Women Won Big Last Night. Now It's Time to Get to Work

We can't allow a one-time wave to fool us into thinking we've achieved equality.

Last night, women made history—and the women who won their elections did so largely thanks to the women who turned out and voted for them. The election results were also a female-led indictment of President Trump, whom many voters credited with motivating them to show up to the polls. It will take a few days to fully parse the data and figure out which subgroups of women were the biggest drivers of this victory, but we know already that much of the credit goes to African-American women, Latinas, young women, single women, and college-educated white women. When the triple-digit numbers of newly-elected women take office in January, it will mark a new era in American politics.

Our job now is to sustain it, leverage it, and build on it.

Even with last night’s gains, women remain a significant minority in Congress, and women of color even more so; American halls of power remain overwhelmingly dominated by a minority of our citizens (white men). It’s crucial to take pride in last night’s wins, but not to fall into the too-common trap of women’s representation: Seeing a few more women in the room and concluding that we’ve reached equality. Headlines and tweets declaring women now in charge are more aspirational than accurate—women hold only about a quarter of seats in the House.

Still, momentous gains were made, among them the crumbling of the assumption that women don’t perform as well as men in difficult elections. It is true that sexism dogs female candidates, and that women can be more competent and qualified than their opponents and still lose; Clinton’s loss remains our primary example of that dynamic. But it does not follow that running women poses too big a risk, or that the state of our democracy is too fragile to gamble on female candidates running in sexist electorates. To the contrary, the only way to truly break down electoral sexism is to run women, again and again and again, until it’s no longer notable that women are running.

It's crucial we don't fall into the too-common trap of women’s representation: Seeing a few more women in the room and concluding that we’ve reached equality.

As it stands, we associate political charisma, authority, and presidentialness with men. Just look at the reactions to last night: A slew of women won in districts that were thought to be unwinnable, but the Twitter chatterati pointed to one man who came close but still lost as the leading presidential contender in 2020. This makes sense. We have only had male presidents, and all but one of them have been white. Our idea of “president” is intrinsically tied to “male.”

That trickles down to leadership roles generally—it’s not just that we’re used to seeing men in charge, it’s also that our entire understanding of authority and power is coded as male. Women who appear on the radio or on television are often subjected to complaints about “vocal fry” or some offending bit of clothing, hair, or makeup; men, whose faces and voices are presumed to belong in media, aren’t given a second thought. Female professors are routinely rated lower than male ones, not just in the classroom but in hypothetical scenarios in which the same person with the same instruction is alternately “Paul” or “Paula.” These are subtle, unintentional biases, but they fundamentally shape women’s political prospects.

Related Stories

Which is part of why last night is such good news. The only way to normalize female authority is to put more women in positions of authority; the only way to change assumptions of what political charisma and presidential potential look like is to change who is in elected office and who is in the pipeline for the presidency. A one-time thing—the first black president, the first female president—doesn’t undo centuries of baked-in stereotypes. This work has to be persistent.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

This is where women, and the men who also want a more egalitarian future, come in. Female success at the polls is about much more than women running for office (although that’s a crucial part of it, and more women should run). It’s about setting up a system that allows women to succeed—not in spite of long-standing obstacles, but because those obstacles have been systematically torn down.

It’s about setting up a system that allows women to succeed—not in spite of long-standing obstacles, but because those obstacles have been systematically torn down.

With Democratic wins not just in the House, but in Governor's Mansions and state legislatures across the country, the time is now to push for legislation that will allow this female successes to be replicated, in politics and across industries. First on the list has to be combatting voter suppression, an issue that animated this election and no doubt contributed to losses in Florida and Georgia. Florida’s new law enfranchising felons who have served their time is an excellent model, and should be on the To-Do list of every Democrat-dominated legislature. Feminists always focus heavily on reproductive rights, and for good reason: If a woman cannot plan when and whether to have children, there’s not much else in life she can plan. Free, easily-accessible contraception and accessible, affordable abortion for all women should no longer even be up for debate; it’s foundational for women’s equality. So too are paid leave and affordable childcare. Too many women have to deviate from their professional lives because there simply are not basic systems in place to ensure people can have children and also hold down jobs—or better yet, pursue their professional dreams. The burden of childcare continues to fall mostly on individual women, which in turn feeds into the idea that childcare is women’s work—and a woman's burden to figure out for herself. Finally, well-funded public education, including higher education, is crucial. We’ve seen in the past several elections just how defining education can be: that women who have finished college are less dependent on male partners, and freer to vote for politicians and policies that benefit women as a whole. Women who have access to higher education also have better life outcomes generally: They live longer, they divorce less often, and their kids do better all around. Expanding educational opportunities for all Americans is crucial for our national stability and our economy, but it has specific benefits for women.

Yesterday’s pink wave marks an historic moment for American women. But if we want to make that movement even stronger—if we want to make sure that women in office are not a one-time wave but a permanent fixture of our democracy—we have to do more than just elect women. We have to create the conditions for them to thrive.

From explainers to essays, cheat sheets to candidate analysis, we're breaking down exactly what you need to know about this year's midterms. Visit Marie Claire's Midterms Guide for more.

[editoriallinks id='74242ec3-e5dd-4de6-8e4f-8b81a6ac07d4'][/editoriallinks]

Related Story

Jill Filipovic is a lawyer and journalist who covers gender issues, politics, and global affairs.

-

The "Frightening" Easter Prank William Played on Eugenie

The "Frightening" Easter Prank William Played on Eugenie"Prince William has just stood on a chair and bitten the mouse's head off."

By Amy Mackelden

-

A Resurfaced Photo Reveals Charlotte's Royal Lookalike

A Resurfaced Photo Reveals Charlotte's Royal Lookalike"The Spencer genes are so strong."

By Amy Mackelden

-

Why Prince Andrew Attended Royal Family's Easter Service

Why Prince Andrew Attended Royal Family's Easter ServiceIt was previously alleged King Charles's "patience was wearing thin" with his brother.

By Amy Mackelden

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

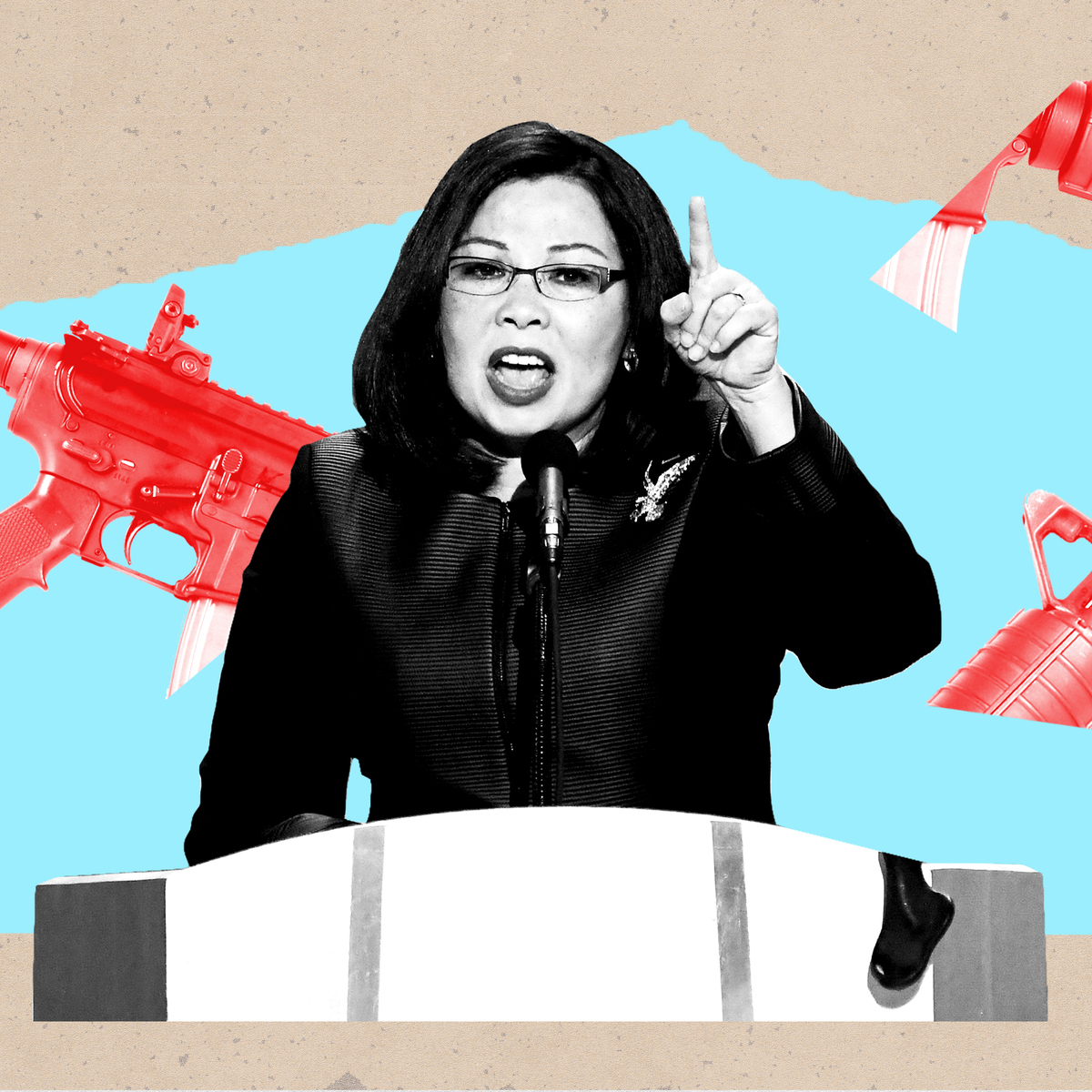

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan

-

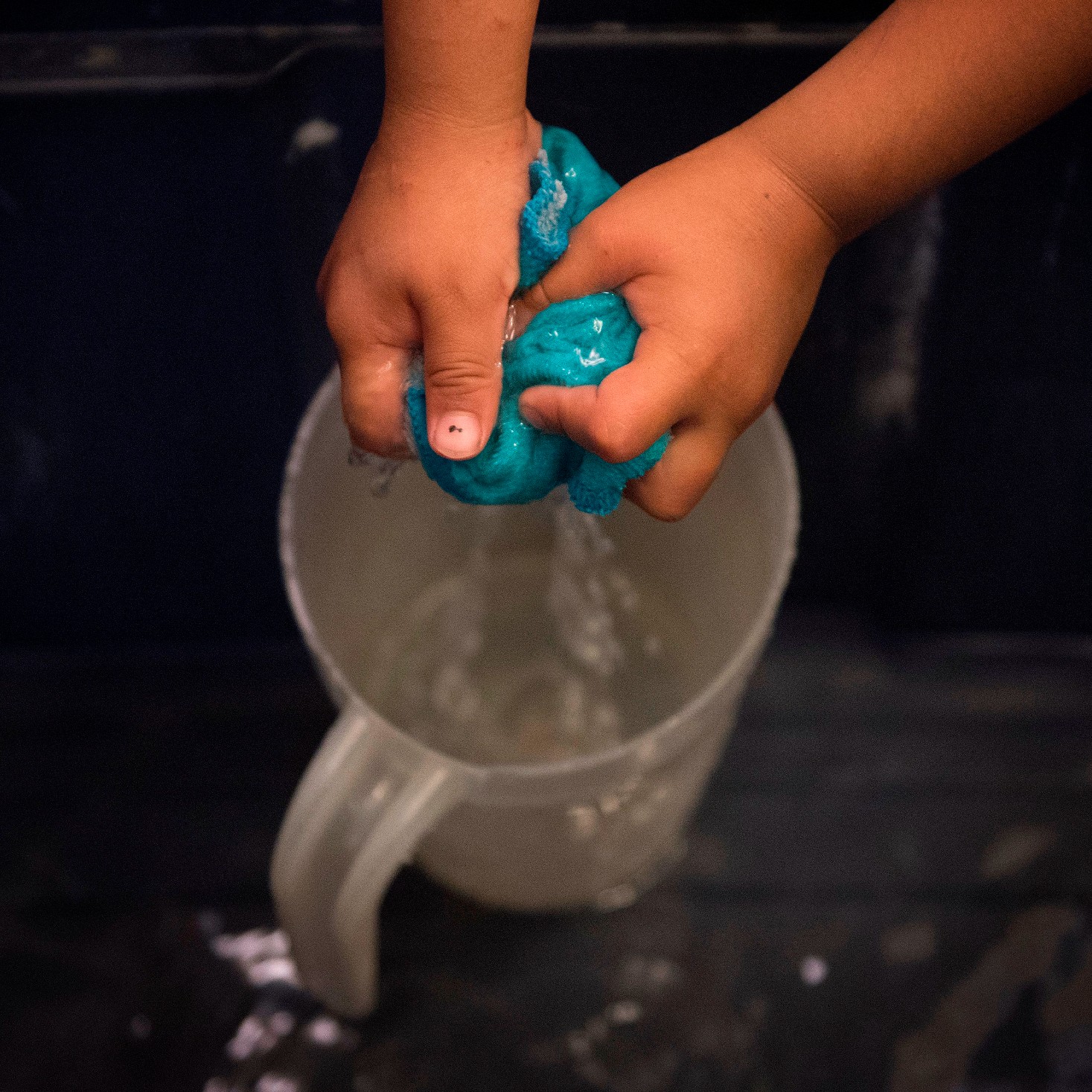

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein