Alicia Garza on How Women Are Battling Mass Incarceration

Black women are the fastest growing incarcerated population—and the group best primed to change the system.

The crisis of mass incarceration is shocking. Despite being 13 percent of the U.S. population, Black people make up more than 40 percent of the incarcerated population. Black women are the fastest growing population in prisons and jails. And one in four women have a family member who is in prison; for Black women, that number rises to nearly one in two.

It’s no secret that Black men are over-incarcerated in America. Michelle Alexander uncovered this shameful truth in her book The New Jim Crow. But Black men are not the only people being over-incarcerated, or who suffer from the impacts of mass incarceration. The movement to end mass incarceration is largely projected in the image of Black men, which means the impacts of mass incarceration on women and our families is often overlooked. Women are changing that.

The impacts of mass incarceration on women and our families is often overlooked. Women are changing that.

To me, this work is not unlike that of the abolitionists in the 1800s. Harriet Tubman led more than 300 enslaved people to freedom via the Underground Railroad. Today, Tubman’s spirit lives on in the movement to end mass incarceration through women like Gina Clayton, Founder & Executive Director of Essie Justice Group, and Jessica Nowlan, Executive Director of the Young Women’s Freedom Center (YWFC). Clayton maintains that “women are the re-entry system of this country.”

But millions of women bear the burden of incarceration in isolation and with shame. Whether you’ve been incarcerated yourself or have a loved one who is currently or formerly incarcerated, it’s not the first topic of conversation that arises at the dinner table—as evidenced in Essie’s report Because She’s Powerful. The impact of incarceration on women and their families is also not a topic of conversation among Presidential candidates—but with all the talk about the power of women in the 2020 elections, it should be.

Nowlan, Clayton, and thousands of women and gender non-conforming (GNC) people are leading a movement to change this dynamic —across the state of California and nationwide.

Jessica Nowlan speaks at the San Francisco Women's March in January, 2019.

The first step to building the kind of power that will change laws and impact elections is breaking the isolation and shame that incarceration produces. YWFC believes that America has something to learn from women and GNC people who are or have been involved in the system, and it starts by treating them like the leaders they are. Nowlan started working at YWFC 26 years ago as a young person who, by the time she was 18, had been incarcerated more than 17 times. Essie understands that these women are not broken, and that they are not waiting to be saved—they are waiting for an invitation into a community that shares their experiences and that is ready to change the systems that cause so much misery.

Change is their central charge: changing systems, changing laws, and changing lives. YWFC is closing San Francisco’s Juvenile Hall, where it costs $270,000 a year to house one young person. Essie pressures corporations to divest from the prison industry, and recently Google and Facebook banned ads for bail bonds on their platforms. Together, YWFC and Essie Justice Group have built a statewide coalition of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, working to make sure that no formerly incarcerated person, or their loved ones, get left behind, and they are explicit that this movement is for everyone, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. They are advancing policy platforms in California such as Freedom 2030, which has as a goal the suspension of mandatory minimum sentencing and sentence enhancements, or ending cash bail.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

A bold agenda to bring incarcerated people back home to their families is long overdue.

Next month, Essie will do as it does each May and raise hundreds of thousands of dollars to bail mothers from jail for Mother’s Day. Each time they free someone, they bring that person into the movement so that they can go back to free their loved ones who are still locked up and locked away. They invite people who are currently incarcerated to nominate a loved one for the Essie Sisterhood, a nine-week healing justice and leadership development program that provides connection, community, and support for the women on the outside who are holding the pieces together, awaiting the day when their loved ones are able to return home.

Recently, I met with a Presidential candidate who asked how to make their platform more appealing to the communities I care about. I responded that a bold agenda to bring incarcerated people back home to their families—one that would redirect the billions of dollars invested in punishing, incarcerating, and demonizing people who make mistakes into supporting them and their families so they can be more than the worst thing they’ve ever done—is long overdue. For women, Black women in particular, the biggest challenge we face is not simply equal pay or sexual harassment and violence. It is the lack of resources and power for the glue we provide that puts our families and communities back together again.

While I’m still waiting to hear back from said candidate, these women are waiting for no one. Women have always persevered, whether someone got back to us or not. On the road to 2020, Nowlan, Clayton, and the thousands of women they organize, are changing laws, changing culture, and building power so that they will no longer be ignored. Clayton’s grandmother would respond incredulously when asked how her own grandmother was able to be powerful in the face of adversity, “How’d she do it? She had sisters!” The Underground Railroad is alive and well.

RELATED STORY

-

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose"Princess Anne asked me if I'd have the surgery."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding Comment

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding CommentShe reportedly had lots of nice things to say, too.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down"

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down""Now he wants to do more and more and more. That's the problem."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman Last updated

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich Published

-

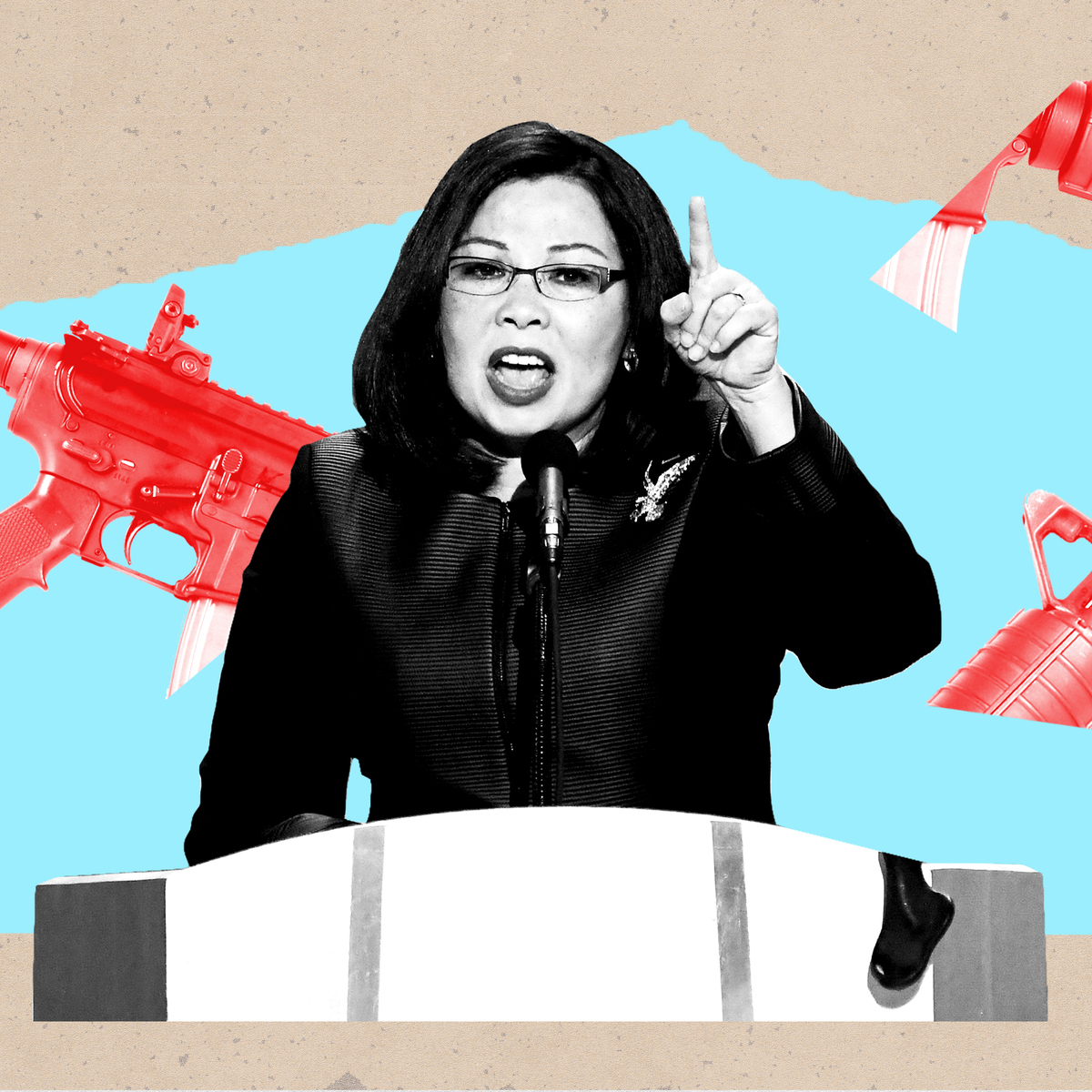

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth Published

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast Published

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan Published

-

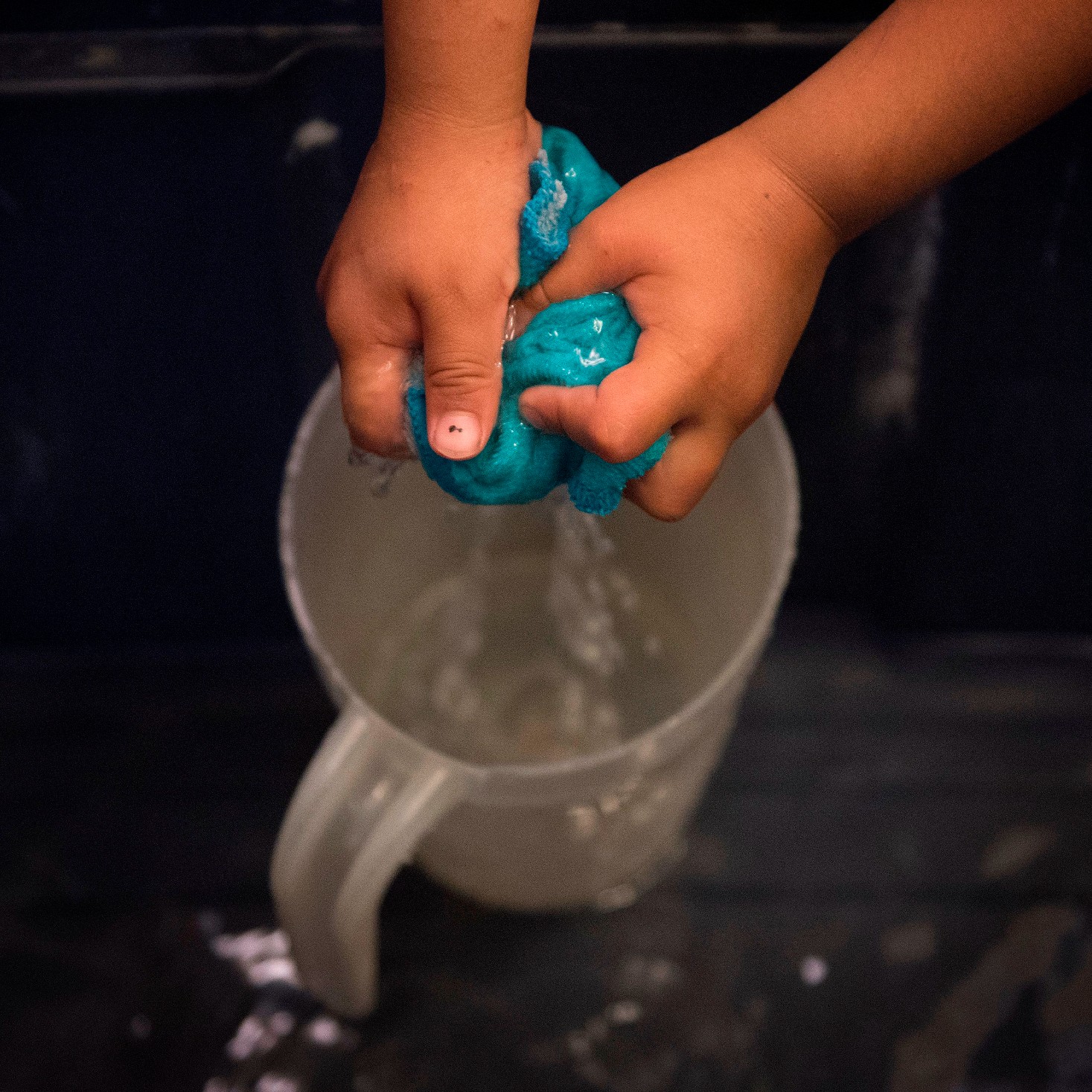

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein Published