Krishanti Vignarajah Wants to Be the First Female Governor of Maryland

She's the daughter of immigrants and a new mom.

People like to tell Krishanti Vignarajah she has a lot of nerve. She’s never held public office, she has a baby less than a year old, and, here she is, at 38, vying to be the first woman in history to be governor of Maryland. “So many people told me not to run, or they told me to run for a lesser office,” she says as she walks through the Bethesda Farm Women’s Market in Maryland on a breezy September morning, chatting with shoppers and vendors while her husband, Collin O’Mara, hangs back with their 3-month-old daughter, Alana, in his arms.

O’Mara is CEO of the National Wildlife Federation (America’s largest wildlife conservation organization), but today he’s on baby duty. “Collin was actually the biggest proponent for me running,” says Vignarajah, who has a friendly smile and a politician’s gift of listening with her entire body. To talk with Vignarajah is to feel not so much heard as absorbed. “After watching President Trump come to power, we both felt that there was too much at stake for me not to.”

Having spent five years working for the Obama administration (as policy director for Michelle Obama, she spearheaded Let Girls Learn, an international coalition that helps girls complete middle and high school), Vignarajah found it hard, she says, to watch as “President Trump reversed or threatened to reverse everything from our efforts on climate change to girls’ education to bipartisan issues like labeling on food so parents know exactly what their kids are eating.”

RELATED STORY

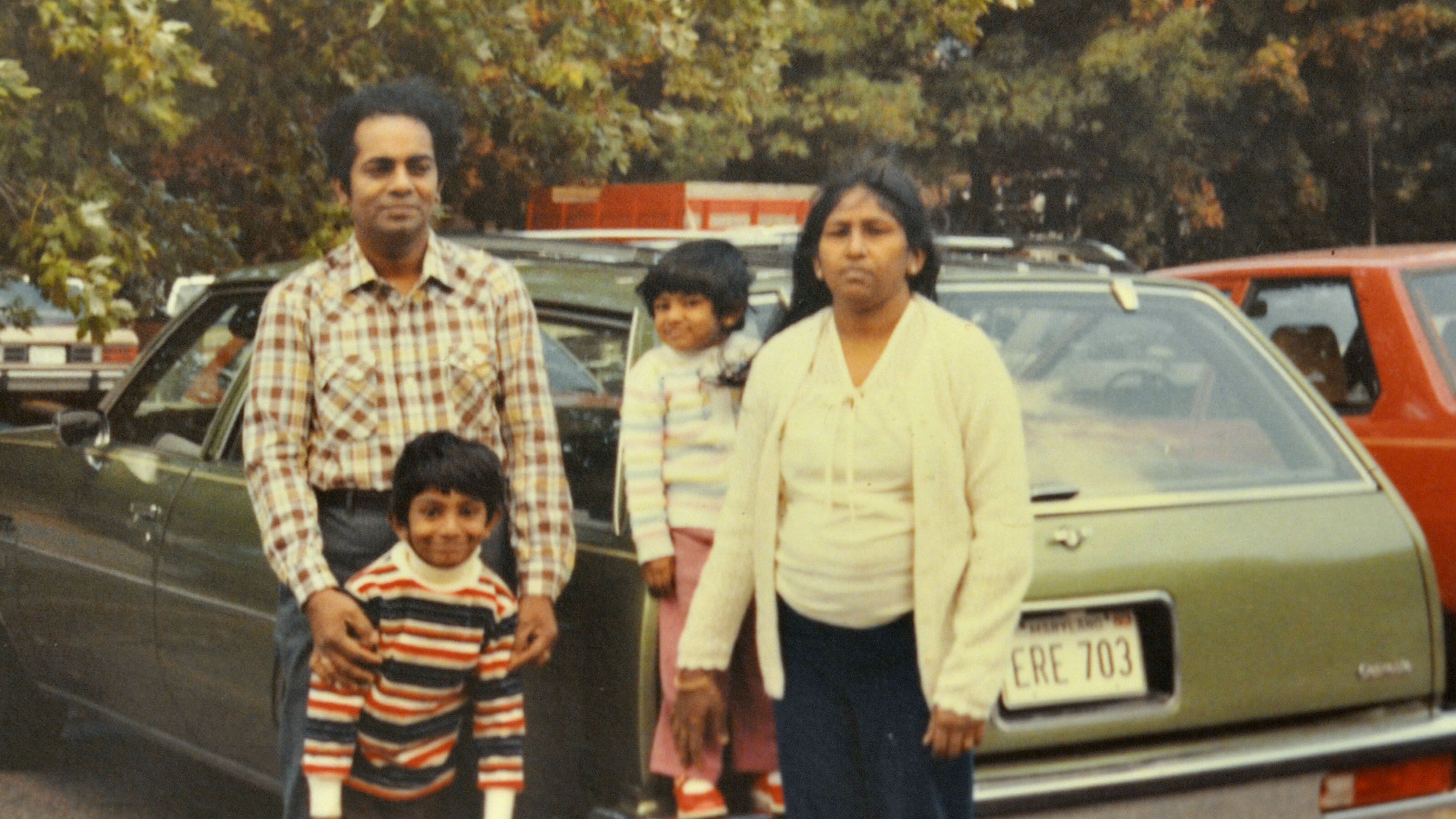

But Trump’s rise to power hit her on a deeply personal level as well. As the child of Sri Lankan immigrants who fled that country’s impending civil war in 1980 with $200 when she was 9 months old, Vignarajah is, as she likes to say, “Donald Trump’s worst nightmare.” Her parents were public school teachers. She grew up in a basement apartment in the Baltimore suburb of Woodlawn and attended public schools from kindergarten through high school before heading to Yale, and then Yale Law School—an immigrant daughter who excelled as a direct result of public education programs currently disappearing in Maryland.

Under her watch, Vignarajah says, education will come first. “I lived the American dream that a lot of us worry is slowly fading. My daughter is growing up in this world, and I’m worried that it’s going to hell in a handbasket,” she says, weaving her way through the stalls of zinnias and sugar snaps, asking questions and listening as vendors tell her their problems. A local farmer complains of skyrocketing operating fees and land prices. A jewelry seller who immigrated from Calcutta 25 years ago tells a tale of her husband being harassed in the wake of Trump’s election: “What’s happening in this country is why we left India in the first place.”

“One of the ways that we fight back is to show that a Democratic immigrant woman can be elected.”

On the way back to the car, Vignarajah says quietly, “I can’t tell you how many people tell me stories like that. And our governor just stands by in silence.” Historically, Maryland is a blue state, with Democrats leading two to one, but current governor Larry Hogan is a Republican. Under him, the Maryland Vignarajah knew has changed. “We have always led the country in terms of education, having a thriving economy, and protecting our natural resources, and all of that has been questioned or threatened by Governor Hogan’s leadership,” she says. “The opportunities I had growing up would not exist if we continue on the path we’re headed down.” With her choice of former Baltimore Teachers’ Union president Sharon Blake—an African-American woman and lifelong teacher—for lieutenant governor, Vignarajah’s becomes the first gubernatorial ticket in history to include two women of color.

Since Trump was elected, a whole lot of women have decided to run for public office: 423 women are planning to run for the House of Representatives— the highest figure in American history—52 for Senate, and 78 for governor (at press time.) But in Maryland, the case is particularly stark. All four elected executive seats and 10 seats in Congress are held by men. “That has to change,” says Vignarajah. “This past year, folks have awoken in ways that I’ve never seen before, but it’s what we do with this moment that matters.”

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Vignarajah had announced her campaign a day earlier at the modest Saint Agnes Apartments complex where she grew up, exactly the kind of economically depressed area she says has suffered under Hogan’s leadership with his cuts to public school funding. She herself attended the magnet program at Woodlawn High School, and, along with her older brother, Thiru (a former Maryland deputy attorney general currently running for Baltimore city state’s attorney), spent much of her free time at Enoch Pratt Free Library studying, using the computers, and soaking up the free air conditioning that their parents couldn’t afford at home.

“I’ve watched the state’s education ranking fall from first to sixth,” she says. “I’ve watched him cut funding from the neediest public schools. For him it’s just a line item, but I’ve lived it.” Asked why she decided to run for governor her first time out, Vignarajah says, “There’s something about being the antithesis. One of the ways that we fight back is to show that a Democratic immigrant woman can be elected governor. In a state where the wisdom is ‘No man can beat Larry Hogan,’ well, I’m no man.”

Indeed, she’s not. In November, Vignarajah was the first candidate to roll out a specific sexual harassment and violence policy in the wake of the #MeToo movement. Working with Ashley Judd, she crafted a detailed proposal that would create an Office of Sexual Harassment and Violence in Maryland, which addresses a host of issues, from requiring disclosure of a history of sexual harassment and violence for anyone seeking public office or state funding to supporting survivors and ending Maryland’s rape-kit backlog. “Krish and I spent a lot of time talking about how she would govern,” Judd says. “I learned that male rapists still have paternity rights in Maryland, and when I found out she was willing to take that on, I wanted to get involved. She’s a very gutsy leader.”

In some ways, Vignarajah seems like a born politician. Her friends have always teased her about how driven she is. She was the captain of the Division III tennis team at Yale and won pretty much every academic prize you can think of while she was there; she generally sleeps only three or four hours a night. “I get very impatient and anxious if I’m not in motion,” she says.

“I am trying to create a world in which being a mother is not an obstacle.”

But Vignarajah didn’t grow up dreaming of public office. Instead, she worked hard at things she cared about and trusted that the work would lead her where she needed to go. “My approach, whenever I consider doing anything in life, is to ask myself: Is it something I think is important to do? And, Is it something I’m passionate about?”After the Obama administration left the White House, Vignarajah—newly married and pregnant—launched a sustainable-development consulting firm called Generation Impact, and started giving keynote speeches around the country. “Afterward, people kept coming up to me saying, ‘Why aren’t you running?’” says Vignarajah, who gave the 2017 commencement speech at Hood College when she was eight and a half months pregnant. “I looked down and couldn’t see my feet, but then I realized that that was exactly why I should be running.”

Folks in Washington seemed to agree with her. After progressive strategist Liz Jaff saw Vignarajah deliver a keynote speech at the Western Maryland Democratic Summit in April 2017 (in the middle of Vignarajah’s third trimester) she walked up to Vignarajah’s husband and told him, “You’re not gonna like me in five minutes, and you’re going to hate me in five months.” Jaff, who understood the grind of the campaign trail, had been looking for a woman to run for governor in Maryland. Vignarajah recalls, “She said, ‘Watching you, I thought, I just saw the only woman who can beat our current governor.’”

Of course there were naysayers telling her that stepping up was a terrible idea. “A lot of people said, ‘You just had a child. Is this the right time?’” she says as she strides across the lawn at our next stop, Betamore—a tech startup and entrepreneurship incubator in Baltimore’s Federal Hill—with Alana on her hip. “But for me, it is the best time. I’m not trying to make a point by running, but I am trying to create a world in which being a mother is not an obstacle to going back to school, like my mom did, or trying to make partner at your firm, or running for office.” (In a campaign ad released in March, she breastfeeds Alana on camera.)

RELATED STORY

Within 24 hours of launching her campaign, Vignarajah says she received more social media attention than “all the guys combined.” People came out in droves to hear her speak. Meryl Streep donated to her campaign. (So did Mario Batali, and after the sexual harassment allegations against him came out in December, she used his donation to fund a symposium on sexual misconduct at Johns Hopkins.)

When it came to figuring out how to run a campaign, Vignarajah reached out to political veterans. Barbara Mikulski, the former Maryland senator, provided a crucial idea. “She said, ‘You need a MOM—someone in charge of Messaging, someone in charge of Organizing, and someone in charge of Money.’ That was really good advice.” But she’s frank about the difficulties of going first, including how to assemble a staff. “There are exceptionally loyal people who are campaign veterans, but some of my best people have never worked on a campaign before,” she says. “A good friend of mine who ran for governor said, ‘Be prepared to be disappointed by close friends and amazed by strangers. There are folks very close to you who you think will be there who aren’t, and there are the folks you meet along the way who become invaluable to the campaign.”

She admits that the learning curve has been steep. “I feel like I’m running a think tank, a company, and a PR firm right now,” she says, laughing. “Basically I’m running a conglomerate.” Also, she’s had to teach herself how to fundraise. “I did it in the Obama administration, but I find it much easier to pitch an initiative than to ask people to invest in me.”

“Thick skin is something you know you’re going to need going in.”

Also part of the job has been watching her fellow male candidates welcome one another to the race while pointedly ignoring her. “I do not play the gender card normally, but it stung.” And then there are the trolls. “People say horrible things on Twitter,” says Vignarajah. “They say, ‘What’s she gonna swear in on, the Kama Sutra?’ People suggest I’m an illegal immigrant, that I’m not eligible to run for office because I voted in D.C. while working for the Obamas. Thick skin is something you know you’re going to need going in, and I’m lucky—I don’t really get fazed by the chatter, but I do get affected by the fear that someone in my family might see something a troll writes. When someone makes a racist or sexist comment, it makes your blood boil.” (Addressing those carpetbagging claims, Vignarajah responds: “With a 3-month-old, I’m not going to throw my hat in the ring without doing my due diligence. We’re good.”)

Vignarajah’s up against six other Democrats in the primary on June 26—all men. Most notable are Prince George’s County executive Rushern L. Baker III and former NAACP president Ben Jealous (who has been endorsed by Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont). In a late-February Baltimore Forum straw poll, she came in second. “I’m an outsider, and I see that as an advantage in the sense that I think a lot of people are sick of the political infighting, the same old, same old,” says Vignarajah. “If you like the status quo, then you should vote for a regular politician.”

In the meantime, Vignarajah has her eye on the future. “On the day I launched my campaign, the little girl growing up in the apartment I grew up in told me that after meeting me, she’s considering a career as a politician. That’s the kind of thing I live for.”

This article originally stated incorrectly that Krishanti Vignarajah was the first woman to run for governor of Maryland. In fact, several women have run for the office previously, but none have won.

This story appears in the May 2018 issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands April 24.

-

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose"Princess Anne asked me if I'd have the surgery."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding Comment

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding CommentShe reportedly had lots of nice things to say, too.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down"

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down""Now he wants to do more and more and more. That's the problem."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman Last updated

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich Published

-

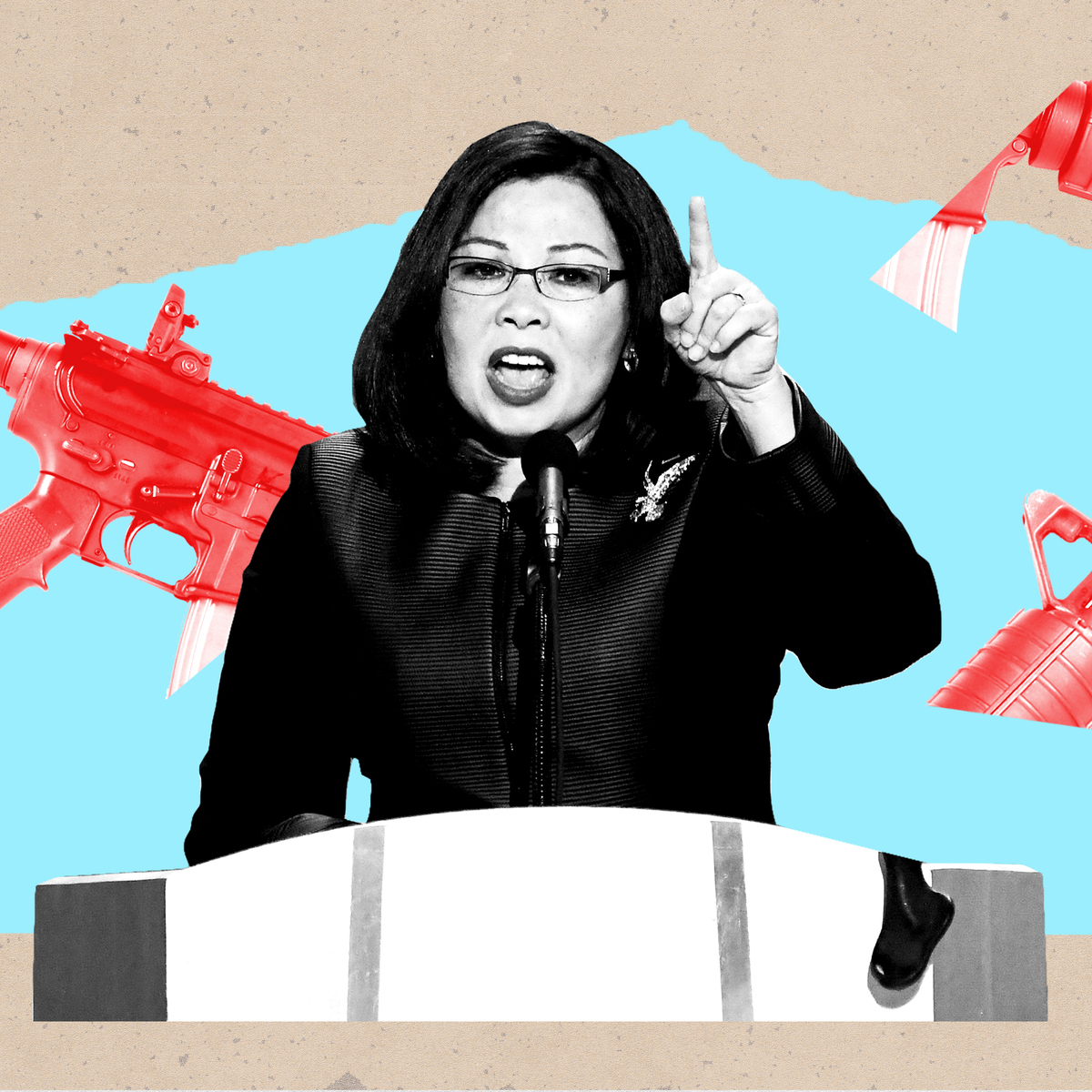

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth Published

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast Published

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan Published

-

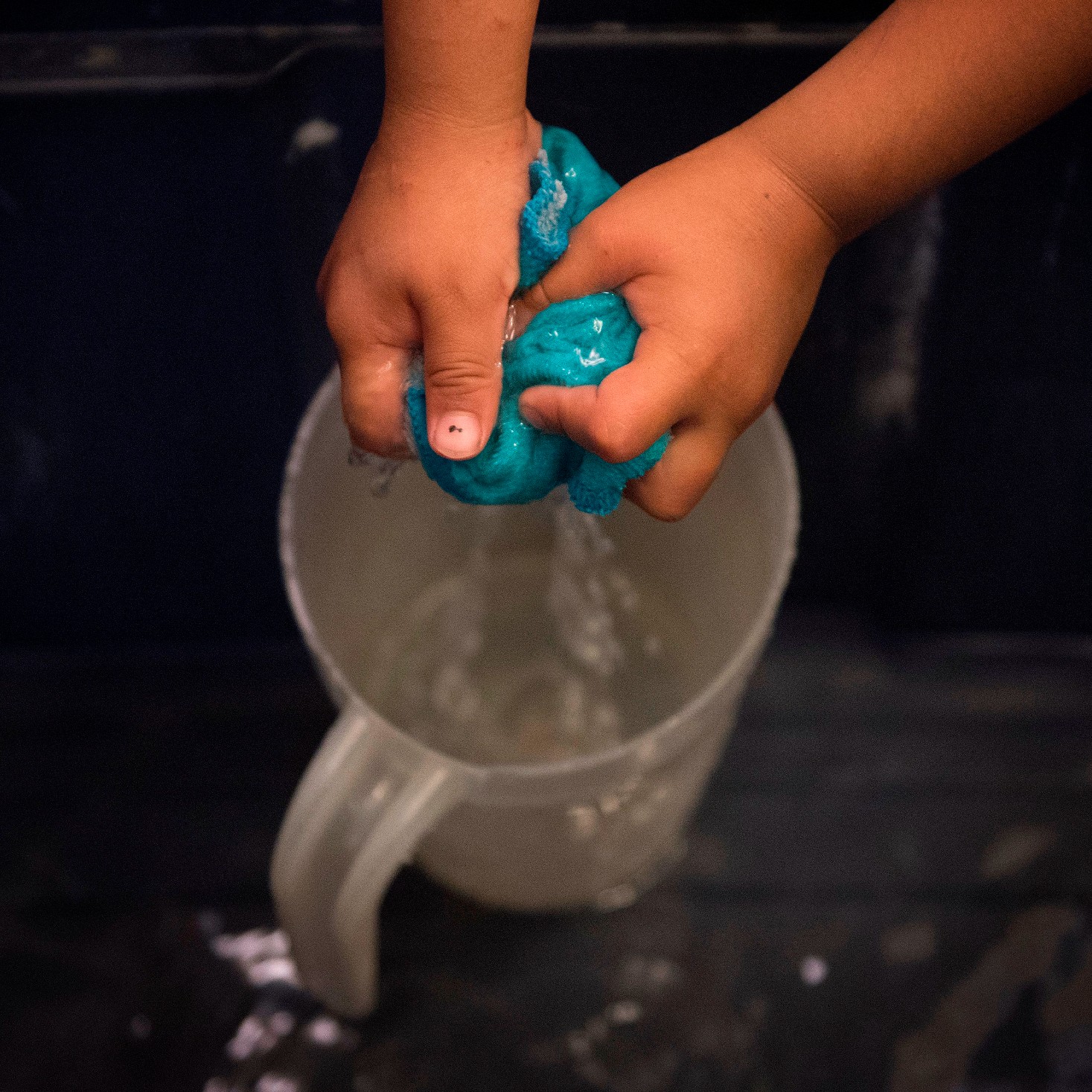

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein Published