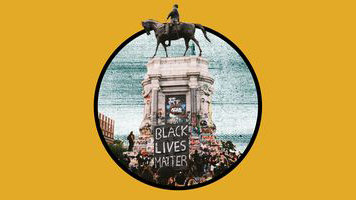

The Untold Story of the Black Women Fighting to Remove Racist Statues

Black women at forefront of the movement are being erased from the conversation in favor of white celebrities.

There has been a reckoning happening in the South that has intensified in response to the recent deaths of people of color including George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery: Statues of Confederate generals and members of the Ku Klux Klan are being protested against and torn down; Confederate flags are being withdrawn from state buildings; streets and schools are being renamed; country music artists have removed "Antebellum" and "Dixie" from their names.

Movements like these are gaining national attention thanks to celebrities like Faith Hill and Hayley Williams, who took to Twitter in late June to call for the removal of the Confederate iconography from the Mississippi state flag—a day later, state legislators voted to change it. A few weeks prior, Taylor Swift took to social media to call for the Tennessee Capitol Commission and the Tennessee Historical Commission to permanently remove the statues of Edward Carmack and Nathan Bedford Forrest from the Tennessee state capitol building. (Carmack was an elected official and editor of several newspapers in which he promoted racist rhetoric; Bedford Forrest was a slave trader, Confederate general, and first grand wizard of the KKK.)

Swift's Twitter thread shone a spotlight on the ongoing efforts, but there was one thing the message to her 86 million+ followers was missing: She didn’t acknowledge the work that Black activists have been doing for years to remove the racist symbols that sit in parks and state buildings and public arenas. The singer did not acknowledge the efforts already made by Black women, like Memphis natives Tamara "Tami" Sawyer and Jeneisha Harris. Consider Memphian Maxine Smith, who actively called for the removal of the Bedford Forrest statue in the 1980s. Or Zyahna Bryant, who started a petition in 2016 for the removal of the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia. And Bree Newsome Bass, who climbed up the South Carolina State House's flagpole in 2015 to remove the Confederate flag.

But Sawyer—who currently serves as a Shelby County Commissioner—is familiar with white authority figures taking credit for the groundwork she and others have been doing to remove racist emblems. Sawyer references the Take 'Em Down movement in New Orleans, which successfully got four statues in the city removed, but didn't receive proper credit. (Take 'Em Down NOLA also inspired movements in Dallas, St. Louis, Jacksonville, and Richmond, as well as Take 'Em Down 901, which Sawyer started.)

"Mitch Landrieu [then-mayor of New Orleans] got the credit, as a white man, for the work of Black grassroots organizers. I remember being upset because I was familiar with the work of Take 'Em Down NOLA," says Sawyer. Mayor Landrieu later published a book, In the Shadow of Statues, about getting the monuments torn down. Michael "Quess" Moore, a lead organizer for Take 'Em Down NOLA, confronted the former mayor for allegedly co-opting the group's work to sell his book. In a statement to Marie Claire, Landrieu rejected that notion. "Getting these monuments down took generations of leaders and work from countless individuals and organizations," he wrote. "It was a complete team effort and one which will have to continue together as the fight for justice remains crucial for the future of our country."

Sawyer is aware that she may never got proper recognition for her work, but that doesn't deter her. When the Cleveland police officers who killed Tamir Rice were not found guilty in December 2015, Sawyer held a prayer circle around the Nathan Bedford Forrest statue. "I used that as symbolism to talk about the systemic racism in our own city," she says. And later, when Sawyer introduced the activist Angela Davis during an event at the University of Memphis, she used the platform to bring up the statues: "I told her, 'Welcome to Memphis where the statues of Confederate slavers, who killed and abused Black bodies stand, yet Black workers today still don't make a living wage.'"

We, again, were criminalized as problematic, from [our] own city hall.

In 2017, Sawyer wanted to take her efforts to the next level. She was burned out by repeatedly seeing and hearing about Black men and women dying at the hands of cops. She went to a conference, and someone asked her what one thing she thought she could change. She jokingly responded, "I would like to remove these damn statues." When she returned home, she logged into Facebook and asked her social network who would want to meet about taking the statues down. Around 350 people came to the open forum at Bruce Elementary School, the first elementary school in Memphis to be integrated back in 1961. Sawyer's group collected 5,000 signatures for a petition, and wrote letters to the mayor and the governor. The petition and letter-writing campaign turned into an eight-day solidarity protest that started the night Heather Heyer was killed in Charlottesville, Virginia, during the protest of the "Unite the Right" rally.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sawyer sent the petition and letters to Mayor Jim Strickland. He denied receiving the documents at the time, so she decided to hand deliver them. Sawyer and her group were met at the front door by two police officers. "They wouldn't let me in, they wouldn't let the media in, and they wouldn't let anybody who was with me go in. We, again, were criminalized as problematic from [our] own city hall," she recalls. From there she made the six-hour drive to Albany, Tennessee, to testify before the Tennessee Historical Commission about the removal of the statues. She and the Take 'Em Down 901 organizers drove back to Memphis the same day to host a "die-in" during the a Memphis Grizzlies basketball game at the FedExForum. "We laid on the ground in the middle of people trying to walk into the stadium, and they got sheriff deputies out there," she says.

But even after her testimony and protests, the commission denied the removal. Then, on December 20, 2017, Sawyer received an unexpected phone call from City Hall: a private organization had bought the park and issued a unanimous resolution to remove the Confederate monuments. "This was an idea that we floated a couple of times. [We] had picked an organization that was ready to buy the park to remove the statues," Sawyer says, "but they'll tell you they didn't get any ideas from us."

Sawyer's journey shows the intrinsic issue with celebrity armchair activism: It's easy to safely tweet from home without acknowledging those who are on the ground and in the streets. "It's all well, good, and great that Taylor [Swift] is lending her voice to that. I don't want to take that away, but it's hurtful because it speaks to what it means to be a Black woman organizer," says Sawyer. "I've been doing anti-Confederate work since I was 16, and she tweets two or three things, and she's the queen of change."

Challenging the status quo as a Black person means having your life threatened by police, city officials, and racists—on and offline. It means being dragged, arrested, and banned from public and private spaces. It means finding funds for bail, lawyers, and security. "It would have been a little bit more authentic if, especially being from Tennessee, at a minimum, [Taylor Swift] had lifted Jeneisha Harris, who was just arrested," Sawyer adds.

Harris, a 23-year-old senior at Tennessee State University in Nashville, and her colleague Justin Jones were charged on June 4 with aggravated rioting (a felony) for standing on top of a police car. (According to Harris' tweets, a SWAT team was sent to her house.) Later that day, the Nashville Metro Police rescinded the arrest warrants.

Harris recalls participating in her first protest more than a year-and-a-half ago, held in Memphis and led by Sawyer. "I was like, This is it. This is the work that I have been looking for," she said of becoming an activist. When she returned to Nashville, she organized a series of protests during Black History Month 2019. Some of those protests included bringing caskets to the steps of the Tennessee State capitol. "We basically wanted to honor the ancestors who built the capitol but are not recognized in the capitol. However, there are people like Nathan Bedford Forrest inside the capitol," she says. Her group has done sit-ins and hand-delivered letters to the governor for the removal of those symbols of racism.

The work that we do is often overlooked and overshadowed by white people.

Harris' activism caused her to be banned from the state capitol (until recently). Two months after she was arrested and banned, a group of majority-white women had a sleep-in at the government building. "Politicians brought [the group] snacks, offered them water and everything that they needed. I remember being in tears because when I was being arrested, they took me down to the bus where they hold protestors, and I was so hungry," she says. "I think that says a lot about how Black activists are targeted and violated through laws and politicians here in Tennessee.”

While Harris appreciates Swift using her platform to bring awareness, she has noticed the influence that white women, specifically rich white women, have when it comes to calling for change. "The work that we do is often overlooked and overshadowed," says Harris. She wants people to know that this is not a new issue. Black women have been doing this work for ages and will continue to do so until not one racist statue stands.

RELATED STORIES

Brittney Oliver is a career and lifestyle freelance writer and content strategist based in Nashville. Over the past six years, Brittney has built her platform Lemons 2 Lemonade to help young professionals turn career obstacles around. Her platform is known for it’s networking mixers which has brought over 5,000 professionals, entrepreneurs and creatives together to turn life’s lemons into lemonade in NYC, Nashville, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, and Atlanta. In 2019 Forbes listed her as one of "Nine Black Women Leaders Dedicated to Empowering Others." Brittney has a BA in Public Relations from Howard University. After living in NYC for seven years, Brittney returned to her home state Tennessee to grow Lemons 2 Lemonade nationally.

-

Netflix's 'North of North' Transports Viewers to the Arctic Circle—Meet the Cast of Inuit Indigenous Actors

Netflix's 'North of North' Transports Viewers to the Arctic Circle—Meet the Cast of Inuit Indigenous ActorsThe new comedy follows a modern Inuk woman determined to transform her life.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Princess Beatrice's Husband Pays a Rare Tribute to These Royal Family Members on Instagram

Princess Beatrice's Husband Pays a Rare Tribute to These Royal Family Members on InstagramEdoardo Mapelli Mozzi shared some behind-the-scenes snaps from the F1 Grand Prix in Bahrain.

By Kristin Contino

-

Allow Kathy Bates to Convince You to Grow Out Your Grays

Allow Kathy Bates to Convince You to Grow Out Your GraysOne look at her new style and you'll be canceling your root touch-up pronto.

By Ariel Baker

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

Her Love of Basketball Left Her Stateless

Her Love of Basketball Left Her StatelessOne athlete’s quest for freedom from Afghanistan, where the Taliban's restrictive and regressive policies on women's sports put her life in danger.

By Abigail Pesta

-

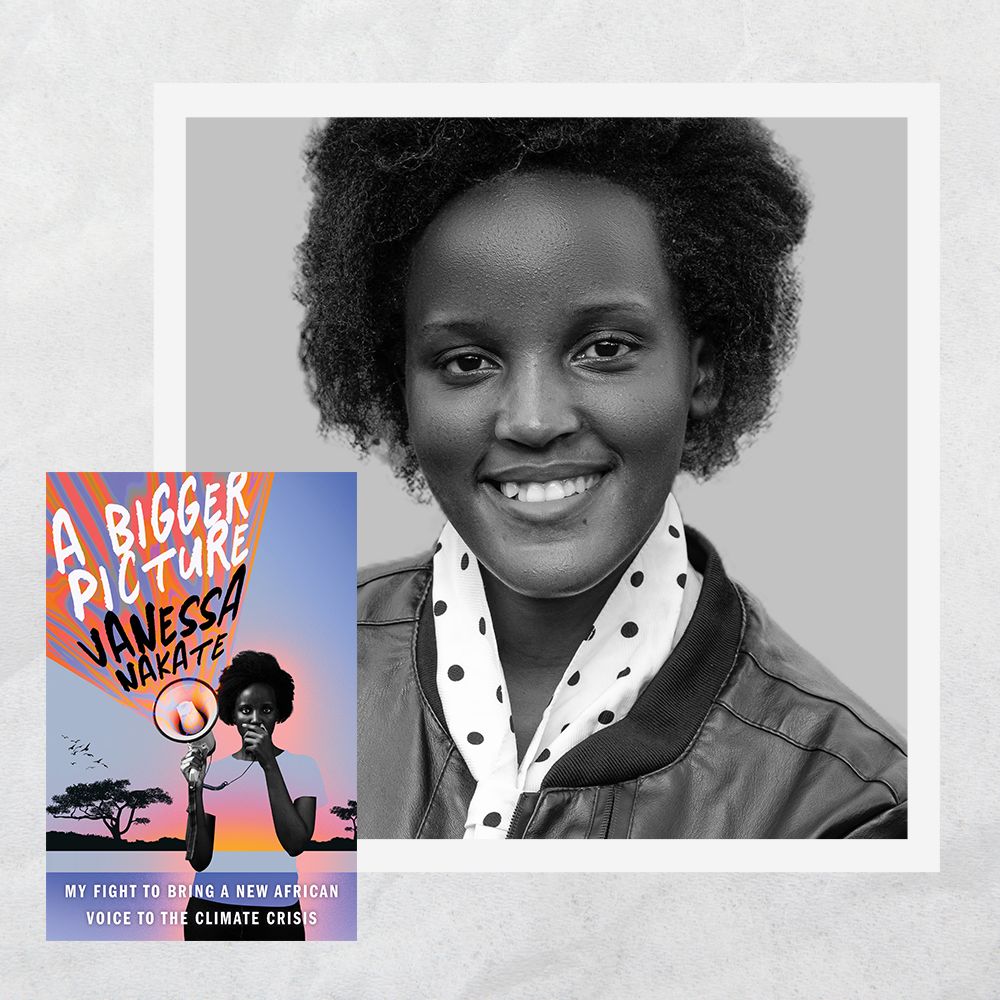

Education for Women and Girls Is Crucial for Climate Justice

Education for Women and Girls Is Crucial for Climate JusticeIn an excerpt from her new book, 'A Bigger Picture,' Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate discusses the impact educated African women and girls can have on solving the climate crisis.

By Vanessa Nakate

-

It’s Time to End Equal Pay Days and Pass the Equal Rights Amendment

It’s Time to End Equal Pay Days and Pass the Equal Rights AmendmentThe passage of the ERA is a chance for our country to prove it truly values women.

By Hala Ayala

-

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the Organization

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the OrganizationUnder Butler's leadership, the largest resource for women in politics aims to expand Black political power and become more accessible for candidates across the nation.

By Rachel Epstein

-

Anita Hill Believes We Can End Gender Violence

Anita Hill Believes We Can End Gender ViolenceThree decades after her landmark testimony in the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings, the esteemed professor and lawyer has a message for leaders: The time is now to prioritize anti-gender violence policies.

By Rachel Epstein

-

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State Legislators

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State LegislatorsEmily Cain, executive director of EMILY's List and and former Minority Leader in Maine, says that to stop the assault on reproductive rights, we need to start demanding more from our state legislatures.

By Emily Cain

-

Your Abortion Questions, Answered

Your Abortion Questions, AnsweredHere, MC debunks common abortion myths you may be increasingly hearing since Texas' near-total abortion ban went into effect.

By Rachel Epstein