Rohingya Women Aren't Just Refugees—They're Leaders

Rohingya women are getting political.

In June 2018, the Shalbagan refugee camp in Bangladesh, home to 41,000 Rohingya—the Muslim minority group that fled genocide in Myanmar—became the first of 30 new camps to elect leaders. When the results were tallied, organizers at the United Nations Refugee Agency and The Adventist Development and Relief Agency International, which spearheaded the vote, were pleasantly surprised to learn female refugees had won half of the 12 volunteer seats. “I’ve always been interested in helping out, so when I got the chance to run, I did,” says Rehana Akhter, 35, one of the newly elected members. “This has never happened before in our society!”

Gender parity in politics would be good news anywhere, but especially for Rohingya women, who along with their children make up 80 percent of the refugee population yet rarely held jobs or participated in community affairs back home. “Women didn’t lead back in Myanmar. Even if we’d wanted to, our society doesn’t allow for it,” Akhter says. “But in Bangladesh, the prime minister [Sheikh Hasina] is a woman, so we are seen differently here.”

The elections weren’t an easy win. Many men in the camps were outraged that women like Akhter were chosen as block leaders over them. “How can the women lead us when they have never taken charge of anything in their lives?” complains Abdus Salam, a former leader who wasn’t reelected. “Our women don’t do this kind of work.”

Block leader Romeda Begum inside a children’s learning center, where disabled children spend the day with various nonprofit organizations. Begum is responsible for making sure these programs are carried out everyday.

But the new female leaders are proving him and other men wrong—helping fellow refugees fill out paperwork and find shelter, ensuring aid is getting to intended recipients, managing water, hygiene, and sanitation issues, and even stepping into to mediate domestic disputes as needed. They also readied the camps for monsoon season; aid workers had feared the latest storms would be deadly, but the camps sustained minimal damage because they were so well-prepared. “Women are doing things they never did,” says Romeda Begum, a 27-year-old who arrived in October 2017, along with her mom, younger sister, and brother, and now serves as block leader.

The women also cracked down on men selling their family’s aid cards—used to get weekly food rations, like rice, oil, salt, onion, and other necessities—for yaba, a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine. “Before, the women were too shy to report what had happened,” Begum says. “[And even when they did], the men in charge wouldn’t help because they were friendly with their husbands and didn’t take the wives concerns seriously. I’m able to help with that.”

Block leader Romeda Begum attends a weekly training session on women’s safety with the Bangladesh National Woman Lawyers’ Association (BNWLA).

That was a life-saver for Noor Fatima, a 23-year-old woman who has lived in the camp with her husband and two children since September 2017. After her husband, a drug addict, sold their aid card to fuel his yaba addiction, she was barely getting by on the remaining lentils and rice she had, begging fellow refugees to share their own limited supplies while her hungry children cried. She tried to get her majhi, a male refugee leader appointed by the Bangladesh Army, to help, but he dismissed her concerns as a petty domestic dispute.

Frustrated, Fatima turned to Akhter, then fresh off her election victory, who was able to get Fatima’s aid card back—and help her file for divorce from her husband, something she had long been trying to achieve. “Rehana understood my problem and helped me get justice,” Fatima says. “I’m so glad there are women in charge now.”

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

A young Rohingya woman walks with her child in the Shalbagan refugee camp in Bangladesh.

Such accomplishments are why elections will now be held in all of the camps, where nearly one million refugees live, beginning this summer. More than anything, the women want to return to Myanmar, Akhter says, and if they are ever able to do so, they hope to bring their newfound power with them. “I want women to live the way we do here—much easier and free,” Akhter adds. “If God blesses us, Rohingya women can lead in Myanmar.”

This story was reported with a grant from the South Asian Journalists Association.

A version of this story originally appeared in the July 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

Jennifer Chowdhury is an independent journalist based in New York City and Bangladesh. She covers the South Asian and Muslim diaspora with a specific focus on gender rights. She is passionate about covering stories on women of color around the world whose voices are stifled by patriarchal attitudes, systematic racism and socioeconomic burdens.

-

Travis Kelce's Mom Reportedly "Liked" a Comment About His Future as a Dad

Travis Kelce's Mom Reportedly "Liked" a Comment About His Future as a Dad...and then removed it.

By Lia Beck

-

Prince Louis Will Soon Be Allowed a Special Privilege That Prince George and Princess Charlotte Already Have

Prince Louis Will Soon Be Allowed a Special Privilege That Prince George and Princess Charlotte Already HaveThe youngest Wales child will turn 7 on April 23.

By Kristin Contino

-

$20 and 30 Minutes Is All You Need for a Vacation-Level Glow

$20 and 30 Minutes Is All You Need for a Vacation-Level GlowSelf-tanner secrets, according to a beauty director.

By Hannah Baxter

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

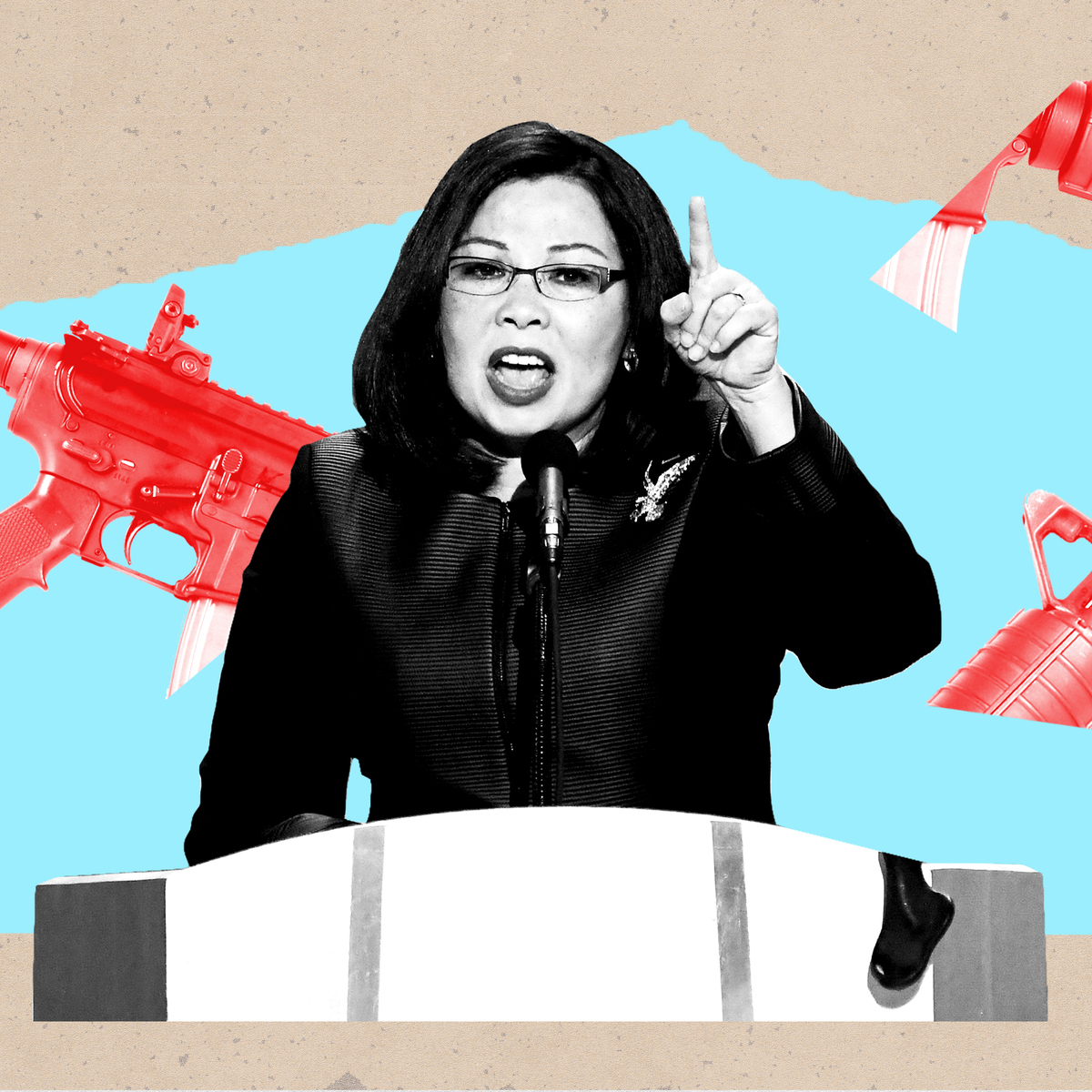

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan

-

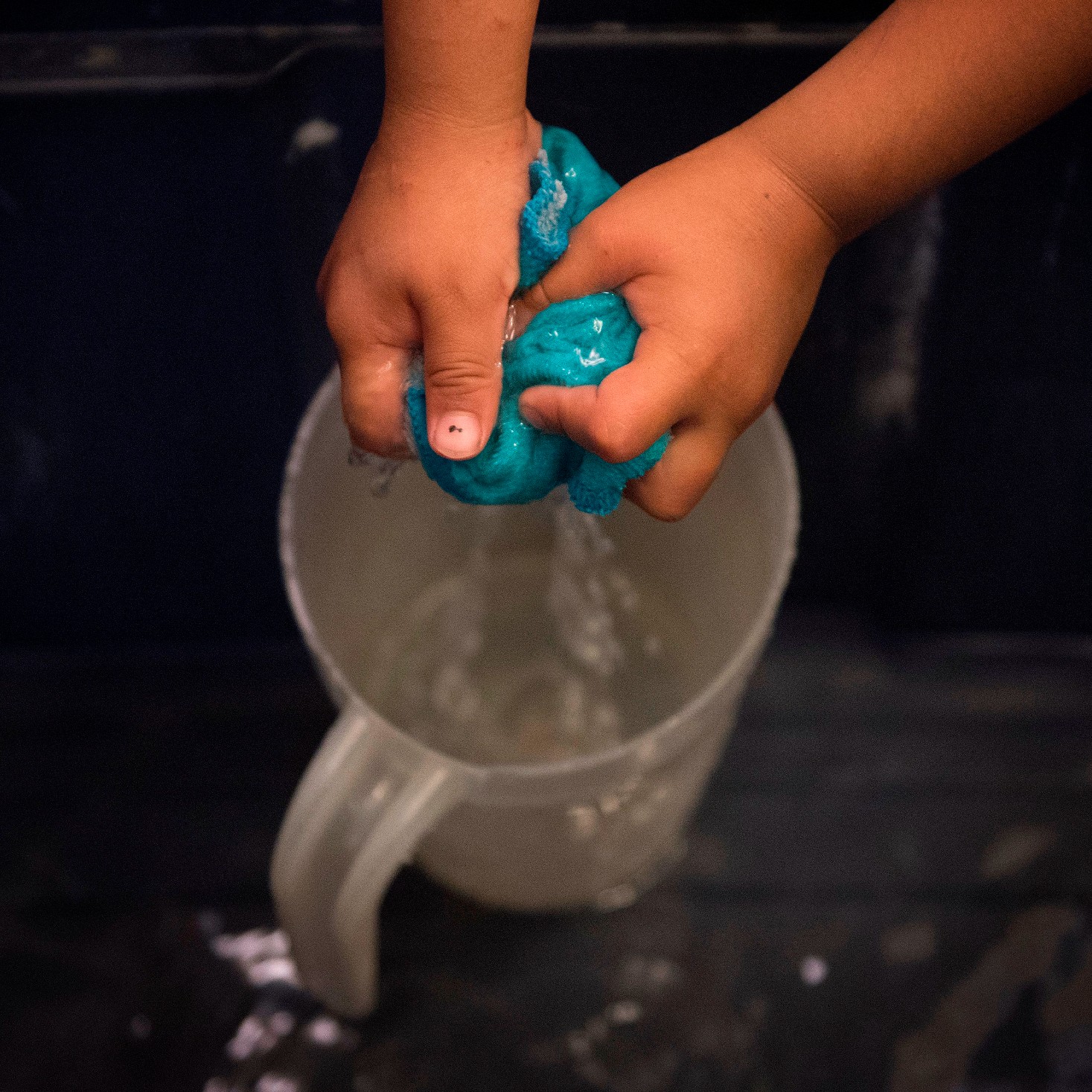

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein