What Happens Now for Immigrant Kids Separated From Their Families? Here’s What We Know

Most of the options are heartbreaking.

After weeks of hearing his zero-tolerance immigration policy compared to Nazi Germany, President Trump signed an executive order ending the separation of migrant families in detainment on Wednesday. But what will happen to the over 2,300 kids still separated from their families and being held throughout the country? While attorneys and lawmakers parse out exactly how to read the executive order—on top of still trying to understand the initial separation policy and its implementation—there are still parents awaiting trial, unable to contact or get any information about their children.

It's largely unclear what happens next for migrant kids seeking to reunite with their families. There are several potential futures that may pan out, many of them heartbreaking. Here’s what we know so far:

How do parents go about finding their child once they’ve been separated?

That depends on what’s going on with the parent. Assuming they either won their case for asylum or posted bond while awaiting their immigration hearing, they should be able to start tracking down their child and seeking reunification. The problem is, finding their children can be tricky. Once separated from their families, kids are flown to Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) facilities all over the country, and there are few options parents can turn to when it comes to finding out which one they’re in.

“There are two 1-800 numbers—one with ICE [Immigrations and Customs Enforcement] and one with the ORR—and they should be able to help parents and kids and even people outside the system find each other,” Michelle Brané, director of the Migrant Rights and Justice program at the Women’s Refugee Commission, tells MarieClaire.com. “The problem is that those lines are overburdened, they’re busy, people can’t get through. And even when you do get through, it takes them a long time to get you answers and they might not call you back.”

If the parent is granted asylum, they should be given paperwork upon release that could help them reclaim their child. But again, the issue is with coordinating all of the groups necessary to make that happen, since right now ORR, Department of Homeland Security, Health and Human Services, and ICE all have their hands in the logistics of the zero-tolerance policy and parsing who knows what about whom is proving difficult.

“It’s almost like being your own Private Eye,” says Brané of the parents who have to track down their own children.

What happens to a child whose parent is deported?

If a parent loses their hearing or decides to willingly self-deport, there are a few options. First, a child can choose to deport with their parent, says Brané. Or, if the child is really young, the parent can make that call for them.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

But again, to do either of those things the parents first have to track their kids down, which can be a logistical nightmare (see the first answer). That’s how you end up with situations where kids stay in ORR centers, unaware that their parents have been deported and with the parents unable to track down their children.

Lastly and most heartbreakingly, a parent can choose to leave their kid in the U.S. and deport alone.

Why would a parent choose to leave without their kid?

To quote Somali-British poet Warsan Shire, because “no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.”

“A parent might say, ‘I don’t want my child to come back with me. I left a really dangerous situation and they will die there, so just leave them here,’” says Brané. “It’s a horrible decision to make as a parent, but they might say it if they’re leaving something really, really horrible.”

Many parents who immigrated illegally are forced to consider this devastating choice.

Will this experience deter parents from trying to reenter the country illegally?

The short answer is, no. Deterring immigration was supposedly the impetus for this level of inhumanity, but it probably won’t work.

Think about it: If you were a parent forced to leave your child in a foreign country while you were deported, without really knowing where they were or what was going to happen to them, wouldn’t you probably try to sneak back into that country to find them? “It’s the opposite of a deterrent,” says Brané. “It’s an incentive to come back and look for your child.”

Can a child get deported on their own?

Yes. Though they’re on separate legal tracks from their parents once separation happens, children also have to go before a judge, who may choose to allow them to stay or force them to go back to their country of origin. “We don’t just automatically let kids stay here,” says Brané. “They also have to apply for asylum or SIJ or special visas. If they lose, they get deported.”

About half the time, a child will be assigned an attorney who can help them plead their case and file the appropriate documents to apply for asylum or a special visa. The other half of the time, they’re on their own, leading to surreal situations in which a five year-old may have to represent herself in court. John Oliver did a thorough segment on how the system got to this point:

What happens to children who stay in the system?

Sometimes families try to immigrate because they already know someone in the U.S. If a parent is deported, the children can theoretically be released to those people, but it only works if the person is documented. Not only does ORR typically avoid leaving kids with undocumented guardians, but plenty of would-be guardians don’t want to risk being deported if they go to pick the child up at a center. That leaves a lot of kids in detention centers without anyone to come get them.

This is where it gets a little more complicated. Though they will often be put in a foster care-like special system, legally a child can be kept in an ORR center indefinitely, says Brané. If that’s the case, they’re stuck at the center until they turn 18.

What happens if a child placed in a facility stays there until they’re 18?

If they hit age 18 while in a center and haven’t resolved their immigration status, ICE can retrieve them and put them in an adult center, says Brané. That means that, after what could be years in the system, immigrant kids could still get deported back to their country of origin.

Is detention the only option for migrant families?

Though the new executive order says families will now be kept together, detaining immigrants awaiting trial is hardly the only choice the government has. According to Brané, one effective alternative to incarceration is just making sure immigrant families give the address where they’ll be staying while they await trial.

In fact, the U.S. used to have a program that was 99% effective at making sure immigrant families stayed in the system while awaiting their court date, says Brané. “There was a program called the Family Case Management Program—FCMP—that we advocated for the government to use for a really long time, and they finally implemented it in 2016,” says Brané. As part of the program, families were given a case worker who would make sure they knew when and where their ICE appointments and court dates occurred, checked up on them at their given address, ensured their kids were enrolled in school, and even gave them bus fare if they couldn’t afford to get to their appointments. “Everybody showed up for their appointments and for court, and some families even decided to leave the country willingly,” she says.

Not only that, but FCMP was cheap to implement. “That program was $35 a day per family,” says Brané. “Compare that to the thousands of dollars spent on separating families and keeping them in custody.” What happened to that extremely effective and humane program? The Trump administration shut it down, citing budget issues.

What nonprofits are helping this exact cause?

The Women’s Refugee Commission monitors conditions in detention centers and fights for legislative and policy changes, among other things. Here’s their link to donate.

Kids In Need of Defense (KIND), which provides pro bono attorneys to represent children in immigration cases, receives donations here.

And there's Al Otro Lado, which provides direct legal support for migrants and refugees. Here's that link.

And here’s a list of four things you can do right now to help immigrant kids.

Cady has been a writer and editor in Brooklyn for about 10 years. While her earlier career focused primarily on culture and music, her stories—both those she edited and those she wrote—over the last few years have tended to focus on environmentalism, reproductive rights, and feminist issues. She primarily contributes as a freelancer journalist on these subjects while pursuing her degrees. She held staff positions working in both print and online media, at Rolling Stone and Newsweek, and continued this work as a senior editor, first at Glamour until 2018, and then at Marie Claire magazine. She received her Master's in Environmental Conservation Education at New York University in 2021, and is now working toward her JF and Environmental Law Certificate at Elisabeth Haub School of Law in White Plains.

-

Before Lisa Jewell's Most Highly-Anticipated Thriller to Date Hits Shelves, We Ranked Her 10 Best Books

Before Lisa Jewell's Most Highly-Anticipated Thriller to Date Hits Shelves, We Ranked Her 10 Best BooksFew do page-turners quite like her.

By Nicole Briese

-

The 'You' Season 5 Cast Features People From Joe's Past, a New Love Interest, Madcap Twins, and More

The 'You' Season 5 Cast Features People From Joe's Past, a New Love Interest, Madcap Twins, and MoreHere's what to know about the star-studded final installment of the Netflix hit.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

These J.Crew Sale Finds Basically Packed My Suitcase for Me

These J.Crew Sale Finds Basically Packed My Suitcase for MeI'm ready for my next vacation.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich

-

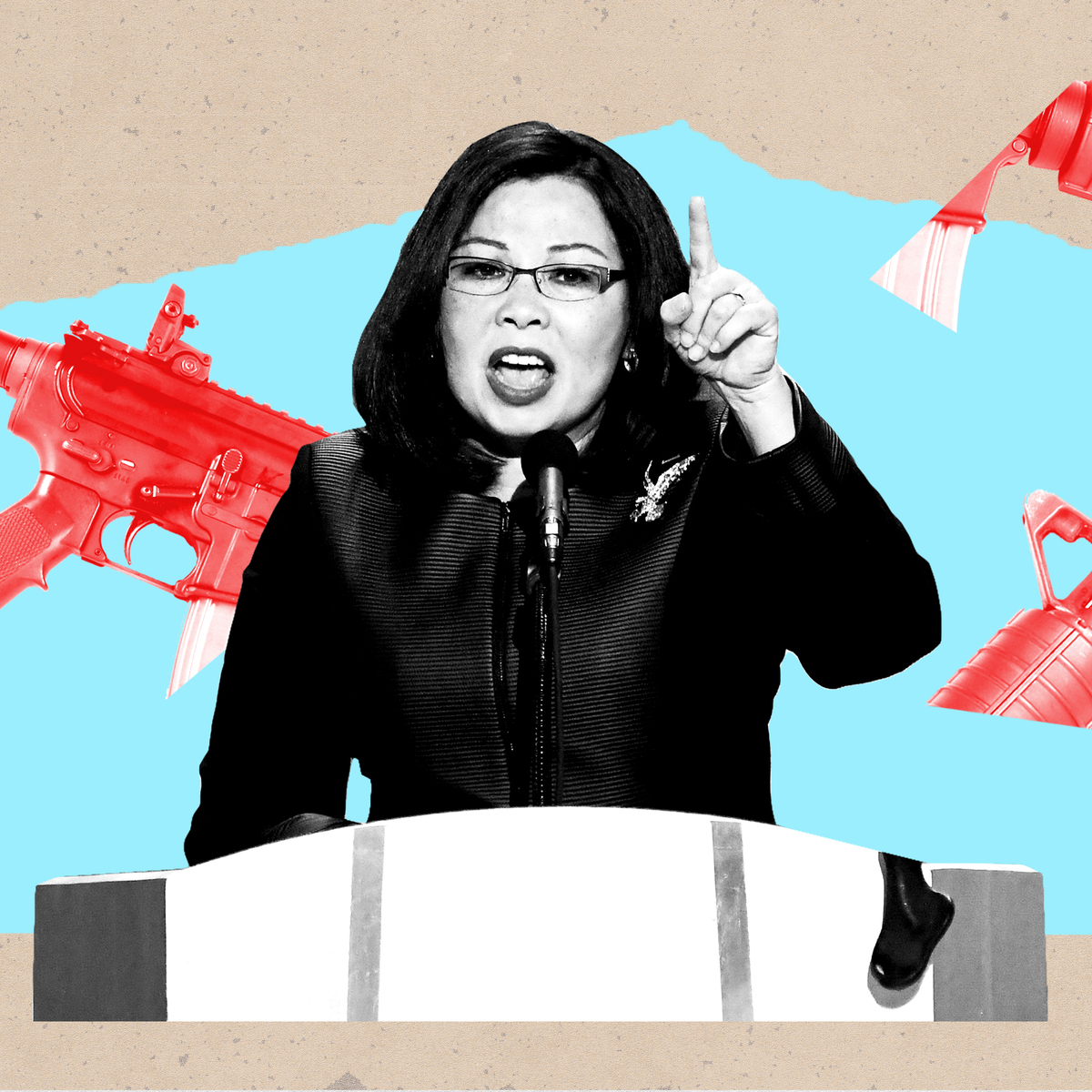

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan

-

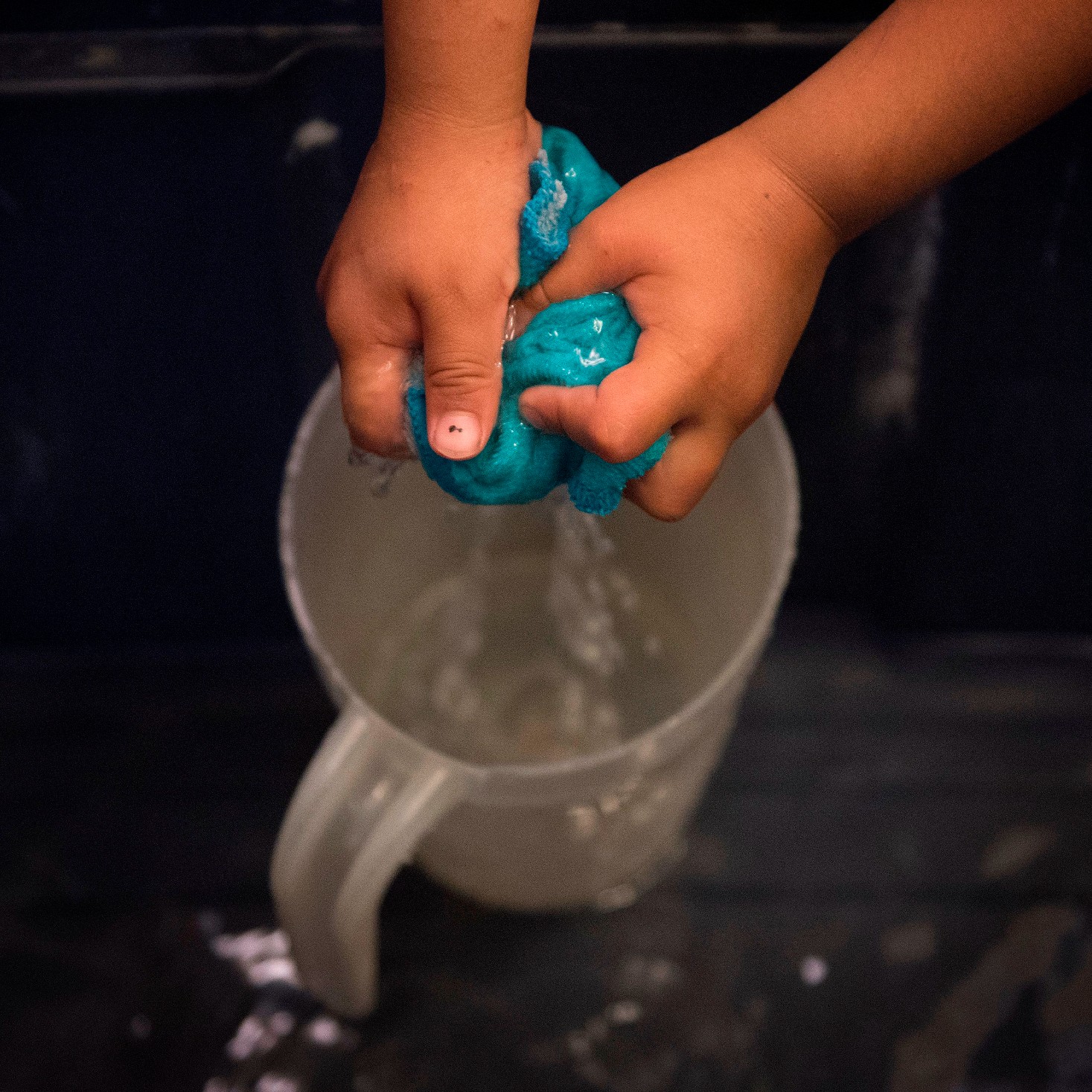

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein