Forced Sterilizations Are America's Best-Kept Secret

In 'Belly of the Beast,' director Erika Cohn documents the reproductive coercion that has occurred in California and throughout the country.

Over the past decade, award-winning director Erika Cohn has investigated a horrific abuse that's one of America's best-kept secrets: forced sterilization. The procedure, considered a form of modern-day eugenics that's historically been associated with Nazi Germany and the Holocaust, removes a person's reproductive organs as a form of birth control—without their consent. In her new documentary, Belly of the Beast, Cohn's reporting takes viewers inside California women's prisons, where women of color have claimed they were sterilized under false pretenses, misinformed by the doctors and hospitals they were sent to about what was truly going on inside their bodies, and left without choices to preserve their motherhood.

The main subject of the documentary, Kelli Dillon, then a prisoner at the Central California Women's Facility (the largest female correctional facility in the U.S.), filed a lawsuit against the doctor the prison referred her to for what she describes in the film as a "non-consensual, unlawful sterilization" that occurred in 2001 when she was a 24-year-old inmate. Though the court did not find the defendant liable after a jury trial, Dillon didn't give up. In 2014, she testified about her experience in front of the California state legislature, which helped lead to the passage of a law combating the "overly aggressive use of hysterectomies in prison," as the bill's sponsor, State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson, put it. The legislation bans any sterilization of an inmate for the purpose of birth control and adds protections for the prisoners, including the right to get a second medical opinion.

The shocking practice isn't being inflicted only on American prisoners. In September, a whistleblower filed a complaint alleging that forced sterilizations are being performed on immigrant women at the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's (ICE) Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia. The news exposed for many the long, unspoken history of forced sterilizations here in the United States. Hundreds of members of Congress are calling for a federal investigation into the matter as the battle for reproductive justice in our country continues.

"We had no idea that the news of the ICE sterilizations would also coincide with our film's release. It just demonstrates how the legacy of white supremacy in this country is manifesting itself in so many different ways," Cohn tells Marie Claire. "I'm grateful that the film can be used as a tool to mobilize during this moment. It's crucial that we don't view this as an isolated incident."

Here, Cohn discusses what it was like working on Belly of the Beast, why this was the hardest film she'll ever make, and what's still missing from the national conversation on forced sterilizations.

Marie Claire: When did you first learn about the forced sterilizations in the U.S., and what inspired you to raise awareness about them in Belly of the Beast?

Erika Cohn: I was first introduced to attorney Cynthia Chandler, who's one of the protagonists in the film, in 2010 through a mutual friend. I was really inspired by Cynthia's compassionate release work—she was the first attorney in California to get someone out of prison through compassionate release. I was also inspired by Justice Now's "Let Our Families Have a Future" campaign, which exposed the multiple ways that prisons destroy the basic fundamental human right to family—one of the most heinous being illegal sterilizations, which were primarily targeting women of color. To me, that screamed eugenics. As a Jewish woman, the phrase "never again" was always profoundly in the back of my mind. When I learned about this different kind of genocide that was happening through imprisonment, I knew that I wanted to get involved. Initially, Cynthia invited me into the organization as a volunteer. After that, I became a volunteer legal advocate, providing direct service needs for over 150 people in California's women's prisons. From there, I began collaborating with people inside on a project that ultimately became Belly of the Beast.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: How did you decide to focus on the story of Kelli Dillon at the Central California Women's Facility?

EC: When I started this project, the idea was to document the incredible activism that was happening inside California's women's prisons. Justice Now was the only organization in the country that had board members who are incarcerated informing policy and strategy from the inside out. That process was important to chronicle, and Kelli Dillon was at the center of that. I didn't have a chance to meet Kelli until a few years into the process. When I met her in 2012, she was working as a community interventionist in Los Angeles doing domestic violence prevention and gang intervention work. This was really a moment when she had put the sterilization issue aside and was focusing on building her career and serving her community.

She initially got involved in the film as an advisor behind the scenes. Once the Center for Investigative Reporting articles were released, there was this tremendous amount of momentum that ultimately led to a series of hearings in the California legislature and, ultimately, a bill was passed. That was the moment that Kelli and I decided that it was time for her to be on camera. As we reveal in the film, her discoveries catalyzed Justice Now to begin investigating the illegal sterilizations in prison. Through that, we meet the other survivors. So, if it hadn't been for Kelli, none of this would have ever come to light.

Attorney Cynthia Chandler (left) with Kelli Dillion (right) during a hearing for her forced sterilization case.

MC: A moment that stood out to me is when Kelli’s case was struck down in court and she essentially said, "As a Black woman, you’re telling me my life doesn’t matter. It doesn’t mean sh*t." There are a lot of Black women out there who are feeling this way right now, for so many different reasons. What was it like hearing her say that?

EC: There are multiple angles there for me. There's the friend side of this, and then there's the filmmaking side of this. It's so important that we understand that it's not just Kelli's story. This is something that women of color experience in the free world today. As a friend, you deeply feel and go through the process of supporting someone through all the ups and downs in friendship. From a filmmaking perspective, it was important to acknowledge that this happens to women of color, specifically Black women, in the free world as well.

Until we account for our eugenics practices and provide justice for the survivors and ensure safeguards to prevent future abuses, this will continue to happen.

MC: In the documentary, Cynthia Chandler discusses the emotional toll this work takes on her. Behind the scenes, what was it like for you, mentally and emotionally, to document this abuse over the course of almost a decade?

EC: This was probably the hardest film that I will ever make. It's incredibly difficult to uncover abuses of power and state-sponsored violence within these institutions because of the level of secrecy and privacy that they hide behind. It took years and years and years to be able to have the statistics that you see in the film. Fourteen-hundred people in California's women's prisons were sterilized between 1997 and 2013. From our reporting, we know that at least eight other states have or allow for sterilization procedures in certain circumstances. We don't know to what degree, but we do know that, from working and speaking with other organizations that provide direct service needs for people in women's prisons, it is happening.

In terms of me, personally, I was deeply embedded in the movement both as a filmmaker and as a volunteer legal advocate. Even though [we], as independent filmmakers, often feel siloed in our work, this was never a siloed effort. This was always in tandem with Cynthia and Kelli and the entire organization at Justice Now. I'm grateful that this was very much a collaboration. That collaboration is what kept all of us going.

MC: It was disturbing to hear the anonymous nurse justify the actions that occurred in the California Women's Facility. Before you started interviewing her, did you know she held these views?

EC: I did not. I wanted people to have the experience that I did in speaking with her and interviewing her because this is a very nuanced, complicated issue that is full of contradictions from the perspectives of many people. I felt like she really exemplified that. The experience that the audience has in hearing from her was very much the experience that I had in interviewing her. I think it's so important that we don't identify just one bad actor, one bad apple. This is so systemic. In the film, you see all of the different parties who are involved in order for one procedure to happen.

It's also important to acknowledge that we're not just witnessing eugenics through the sterilization abuse. We're witnessing systemic racism and population control through policing, through imprisonment itself, the immigration detention system, and through a lack of access to healthcare during the pandemic. It's important to note that imprisonment destroys the basic human right to family. When you lock up people throughout their reproductive capacity years or with exceedingly-long sentences, imprisonment itself is a form of sterilization. You are thereby preventing someone from being able to have children by locking them up. We saw that very recently when the Kenosha sheriff talked about using prisons as a form of preventing men from being able to have children.

I find it very fascinating that, in light of the recent discovery of the ICE sterilizations in Georgia's detention facilities, no one asked Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett if she would overturn 'Buck v. Bell'.

MC: Cynthia calls out the need to cover this abuse on a national level. The topic has gotten nationwide attention since the allegations of forced sterilizations in Georgia last month. What’s still missing from these conversations?

EC: When the news about the sterilizations in ICE detention facilities came out, the complaints were so eerily similar to the illegal sterilizations that we uncovered in our film. I mean, literally some of the accounts are almost verbatim. Because there has not been accountability for the sterilizations that have been performed, both historically and in recent times, modern-day sterilizations like what you see in California's women's prisons or in ICE detention facilities will continue to happen. The legacy of forced sterilization in the United States is not talked about. Right now, we have a petition on our website where people can pledge their support for reparations for California's forced sterilization survivors. I believe that will not only continue to make amends for the historical sterilizations, following in the footsteps of North Carolina and Virginia, but also ensure accountability for modern-day instances of sterilization.

Until we account for our eugenics practices and provide justice for the survivors and ensure safeguards to prevent future abuses, this will continue to happen. We're coming up on the 100-year anniversary of the infamous 1927 Supreme Court case, Buck v. Bell, which upheld a statute instituting compulsory sterilization for the "unfit" for the protection and health of the state. It set a precedent for states to legally sterilize people in prisons. While state, federal, and international law explicitly ban the illegal sterilizations, this particular decision has yet to be overturned. I find it very fascinating that, in light of the recent discovery of the ICE sterilizations in Georgia's detention facilities, no one asked Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett if she would overturn Buck v. Bell.

Belly of the Beast director Erika Cohn on set of the documentary.

MC: For anybody who’s working in a prison, detention center, or, frankly, in an OBGYN office and who notices red flags, what are next steps they should take?

EC: Because prisons and detention centers are such retaliatory environments, the courage of the [Georgia] whistleblower, Dawn Wooten, is something that should be acknowledged and commended. Not everyone who uncovers these abuses has the courage to come forward like she did. I believe there needs to be training for medical doctors and staff so that we don't reinforce racist ideologies in coercive environments. It's important to note in the context of the sterilizations that happened in California's women's prisons, that these sterilization procedures did not occur at the prisons themselves. They occurred in outside hospitals. The level of education that needs to happen within medical institutions is urgent and essential to being able to prevent these abuses from happening.

MC: What would you tell the survivors of these forced sterilizations?

EC: As a result of the film coming out, we've already seen a lot of survivors come forward who this happened to not only in California, but in other states and other kinds of institutions—historically and contemporarily. There are a lot of legal barriers that prevent these cases from ever seeing justice. Kelli said something in one of our panels from our opening weekend that I thought was really profound. She said, "I want you to know that you are not alone. Do not be ashamed. It was not your fault this happened to you. Just know that you can take your power back. There's life, there's love, and there's family on the other side of this."

Belly of the Beast is currently available to stream here and will premiere on PBS on November 23, 2020 at 10 p.m. EST. If you want to help put an end to forced sterilizations, you can donate to the California Coalition for Women Prisoners and California Latinas for Reproductive Justice. You can also visit the Belly of the Beast website for additional resources.

RELATED STORIES

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.

-

James Middleton Shares Why He Was "Breathless and Flustered" During Meeting With Queen Elizabeth

James Middleton Shares Why He Was "Breathless and Flustered" During Meeting With Queen Elizabeth"I heard a snort of laughter and looked past the Queen to see everyone in the room stifling their giggles."

By Kristin Contino

-

This Modern Princess Will Break a 600-Year-Old Tradition When She Takes the Throne

This Modern Princess Will Break a 600-Year-Old Tradition When She Takes the ThronePrincess Ingrid Alexandra of Norway will follow in a long-ago ruler's footsteps.

By Kristin Contino

-

Hailey Bieber's "Favorite Jacket" Is Actually One She Designed

Hailey Bieber's "Favorite Jacket" Is Actually One She DesignedIt's a piece for husband Justin Bieber's new brand.

By Halie LeSavage

-

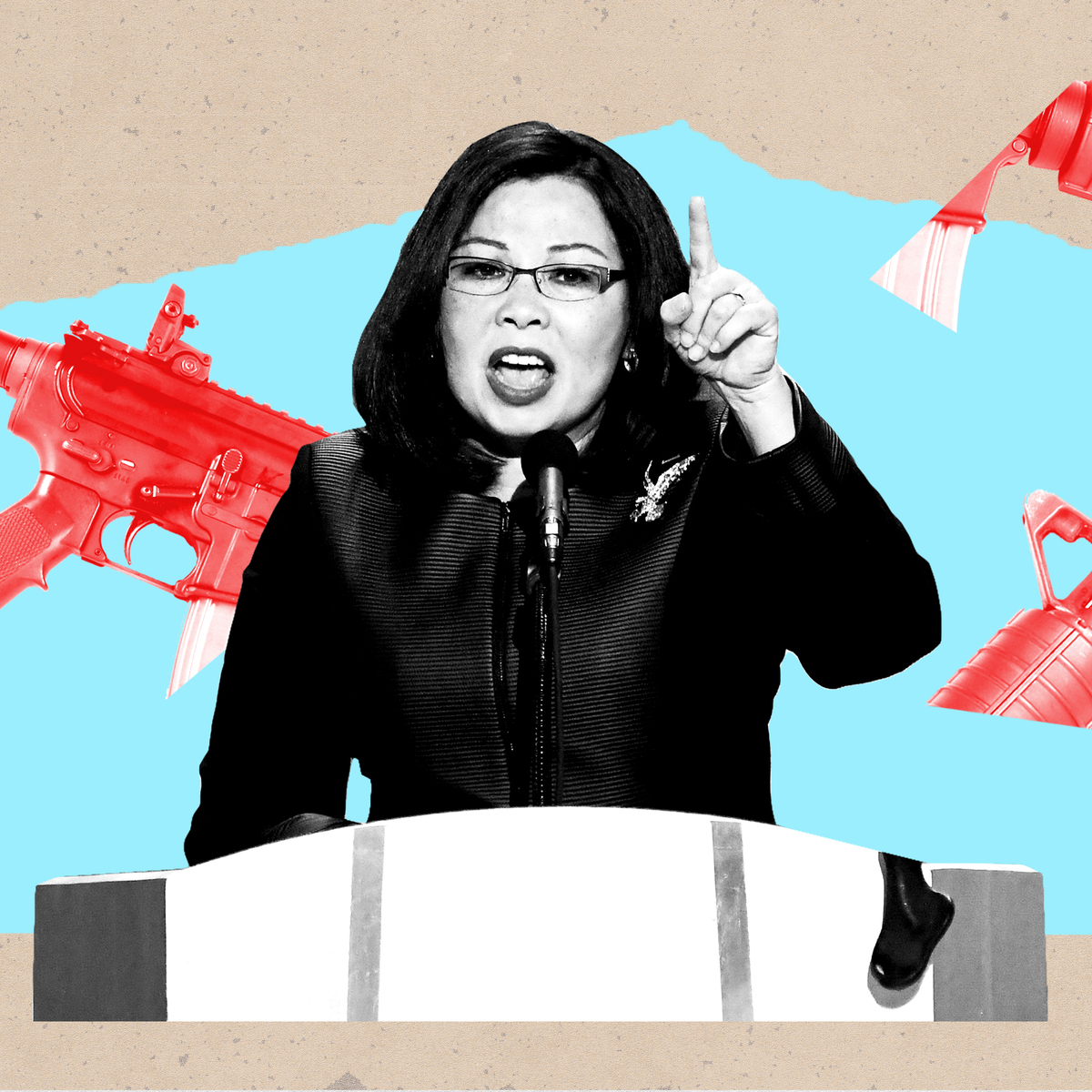

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

This Bill Wants to Stop Anti-Abortion Groups From Getting Your Private Data. Period

This Bill Wants to Stop Anti-Abortion Groups From Getting Your Private Data. PeriodPost-Roe period tracking apps and search history suddenly have serious implications.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Post-Roe, Pregnant People Will Become Suspects

Post-Roe, Pregnant People Will Become Suspects\201cWe anticipate a very dramatic increase in the rate of criminalization of all pregnancy outcomes.\201d

By Lorena O'Neil

-

As a Pregnant Woman Post-Roe, I'm Terrified to Travel in America

As a Pregnant Woman Post-Roe, I'm Terrified to Travel in AmericaOne author wonders: If my pregnancy turns tragic in a trigger ban state, will I get the life-saving care I need?

By Jo Piazza

-

Current Gun Control Policies Are Ableist

Current Gun Control Policies Are Ableist"Solutions" like active shooter drills and arming more people put the rights of gun owners above the rights of America's most vulnerable, including disabled people like myself.

By Heather Tomko

-

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do Next

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do NextBetween the U.S. occupation and the Taliban, supporting resettlement for Afghan women and vulnerable individuals is long overdue.

By Rona Akbari

-

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need Aid

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need AidHow To With the situation rapidly evolving, organizations are desperate for help.

By Katherine J. Igoe

-

Kristin Urquiza Wants Her Dad's Death to Mean Something

Kristin Urquiza Wants Her Dad's Death to Mean SomethingUrquiza's nonprofit, Marked By COVID, continues to demand answers and challenge our country's response to grief.

By Rachel Epstein