When Your Spouse Is a Politician, What Happens to You?

Contributing editor Chloe Angyal, girlfriend of an Iowa state senator, explores her new role just this side of the spotlight.

The Iowa Capitol building is a gorgeous structure, topped with five golden domes, the largest of which contains a gold-ringed ceiling painted with a bright blue sky and crisp white clouds. Every Wednesday in the spring, in a small back room on the first floor, a group meets for lunch, toting trays from the cafeteria or goodies from home. On the walls hang decades worth of class photos of previous iterations of the group, the pictures getting grainier and the hair bigger as you go back in time.

Welcome to the Legislative Ladies League.

That’s no longer the official name of the group run by and for spouses of Iowa state representatives and senators. It was changed some time in the nineties to the LegisLative League, a tweak that nodded to gender equality while preserving the acronym. Still, I’ve yet to see a male spouse show up to a meeting.

That might be because I haven’t been to many, having just finished my first legislative session as a member of this small but welcoming club. In addition to being a new member, I’m also the youngest. And, as far as I know, the only one who isn’t yet married to the legislator whose election granted me admission.

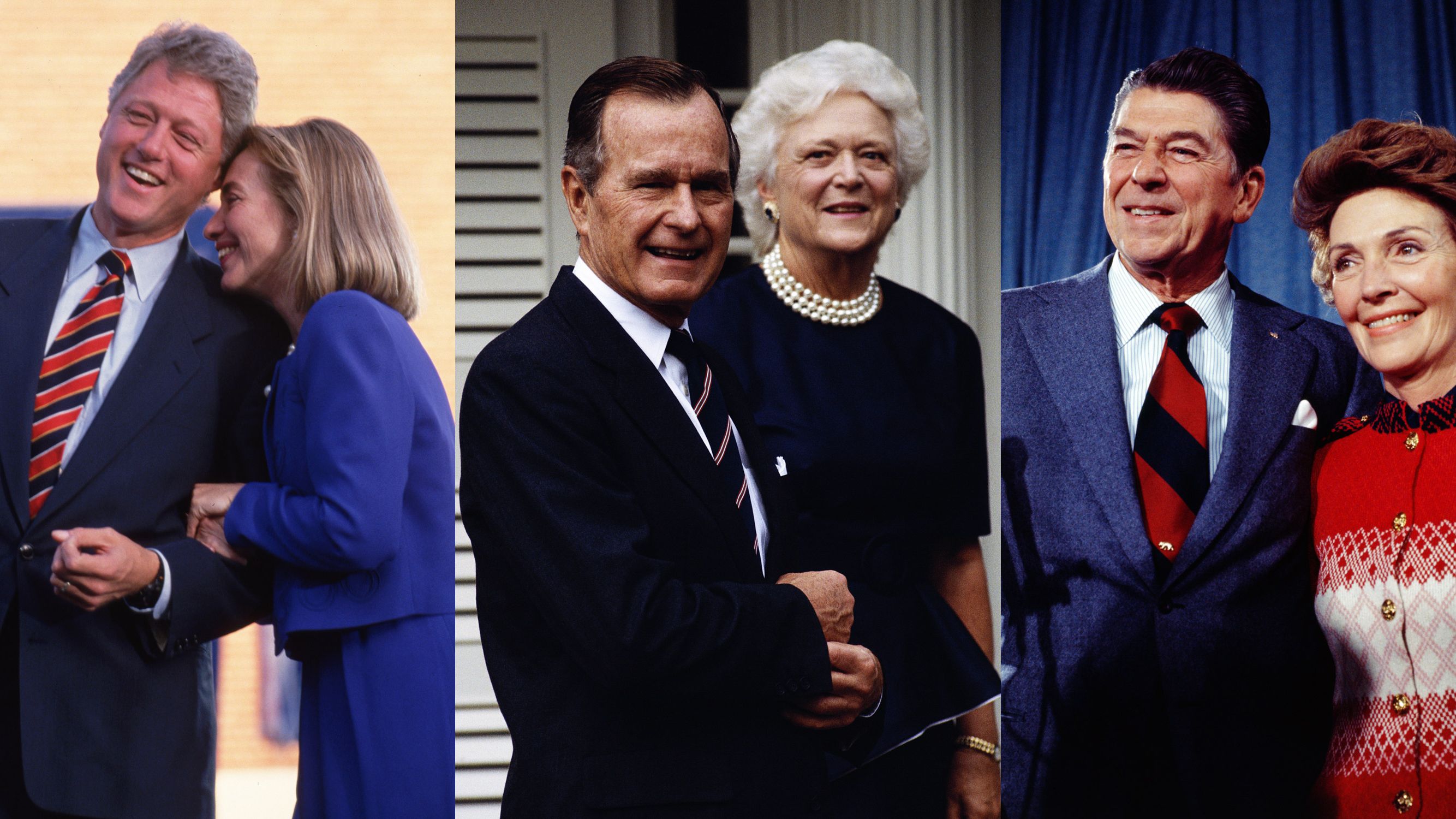

The phrase “political wife” evokes pitiable visions of a docile, helmet-haired woman standing silently behind her husband.

When I was a girl, I envisioned lots of future versions of myself: Broadway Dancer Chloe. French Translator Chloe. Political Wife Chloe never existed, even in my imagination. But here I am—a journalist, a teacher, and, as of last November, the girlfriend of an elected official.

The phrase “political wife” evokes pitiable visions of a docile, helmet-haired woman standing silently behind her besuited and gray-templed husband. She is smiling admiringly as he asks the public for more power, or frowning grimly as he admits to abusing it. She appears in campaign materials, where she affirms her husband’s heterosexuality and, if there are kids or a dog in the shot, his status as a steady and trustworthy family man. She is his hero.

Or, the phrase conjures nightmarish images of a ruthless, scheming Lady MacBeth, pulling the strings behind the scenes and usurping the power her husband came by honestly. (You can tell which one she is because she has shorter hair, and she’s probably wearing a pantsuit.)

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

But as the reality of what a legislator looks like evolves—as our representative bodies get less white, less male, and less straight—so too does our vision of a political spouse. Chasten Buttigieg, husband of presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, is “winning the 2020 spouse primary” with his relatable social media presence and his affectionate jokes at the expense of his spouse.

Chasten Glezman, right, husband of Presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, is breaking the mold of political spouse.

In the 2018 midterms, an unprecedented number of millennials ran for office: about 700, and a lot of them won. There are now 26 “snake people” in the House of Representatives, up from 5 in the previous session, making this Congress the youngest in a generation. And there are more women in Congress than ever before. For the first time in American history, a state legislature—Nevada’s—is majority women.

There has been lots of talk about how millennials might campaign and govern differently: They’re more likely to be Democrats, more likely to be progressive and meme-fluent, and more likely to care about things that millennials care about, like the climate crisis, student loan debt, and racial justice. There’s been less talk about how those candidates’ romantic partners will make sense of one of the most antiquated roles in American politics.

Of course, lots of people who currently occupy the role of “political wife” are not, in fact, wives. They are husbands, or boyfriends, or like me, girlfriends. But the words “political husband” or “political girlfriend” don’t roll off the tongue, in part because we’ve had so little practice saying them. Political wifery, as I’ve taken to calling it, technically knows no gender or marital status, but for generations, it’s been almost exclusively performed by married women.

Political wifery requires doing the things that have long been expected of women: that they shelve their own ambitions in the service of someone else’s.

And even as more women and gay men enter politics—bringing with them husbands, boyfriends, girlfriends, and wives—political wifery, no matter who’s doing it, is gendered work. It requires doing the things that have long been expected of women: that they be unfailingly supportive, and that they shelve their own ambitions in the service of someone else’s. That they show up, shore up, shut up. And smile.

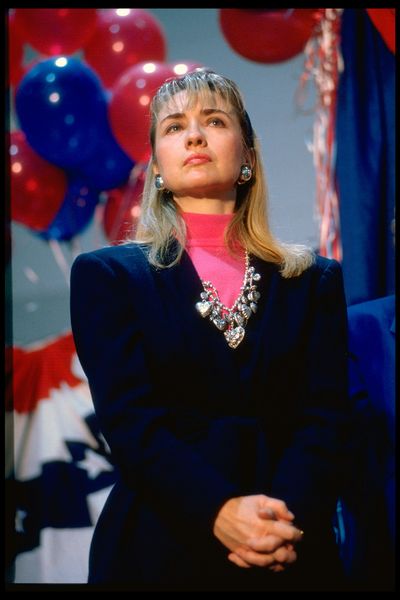

As is the case in many romantic partnerships, the political wife might also be the closest and most influential advisor his or her partner has. And soft power—the ability to humanize a candidate, or help them network and build goodwill with voters and fellow politicians—is real power. But when political wives get explicit about their strategic and political contributions to their husbands’ work...well, ask Hillary Clinton how well her 1993 health care reform efforts were received.

Hillary Clinton was often seen during her husband’s presidency as having more ambition than befits a political spouse.

When my partner decided to run for state senate, I did what any good Hermione Granger fan would do: I went looking for books that might help me understand what I was getting myself into. Unfortunately, unless their husbands are elected to the presidency, political wives don’t write books. Some senators, especially those eyeing presidential runs, write political memoirs, but their wives? We don’t hear a lot from them.

One exception is Connie Schultz, the Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist whose husband is U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio). Schultz’s book about being on the campaign trail when Brown first ran for the Senate in 2006 is aptly titled ...and His Lovely Wife.

I was especially eager to hear what Schultz had to say about her experience of political wifery because like her, I am an opinionated and outspoken feminist journalist partnered with a politician. My stomach clenched with anxiety when I read what she had to say about that kind of pairing.

“I don’t mean to suggest that a woman who is a feminist and a columnist accustomed to lugging around her own megaphone can’t fall in love with a congressman, and even marry him,” she wrote. “In fact, I’m living proof that that’s exactly what she can do, although an awful lot of people like to point out that we’re not your typical combo platter… I’m a wife paid to give her opinion, so I’m your basic nightmare as a political wife.”

It me, Chloe Angyal, feminist journalist and basic nightmare.

I’m happy to report that, so far, no one—not my partner, not his campaign manager, and not a single voter or constituent—has made me feel like a walking, talking liability. Still, there is something profoundly weird, and not a little scary, about being a professionally outspoken woman, and signing up for a role that might require you to be quiet and uncontroversial. What if I write (or have already written) something that will make it harder for my partner to do his job? What if I fail at being unfailingly supportive the way political wives are expected to be? What if my life, and my career, get swallowed by his?

Political wife and outspoken columnist Connie Schultz with her husband, Sherrod Brown, on election night in 2006.

It’s hard to get political spouses of any gender to talk to you on the record about their experiences. Believe me, I tried. I tried wives, I tried husbands, I tried to ask a young member of the House who’s single about her thoughts on the role of the millennial political partner. No one wanted to talk, even when I told them that I’m a political partner myself.

So, I called the one political spouse I knew would have no hesitation: Connie Schultz.

As it turns out, I’m not the only one to do that. Schultz fields calls from the wives of candidates and prospective candidates fairly regularly. When I ask her if men seek her wisdom, she says it’s pretty rare. “I don’t think men tend to worry about how they’re going to be perceived,” she mused. “They just keep doing what they do.”

Her advice to women is to be more like those men. She’s a vocal proponent of women in our shared position holding on to their own jobs and identities—even though some of her fellow political spouses were horrified by the idea of her continuing her journalism career after Brown entered the Senate (“my husband is my career,” one of the wives told her, without a hint of a joke).

Voters want to vote for real people who, if they’re partnered, are in reasonably equitable relationships with three-dimensional people.

But she doesn’t think voters actually care about that—in fact, she thinks women voters are totally cool with wives like her. “The average knowledgeable voter, particularly women, tend to respect women who’ve decided they’re going to have their own lives still while their husbands are doing this,” she says. Indeed, the voters of Ohio re-elected her husband in 2018, after choosing Trump by a margin of 8 points in 2016.

Where progress has been slower, she says, is among the political class. She has no patience for “the old school thinking of too many political reporters and consultants, still, who think it is their job to basically render us mute. Or incidental to it all, except when they need us to be on stage for something.”

The author and her partner, Iowa State Senator Zach Wahls (D-Coralville), during Wahls’ primary campaign in March 2018.

Schultz teaches journalism at Kent State, her alma mater, and her interactions with students make her optimistic about both the new wave of candidates, and the partners they bring with them. Among her male students, “there’s such a sense of partnership, even in their friendships,” she says, and it makes her hopeful that the new generation of electeds can reimagine what it means to be a political spouse.

She thinks that’s especially true in a moment when voters are hungry “for authenticity, for genuineness, for something that doesn’t feel practiced and rehearsed and focus-grouped.” They want to vote for real people who, if they’re partnered, are in reasonably equitable relationships with three-dimensional people.

Listening to Schultz, the knot in my stomach started to unwind a little. I’ll never be Broadway Dancer Chloe or French Translator Chloe, but I don’t have to be Political Wife Chloe, either—at least, not in the way we’re used to seeing.

This is only the start of millennials taking over American politics, from the local level all the way to Washington. I’ll keep my membership in the Iowa LegisLative League, but I’m also looking forward to building an informal nationwide league of millennial political partners of all genders and marital statuses. I want to pass on to them the precious advice that Schultz gave me: Be yourself, without apology.

“You’re who you are. He married you for a reason, and he wants you as his partner in this for a reason. And you don’t need to apologize for you are. He didn’t marry a prop, and if it’s a good marriage, it’s not that, you’re not a prop or a problem, you’re a partner. So feel free to be one.”

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

MORE ON THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN

Chloe Angyal is a journalist who lives in Iowa; she is the former Deputy Opinion Editor at HuffPost and a former Senior Editor at Feministing. She has written about politics and popular culture for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The Guardian, New York magazine, Reuters, and The New Republic. Angyal has a Ph.D. in Arts and Media from the University of New South Wales.