The Secret Evangelicals at Planned Parenthood

They may demonize the health clinic in public, but throngs of young Christian women are patronizing it in private for birth control, preventative care, and, yes, even abortions.

Elizabeth* is a 29-year-old stay-at-home mother of four. From a young age, her conservative evangelical parents and pastors impressed upon her the values of the religious right: that a woman's virginity is a gift to her husband, that sex outside of marriage is a sin, that abortion is murder.

Planned Parenthood was the enemy. "My dad instilled in me that we were against that group," Elizabeth says. "He was the kind of guy that would honk in support when people were outside protesting."

At 18, Elizabeth married her high school sweetheart in the same conservative California church she had attended every Sunday since childhood. But the marital bliss she'd been taught would follow didn't—within just a few years, Elizabeth discovered that her husband was having an affair, and she divorced him soon after. Suddenly she was uninsured.

Before long, Elizabeth started experiencing severe cramping and heavy periods—symptoms she would later learn were the result of an ovarian cyst. "That's when the whole Planned Parenthood thing started," she recalls.

Voices from the religious right have long been some of the loudest and most vitriolic critics of Planned Parenthood, an organization that provides reproductive health services to an estimated 2.5 million women and men in the United States each year. They've called Planned Parenthood a baby-killing factory and a bastion of evil. Evangelical Christians are the most visible aggressor in the fight to overturn Roe v Wade. And this is a social group with hefty political sway: 25 percent of Americans identify as evangelical according to the Pew Research Center, and 82 percent of those evangelicals identify as politically conservative or moderate.

"When I walked in there, I was so embarrassed," Elizabeth says of her first reluctant visit to a Planned Parenthood clinic. "These were all people getting free services to possibly kill their child. They were a stereotype, to me. But I was out of resources." The only place Elizabeth could think to turn was the one place she'd been taught forever to avoid.

There are many more women like her, all around the country. Women who grew up in conservative Christian environments that push abstinence-only education, unwavering anti-abortion attitudes, and adherence to the Republican party line—and who, out of necessity, are secretly visiting Planned Parenthood clinics for pap smears, birth control, STD tests, and other reproductive health services, including abortions.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

"We have many people from evangelical or born-again traditions who come to our health centers all across the United States," says Reverend Vincent Lachina, regional chaplain for Planned Parenthood of the Great Northwest and Hawaii. "Some evangelical and fundamentalist church staffers have even been patients."

Like Elizabeth, Megan's* childhood in the deep South was steeped in evangelical moral and social codes. She went to church every Sunday and attended a private Christian school from the fifth grade on. "It was a part of every aspect of my life. All the people I associated with were evangelical," Megan, now 34, recounts. At the time, she took their teachings to heart. "I'm a people pleaser and I wanted to do what was right. I got straight As. I played sports. I went along with it."

Then Megan went away to college and, after a year of dating her first boyfriend, decided she was ready for sex. She knew she needed birth control, but she was worried that if she used her health insurance to pay for it, her mother would find out she was sexually active. So Megan went to a nearby Planned Parenthood instead—easy enough to hide if she paid in cash. "Nothing with any sort of paper trail," she says.

To go to Planned Parenthood—a place many evangelicals associate only with abortions—was an uncomfortable step. But Megan had come to grips with the fact that she was already crossing a red line by engaging in premarital sex; she decided she might as well be responsible about it.

By senior year, Megan and her boyfriend had broken up. She was dating around for the first time and had stopped taking birth control. That's when a guy "took advantage" of her. She hesitates as she relates the incident, drawing in a sharp breath. Then: "There was a situation where I felt pressured to go beyond the point that I wanted to go."

After the assault, Megan discovered that she was pregnant. The news devastated her. Which explains why, despite her upbringing, she made an extreme decision: to return to Planned Parenthood and get an abortion.

Megan had done the moral math. It was worse to endure the disgrace of being an unmarried mother than it was to live with the secret—and the guilt—of terminating the pregnancy. "There was just so much shame in being pregnant and unmarried," she explains. "I thought, There is no way I can face my mother and my community back home with this." Again she paid for everything in cash. To this day, her family doesn't know.

It's largely due to the Christian right's vehement opposition that Planned Parenthood faces the very real possibility that it may have to shut down. Clinics around the country continue to close, one by one, state by state, due to lack of funding—just two weeks ago, Planned Parenthood announced that it would have to shutter four locations in Iowa and leave nearly 15,000 women without a primary healthcare provider after the state's mostly Republican congress voted to block funding to any medical facilities that provide abortions, despite the fact that a majority of Iowans support Planned Parenthood.

In fact, since the 1970s, taxpayer money has not paid for abortion services except in cases of rape, incest, or danger to the life of the mother. By law, public funding—which amounts to roughly $550 million per year, or 43 percent of Planned Parenthood's total operating budget—specifically goes to health services like birth control, STD testing, and cancer screenings instead.

That hasn't stopped the Trump administration from kindling the debate over whether welfare and Title X funding should go to the organization at all—an argument so heated that it threatened government shutdown last month.

Vice President Mike Pence, a self-proclaimed evangelical Catholic, made good on the promise he delivered at January's anti-abortion March for Life in Washington D.C. ("We will not rest until we restore a culture of life in America for ourselves and our posterity," he said that day) when, in March, he cast the tie-breaking Senate vote to allow states to stop federal grants for facilities that provide abortions. That legislation is why Iowa politicians were able to reduce their Planned Parenthood population by four.

The move was lauded by Christian organizations with a political bent, like Focus on the Family, the Family Research Council, and the Heritage Foundation, which have consistently lobbied for Planned Parenthood to be defunded. Focus on the Family founder James Dobson, a saintly figure in many evangelical homes, has said that "if you scratch around anywhere near the Planned Parenthood message and the function of Planned Parenthood, you see wickedness; you see evil." Franklin Graham, son of renowned evangelist Billy Graham and president of the Christian organization Samaritan's Purse, recently compared Planned Parenthood clinics to World War II concentration camps: "Raising funds for this organization is like raising money to fund a Nazi death camp—like Auschwitz, except for innocent babies in their mother's wombs." The Planned-Parenthood-as-modern-day-equivalent-of-a-concentration-camp trope has been picked up by Republican lawmakers as well. "This is as bad—or worse—as having one's name associated with Dachau," Kansas state senator Steve Fitzgerald wrote in a letter to Planned Parenthood after someone donated to the organization in his name. The Family Research Council published a 2016 report entitled "The Real Planned Parenthood: Leading the Culture of Death."

Data doesn't exist on just how many women who were raised in this faith actually patronize Planned Parenthood in private, which is a result of the very reason many of them go there: It provides anonymity. We do know that 13 percent of abortions conducted in this country are for women who identify as evangelical protestants, in addition to the 17 percent for more mainline protestants like Lutherans or Methodists, according to a 2014 study by the Guttmacher Institute. When you add in Catholics, that number rises to more than half.

I was raised in an evangelical culture myself and, while doing research for this story, I was taken aback by how often one Christian woman's experience with Planned Parenthood led me to another's, and another's, and another's. What I once believed was simply a handful of anecdotal instances became an undeniable trend, one that reached into many different backgrounds and beliefs. Some of the women in this article have left the faith in which they were raised, either altogether or adopted more progressive forms of it; others, like Elizabeth, still identify as evangelical Christian, a broad label that often indicates a born-again protestant who adheres to a fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible. Some of the women are from cities, others small towns. The common thread that runs through all their stories: Visiting Planned Parenthood was a risk—but one worth taking.

"It's a very difficult thing for them," says Lachina, the Planned Parenthood chaplain, who echoes the fact that secrecy is critical for the young Christian women who visit clinics. "They certainly don't want their parents to know that they're going to a Planned Parenthood facility," he says. "They want to be anonymous."

More valuable than even anonymity, Planned Parenthood provides religious women with honest medical information they likely aren't getting anywhere else: Research published in 2012 in the Journal of Women's Health found that weekly church attendance made women half as likely to be receiving any sexual or reproductive health services.

"They gave me an exam and birth control to help with my menstrual cycles, because they said my cycle might be causing problems with my cyst," Elizabeth says of her first Planned Parenthood appointment. "It was an education."

Still, the pressure of the community is hard to shake. Evangelical culture tends to be intentionally exclusionary, creating a sense of us-versus-them, and these women had engaged with what they were taught was the very worst of "them."

Rachel*, a pastor's wife, felt that pressure fiercely. "I grew up in a strict religious community. Planned Parenthood was the devil," Rachel says. "Our church talked about Planned Parenthood as a gas chamber and part of the new Holocaust."

But when she and her husband, whose job didn't provide health insurance, needed birth control, Planned Parenthood was the only option they could afford.

"During my exam, the doctor talked with me about all the different birth control options and referred me to a really detailed chart that showed the advantages and disadvantages of each. It was the most education I'd ever received on the subject," Rachel explains. "And she was the first doctor who didn't flinch or act judgmental when I told her I was a virgin until I got married."

"I felt really guilty afterward—both for using Planned Parenthood and for finding it so much more pleasant than I expected," she continues. "I was in ministry at the time, and that added another level of guilt because it felt so hypocritical. They put me on their mailing list, but I called and asked to be removed because I was so terrified someone would see the envelope and know. I lived in a liberal New England city, but I didn't even want the mail carrier to see it."

Julie Davis, a Christian marriage and family therapist in California, explains that trauma is often wrapped up in how young Christians are taught about sex, an act that's equated with lust and sinful desire. Young single women aren't supposed to want sex, let alone have it. And they're certainly not supposed to go to Planned Parenthood to enable it—or deal with the fallout. Despite the doctrine, 80 percent of unmarried evangelical young adults are, in fact, having sex, according to a widely-cited 2009 study from the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy—not much lower than the 88 percent national average. Davis says that for young women caught in this trap, shame can multiply and lead to destructive behavior like substance abuse, depression, or eating disorders later in life. "Culture and religion together set up a difficult situation for young women," she says.

Part of the issue is simply about openness. "If a young woman doesn't have a female mentor and she's experiencing something difficult or needs something regarding sexual health, where does she turn?" Davis asks. "Often it is Planned Parenthood, a place she knows she can go and they will help her."

Planned Parenthood was that kind of place for Heather*. She was 16 when she first became sexually active and needed birth control. An older classmate at her private Christian high school in Maryland told her that she could get a prescription at Planned Parenthood. Like Megan, she was worried that it would show up on her insurance and that her parents would find out she was having sex. But at Planned Parenthood, she was able to pay $10 cash for the Pill.

"We were all going there," Heather, now 27, says of her schoolmates, who used Planned Parenthood as teens. "I can think of six, seven, ten girls off the top of my head who were going there for birth control or pregnancy tests."

There was no sex ed at Heather's high school. "We weren't getting sex ed at home, either," she says. "Parents would be outraged if you talked about having sex. Girls would be starting their periods and they didn't know what was happening." Everything Heather and her friends learned about reproductive health was hearsay.

"You'd go to Planned Parenthood and they'd give you real information," she recalls. "They'd ask, 'Are you sexually active?' and tell you that you need to have a pap smear and should be tested for STDs. They would give us brown paper bags of condoms that we would giggle about. It was a vital resource."

Some young women aren't so fortunate. For Kristen Irving-Jordan, director and producer of Pro-Lifetime, a forthcoming documentary that examines the history of the pro-life movement, the stigma of Planned Parenthood was at first insurmountable.

At 22, she realized she had irregular hormonal issues. But her conservative background caused her to worry that if anyone found out she was on birth control to fix it, they would assume she was having pre-marital sex, a judgement she wanted badly to avoid. She had health insurance, but it wasn't extensive, and she would have to pay out of pocket to see a gynecologist. Kristen was busy building her career in the film industry and had little money to spare, so she considered going to Planned Parenthood since it was affordable and would provide her anonymity. Still, the idea was hard to stomach. "I remember calling the clinic and getting an automated recording asking me questions. Even with that, there was this sense of, I am engaging the devil right now," she says.

The morning of her appointment, Kristen awoke sick with shame. "Seeing it on my calendar, I thought, Can I do this? Ultimately I decided I couldn't."

Kristen didn't show up for her appointment, a pattern she'd repeat a few years later when she was without insurance and needed a physical due to chronic immune system deficiencies. Now, at 35, her experience has led her to explore the right-wing politics that dictated her guilt—and her health—in her 20s. The documentary has taken Kristen a long way, even to a Planned Parenthood anniversary gala in 2015. At the event, she was pleasantly surprised to witness a standing ovation at the announcement that abortions in their clinics were down 15 percent.

"I spent so many years motivated by fear and shame, and it wasn't just limited to sexuality. It defined my relationships and my life choices. My mental, emotional, and physical health were affected, and I suffered from severe depression and anxiety," she tells me. "It's sad, and I know I'm not alone. It's a big motivator for my film. I want to help expose the false narrative that has created an inconsistent pro-life ethic—one that demands birth but often doesn't care for that child once it gets here—and caused so many of us to be crushed by shame."

Like Kristen, Megan views her experience with Planned Parenthood as a formative one. "Of course it makes me sad," Megan says of having to terminate a pregnancy in college, "but what really makes me sad is that I feel like my upbringing put me in a position where being sexually assaulted was more likely to happen. I couldn't talk about sex in a healthy way."

Megan has come to the decision that Christian condemnation of Planned Parenthood is tainted by hypocrisy. "I think it's really silly. They characterize Planned Parenthood by one service, when really, what I think is most important is that the group provides preventive women's health services that are affordable," she says. "If you're really pro-life, then you should help people prevent unwanted pregnancies in the first place."

She's now married and has a young daughter, whom she's determined to give the chance she wasn't—to be a confident, strong woman with a mind of her own.

*Names have been changed.

-

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose"Princess Anne asked me if I'd have the surgery."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding Comment

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding CommentShe reportedly had lots of nice things to say, too.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down"

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down""Now he wants to do more and more and more. That's the problem."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Cecile Richards, Former Planned Parenthood President and Women's Rights Activist, Has Died at Age 67

Cecile Richards, Former Planned Parenthood President and Women's Rights Activist, Has Died at Age 67"Our hearts are broken today but no words can do justice to the joy she brought to our lives."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

What's the Holdup in Biden's Push for Paid Leave?

What's the Holdup in Biden's Push for Paid Leave?The president is proposing $325 billion to fund paid family leave—the strongest budget proposal in history—and pushing for free universal pre-K nationwide. But he faces opposition.

By Dawn Huckelbridge Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman Last updated

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich Published

-

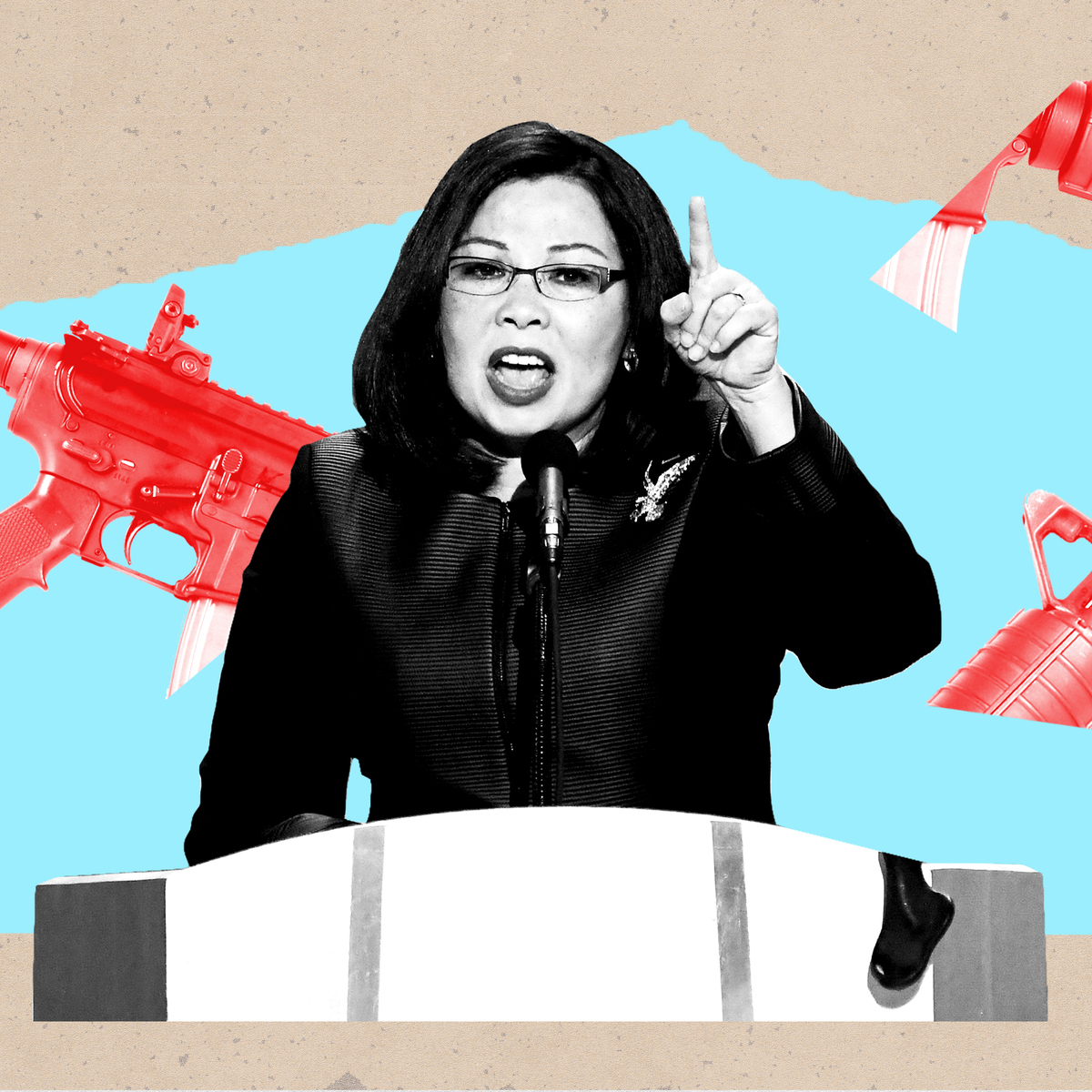

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth Published

-

Breaking Down President Biden’s New Executive Order on Abortion Rights

Breaking Down President Biden’s New Executive Order on Abortion Rights\201cWe feel really strongly, particularly given the tremendous amount of legal chaos that has ensued since this decision, that it’s incumbent on us to be careful.\201d

By Lorena O'Neil Last updated

-

14 Abortion Rights Organizations Accepting Donations to Support Their Fight

14 Abortion Rights Organizations Accepting Donations to Support Their FightFeatures 'Roe' is no longer the law of the land, but these organizations won't stop fighting.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published