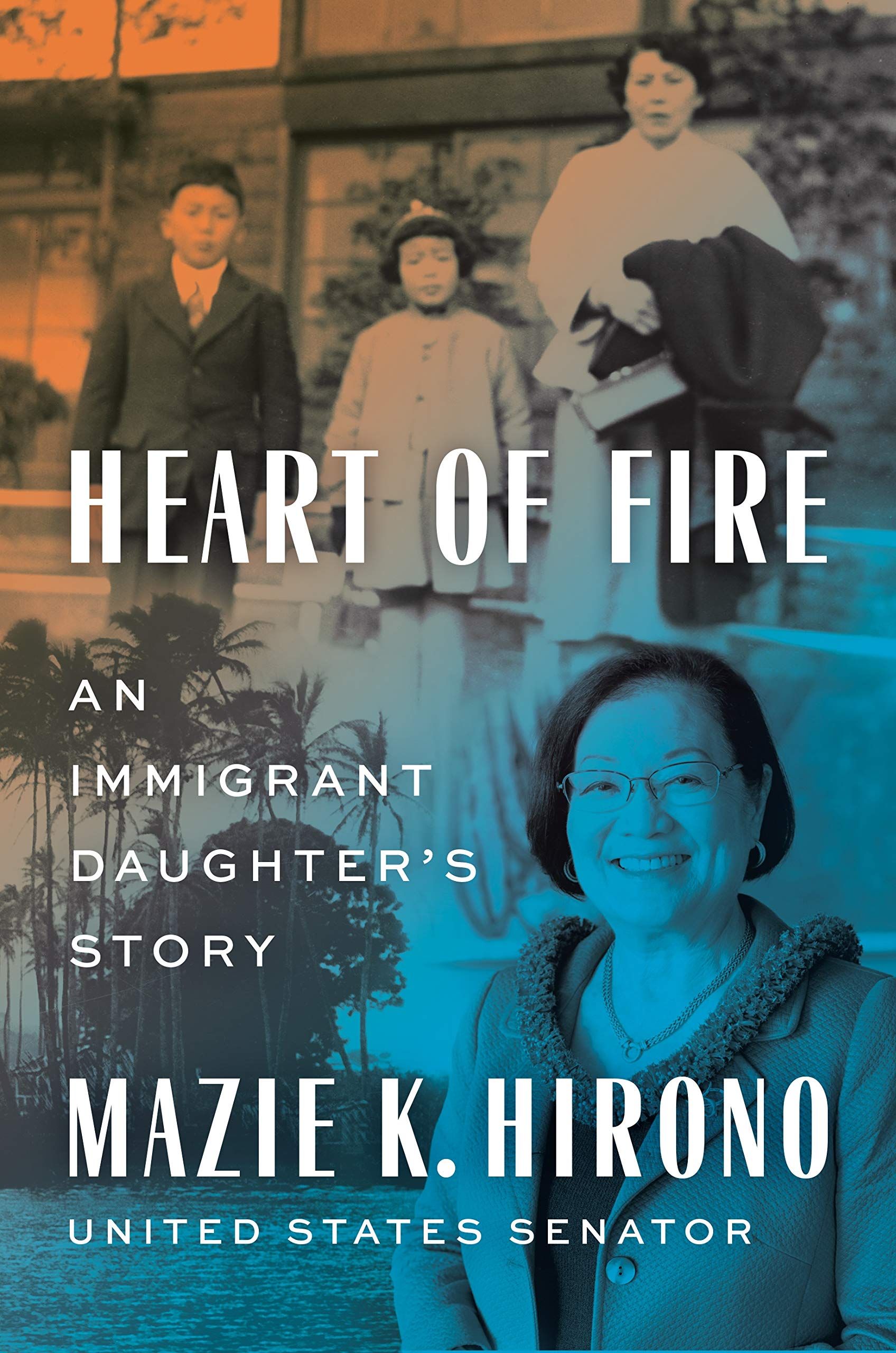

Senator Hirono on Her Journey to the U.S. Senate and Having a "Heart of Fire"

At first glance, 'Heart of Fire' is a political memoir. At its core, it's an ode to a mother who changed her daughter's life.

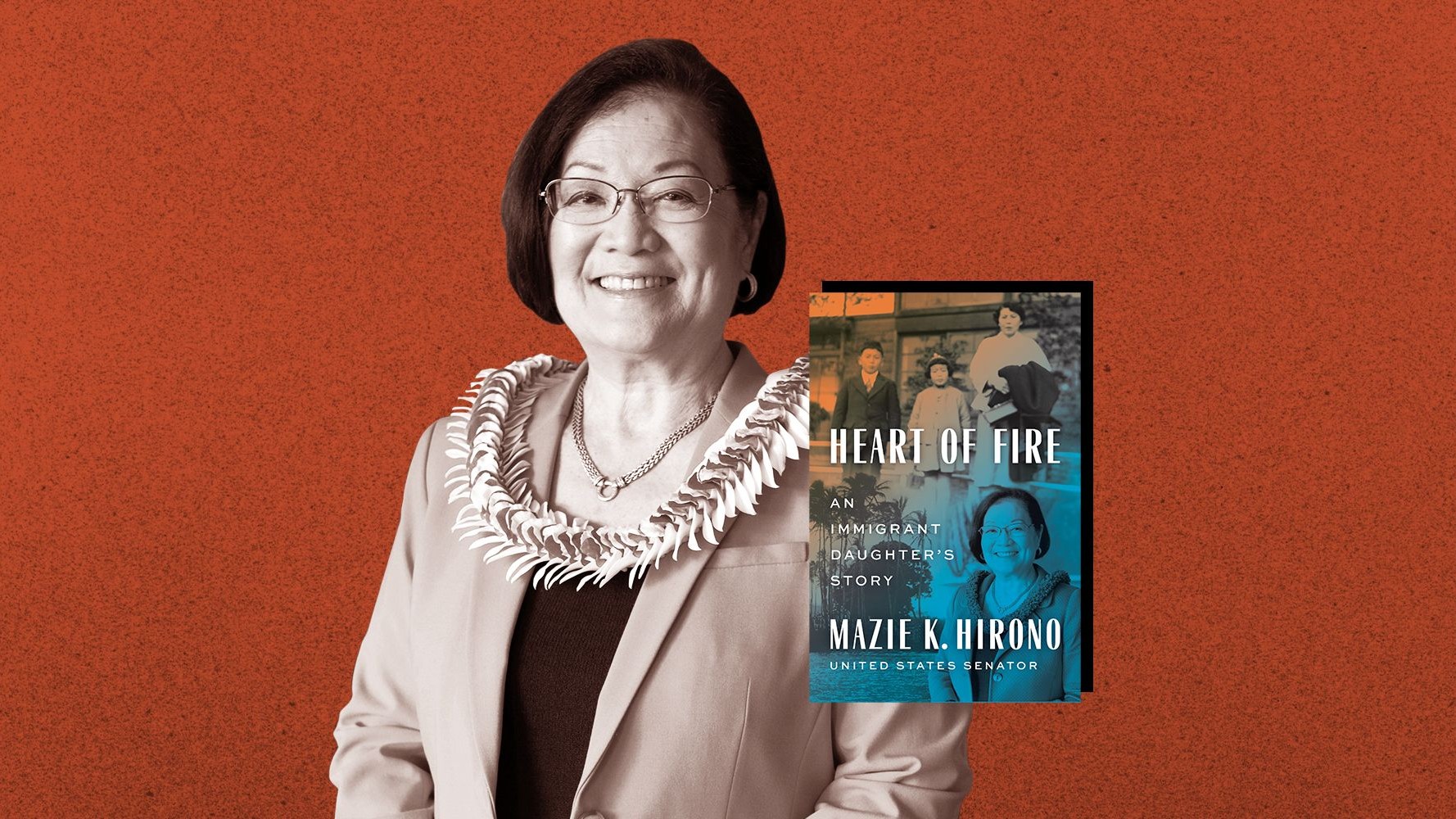

She said goodbye to her grandparents and her 3-year-old brother and the ginkgo trees and the only life she knew in Fukushima, Japan. Then 7-year-old Keiko Hirono, later known as Mazie K. Hirono, boarded an iron ship with her mother and older brother on an afternoon in March 1955 and crossed the Pacific Ocean to a new life in Hawaii. Had it not been for her mother, Laura Sato Hirono, who made the decision to move her family to her own birthplace to escape her husband, known for his alcoholism and gambling, Mazie K. Hirono might have never become a Hawaii State House Representative or Hawaii's lieutenant governor or a U.S. House Representative or the first Asian American woman and Japanese immigrant to serve in the U.S. Senate.

Nearly seven decades since she made a home for herself in the United States, Senator Hirono, 73, will publish her memoir, Heart of Fire (out tomorrow). While the memoir, which her husband encouraged her to write, is an intimate recount of the senator's life, it is also an ode to her mother who, as Senator Hirono writes, "never wavered in her faith that I could invent for myself any life I choose." Her mother, she says, is the person who most embodied this "heart of fire": a fighting spirit of determination, perseverance, and resilience.

Heart of Fire will be shared with the world just one month and a day after Senator Hirono's mother passed away at the age of 96. The senator feels at peace knowing she created this 416-page capsule of both her mother and her grandmother's spirit—"With my mother in the condition she was in, I really felt like this was a good time to tell her story and that of my grandmother, and I'm glad I did"—while diving deep into her journey to the outspoken political figure she is today.

Ahead of the book's release, Senator Hirono spoke to Marie Claire from her home in Hawaii about her reputation in the Senate, the special moment she shared with Dr. Christine Blasey Ford after the Kavanaugh hearings, and how we can all channel the "heart of fire" within us.

Marie Claire: Was there a specific moment in your life that you realized you had a "heart of fire?"

Mazie Hirono: One of my favorite poems is "The Road Not Taken" by Robert Frost and that really exemplifies—"two roads diverged in a wood, and I took the one less traveled by"—how I feel. It's been a journey for me to do things that were different, but always supported by my mother. She knew she didn't have the daughter that was going to get married and do this much more traditional kind of role for women of my time. This led to my brother saying to her at one point (I think I was 30 at the time), "When is Mazie getting a real job?" My mother never pressured me. She just supported me in all of the strange things that I would do, like politics. There weren't a lot of women getting involved in politics, running people's campaigns and all that.

MC: In the book, you talk about how your objective was never to become a wife and a mother.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MH: Well, even if I had this very courageous, independent mother, there's still sort of the expectations of the dominant culture and those expectations were that women of my generation, even if we went to college, we'll get married and have children. Our professions would be more in line with teaching or nursing. Both are very wonderful professions, but not ones that I was particularly interested in or felt that I could do. I write in the book about reading The Feminine Mystique, and I can say that a light bulb went on and I thought, Why am I even thinking that I'm going to get married and do all that? That's when I decided that I'm not going to expect some guy to take care of me.

MC: You seem to have a level of composure no matter how tough things get, especially with the difficulty of campaigning and raising money. Were there any particularly difficult moments when you questioned whether or not you could continue on this path of public service?

MH: Once I decided to seek public office, I decided I was going to do everything I could during the time that I was in office. There are a lot of people I know who are always looking for the next big race and plan for it. I did not do that, which made my life a lot harder when I did make some of those kinds of decisions. We should not be waiting around for, "When I get that position," "When I get that chairmanship." Forget that. Just do what you can in the here and now.

My husband and I often talk about how [no one] would have predicted that most of my adult life would be in elected office. I did not predict that, but the commitment was there. And so I feel very fortunate that I'm able to do this, but it was quite unlikely. I have high school classmates who tell me, "We didn't know you were interested in politics." Well, it's not as though I was manifesting all of this in high school. I'm grateful that I went to college and protested the Vietnam war because that certainly was a broadening experience for me.

Hirono is sworn into the U.S. Senate by then-Vice President Joe Biden in the Old Senate Chamber at the U.S. Capitol on January 3, 2013.

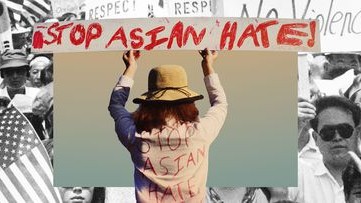

MC: With the surge in hate crimes against the AAPI community, do you feel a weight of responsibility, perhaps a great deal more than some of your other Senate colleagues, to work towards a solution?

MH: I definitely have a connectedness with the AAPIs who are being randomly targeted for these kinds of attacks. But my expectation is that everyone should, regardless of whether you share our racial backgrounds, be totally concerned about these kinds of attacks on any group. What I don't understand is why more people are not speaking up, particularly on the Republican side. But yes, I feel a connectedness, which leads to a sense of a responsibility to speak up, to add my voice to all of the other AAPI voices that are speaking up. I have never seen so many AAPIs on TV as I am now, which is a good thing.

MC: A major theme you write about is anger and what it means for women to be angry. Had you "gotten angrier" earlier on in your career [before the Trump administration], do you think you would have built the same reputation you have today?

MH: I have always considered myself a fighter, it's just that I haven't had to be so vocal about it. I can be very terse with people, so I did have a reputation in the legislature as the "Ice Queen" because I would just say to my colleagues, "Step aside, I'm doing this." But I wasn't very noisy about it. And that's why I have to laugh when people say, "Well, she's found her voice." I always had a voice. I generate a lot of angry reactions to what I say, but it doesn't particularly bother me because I'm going to keep on saying it. I think it's important at this time for people to know that there are people in elected office who are fighting for them.

I have to laugh when people say, 'Well, she's found her voice.' I always had a voice.

MC: In the book, you discuss how Dr. Christine Blasey Ford reached out to you while she was on vacation in Hawaii after the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearings. I’m glad you included this moment because I, like many other American women, often think about her and wonder how she’s doing. That anecdote gave me some solace.

MH: Yes. She told me she was okay. I was very surprised because she said she wanted to see me to thank me. I said, "I'm thanking you. We're all thanking you for your courage" in spite of all of the negative things said about her. It was really terrible what happened to her in that whole process, but that's what she points out. We have a ways to go.

MC: Right. And the fact that she remembered that you had made eye contact with her during the hearings is powerful.

MH: Because that's the kind of person she is. She wants to connect. And she sought to connect with every single member of that committee, and that's not something that Kavanaugh did, by the way. The contrast between the two was just so obvious. And the thing is that people were riveted all over the world with the Kavanaugh hearings. I describe [in the book] how my friends in Europe were watching. They didn't leave their hotel rooms. They were glued to the TV. There were a lot of people watching what America was going to do in that situation.

Senator Hirono questions Brett Kavanaugh during the second day of his Supreme Court confirmation hearing on September 5, 2018 in Washington, D.C.

MC: Immigration reform is important to you, along with education and labor. Do you have any specific goals or policies you want to accomplish by the end of your career?

MH: One of the first things I want to do is help Joe Biden get this pandemic under control and get our economy back on track, which means pushing really hard for the infrastructure bill that will create jobs and long-lasting benefits, along with addressing climate change and doing something about the racism in our country. These are huge areas of concern. I say to my staff all the time that people in our country are getting screwed every second, minute, and hour of the day, and if by our efforts we can decrease that number, we will be making a difference. We will be doing our jobs.

MC: You talk a lot about your mother's legacy. What do you want your legacy to be?

MH: I'm not looking for some huge legacy project or anything like that because I also understand that all of the battles that we thought we had won for a woman's rights to choose, for voting rights, these battles don't stay won. Eternal vigilance is required of all of us. I hope that people who read this book will be encouraged to speak up and to show up—not just physically, but emotionally. Half the battle is showing up. We can all speak up against racism. We can speak up for equality. And I think that fighting spirit, the "heart of fire" is in all of us. I hope that my book and what I do [in my everyday life] will encourage people that they can also be on this journey. All people have stories to tell of the challenges they face. If that leads us to be much more compassionate and accepting of others, that will be all to the good.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Related Story

Related Story

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.

-

The Royal Family Easter Rule Kate Middleton Broke in 2018

The Royal Family Easter Rule Kate Middleton Broke in 2018The Princess of Wales was pregnant with her third child—Prince Louis—at the time.

By Amy Mackelden

-

Tracee Ellis Ross Reflects on "Grief" Over Not Marrying or Having Kids

Tracee Ellis Ross Reflects on "Grief" Over Not Marrying or Having Kids"I grieve the things that I thought would be and that are not."

By Amy Mackelden

-

A "No-Fly Zone" Has Been Placed Over King Charles's Home

A "No-Fly Zone" Has Been Placed Over King Charles's Home"It prompted a security scare."

By Amy Mackelden

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan

-

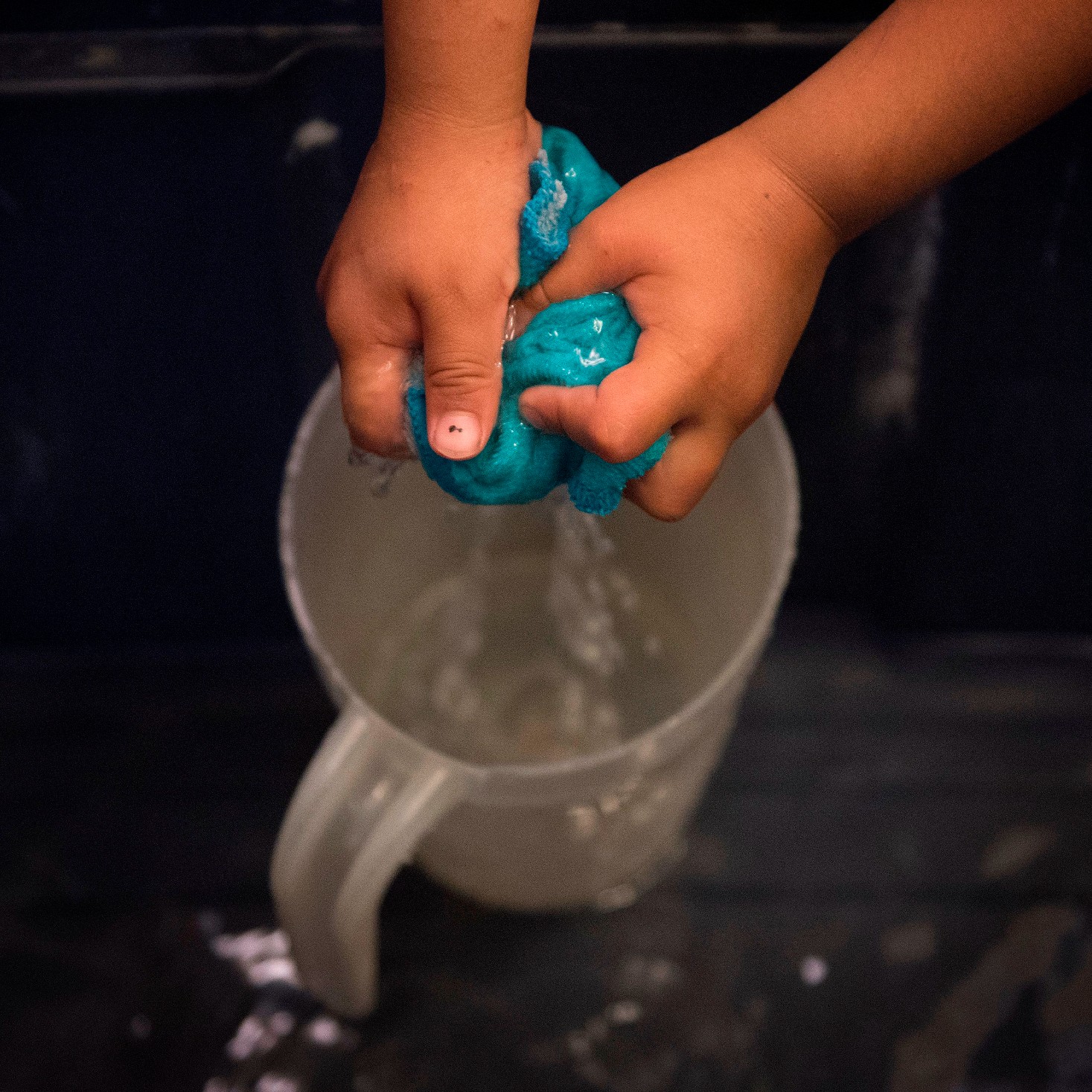

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein