The New President Of Planned Parenthood Has Big Plans For The Future

At age 16, Leana Wen sought birth-control information at a Planned Parenthood health center. Now, 20 years later, she returns to that same clinic—this time as president.

Like many teenagers, when Dr. Leana Wen was 16, she was curious about birth control but wasn’t exactly getting top-notch sex education at home. “It’s not something my parents ever talked to me about,” she says. “I think the closest my mother came was when she told me: ‘You need to finish school.’” She intended to graduate but had no idea what getting her diploma had to do with sex; she needed real information.

Wen, now 36, remembers feeling terrified when she walked into a health center run by Planned Parenthood in Pasadena, California, near where her family was living at the time. “If you were to ask me the color of the wallpaper or number of chairs, I would have no way of knowing that,” she says, “but I remember the emotion of sitting in that waiting room feeling so scared and anxious.” Wen found some pamphlets with information on contraceptives and was just about to take them and run when her name was called by the receptionist. She doesn’t recall the specifics of the care she received at that appointment, but she left Planned Parenthood knowing she had found her people. “The nurse was so kind and so normal and talked to me in the way I needed, which is as a person, as a peer, without judgment,” Wen says. “I remember the relief that I felt after I talked to somebody who I thought really got me.”

Twenty years later, on a sunny morning in late January, a banner reading “Welcome home, Dr. Wen,” greets her as she walks into that very same health center as the newly named president of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA). Wen is the first doctor to lead PPFA in nearly 50 years, and today’s visit is the third stop on her national listening tour to 20 of the organization’s 53 regional affiliate offices that run Planned Parenthood’s more than 650 health centers, which provide care for some 2.5 million people nationwide.

As part of the tour, Wen is learning about local initiatives that could be rolled out at clinics across the country. In the suburbs of Cleveland, Wen learned about an outreach program targeting African Americans, whose infant-mortality rate is twice that of the general population; in Miami, she heard about how employees went door-to-door with prevention kits during the Zika epidemic. Here, Wen seems particularly interested in how Planned Parenthood of Pasadena and the San Gabriel Valley has expanded so quickly (it had one health center in 2004 and will have seven by 2021), a flow plan that gets patients in and out of most appointments in an hour or less, and recently added services including HIV prevention, hormone treatments, and mammograms.

Hiring Wen, an emergency room physician who most recently served as the public health commissioner in Baltimore, seems to be a targeted effort by Planned Parenthood to remind pundits and the public that while the organization remains committed to providing abortions, they also offer a plethora of high-quality, potentially life-saving healthcare services that have nothing to do with the politics of terminating pregnancies. Her tone-setting first campaign, “This Is Healthcare,” rolled out just three weeks into her tenure (which began November 12), affirmed that notion. “For so many patients who come to us, we are their only source of care,” Wen says. “I wanted people to know what they can count on us for.” Planned Parenthood could even begin offering services not typically associated with reproductive care like treatment for diabetes, mental health, and opioid addiction, an issue she tackled in Baltimore by issuing a city-wide prescription for the overdose-reversing drug, Naloxone. (The program is credited with saving nearly 3,000 lives in three years.)

Listening may be the stated purpose for the national whirlwind, but the tour is clearly also about introducing Planned Parenthood’s employees to their new leader to assure them that the organization is in good hands following the departure of Cecile Richards, the political powerhouse who led PPFA for 12 years. There are so many speeches, handshakes, and requests for selfies that spending a day with Wen feels like being with a politician on the stump. She begins talks by highlighting her personal history as an immigrant.

For so many patients who come to us, we are their only source of care. I wanted people to know what they can count on us for.

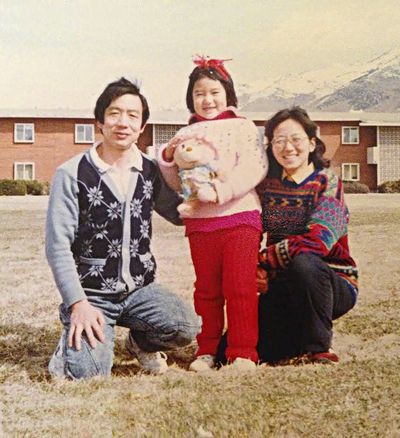

Wen was born in Shanghai to a family of political dissidents who rebelled against the communist regime’s crackdown on free speech. Her dad spent much of her childhood in jail, and when he wasn’t imprisoned, her parents focused on leaving the country for a better life elsewhere. “My parents tried for years to leave China, but it was very difficult,” she says. In 1990, when Wen was seven, her mother received a student visa to study at Utah State University in the city of Logan. Several months later, just before Wen’s eighth birthday, she and her father left to join her mother.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Her dad was sick at the time—he had a perforated ulcer and had been in intensive care—but he didn’t want to miss his chance to go to the U.S. Neither he or Wen spoke English, but her grandfather did, and he tucked little pieces of paper reading: “Help, my father fainted. He has an ulcer. He needs help immediately,” and “I don’t speak English. My mother is waiting in Utah. Here is how to reach her,” in her pockets just in case anything went wrong. “When I said goodbye to my family in China, I thought it was really goodbye—we did not expect to see them again,” Wen says. “I thought that was the last time I would hug or even speak to them.” (She eventually reunited with her aunts and uncles on a trip to China some 15 years later.)

Leana Wen with her parents.

By the time she and her father made it to Utah, they had just $40. They also had the misfortune of arriving in December. “I had never seen snow,” Wen says. “I remember my parents said, ‘We have to save in every way,’ so we went without heating. We were just really cold all the time.” She had no winter coat or boots either. “The only thing we could do was layer on clothes,” Wen says. “I would wear five pairs of pants and six sweaters or something.” One day, a week or so after they arrived, they heard a knock on the door and found a large bag of clothes sitting outside. A neighbor had collected items for them from her church. “They must have seen us really struggling,” Wen says. “There were clothes, blankets, snow boots, and other things we needed to survive.” She says she’ll never forget the act of kindness. “I don’t even know who to thank, but I feel very grateful to the people there,” she says. “They really embraced us as a family and helped me to learn English. I was that kid in school—the only one who didn’t speak English. There was no English as a second language instruction, it was just me. The other kids were so tolerant and friendly. I wouldn’t be where I am now without the teachers and students there.”

Her parents worked multiple jobs to get by. Her dad washed dishes in restaurants; for a while, he worked in a cheese factory (“To this day, he can’t eat cheese,” Wen says). Her mother, a full-time student, worked as a cleaner at the university and at a hotel. When Wen was 10, her family moved to California, living for a short time in Compton before settling in East L.A. “There were multiple times when we couldn’t make the rent and we had to pack up everything because we were being evicted,” Wen says. “We stayed with my father’s friends. A few times we had to find a motel room. A couple of times we lived in homeless shelters.” They didn’t have health insurance, and Wen remembers her mom, who received care at Planned Parenthood, talking about the clinic as “the place that she could go when she couldn’t afford to get care anywhere else,” Wen says. “That’s why I always associate Planned Parenthood with being a place that gives people refuge.”

I was that kid in school—the only one who didn’t speak English. The other kids were so tolerant and friendly.

During those early years, Wen remembers, her mom once came home crying from her job at a video store and told her dad she’d been sexually harassed by her employer (they lived in a studio apartment, so Wen overheard a lot). “I don’t know the extent of it,” Wen says. “I know she was being verbally and maybe even physically abused by the employer, but we needed the money.” Her mother was also worried because of the family’s immigrant status; they had applied for asylum but hadn’t yet been granted it. (They eventually became citizens in 2003.) “She felt like her employer had all the power—that if she complained in any way, or if she even fought back, she would be putting our entire family at risk,” Wen says. “I remember hearing the shame in her voice as she was telling my father all of this. I think about it a lot now that I am an employer and a manager. I think about my responsibility to prevent anybody else from experiencing that same fear and intimidation that my mother felt.”

In 1996, when she was 13, Wen began attending California State University via its early entrance program, graduating summa cum laude in 2001 at age 18 with a degree in biochemistry. She then attended medical school at Washington University in St. Louis and also completed two master’s degrees, one in modern Chinese studies and another in economic and social history at the University of Oxford, where she was a Rhodes Scholar; she also met her now husband, Sebastian, an information-technology project manager, in the U.K. After a clinical fellowship at Harvard Medical School and residency training at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, she went to work as an attending physician in the ER at George Washington University before becoming the public-health commissioner in Baltimore (or the city’s “top doctor” as the position is often called). As commissioner, Wen successfully sued the Trump administration for cutting funds from the Teen Pregnancy Prevention program.

Her years as a physician made her an especially good fit for her new role. When she shares anecdotes of patients being denied care, it’s not theoretical—they’re real stories from her life experience, like one she often recounts of caring for a woman who was denied an abortion and died after trying to give herself one at home (by the time Wen treated her in the E.R. it was too late). When she talks about the Trump administration’s domestic gag rule (forthcoming at press time), which is expected to prevent any organization that accepts Title X funds—which Planned Parenthood uses to offset the cost of exams, cancer screenings, and birth control for-low income patients—from providing information on abortion, her passion is palpable. “I find it unconscionable and unethical that I am being told by the Trump Administration, or any politician, what I’m able to say to my patients,” she says during a luncheon speech at a country club to donors and local board members. “The oath I took is to provide them the best information that I can and empower them to make the best decisions for themselves, not to censor what I can say based on what a politician believes.”

(Editor's note: On February 22, 2019, the Trump Administration formally banned federal family planning funds from going to providers who offer or refer patients to abortion services.)

Patients are not trying to make a political statement—they are trying to get care.

That conviction should serve her well for the fight ahead. Not only is Planned Parenthood preparing for the possibility that Roe v. Wade will be dramatically altered or overturned now that the Supreme Court has five conservative-leaning justices, she was also dealt her first internal crisis a month in, when Planned Parenthood employees alleged in The New York Times that they were sidelined or ousted because they were pregnant. Wen says the organization is investigating the claims and taking swift action to ensure “we truly live the values that we espouse.” The organization is also looking into instituting paid parental leave nationwide (currently some affiliates have it, others don’t). “We have to do better,” Wen adds.

When she was first approached last spring about the opportunity at Planned Parenthood, Wen says she almost didn’t return the call. She had just returned to work seven weeks after giving birth to her son, Eli, and was figuring out how to pump every three hours and the other difficulties that come with being a working mom. “I could not even imagine even thinking about another job,” she says. But then two things happened: Someone randomly gave her a copy of Richards’ book Make Trouble, and she gave a commencement speech the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health during which she called on students take action. “I told them we all have to step up, because as frustrated as we are, things are not going to change unless we do everything we can,” Wen says.

She quickly realized she had to take her own advice. Wen took the first meeting at Planned Parenthood mostly to offer insight. Regardless of who got the job, she wanted to present helpful ideas to the organization that had touched her life and that of her mother, who died from breast cancer in 2010. She says she urged them “to look at their work from a health-care lens because that’s what Planned Parenthood means to the patients who come. They’re not trying to make a political statement—they are trying to get care,” Wen says. “That’s what it meant to my mother. That’s what it meant to me as a patient.” Several months and meetings later, “Here I am!” she says. And as long as she’s in charge, she’ll work to keep open the doors that once welcomed her.

A version of this article appeared in the April 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

RELATED STORY

Kayla Webley Adler is the Deputy Editor of ELLE magazine. She edits cover stories, profiles, and narrative features on politics, culture, crime, and social trends. Previously, she worked as the Features Director at Marie Claire magazine and as a Staff Writer at TIME magazine.

-

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"Here's what to know about the Max series's breakout star, who just so happens to come from TV royalty.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an Apology

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an ApologyThe season finale of the smash Max series proved that the most unlikable character on TV may just be the hero we all need.

By Jessica Toomer Published

-

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 Million

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 MillionHulu's answer to 'The Traitors' is here.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Cecile Richards, Former Planned Parenthood President and Women's Rights Activist, Has Died at Age 67

Cecile Richards, Former Planned Parenthood President and Women's Rights Activist, Has Died at Age 67"Our hearts are broken today but no words can do justice to the joy she brought to our lives."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

What's the Holdup in Biden's Push for Paid Leave?

What's the Holdup in Biden's Push for Paid Leave?The president is proposing $325 billion to fund paid family leave—the strongest budget proposal in history—and pushing for free universal pre-K nationwide. But he faces opposition.

By Dawn Huckelbridge Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman Last updated

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich Published

-

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth Published

-

Breaking Down President Biden’s New Executive Order on Abortion Rights

Breaking Down President Biden’s New Executive Order on Abortion Rights\201cWe feel really strongly, particularly given the tremendous amount of legal chaos that has ensued since this decision, that it’s incumbent on us to be careful.\201d

By Lorena O'Neil Last updated

-

14 Abortion Rights Organizations Accepting Donations to Support Their Fight

14 Abortion Rights Organizations Accepting Donations to Support Their FightFeatures 'Roe' is no longer the law of the land, but these organizations won't stop fighting.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published