The Guerrilla Feminists Papering Paris at Night

Frenchwomen have covered their cities with slogans denouncing violence against women. They refuse to stop until they see change.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

On a mild Tuesday night, a few hours before midnight, a dozen women assemble outside the Argentine métro stop in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, loaded down with a melange of tote bags, backpacks, and plastic buckets. They come from all directions but find and greet each other easily, and within minutes the process has started. Some pour powdered glue into buckets while others add water from bottles. The unluckiest in the group mix the cold slurry by hand. “Water in the fountains gets cut off in the winter,” Raphaëlle, a 27-year-old lawyer, tells me, so they make do with what they can, bringing water from home or running into bars to ask for a fill-up.

Nearly every night since August, in some part of the city, women have been gathering in groups of two or three to paste on public walls black-and-white slogans demanding that the French government act to prevent femicide—the murder of women by their current or ex-partners—as well as other acts of violence against women. Despite the government’s promises last year to enact change, the women believe that those promises are empty. “Homicides are going down in France, but femicides are going up,” Raphaëlle explains. In September 2019, Gérard Collombe, the minister of the interior, reported that incidents of violence against women had increased by 22 percent in 2018. By this night, only seven days into the New Year, there had already been four femicides. “7 Janvier: 4 feminicides,” reads one of the slogans. “I brought a number five just in case,” Raphaëlle says. “If we're not gluing that same day, we have to check to see that the number of murders is still up-to-date.” As of press time, the number is now 11.

The slogans vary, but the style is always the same. Black paint on white paper, pasted with the wheat glue mixture in long lines on public walls. A nos soeurs assassinées. To our murdered sisters. Nous sommes toutes des héroïnes. We are all heroines. On arrêtera de coller quand vous arrêtez de violer. We’ll stop pasting when you stop raping us. The group prefers to paste in hard-to-reach areas, like overpasses or high above windows—climbing on top of trash cans, scurrying up window ledges, or on rare occasions toting ladders under their arms—because their work is frequently torn down or defaced by the next day. When the slogans are defaced, the women simply return to the area and paste again.

Article continues belowBy this night, only seven days into the New Year, there had already been four femicides.

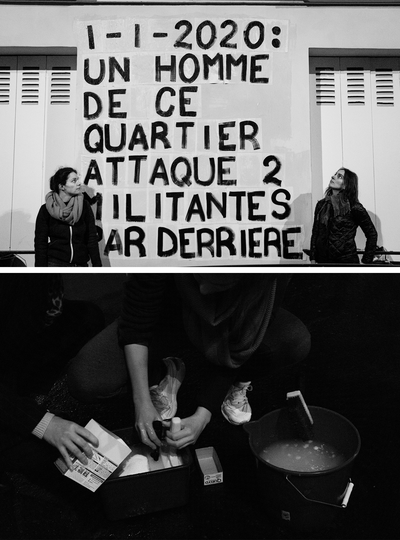

On this particular night, the women, collectively known as Les Colleuses, gather in a larger group than normal, some dressed in dark jeans and sweatshirts, others in their office clothes. They’re together this evening to paste a specific slogan intended for a very specific audience. A week prior, two of the women in the group were out pasting when a man in the neighborhood attacked them. On the base of a sculpture in the center of a prominent roundabout not far from the Arc de Triomphe, Les Colleuses worked quickly. “Ici un homme a frappé 2 colleuses:” Here, a man attacked two of us.

“That [violent response] is really new for us,” Camille, a 24-year-old Ph.D. student, explains. The man had approached Raphaëlle and another woman named Karma, shouting that the slogans were dirty and rude. The tactic when people engage is to be nice and attempt to inform, Raphaëlle says, but the man’s tone was very aggressive. So the women didn’t stop pasting and returned the same aggressive tone. The man attempted to kick and hit them until people on the street intervened. “That’s why we’re here tonight,” Camille adds. “He lives near here.” After the first slogan was affixed to the base of the sculpture, women split into smaller groups to paper as many nearby streets as they could. By morning, the man who had attacked them would wake up to see his neighborhood completely covered.

Above: Raphaëlle (left) and Karma tell the world what happened; Below: Les Colleuses get to work.

Raphaëlle, dressed in sweats, sneakers, and a scarf (the pasting can be a messy task), climbs onto a window ledge with a paintbrush in hand and a bucket of glue at her feet while her friend Pauline quickly hands her page after page. As she brushes glue over paper, patting each piece down with a hard thwack, a group of three men smoking cigarettes outside of a bar take notice. The men giddily shout out their best guesses for what the resulting message would be, a misbegotten game of Wheel of Fortune. Raphaëlle and Pauline complete the slogan, but the onlookers are no longer interested; they return to their conversation. 1% des violeurs condamnes, it reads. 1% of rapists are convicted.

People all over Europe are waking up to the guerrilla work of Les Colleuses. The movement, which was started by radical feminist Marguerite Stern in Marseille last August, has spread to more than 100 French cities, and as far as Belgium, Germany, Italy, the U.K., Portugal, and Luxembourg. There is even word that a slogan was discovered on a wall in Syria. There are more than 300 women participating in the group in Paris alone, organizing through WhatsApp and Facebook groups and on Instagram, and they display their work proudly through city-specific Instagram accounts, like @collages_feminicides_paris. The group’s structure is horizontal—there are no leaders by design—and tutorials on how to paste and what supplies to use are readily available through Les Colleuses’ various channels. The only requirement to take part is a belief that violence against women must be stopped.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

While there have been a few instances of women being fined or threatened by police, none of the Colleuses in France have been arrested yet. When people pass them on the street, they are met with either curiosity or anger. One landlady pokes her head out a window as Pauline and Raphaëlle work—she’s angry that they’re defacing the wall of her building. The pair explain the urgency of the slogans and why it’s important that they continue. The woman responds that she’d be taking it down tomorrow, and eventually shuts the window. “She said, ‘You know you're not allowed to do this’ and I'm like, ‘well, yes I know,’” Raphaëlle says. Pauline adds, firmly, “That’s the point.”

Les Colleuses in solidarity against gender-based violence.

“Before taking part in this movement, I was often afraid,” says a 29-year-old woman named Caro whom I follow as she pastes on a different night. “But seeing the collages and knowing there are so many women taking part in this revolution, I’m no longer afraid. It gives me strength every day.” She used to be ashamed of her experiences with abuse. “Now I know it’s the men who should be ashamed.” That night Caro walks down the center of a major Parisian highway, closed for construction, and scrambles up a ladder to plaster Plus ecoutées mortes que vivantes—“Heard more dead than alive”—on a wall that hundreds of cars would see the next morning.

“It’s very patriarchal thinking: these are our streets, our buildings, our laws. And you women, you are ours, too,” one of the Colleuses, who wished to remain anonymous, tells me. “But this—” she says, gesturing to the women putting up a collage that Tuesday night, one that told of their own experiences of abuse by the hands of a man in that very neighborhood, “—this is freedom. With this, we are free.”

Clarification: A previous version of this story stated that the movement has spread to 13 French provinces; it has spread to a mix of cities and French-held territories.

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.