of his problem trying to convince his family that he was being violated by a member of the family, and the denials that they had for his experience and how he was silenced.

I heard that thread over and over again from survivors. It's been 30 years of hearing victims and survivors talk about their own experiences. So what we're talking about is a problem that is a people problem, it's not just a problem of one type of behavior. There are so many elements that victims of sexual harassment, victims of incest, victims of intimate partner violence, and victims of rape all have in common. That's part of the scope of the problem, but in addition it's an institutional problem. We've got military scandals, we've got government scandals, we've got courts scandals, we have scandals in private industries. Name an institution that has been exempt from this problem. What it then comes down to is not just the individual damage and the institutional damage, but families and communities and, ultimately, our nation suffers.

MC: Speaking of which, you talk a lot about the individual vs. the collective, trying to get readers to understand that violence against women ultimately affects everyone. One of the examples you used was tied to the economy.

AH: Unfortunately, that is how our legal system [works]. In the United States v. Morrison case, it all boiled down to the commerce clause, and that really is quite sad. The idea that Congress is only able to pass protective legislation to end violence against women because of its relationship to commerce? That in and of itself is pretty shocking. But the fact that we had all of this evidence that there is an impact on commerce, and the Court still chose to deny that Congress had the authority to act, that's one of the things that I think has to change.

Anita Hill testifies in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991 during the Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas, Hill’s former boss, who she accused of sexual harassment.

Some fixes are longterm, but for now we need changes to procedures. We need changes to the procedure that—if you want to call it that—Christine Blasey Ford fell into, that I fell into, that really hasn't changed that much, if at all. But we also need specific policies that are targeted to the harms that we know have been created. We have statistics that say that 38 percent of people who experience intimate partner violence will become homeless. So we have a housing crisis, we have a health crisis, we have an impact on education. We don't know what the impact is, but we know from the experiences of survivors and victims that there is an impact on their children's education and the family's ability to support itself. All of these things deserve immediate and deliberate attention, but we also need better processes and procedures.

MC: I was struck by your mention that small businesses are exempt from sexual harassment lawsuits. Independent contractors aren't protected either. Should our focus be on advocating for protections at the state level?

AH: There are so many ways that we need to think about solutions, but clearly our systems have failed. It's a systemic problem and the systems that we have in place are in part based on this idea that the problem is "not so big" and "not so important," or it's something that will eventually just go away naturally. As a matter of fact, all of our systems need to be revamped, including the fact that there are exempted businesses in terms of who gets to be held accountable for the sexual harassment and extortion and assault that goes on in our workplaces. One of the things that we have to consider is that independent contractors are a growing body in our workforce today.

MC: In the book, you briefly talk about President Biden's phone call to you in 2019. Have you been able to connect with the Biden administration about advancing anti-gender violence policies since then?

AH: I have not connected with them, nor have they with me. But I'm hoping that this will get enough attention that even though we certainly have numerous other issues that we're addressing right now, that people will understand that this is one of critical importance.

That's why I call the book 'Believing' because I believe in all of the advocacy and the growth that we have done as a society. If we roll all of that together, I believe we can change.

MC: Let's talk about the #MeToo movement. Lately, it's been difficult to analyze the impact of the movement when, for example, people like former Governor Andrew Cuomo have both drafted legislation to combat sexual harassment, and also been accused of sexual harassment. What are your thoughts on the movement as a whole, and do you believe it has changed anything on a systemic level thus far?

AH: The law has been changed and Governor Cuomo has resigned, so why was that possible? It was possible because there was advocacy. It was the movement. Why did he resign? He resigned because there was a system in place for an investigation, there was an explanation of the investigation that took place, there were conclusions that were reached, and there was a recommendation for accountability that came from many voices. As difficult as it has been to read the stories about some of the other involvement with Governor Cuomo, I don't want to take away from the law and I don't want to take away from the procedure that ultimately ended with him resigning.

But what I do want is that, with all of these decisions that are made, they be survivor-focused and enlist survivors in how these processes roll out and how they're developed. Those voices have to be there, and that's the lesson I believe of the last [month]. How do we make sure that what we're doing does not compromise survivors in any way? [The procedures and processes] are what we've been demanding. I believe that's what we need more of in the future, but we need it to come from leaders.

That will only happen if we, as a society, push for it. If the 70 percent of the people who acknowledged Christine Blasey Ford's brave testimony [and] who said, "This is not right. This is wrong. We need to do something. There should be a different outcome" get on board and begin to push for that, I believe it will happen. That's why I call the book Believing because I believe in all of the advocacy and the growth that we have done as a society. If we roll all of that together, I believe we can change.

MC: The near-total abortion ban in Texas is on a lot of people's minds. It feels like the epitome of everything you've described in this book.

AH: There is a direct relationship between [the ban and] violence, and that is the violence that is occurring outside of clinics that offer abortion to women who are seeking the services. That is a form of gender violence. In many cases, the services may be birth control or breast cancer examinations, so that is a very real and direct harm. The policing of women's bodies, especially turning the public into vigilantes, is shocking. It's the singling out of women for entirely different treatment because of their gender.

MC: What message do you want to share with fellow survivors today?

AH: I want them to read the book and understand that part of my believing is believing that we deserve better. We deserve solutions. We deserve recognition of the harm that is being caused to us, as well as to people around us. I want them to believe that [solutions] are possible and that they're going to take a lot of work. They're not going to be instant, there's no one magic pill that will cure everything. You've got to consider a whole bunch of things, including racism and sexism and class bias and homophobia because we come with all different identities as whole people. I want them to see themselves in this work, but I also want them to be hopeful that things can change for their children, even if not for them.

Interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, RAINN—the nation's largest anti-sexual violence organization—is available 24/7 for confidential support. Call 800-656-4673 or use the org's online chat tool to talk with a trained staff member.

Related Stories

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.

-

I Used Nordstrom’s Sale Section to Craft 7 Perfect Summer Outfits

I Used Nordstrom’s Sale Section to Craft 7 Perfect Summer OutfitsThese are formulas you can rely on.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

Your Syllabus Guide to the 'Weak Hero Class 2' Cast—Meet the Rising K-Drama Stars Playing the Students of Eunjang High

Your Syllabus Guide to the 'Weak Hero Class 2' Cast—Meet the Rising K-Drama Stars Playing the Students of Eunjang HighSo many exciting names join Park Ji-hoon in the second season of the Netflix hit.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Prince William and Kate Middleton "Continue to Push Boundaries"

Prince William and Kate Middleton "Continue to Push Boundaries""They definitely have a different dynamic compared to other royal couples."

By Kristin Contino

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

The 2022 Midterm Elections: What to Know Ahead of Election Day

The 2022 Midterm Elections: What to Know Ahead of Election DayConsider this your guide to key races, important dates, and more.

By Rachel Epstein

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

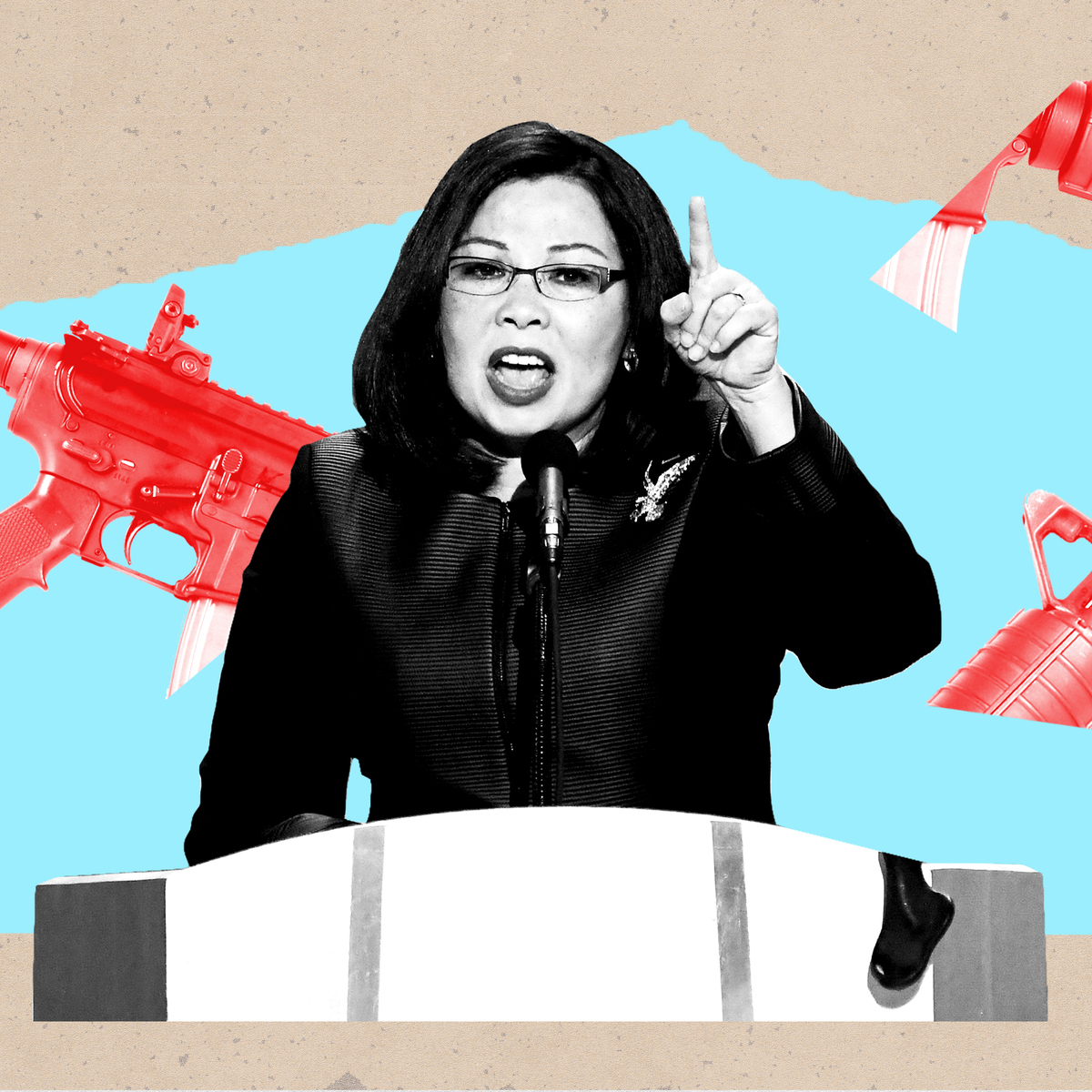

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

This Bill Wants to Stop Anti-Abortion Groups From Getting Your Private Data. Period

This Bill Wants to Stop Anti-Abortion Groups From Getting Your Private Data. PeriodPost-Roe period tracking apps and search history suddenly have serious implications.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Breaking Down President Biden’s New Executive Order on Abortion Rights

Breaking Down President Biden’s New Executive Order on Abortion Rights\201cWe feel really strongly, particularly given the tremendous amount of legal chaos that has ensued since this decision, that it’s incumbent on us to be careful.\201d

By Lorena O'Neil

-

Post-Roe, Pregnant People Will Become Suspects

Post-Roe, Pregnant People Will Become Suspects\201cWe anticipate a very dramatic increase in the rate of criminalization of all pregnancy outcomes.\201d

By Lorena O'Neil