Senator Tammy Duckworth Doesn't Want Her Daughter's Birth to Be News Anymore

"It says something about where our country is, especially in relation to other developed industrialized nations, that this is such big news."

Senator Tammy Duckworth is used to breaking barriers. An Iraq War veteran who chose to serve as a helicopter pilot because it was one of few combat jobs open to women, she was the first female double amputee from the conflict, after her legs had to be amputated when a helicopter she was copiloting was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. Duckworth went on to become the first disabled woman elected to Congress, in 2012. (She’s also the first Asian-American woman elected to Congress from Illinois and the first member of Congress from any state to have been born in Thailand.) Last year, she defeated incumbent Republican senator Mark Kirk to win a seat in the U.S. Senate, making her the second Asian-American woman in the legislative body.

And she’s not done achieving milestones. This spring, Duckworth, 50, became the first senator to give birth while in office, an occasion that forced the chamber to get with the times. On April 18, senators voted unanimously to allow infants on the floor during votes, reversing a rule that prohibited family members. That same day, in yet another historic first, Duckworth brought her 10-day-old daughter, Maile Pearl Bowlsbey, as she voted against confirming James Bridenstine as NASA’s next administrator. (He was confirmed 50–49.) This month, as Duckworth returns to work full-time, we speak with her about the buzz her pregnancy generated, paid maternity leave, and the age-old question of “having it all.”

Marie Claire: Are you surprised by how much attention your pregnancy received?

Tammy Duckworth: People have been very supportive and very kind, but what bothers me about it is that it is news. It shouldn’t be news; it should just be a snoozer of a thing: “Okay, she’s going to have a baby.” But it says something about where our country is, especially in relation to other developed industrialized nations, that this is such big news. We’ve got to get to a point where it doesn’t raise eyebrows to have someone give birth in office. Just like it shouldn’t raise eyebrows to have a woman be a senator or a woman in the cockpit or a woman in the boardroom. We’re not there yet, unfortunately.

MC: A lot of women, when they have kids, are asked how they'll balance work and motherhood—the common refrain about "having it all."

TD: The fact that I’m having a baby at 50 shows you can’t have it all. The reason [I had my kids later in life] is I made the choice early in my career that I don’t want other women to have to make. When I was in my 20s and trying to rise through the ranks of the military, I knew if I took time off to get pregnant and raise my children, it was going to affect my career. When they’re climbing the ladder in corporations or the government or the military, so many young women have to make this decision. They go on the mommy track—whether or not they want to, they’re sort of forced into it—because we don’t have the structures in place to support them. So they end up where I am. One day you wake up and you’re 40 years old and you think, Oh my gosh, what happened to my opportunity to have children? Luckily, I have the resources and have been fortunate enough to find a doctor who helped me have children in my late 40s and early 50s. But it took some time. I was 46 when I had my first child [Abigail, born in 2014], and I don’t want that for anyone else. I want people to be able to do both. But certainly, for me, I don’t have it all. I wouldn’t be in the situation I am in right now if I did.

MC: Did you do In Vitro Fertilization?

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

TD: I did do IVF. My husband and I ended up having to pay for IVF out of pocket because it was not covered by the Department of Veterans Affairs. I am working to change that to make sure we cover fertility treatments there.

MC: How did you decide how much leave to take?

TD: I cannot technically take leave because if I were to be under the status of “Leave,” then I would not be able to vote. I need to represent the people of my state, so I decided to take time to be with my daughter and curtail my duties down to the minimum, which is key votes and sponsoring legislation. I chose to have my daughter in Washington, D.C., instead of back home in Illinois so that I can be here.

People will say, 'Why don’t you leave your daughter with a caregiver?' My daughter needs to be fed."

MC: Why was it important to change the rule to allow you to bring your daughter to the Senate floor?

TD: Because, technically, I could not otherwise bring her to the floor, which means I wouldn’t be able to vote because I have to physically be on the floor to vote. There are people who will say, “Why don’t you just leave your daughter with a caregiver?” I could do that, except there are times when we have what we call a votarama, where we’re voting for 10 to 12 hours straight. And my daughter needs to be fed.

MC: Are you planning to breastfeed on the Senate floor?

TD: I’ll do whatever I need to both do my job and take care of my daughter. That’s what most moms and dads would do. The rule change also allows a male senator to bring his newborn onto the floor if he wants to bottle-feed.

MC: The U.S. is one of the four countries that don't offer paid maternity leave, and there are several plans in place to change that. What do you think of Ivanka Trump's plan, which would allow parents to draw from social security to fund leave?

TD: I would like to see her follow up on something other than just issuing press releases. The bill I’m cosponsoring is Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s [D-NY] bill. It’s based on kind of an insurance model, where you would contribute the equivalent of $2.50 a week and it would provide 12 weeks of paid family leave. And the employer would pay $3 a week. It’s very reasonable, it’s self-directed, it’s people helping themselves, and it just makes sense. Not having universal paid family leave is an economic detriment to our country. We can’t compete on a global scale for top talent because why would they stay here? Why would they not go someplace else, like Scandinavia or England, where there’s paid family leave and child-care support? And then we lose out.

MC: Are there any other policy changes you're looking at in light of your daughter's birth?

I’ll do whatever I need to both do my job and take care of my daughter.

TD: One that is on the cusp of becoming a law is my Friendly Airports for Mothers (FAM) Act. That legislation came about with the birth of my first daughter, when I was traveling back and forth to Illinois every week. I found that there was no safe, clean place for me to express breast milk in airports. The FAM Act would require all medium and large airports, which would be over 90 percent of the airports in this country, to provide safe lactation rooms for moms.

MC: That makes the case for why we need more women in political office: You realized this was a problem for women—something a male legislator may not have noticed—and have the power to change it.

TD: Exactly!

This article originally appears in the July issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

Kayla Webley Adler is the Deputy Editor of ELLE magazine. She edits cover stories, profiles, and narrative features on politics, culture, crime, and social trends. Previously, she worked as the Features Director at Marie Claire magazine and as a Staff Writer at TIME magazine.

-

The "Frightening" Easter Prank William Played on Eugenie

The "Frightening" Easter Prank William Played on Eugenie"Prince William has just stood on a chair and bitten the mouse's head off."

By Amy Mackelden

-

A Resurfaced Photo Reveals Charlotte's Royal Lookalike

A Resurfaced Photo Reveals Charlotte's Royal Lookalike"The Spencer genes are so strong."

By Amy Mackelden

-

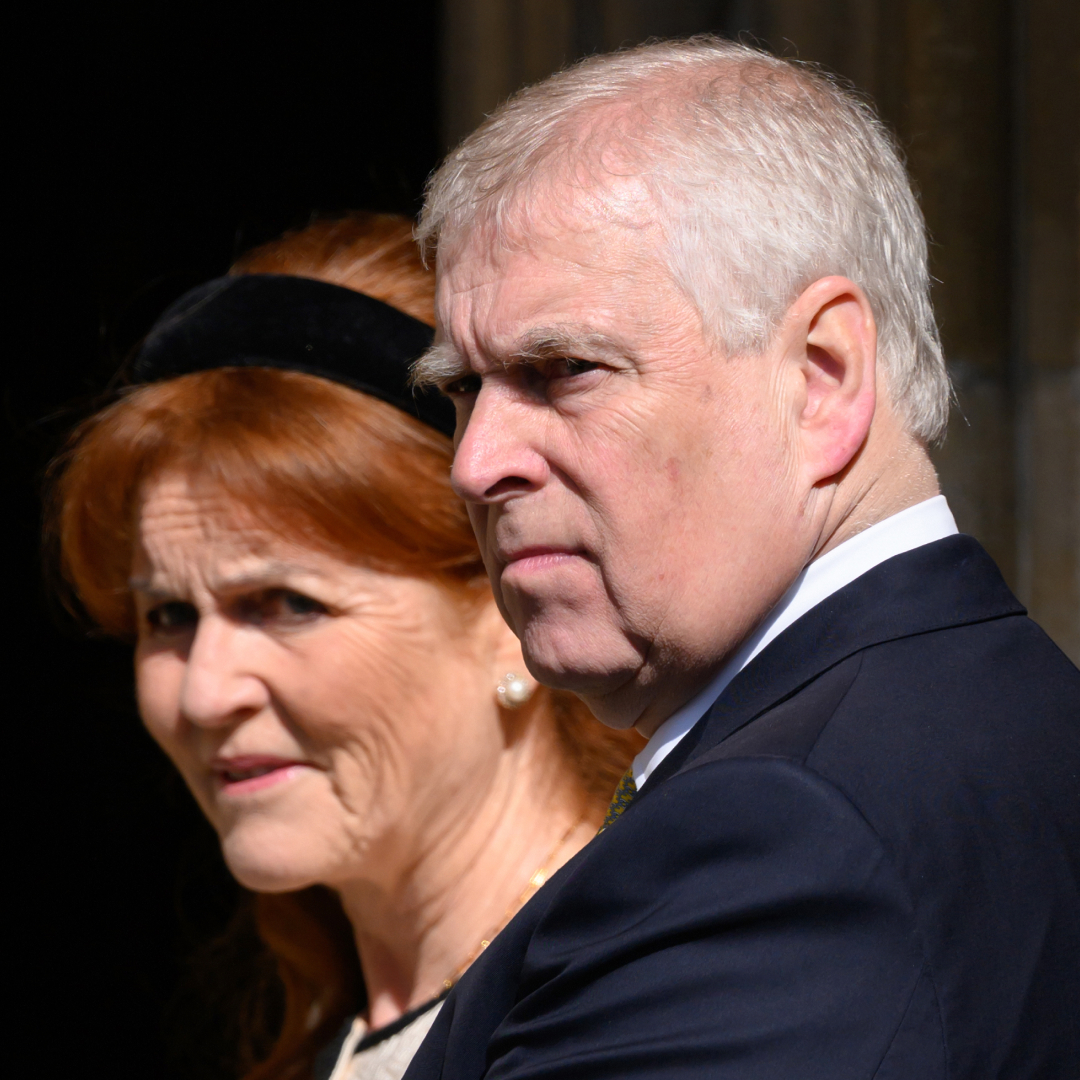

Why Prince Andrew Attended Royal Family's Easter Service

Why Prince Andrew Attended Royal Family's Easter ServiceIt was previously alleged King Charles's "patience was wearing thin" with his brother.

By Amy Mackelden

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

What's at Stake in the 2022 Midterm Elections

What's at Stake in the 2022 Midterm ElectionsWith abortion rights, democracy, and many more critical issues on the ballot, there’s no room for apathy this election cycle.

By Rachel Epstein

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

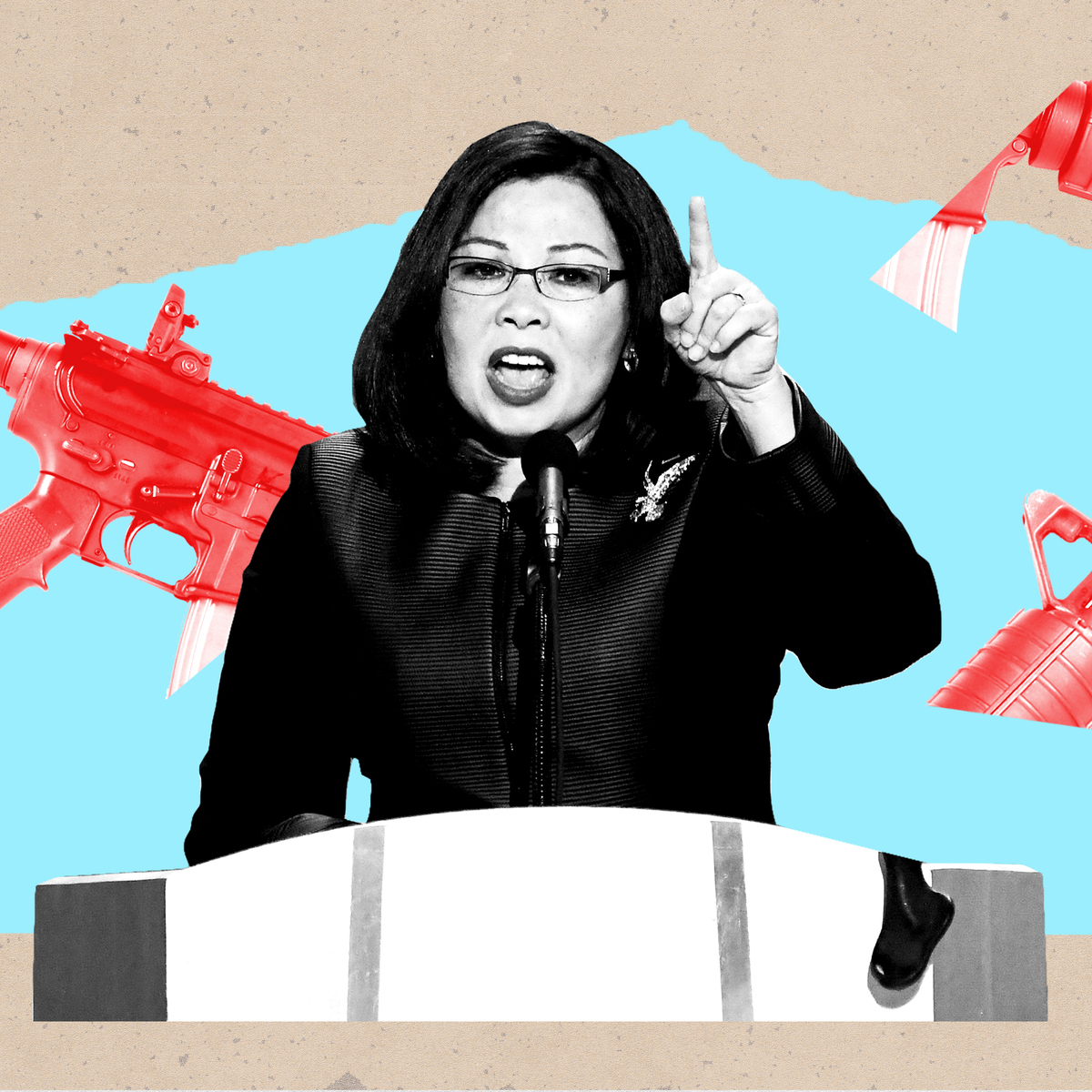

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

This Bill Wants to Stop Anti-Abortion Groups From Getting Your Private Data. Period

This Bill Wants to Stop Anti-Abortion Groups From Getting Your Private Data. PeriodPost-Roe period tracking apps and search history suddenly have serious implications.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio