How a Normal Rhode Island Girl Got Sold into Sex Trafficking

So many Americans think sex trafficking is a heinous practice that happens somewhere else. Here, undeniable proof of its human toll right here in our own backyard.

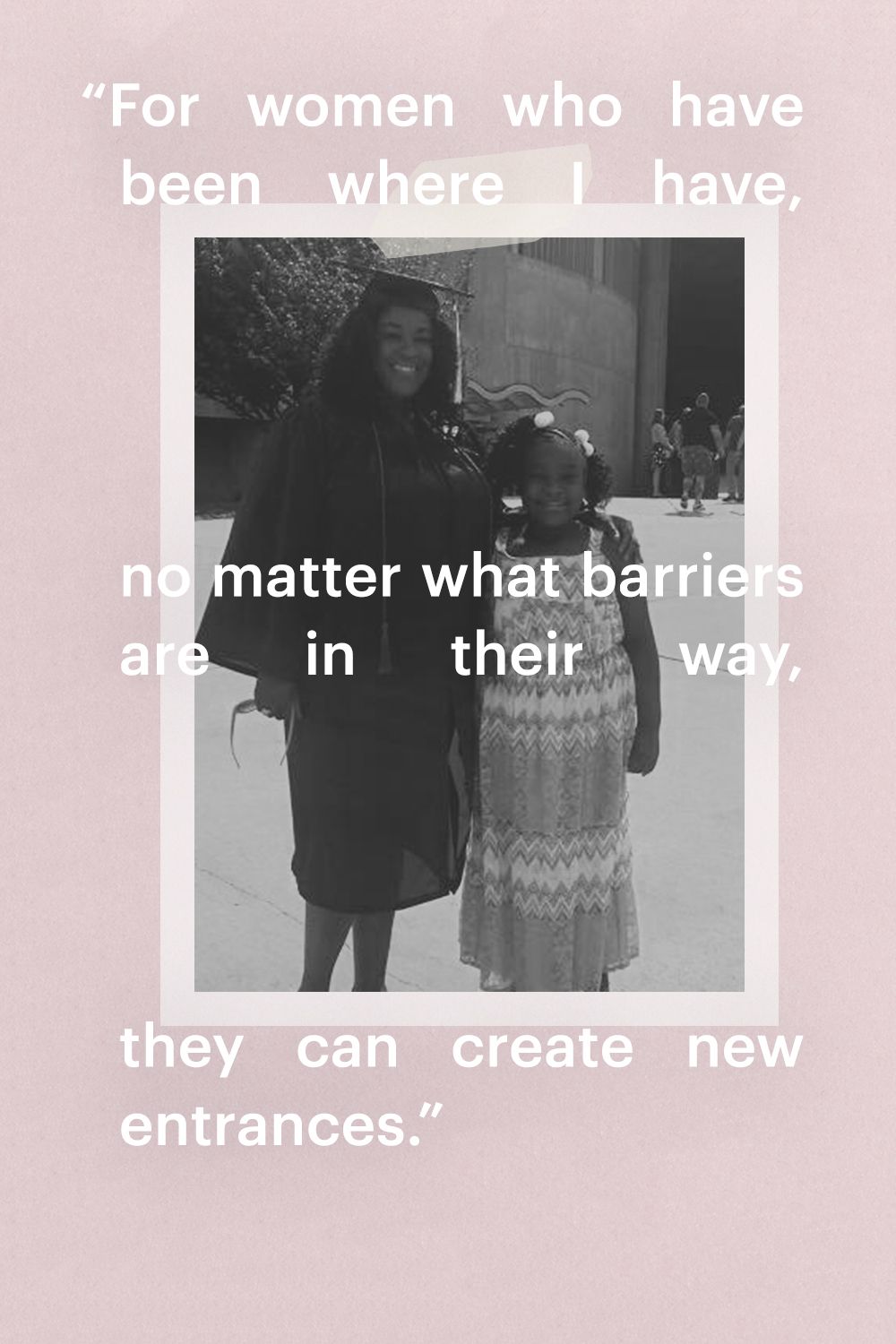

Patrice Maina is pretty sure she's the only former sex trafficking victim out of the thousands of people at her college graduation.

Five-foot-10 with curly hair and a warm smile, she steps into the auditorium at the Community College of Rhode Island, the largest community college in New England. She wipes her eyes and clings to the hand of her 9-year-old daughter. In the audience, her mother blows her air kisses.

A pulsing sea of black caps and gowns surrounds her. The other graduates exchange high fives and congratulations. They've waited years for this moment. They've been through so much to get here. But few have been through more than Maina.

One summer afternoon when she was 12, in 1992, Maina played hide and seek in a Providence park with three boys around her age. Looking for the best possible hiding place, she crouched near a grove of peach trees, whose sweet fruit she sometimes sold door-to-door for 10 cents each. When the boys found her scrunched in the shadows of the branches, they took turns brutally raping her.

"I just know that that particular day, my life changed," Maina recalls with a chill. "I started feeling like all I was to men was just something to do. A piece of meat."

Her self-esteem was shot, and adolescence didn't help: A growth spurt during her freshman year of high school left her inches taller than her classmates and 205 pounds. As the only black student, she remembers eking out a lonely existence as "the tallest one, the biggest one, the blackest one."

"Patrice felt out of place because the town was predominantly white," her mother, Theresa, remembers. "Making friends was very hard."

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

When she turned 19, Maina got a housekeeping job at the Biltmore, a hotel in downtown Providence. She was waiting for the bus after work one evening when a couple asked her to play a game of Three-Card Monte. They seemed friendly and the game seemed innocent enough—though games had gotten Maina into trouble before.

The rules were simple: Players bet money on which bottle cap a Cheerio was under. Maina agreed to bet her last $10. When she lost, the couple—Damon* and Madison*—persuaded her to play again. By the time it was dark out, they had persuaded her of something else: to accompany them back to Rochester, New York. The way Maina remembers it, she didn't need much convincing: "I really didn't like Rhode Island. I just was a broke-down person. And when I was out there traveling to Rochester, I could be someone else. I could be anybody."

At first, life in Rochester was pleasant and uneventful—Madison and Damon were covering Maina's living expenses so she didn't have to worry about money. But then Madison made a surprising suggestion for repaying them: She told Maina to go on a chat line where men could ask her to engage in sexual activity. "It was like an escort service, but not a professional one," Maina says now of the manipulation—she was broke, young, and far away from anyone who could help her. Sex work was presented as the only option.

That night, Maina had sex with an Armenian man who reeked of body odor. He would be her first client of hundreds. "That whole night, I just felt like the filthiest person on the planet," she says. "But then as days went by, and weeks, it became really easy."

This is when Maina began to piece together that Damon and Madison ran a complex sex trafficking operation masquerading behind their card games and casual conversation. Damon acted as a pimp, pocketing the women's profits in exchange for protection. Madison's job was to oversee the women and provide encouragement.

Maina herself, she now realized, was one of those women.

"I need to come back to Rhode Island," she told her mother one night months later, her voice raw and panicked over the phone. "I did something stupid. I'm scared. I'm way out here in Rochester, and I don't know what to do."

"You need to get yourself together," her mother said, "before you come back."

It would be a long time before Maina came back. Still stinging from her mother's rejection, she made an impulsive decision to hit the road. She hopped on a bus to Niagara Falls. From there, she travelled to Worcester, Massachusetts; Atlantic City, New Jersey; Washington, D.C.; Las Vegas, Nevada; Oakland, California. She paid her way through prostitution.

In each city she found a unique culture surrounding underground sex work. The girls on the East Coast wore revealing clothing and strutted the streets. The girls on the West Coast dressed and acted more low-key. But there was a universal language: Clients were called "johns," and groups of women who belonged to the same pimp were called "stables." White girls earned higher "quotas" than black girls, pocketing $3,000 for the night compared to $1,500.

Maina soon became an expert at navigating this world. She learned the names of the amateur pimps who could defend her and the bars where she could find johns. She learned to avoid eye contact with black men in cars who could kidnap her—a practice known as "honapping." Most of all, she learned to protect herself by hiding pepper spray and a razor in her wig, and to guard her profits by inserting condoms full of money inside her.

"Once you get into the lifestyle of sex trafficking and prostitution, it becomes almost as if that is society," Maina says. "That is the life that you're living, so everything in it is your main focus, and everything outside is really a separate reality."

It was in that extreme society, deep in the heart of Las Vegas, where Maina developed an addiction to crack cocaine. She was using when she first met Loni*, a pimp who drove a muscle car, snorted heroin, and seemed, to Maina, like a real-life Casanova. He kept a stable of 12 women—Maina made lucky number 13.

She traveled with Loni back and forth from Las Vegas to California. She soon got to know the other women in his stable, or her "wife-in-laws." Violet* would snap into vicious outbursts. Amber* cooked. Roxy* enjoyed the coveted role of "bottom bitch," granting her the privileges of sleeping with Loni and shooting up heroin.

The work paid. But the work took its toll.

Loni expected Maina to hustle from 8 p.m. to 9 a.m. every night—except Sunday—and to sleep on a couch in the garage. He gave her a few hundred dollars of "front money," which she used to blend into the crowd at casinos by buying drinks and gambling at slot machines. Loni didn't use the nicknames she gave herself—"Vegas," "Emerald," "Ebony." Instead he called her "big bitch."

Some nights, Maina would wake up to find Loni on top of her, his body thrusting over hers with sickening force. She would get up the next morning, battered and bruised, to find him sleeping naked beside her.

One of those nights, Loni got angry at Maina because she had used all her earnings to buy crack cocaine. He immediately brought her to a Walgreens, where he sold her on the spot to a drug dealer waiting outside. The amount: $120.

Back at his house, the drug dealer forced Maina to have sex with him in front of his girlfriend. Afterward, when she tried to leave, he pulled out a gun and said, "You're not going anywhere." Maina waited until he was intoxicated, opened the door, and ran, without shoes on, as far as she possibly could.

Maina in 2000 (left) and 2014 (right)

She knew then that she wanted to return to Loni. Despite his violence, he had a special way of making her feel wanted, of telling her she was big and beautiful, of convincing her—sometimes—that she could be more than a cash transaction.

Maina showed up at Loni's den the day before Thanksgiving. He threw her down the four steps leading to the garage, and at the bottom of the steps, he raped her.

When Maina woke up, it wasn't because she was in pain or because light was creeping in through the clouds. It was because Roxy had stuck a needle in her arm. "That was the first time I ever did heroin," Maina says. "I woke up to it."

On New Year's Day, Maina felt sick to her stomach. She tried to work, but she kept throwing up, so the other women in the stable wrapped her in a blanket and called an ambulance. At Alameda Hospital, a nurse instructed her to pee in a cup—the urine sample indicated that Maina was five months pregnant.

She felt frantic. Agitated. But maybe not surprised.

The biggest shock actually came later, after she'd been wheeled into the ultrasound room on a stretcher and rolled into position in front of a black and white screen. It was jumpy, making rapid jerking movements. "It's not the screen," the nurse said. "It's your baby. She's withdrawing."

As Maina stared at her unborn baby's tiny body convulsing with heroin cravings, she had one of those elusive moments that only happens in times like these: She saw herself from the outside. "I was 26, addicted to heroin, addicted to crack cocaine, a prostitute. A lost cause."

"Mom, I'm pregnant," Maina whimpered into the phone. "Can I come home?"

Theresa broke down crying. It was time to get her daughter back.

But as relieved as they were to be reunited at home in Rhode Island, Maina had an even harder road ahead: the double agony of withdrawal and pregnancy.

Her daughter, Ja'naya, was born on June 30th, 2007.

Maina says her record now includes nine arrests for prostitution in three states, plus Washington D.C. She hardly ever mentions her time behind bars, like her incarceration at a California facility known as "the farm," where she had to wad up toilet paper into makeshift pillows to make the bench she slept on more comfortable.

"My record is a barrier," she says of her attempt to get her life back. Many sex trafficking victims, Maina included, raise strong objections to being labeled a "prostitute"—the term stigmatizes them as choosing to engage in illegal activity, a common misconception that's widespread, from law enforcement to the mainstream media.

At the same time, a national conversation about the validity and autonomy of sex work is starting to emerge, as activists and feminists push to decriminalize prostitution in the United States. The debate often boils down to two sides: those who believe women are empowered to choose to engage in sex work, and those who believe many women don't have the option to choose otherwise.

Sex trafficking is a multi-billion-dollar industry in the United States, generating an estimated $290 million in Atlanta and $40 million in Denver (sex-trafficking hotbeds) each year, according to a 2014 report by the Urban Institute. And cases are "grossly underreported," says Lara Powers, director of National Human Trafficking Resource Center's hotline. This means that despite how commonly women and girls are sex trafficked, the public has no idea how widespread the epidemic truly is.

Even medical practitioners can be in the dark, says Hanni Stoklosa, an emergency medicine doctor at Brigham and Women's Hospital and founder of HEAL Trafficking. "When I didn't know that trafficking existed in the United States, I was missing these cases all the time," Stoklosa says. "If you don't know something exists, you're not going to see it at all."

Despite not being "seen," sex trafficking victims who have prostitution charges on their record—who essentially bear the legal responsibility for someone else's abuse—face hypervisibility in the professional world. Finding employment after the fact can be difficult. Meredith Dank, a researcher at the Urban Institute, has interviewed dozens of women with prostitution charges who say their record is a "huge road block" to obtaining a job. "Sometimes they were given the offer of explaining why they have this record," Dank says, "but no woman wants to go in and talk about what happened to them, and why they were arrested for prostitution, in front of their potential employer."

As for Maina, she doesn't see her record as a stain on her character. She knows she was coerced into sex trafficking—and that the acts that led to her arrests don't define her. "It's not something that I'm proud of, but I don't wear it as a scarlet letter," she says, "because it made me the woman I am today."

That woman is a college graduate and a mother. Her daughter Ja'naya has a radiant smile and likes to wear her hair in two puffy pigtails. She was born with developmental delays that prevented her from speaking until age four, but has made strides in her school's special education program.

Maina has been clean for 10 years. She refuses to take prescription painkillers for her back spasms since she worries they would lead her, again, down the dark road of addiction. She won't even pop an Aspirin. Just a couple of Benadryls at night to help her fall asleep.

Maina often has trouble sleeping—she suspects it's because her body got used to working all night. It's the only holdover from her old life, and she's working on shaking that, too.

*Names have been changed.

Maxine Joselow is a journalist based in Washington, D.C. whose work has previously appeared in Forbes, Washingtonian magazine, and Inside Higher Ed. She graduated from Brown University with honors in nonfiction writing.

-

Let's Go, PPG, Fans! A New Peacock Series Starring the 'Love Island USA' Season 6 Cast Is Coming Soon

Let's Go, PPG, Fans! A New Peacock Series Starring the 'Love Island USA' Season 6 Cast Is Coming SoonWe're already clearing our summer schedules for 'Love Island: Beyond the Villa.'

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Why Princess Diana Didn't Move to America

Why Princess Diana Didn't Move to AmericaThe late royal's friend opened up about the princess's American dream.

By Kristin Contino

-

Anne Hathaway Doubles Down on Luxury's Favorite Neutral

Anne Hathaway Doubles Down on Luxury's Favorite NeutralShe painted herself in the timeless hue.

By Kelsey Stiegman

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan

-

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein