Women and Guns

The Conflicted, Dangerous, and Empowering Truth

Beneath the surface of the guns discussion in America—one traditionally dominated by men—there's a complex world of females and firearms. Here, in the following 10 stories, we shed light on what often goes unseen: how women feel about, live with, and die by guns.

Chapter 1: The Statistics

The Real Landscape

MarieClaire.com partners with the Harvard Injury Control Research Center on a groundbreaking national survey of women's relationship with guns.

by Emily DePrang and the editors of MarieClaire.com

To read any set of statistics about guns in the United States is to read about men. Surveys typically assess gun ownership by household, meaning that if one person keeps a gun, his or her choice ends up representing the preference of everyone in the home. Counting by household silences the voice of whoever lost the debate, if there was one. And in the important and demographically lopsided issue of gun ownership, the silenced voice is usually a woman's.

It's a blind spot we're seeking to correct. MarieClaire.com has partnered with the Harvard Injury Control Research Center to study American women's beliefs, opinions, and experiences in relation to gun ownership and gun control, the results of which are published here for the first time. More than 5,000 people were surveyed—as individuals rather than households—and the results illuminate a nuanced landscape for women and guns. As you see in the infographics here (and the full survey and methodology here), it turns out that when women are allowed to speak for themselves, they have very different things to say.

According to our findings, 12 percent of American women own a gun. But nearly three times as many men own guns as women do, and male gun owners are more likely to carry their guns in public than female gun owners are—which means the large majority of gun-toting civilians are men. Generally, when a gun is part of an American civilian's life, whether locked in a bedside drawer or holstered to a stranger's hip, a man decided to put it there, and he will decide, moment to moment, how it should be used.

It's a disparity made all the more striking by the fact that 74 percent of the women we polled believe that men have a different mindset about guns than they do. Many attributed this to the fact that men are made more comfortable with guns from an early age, from toys to hunting, and that women aren't as often exposed.

It makes sense, then, that what a gun means to a woman is largely dependent on whether she has one. Only 20 percent of the general population of women believe that having a gun at home makes it a safer place—though the majority of gun-owning women do.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

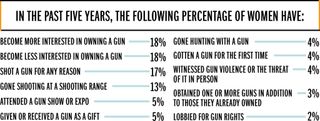

In a country tangled up in headlines about gun violence, rapes, and terrorist threats, women are on edge. While 49 percent of our female respondents report feeling more negatively about guns in light of recent shootings and terrorist attacks, fear for their personal safety has driven others to want to arm themselves—18 percent of the general population of women have become more interested in owning a gun in the last five years.

At the same time, our findings show that it is exceptionally rare for a woman to need to actually use a gun to protect herself—less than 1 percent of women report having used a gun in self-defense. For the majority of women, guns don't even top the list of preferred personal security measures. Home security systems, having a large dog, and taking a self-defense class were ranked higher by more respondents as ways to feel secure.

Of course, in many cases, what women fear most is the gun itself. Forty-seven percent of our respondents say that seeing a civilian wearing a holstered gun in public would make them feel less safe than they do now.

Most Americans favor stricter gun control, but women want it more: Sixty-two percent of women want stricter laws governing gun sales, versus 54 percent of men.

These women will be bringing their beliefs to the polls, and they expect the candidates to speak up before they get there: 63 percent of women surveyed want guns to be a major topic in the upcoming presidential election. Fifty-one percent of women want the next president to take action on guns, including tougher gun control, better background checks, and mental health screenings.

Though largely untapped by the political system to speak up on gun issues, American women want to be heard. The following story series aims to amplify their voices from all corners of the country. For the women you're about to meet, guns are their sport, their source of protection, their greatest fear, their biggest regret, their firmest belief. No matter their reason, it's time for American women to step up to the microphone.

Chapter 2: The Politics

Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina Lay Their Gun Beliefs Bare

The current and former presidential candidates make impassioned appeals from both sides of the aisle.

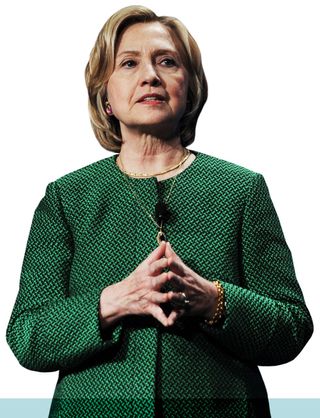

by Hillary Clinton

Not long ago, at a restaurant in Chicago, I sat down with a group of women who are members of a club no one ever wants to join. One by one, each held up a picture of a beloved child killed with a gun. Pamela Bosley's son was shot while standing outside of church before choir practice. Cleopatra Cowley-Pendleton's daughter was shot in a park in broad daylight just days after she performed with her marching band at President Obama's second inauguration.

I tried to find the right words to comfort and console. I fell short; there are no right words. Later I learned that in the time we were together, a 9-year-old was shot and killed just miles away.

America loses, on average, 90 people a day to gun violence—homicides, suicides, and terrible, tragic accidents. That's 33,000 deaths each year. Almost every person I've met who has lost a loved one to guns is like those mothers in Chicago. They aren't looking for sympathy. They just want an end to all these needless, violent deaths. They want to spare other families what they've endured.

It's time for the rest of us to show that same courage.

Too often, guns are seen as a male domain. But women care about guns, too. Plenty of women own guns. Plenty of women care deeply about their Second Amendment rights. And women have long been at the forefront of the movement to end gun violence in America, from Sarah Brady to Gabby Giffords to the mothers who've turned their grief into action.

Women aren't monolithic; our opinions about guns are as diverse as we are. But just about all of us can agree that far too many people are dying from senseless gun violence—and that we need to do something about it. Any serious conversation about guns has to take into account our voices and experiences—as citizens, mothers, survivors, and advocates on all sides of this debate.

"Women aren't monolithic; our opinions about guns are as diverse as we are."

The good news is that we already have consensus. Ninety-two percent of Americans support universal background checks. (So do 83 percent of gun owners!) So our challenge isn't finding common ground—we've already found it. Our challenge is getting politicians to listen to their constituents rather than the gun lobby.

As a former senator and a candidate for president, I have ideas for how we can reduce gun violence without compromising anyone's rights. We need comprehensive background checks that keep guns out of the hands of domestic abusers and other violent criminals. We need to do a better job of making sure gun dealers follow the law, and if they don't, we should revoke their licenses. We need to end laws that let the gun industry act without consequences and that shield them from liability. And we need to close legal loopholes that allow dangerous people to buy weapons without clearing a background check if that check isn't completed within three days. That courtesy isn't worth people's lives.

If Congress won't take these simple steps to save lives, we need to elect people who will. The gun lobby's stranglehold on Washington is ludicrous. It has to end.

And for that to happen, women have to decide that guns are an issue worth going to the polls for. We need to say, loudly and clearly, that we will choose candidates who support sensible gun reforms. We need to say that if you're on the wrong side of this issue, you will not get our vote.

Maybe someone you love has been affected by domestic violence, and you care about keeping guns away from abusers. Maybe you love hunting but think felons shouldn't be able to buy handguns. Maybe you're a mom who wants guns nowhere near your kids. Maybe you have a gun in your home for protection and went through a background check to get it and think there's absolutely nothing wrong with other people having to do the same. Or maybe you're just deeply concerned about a political system that can't get the most basic law passed, even as thousands of children die.

Whatever your reason, I hope you'll join me in insisting that ending gun violence is a priority in this election.

President Obama recently announced that he will take new steps to address America's gun violence epidemic. Like most Americans, I support President Obama's actions. But I worry about what will happen if our next president doesn't share his convictions. And beyond the presidency, we need officials at every level of government who'll stand with families, not the gun lobby.

For 20 years, I've been meeting people who have lost loved ones to gun violence. I've listened as survivors of mass shootings recounted nightmarish experiences. I've stood with gun owners as they pleaded for saner gun laws. I've watched the political debate shift and our national conversation evolve—often for the worse, but sometimes for the better. Change is possible. I believe that deeply. But it isn't inevitable, which means we can't give up. We can't become so cynical or heartbroken that we stop trying. We have to keep speaking out. And above all, we have to vote.

There is no more powerful corporate lobby than the gun industry. They fight like hell to get their favored politicians elected, and once elected, they fight like hell to keep them there. But you know what? They're no match for American women. We don't back down from a fight worth fighting.

I urge you to join this debate. Let it be known that gun violence is a women's issue—just like any issue that impacts millions of Americans. We care about this issue as women. We care about it as citizens.

And citizens vote.

by Carly Fiorina

How long have politicians been telling you that they want to do something about gun violence? How long have they exploited tragic stories to convince you to vote for them? And how often do they get into office and do nothing until the next election rolls around?

We can all stand in front of the cameras and decry violence. But year after year, politicians say one thing to you from their Twitter accounts while refusing to admit that they aren't enforcing the very same gun laws they say aren't enough.

We have a background-check system in place that is flawed and susceptible to human error—or in some cases that we're not using at all. Had it been used properly, that system would have prevented Dylann Roof from purchasing the gun that he used to murder nine people in a South Carolina church. It would have prevented Seung-Hui Cho from purchasing the gun he used to murder 32 people at Virginia Tech in the largest mass shooting in American history. Both times, it failed.

In 2010, the FBI reported tens of thousands of failed attempts by felons and fugitives to buy guns. The Department of Justice only prosecuted 44. The professional political class isn't enforcing the laws we already have—in fact, they're vilifying the issue to score points with you.

How many times have you heard that gun owners are the problem and that the NRA is evil? That all those Americans clinging to their guns and religion just don't get it? Whenever the political class uses gun violence to push their own partisan agendas, they prove once again that they are politicians—not leaders.

"The professional political class isn't enforcing the laws we already have—in fact, they're vilifying the issue to score points with you."

I support the Second Amendment not because I'm a hunter, or even a skeet shooter. I'm not. I've never had to protect myself, my home, or my family from an intruder—though nothing levels the playing field between a 230-pound man and a 120-pound woman like Smith & Wesson. I support the Second Amendment because it's our God-given right and our constitutional right.

I'm sick of being told otherwise. I bet you are too. But too many people in government are willing to give away our rights when it is politically expedient, when it makes for a good talking point, or when a consultant tells them it will poll well.

Gun violence is a problem that must be solved—but creating new laws that weaken our constitutional rights is not the answer. Our Founding Fathers designed a government that was supposed to work for the people, not in spite of them. But President Obama's new executive actions do exactly that. They undermine our legislative process, our Constitution, and the will of the people. He is working hard to enact something that Congress has rejected twice on a bipartisan basis. Unfortunately for him, that is not how the Constitution works.

(And even if you cheer the result this time, process matters. These same checks and balances you may decry for slowing down the process today will be the very thing you want in place the next time you disagree.)

So before we politicize this issue and pile on onerous regulations that infringe upon our constitutional rights and punish law-abiding citizens, I believe we must enforce the laws we have.

We need to take some commonsense steps. We need to prosecute the people who shouldn't have guns. We need to invest in mental health so we can tackle this problem at its root. We need to fix our broken systems and defend our unenforced laws.

But here's the real problem underlying this and so many other festering issues that only seem to get attention during election years: Our government has grown too big, too complex, and too corrupt. It is run by a professional political class that no longer serves you.

The highest calling of a leader is to unlock potential in others. The highest calling of our president is to restore a citizen government to this great nation. And at the core of that citizen government are women like you.

We need a proven, tested leader in the White House. He or she must be prepared to change the order of things because they haven't spent their whole lives in the system. We need a president of courage and conviction who will engage you to solve our nation's problems.

You know something is going desperately wrong in this country and it's on us to fix it. It is time to take our country back.

Chapter 3: The Victims

"The Last Time I Saw Her"

Six women from across the country open up about the sisters, daughters, and mothers they lost to mass shootings.

by Abigail Pesta, with photographs by Madeline Ziecker

Mary Kay Mace lost her daughter, Ryanne

The last time I saw my daughter, she had come home for a weekend from college. Her school was just a 45-minute drive from home, so my husband and I saw her pretty often. On that visit, we gave her a little bit of ribbing about her car—she didn't keep it very neat. It was like a rolling junkyard. She laughed and said, "Yeah, yeah, I know." Before she left, I gave her a hug and said, "We'll see ya, kiddo. Love you."

My daughter, Ryanne Mace, was killed in a mass shooting at Northern Illinois University on February 14, 2008, Valentine's Day. She was sitting near the front of her ocean-sciences class when the gunman burst in the room. She was 19 years old.

Ryanne was my only child. She loved offbeat humor: Monty Python, Stephen Colbert. She befriended all types of people from all walks of life—she had a soft spot for the underdog, the kids who weren't popular. She didn't think anyone should be an outcast. She was pursuing a degree in psychology because she wanted to counsel people face to face and help them talk through their problems. If she had known her shooter, she would have tried to befriend him.

On the day of the shooting, I was at work. My boss's wife called, saying there had been a shooting at NIU. My mind immediately went through all these protective things, like what were the odds that she was even on campus. I kept calling her phone. I finally reached one of her friends, who said yes, she was in that classroom.

We got in our truck and took off. We stopped at the hospital and talked to the first person we saw with a clipboard. Ryanne was not on the list of the injured. I thought, Thank goodness, she's not hurt.

A campus police officer asked us a lot of questions. We kept going back and forth because an unidentified victim had a tattoo. I kept saying, "Ryanne doesn't have a tattoo." Well, she did have a tattoo. We just didn't know.

Ryanne was a few months short of turning 20 when she died. For her birthday, my husband and I decided to take her ashes out to Oregon, where we lived when she was a little kid. On the way, we hit all these places she had visited and wanted to go again. We went to the Black Hills, Mount Rushmore, Devils Tower. We scattered her ashes in Oregon. Then we drove back a different route, through places she had never been. Here we were, forging a new path without her.

Jillian Soto lost her sister, Victoria

The last time I saw my sister, she was home late from school, eating dinner, just a typical evening. It was a couple weeks before Christmas, her favorite holiday. We talked about how it would be fun for the family to wear "feetie" pajamas for Christmas. I was getting ready to leave for a ski trip that night, so I finished packing and ran out the door. I never said goodbye, never thought twice about it.

My sister, Victoria Soto, was killed the next day, on December 14, 2012, in the classroom where she taught at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut. She was 27 years old.

My sister taught me everything—how to roller-skate, what to wear, how to straighten my hair. Growing up, I admired everything about her. I went to the same college as her, hung out with her and her friends, borrowed all her clothes. She was that person I called when I needed to know what to do about a boy.

We have a picture of her from before I was born: She was at Disney, looking at the flamingos, and you could just see the awe on her face. She started collecting flamingos: She had flamingo bedsheets, pictures, stuffed animals.

This past August, we opened the Victoria Soto School, an elementary school in our hometown of Stratford, Connecticut. There are pictures of flamingos in the main office, and the staff wears pink shirts.

In the days after the shooting, the world stopped and grieved with us. And then, the world started going again. But not for us. We were just going through the motions. That's what happens when you lose someone so suddenly, so unexpectedly.

That day took away so much from me—not just my sister, but my sense of security. Now I need to know where the exit is; I look for places to hide in large groups. The worst part has been watching my family fall apart. Vicki was my mother's firstborn. My mom is so heartbroken, and I can't fix it. I can't take away that pain for her.

Every time another shooting happens, I actually get physically sick. I feel like the walls are caving in. I can't breathe. When people tell me my sister is in a better place, I get angry. She was already in a good place. That school and the students—she called them her kids—were everything to her. She died doing everything she could to keep them safe.

This past September would have been my 27th birthday, but I've chosen not to celebrate being 27 because it means that I've outlived my sister. In my eyes, I'm still 26 and I'm just going to skip to 28. At the same time, I have made a resolution: I'm in control of my own life. I'm in control of my happiness. I'm getting that back. I'm going to honor my sister every day—I'm going to smile every day because that's who she was. She loved life. I have to do it for my sister, and for my family, and for myself, because I can't allow someone else to win this battle.

Reverend Sharon Risher lost her mother, Ethel, and her cousins Tywanza and Susie

The last time I talked to my moms, we discussed one of her favorite things in the world: perfume. As a mother of four girls, she would always spray my sisters and me for special occasions when we were kids. Then she would hide the bottle because she knew we would be spraying it all over the place.

This past June, she called and said, "Ooh, I smelled this Banana Republic perfume—I sure would like to have some of that." I said, "Ma, would you like me to buy you that perfume?" I bought a bottle, but I didn't send it right away.

It was delivered to her the day after she died.

My mother, Ethel Lance, was shot and killed in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015, along with two of my cousins, Tywanza Sanders and Susie Jackson.

My moms loved that church. She was a member for more than 40 years. She worked there as a sexton, keeping the church neat and clean, to make a little extra income to help my niece in college. She had such a work ethic.

Cousin Susie was a matriarch of the church, one of the oldest members of our family. If she saw you chewing gum in church, she would give you the stinky eye. My cousin Tywanza was a young man with an infectious smile, a big heart. He had such promise to be whatever he wanted to be.

When I heard about the shooting, a scream came out of me. To have three people taken out of your life is just overwhelming. It's only because of my faith and because of the faith of all the people in that church that I'm able to continue to walk, to continue to get out of bed.

My mom and I would talk at least three, four times a week. She would call me on Sundays; she would say, "Girl, Reverend Pinckney throw down today."

All my life, my goal was to make my moms proud of me. When I had an opportunity to preach in the Emanuel AME Church, well, I went in that church and turned it out. My mom sat in the front row, just crying.

Forgiveness is a process. I'm not there yet. Being without my moms, I don't have the chance to call her on the phone, to ask her how to cook gumbo, to sleep in her bed with her when I go home. But I know that one day, when I get to heaven, what a day it will be. What a day it will be when I get to be with my moms again.

Sandy Phillips lost her daughter, Jessica

The last time I heard from my daughter, it was late and I couldn't sleep. She was at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado with her best guy friend—they were at a midnight showing of The Dark Knight Rises. I was planning to visit her the next week. She texted me, "I can't wait to see you. I need my mama." And I wrote back, "I need my baby girl."

Less than 40 minutes later, she was shot six times. One bullet left a five-inch hole in the side of her face. That was July 20, 2012, and it feels like yesterday.

My daughter, Jessica Redfield Ghawi, was 24 years old. She had one semester left of college, where she was studying broadcasting and journalism. She wanted to be a sportscaster—she was so determined and tenacious. She was already respected by men who had been doing the job for many years. Actually, one of them—kind of a curmudgeon—told me that Jessi's passion had rejuvenated him, like she was a light being brought into the room.

She was planning to go to a job interview on July 21.

During the shooting, her friend called me from the theater. I could hear the screaming in the background. I said, "Where's Jessi?" And he said, "I'm sorry." When I realized she had been killed, I guess I started screaming, although I don't remember it. I don't remember much after that.

A lot of people say that when someone gets shot, the adrenaline kicks in and the person doesn't know what's happening. But Jessi did know. The first bullet hit her in the leg and she fell. She said, "I've been hit." The bullet went through that leg into the other leg. While she was falling, she was hit three more times in the abdomen. Her clavicle was shattered. She was screaming, "Someone call 911!" Then she was shot in the head.

It's the little things you miss the most. I miss her texting me pictures of her trying on clothes, or asking me what I think of a new haircut. I miss the way she flipped her hair, the sound of her heels as she walked up to the front door, the way she laughed—she was not a giggler, she was a belly laugher. All those littles.

Six weeks before the shooting that ended her life, Jessi had just missed another shooting at a mall in Toronto. Shots were fired in the food court just two minutes after she had left that same area with her boyfriend. It deeply affected her. She went home and wrote on her blog, "Every second of every day is a gift."

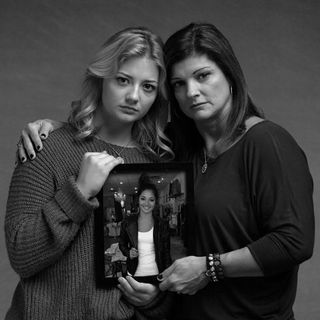

Ali Breaux (pictured here with her mother, Dondie) lost her sister, Mayci

The last time I saw my sister, she was home for a weekend to visit with our family. She was 21 years old, studying radiology in college. I was 15, getting ready to practice driving, and she was supposed to come with me. But she was scared to drive with me, and I don't blame her. My dad came instead. I really wish I could have had that time with her.

My sister, Mayci Breaux, was shot four days later, on July 23, 2015. She died while watching Trainwreck in a movie theater in Lafayette, Louisiana.

Mayci was always there for me through everything, giving me advice. She made me realize that things that seemed big were actually really small. She would say, "It's just high school—it's not that big of a deal." She would tell me not to feel sorry for myself. It made me realize: If you just sit around and feel bad for yourself, you're not getting anywhere. She helped me see the big picture. She built me up.

She also made me laugh. Growing up in the town of Franklin, Louisiana, we rode four-wheelers, jumped on the trampoline. We both loved to dance, too—ballet, hip-hop, jazz, lyrical. She especially liked hip-hop.

On the day she was killed, I was at a dance convention in New York. I was dancing when I suddenly felt this huge pain in my neck. I just kept pushing through, because that's what dancers do. Later, I learned that the pain had come at the same time my sister was shot.

I was in the hotel room that night when my mom came in, hysterically crying. She said Mayci and her boyfriend, Matthew, had been in a shooting. And that's when the shock hit. I just kept asking God, "Please, don't take her away." I couldn't see my life without her.

Late that night, we learned she was gone. I couldn't talk, really. I was just a statue until I got home. That's when I realized the things we used to do together were gone, like when I would come home on Friday nights and she would be there, and we would stay up late and talk. That's when I lost it.

Matthew was shot, but he survived. He told me that right before the shooting, Mayci had gotten a joke in the film really late, so she was laughing really loud, seemingly at nothing because the joke had passed. She had an infectious laugh. That was his last memory of her.

Back at school, I could feel the stares of everyone. I kept reminding myself that no one knows how this feels. I had to keep going because there was nothing else I could do. I joked around with people because that was my usual thing. Since Mayci was so hilarious, I didn't feel guilty for still laughing because she would want me to be myself.

I had a million moments with Mayci. But if I could tell her one thing now, I would thank her. If it wasn't for her, I would not have been this strong.

Jenna Yuille lost her mother, Cindy

The last time I saw my mom, we were cross-country skiing with her husband, up near Mount Hood in Oregon. It was two weeks before Christmas, and we took a bottle of champagne and hid it by a tree. Our plan was to go and dig it up for New Year's.

A week later, on December 11, 2012, my mother, Cindy Yuille, was shot and killed at the Clackamas Town Center mall in Portland, Oregon.

My mom was not a mall person. She was a total hippie mom: She loved her garden, loved being in nature. She backpacked, camped in the snow, loved going on hikes. She really cared about the Earth. To save trees, she sewed her own cloth gift bags instead of using regular wrapping paper. She worked as a hospice nurse, taking care of people in their homes as they were dying.

On that last ski trip, she asked if I was going to get a Christmas tree. I said no. I was 23 years old, and I felt busy and didn't want to bother. I came home from work that Monday and there was this little Christmas tree outside my door with a box of ornaments and lights. I knew it was from her. It was just the kind of sweet thing she would do. I called and thanked her. That was the last time I actually spoke with her, just a normal, "Hey, thanks, Mom." The next day, she called me in the morning, but I didn't pick up my phone because I was at work. She didn't leave a message, which was not unusual. I called her back a little later, and she didn't answer. The shooting happened that afternoon. I still think about that: Gee, I wonder what she was calling about. I'll never know.

I saw the news of the shooting on Twitter while I was at work. I called my mom. I don't normally do that kind of stuff, but I just figured I'd check. She didn't answer. I called the house and asked her husband, Robert, if he knew where she was. He said she had gone shopping. I knew that she would have gone to the mall—it was two weeks before Christmas, so it would make sense for her to be there. But, I figured, she's probably fine. There were thousands of people there. What were the chances? You never expect something like that to happen to you or your family. It took a whole year for it to sink in and actually become real.

In the weeks after the shooting, our mailbox was stuffed with cards from the families she had cared for. It was nice to know that so many people loved her.

Eventually we went back for the bottle of champagne, Robert and my little brother and me. The three of us went back to that same spot on the mountain where we'd been with my mom, and we tried to dig up the bottle. But we couldn't. There had been too much snow, and it was buried too deep.

Special thanks to Everytown For Gun Safety for their help with research and sources.

Chapter 4: The Gangs

The Rise of the Girl Gang

The new wave of women gang members aren't girlfriends on the sidelines. They're fighting their own violent battles on the street.

by Colleen Curry and Michelle Mulligan

In neighborhoods where buildings burn until they flame out and schools shut down forever, gun violence isn't a tragedy, a shock, or an aberration. It's a way of life. For 28-year-old Chicago native Tina*, the first shooting she witnessed at 9 years old didn't even feel like an emergency. She and her sister watched from their house as a car full of men pulled up, got out, and started shooting at a house across the way.

"They kicked the door in shooting at the man, the man's brother come out the window. They were all shooting. But that's my whole life," she says. "My whole life."

After the shooting, there were no TV cameras or public cries for justice. Kids on the street call Tina's neighborhood the "Holy City," a string of Vice Lords-controlled blocks so forsaken they could be confused for the scene of a permanent war. In fact, in this case, it is: By 2011, Chicago's 10-year murder rate exceeded the number of American soldiers killed in Afghanistan.

Though they go largely ignored in the media, neighborhoods like these in cities like New York, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Selma are ground zero for the bulk of gun violence in this country, and the gangs that form within them are responsible for 48 to 90 percent of America's violent crime. For girls like Tina, who are raised on these streets, joining a gang isn't a choice—it's a default.

"Growing up it's like, before it's even called a gang, it's just your friends. You're all just hanging out every day," she says.

Tina was expelled from high school her senior year for a fight, and began spending more time on the street. But unlike in the '80s or '90s, when her choice would have been to take a beating or to hook up with the right gang member to get into a gang, for Tina, her future was about finding her sisters.

In the modern girl gang, protecting yourself is about showing swag. It's about proving you're the baddest bitch they've ever seen. And a lot of it happens on social media.

"First there were three of us, then five of us, then eight of us. At school, people got scared of us, because we'd all cliqued up, and then in the neighborhood they were like, 'Oh you part of a gang.' That's how it is," she explains.

In the modern girl gang, defending your group and protecting yourself—from rival gangs and sexual abuse—is about showing swag. It's about proving you're the baddest bitch they've ever seen. And a lot of it happens on social media.

Two years ago, Gakirah Barnes, nicknamed Lil Snoop after the Wire character, went viral when she posted an Instagram of herself with her .357 Magnum. Before she was fatally shot in the chest by a hooded gunman at the age of 17, she'd been involved in 20 gangland murders, mostly for revenge.

According to Keith Woodley, program director at outreach program SLAM in Chicago, the girl-group clashes he's witnessed have started as disagreements on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. "There was a story here where a girl was arguing on Facebook and said, 'Why don't you meet me at this place and I'll shoot you,' and the girl actually brought a gun and shot her," Woodley recounts.

Though girl gangs aren't considered the primary perpetrators of gun offenses, it's easy to see how they could grow into the role. Gang violence in the United States is on the rise after decades of decline—James Howell, Ph.D., of the National Gang Center says there's been an 8 percent increase in the number of gangs over the past five years, and a 23 percent increase in gang-related homicides.

What's driving it, according to the center, is the dissolution of major gangs like the Bloods, Crips, and Latin Kings into smaller factions that fight each other. And this time, girls are standing their ground. According to the National Gang Intelligence Center, young women represent about 10 percent of all gang members, and in some places, they're "forming their own sets and committing violent crimes comparable to their male members."

Tina's story is one of thousands of similar stories playing out across the country.

"Historically, the view was that bad girls join gangs to hang out with bad boys," says Robert Lombardo, a gang expert at Loyola University in Chicago. "But now they join gangs for the same reasons boys do." Namely: friendship, safety, and a potential way out of poverty.

"My ex used to buy me nice shoes, fresh new shoes. I was popular and all that," Tina says of a guy she dated during her gang years, who supported her with the money he made selling drugs. "Some girls, the real pretty girls, real pretty from nice families who dress nice, they just want to come out for the boys. But then there's girls who know what's going on and like what's going on, like me. They like the game and the fame."

Tina says she was never involved in homicides, but she racked up a slew of misdemeanors as a gang member: obstruction of justice, contempt of court, domestic battery. When she had disputes at home with a boyfriend—which sometimes escalated—she knew her gang would back her up. "My child's father, we shot at each other. I shot at him, he shot at me," she says. "But I wasn't scared, because I knew once I go outside with my friends, they'll be like what's wrong, who did it."

And while male gang members used to refrain from shooting at women, or at men when women and children were around, that's no longer the case. "The girls is treated no different from the boys now," she says.

It's been three years since Tina realized how dangerous her life had become. Dealing drugs and hanging outside with a gun, she knew she was just waiting for violence to find her; she needed to get out or risk leaving her three children motherless. "I realized how real it was," she says. "Hindsight, I don't know who invented it, but wow, you see how stupid you were."

Tina made the transition quietly, without drastic incident—a dangerous process that many don't attempt. "A gang is something you can't get out of," Tina says. "I've been living the life since I was 12 years old. The only way out is to move out of state."

She could have run, or followed the informal "witness protection program" of changing her name, changing her life, changing her friends. But she didn't have that luxury. "My kids are still young," Tina explains. "I ain't ready to take them away from their dad." So instead, she stayed in plain sight: "I started working, going out of town. I got married."

She still lives in her former clique's neighborhood, and now her life is a balancing act between respecting their boundaries and avoiding danger by staying indoors and keeping her head down. "I don't stand outside carrying guns. I still gotta watch my back—they haven't forgot about the times I shot at them. But I'll be like, 'Hey, how ya doing.' I've learned how to move around."

But for thousands of young women like Tina, in Chicago's tough neighborhoods and cities around the country, the violence continues, unabated.

*Name has been changed

Chapter 5: The Lobby

How the NRA Is Rebranding—with Women

The steadfast group takes a progressive tack.

by Julia Sonenshein

In a slick, well-produced roundtable discussion hosted by Susan LaPierre, NRA Women's Leadership Forum co-chair and wife of NRA executive vice president Wayne LaPierre, members sit together on plush leather couches and declare women the new face of the NRA.

"It's no longer some grubby, dirty, unshaven guy in camo," observes executive committee member J.P. Puette in the View-type video, available on NRAWomen.TV. Sandy Froman, former NRA president, says, "Haven't you noticed that women seem to be so much more receptive and interested in the NRA than maybe five or 10 years ago?"

While the image many Americans have of the National Rifle Association is predominantly male, these women are right: That's all changing. In the past few years, the NRA's messaging has developed a distinctly female tone, actively courting women members across ages and gun literacy levels.

In 2013, the NRA launched NRAWomen.TV with the tagline "Armed and Fabulous." A year later, womenbegan to appear prominently in NRA advertising. And in 2015, the NRAblog began to include content specifically for women:hunting recipes, femaleguest bloggers, a personal essay entitled "Yes, I'm a Girl and I Shoot Guns."

"Haven't you noticed that women seem to be so much more receptive and interested in the NRA than maybe five or 10 years ago?"

For a group not often seen as progressive, it's a surprisingly forward-looking shift. Jeremy Greene, director of marketing and media relations at the NRA, tells MarieClaire.com that the organization believes women are the fastest-growing cohort of firearms owners in the United States. And the NRA is keen to welcome them. (External data doesn't reflect the same spike in women's gun ownership—according to the MarieClaire.com and Harvard Injury Control Research Center survey, 12 percent of American women own guns, which is consistent with previous ownership rates.)

New NRA members Shayna Lopez-Rivas, Rebekah Hargrove, and Gabriella Hoffman

Greene highlights the NRA's long-standing Women on Target program, an instructional shooting course developed in 2000 "in response to persistent calls from women who wanted to learn how to hunt and shoot, preferably in the company of other women." Annual participation in the program's shooting clinics has grown "between 12 and 20 percent per year since its inception, and over 70 percent since 2008," he says (the NRA does not release overall membership numbers by gender). It's been so popular that the NRA has even added a Female Instructor Development initiative "to help meet the demand for more women instructors across the country."

New NRA member Gabriella Hoffman, the 24-year-old founder of the blog Counter Cultured, is the daughter of immigrants who "lived under tyranny in Soviet-occupied Lithuania—and that's what compels me to support the Second Amendment and responsible firearms use." She believes that "guns, not government, are the great equalizer," and has found the NRA very welcoming since she joined in 2015.

Twenty-two-year-old Rebekah Hargrove, president of Florida Students for Concealed Carry, who also joined the NRA in 2015, echoes similar sentiments: "They're doing a wonderful job of reaching out to women. As a Hispanic woman, I feel that they adequately speak to me—even through age and cultural barriers."

A major talking point in the NRA's women-centric messaging is personal safety—and for women, that means self-defense. Greene points out that "women say the single most important reason they decide to purchase or own a firearm is protection, both personal and at home."

NRA member Shayna Lopez-Rivas—who joined in November—says she was raped twice while she was in college, once at knifepoint. "I was actually very anti-gun before that," she says, but she became a gun user when her friend took her to a shooting range to teach her how guns could be used to defend herself. She is now an activist for the group Campus Carry.

Hargrove also feels that being gun literate keeps her safe: "Being a trained woman who carries a gun gives me a much better chance at survival if my life is ever in danger, and the NRA defends that right."

"Women's issues are highly intertwined with equality and freedom. And that, to me, is what the NRA exemplifies."

Statistically, self-defense gun use in the U.S. is so rare that it's hard to get a realistic picture of it, says David Hemenway, Ph.D., director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center. In fact, in the MarieClaire.com and Harvard Injury Control Research Center survey, less than 1 percent of women used a gun in self-defense in the last five years.

And the NRA's inclusivity of women, both in branding and in membership, isn't necessarily new, points out Josh Sugarmann, executive director of the Violence Policy Center. He maintains that the association has been trying to reach women since the 1980s—but with different, and less empowering, tactics. Back then, the NRA focused on fear. The idea of rape was ever present, and "the pitch to women is simple: You're a woman. Someone is going to rape you. You'd better buy a handgun."

Recent advertisements from the NRA

Sugarmann attributes the NRA's renewed focus on women to a decline in firearm owners more broadly. A 2015 report from NORC at the University of Chicago, an independent research institution, found that gun ownership has been steadily decreasing since the 1970s, even though the relative number of female gun owners has risen. As the core group of gun owners—white men in upper income brackets—die off, women are more crucial to the NRA than ever.

It's a smart political move. Women represent a huge portion of the electorate: The Center for American Women and Politics says that since 1964, the number of female voters has exceeded male voters in every single presidential election—the 2012 election saw 9.8 million more female voters than male voters. With gun control already a factor in the upcoming presidential race, the NRA's increased female ranks could help further its cause.

Whether the NRA is retaining the women it recruits remains to be seen. But to new member Hargrove, the organization is critical to her sense of what she's entitled to as an American woman: "Women's issues are highly intertwined with equality and freedom. And that, to me, is what the NRA exemplifies."

Chapter 6: The Access

"What Happened When I Tried to Buy a Gun"

The process isn't as simple as we've been led to believe.

by Whitney Joiner

Technically speaking, I grew up in a house with guns. "Family guns," my mother called them: old shotguns passed down from grandparents and great-grandparents, locked in a cabinet in our basement in Louisville, Kentucky. But I'd never thought about owning one myself. I'd never even shot one until my late 20s, out on a West Texas ranch with my girlfriends, taking turns aiming at a lineup of old Tecate cans.

A record 3.3 million background checks were conducted this past December for Americans hoping to acquire firearms. It's a process President Obama wants to make more stringent (although that's proving to be harder than he'd hoped), and according to the MarieClaire.com and Harvard Injury Control Research Center survey, 62 percent of women agree with him. But amidst all the discussion and debate about access to guns—with Facebook and Instagram banning private gun sales on their platforms just two weeks ago—what does gun access really look like on the ground? When you're a woman trying to buy a gun for the first time, what happens?

On the Sunday before Christmas, I walk into a gun show in Evansville, Indiana, a two-hour drive from Louisville through flat farmland and winter-bare trees. It's one of the 44 gun shows held across the country that same weekend. In a former armory the size of a high school gym, roughly 60 dealers sit or stand behind tables, displaying handguns, rifles, boxes of ammunition, and hunting gear. I count 10 or so women, both buying and selling, and a few couples holding hands. Little boys chase each other in a corner. A concession stand sells Cokes for a dollar.

A guy in his mid-20s, grinning widely, stands behind one of the tables closest to the door. He's an unlicensed dealer, without much merchandise. "I'm interested in a handgun," I tell him, "but I'm not sure exactly what kind."

He tells me I should shoot a few different models first. He seems amused at how little I know and gives a short primer about 9MMs versus pistols. I nod as he goes into the vocabulary: magazines and rounds and clips, as if I know what he means. Women like the small 9MMs, he says. They can easily fit in a handbag and are easier to handle for smaller frames. I marvel at how light the gun is: It's barely larger than my hand. It's not pink and shiny; it doesn't scream, "This is for a woman!" But it might as well.

"How would I buy one?" I ask. "You need to have an Indiana license, and answer 'No' when I ask if you're a felon."

"That's it?" I ask. "That's it," he says. No background check needed. Since he's selling from a private collection, he operates in the infamous no-man's-land of the gun show loophole, which Obama's now trying to close. (It's the licensed dealers that are required to do a background check on any potential buyer.)

But then we hit a snag: He says he can't sell me one if I have an out-of-state driver's license, which is what, as an editor now based in New York, I have.

I'd been warned about this. Before coming down South, I'd contacted a few gun-buying experts, one of whom had cautioned that I might be stopped by my driver's license. In most states, you can only buy a gun if you can prove that you're a resident of that state. And yet in all the discourse about how easy it is to get guns—the popular narrative being that it's possible to just walk into a gun show or contact a private seller online and become the proud owner of a firearm—this important fact seems to have gone missing. It's actually not always easy.

I have the same problem with the next seller I visit. "What if I want to buy this?" I ask, holding up a small black Ruger, similar to the handgun I'd looked at earlier.

"Do you have an Indiana driver's license?" he asks. When I shake my head, he says, "Oh, yeah, no. You can definitely not buy a gun. You might be able to buy from a dealer here and have it shipped to a dealer back home…" He thinks for a minute. "You should talk to her," he says, motioning to a nearby table stacked high with ammunition boxes, partially blocking the view of the woman sitting behind it. "This lady is from out of state, and she's wondering if she can buy something," he explains to her as he deposits me in front of the table.

Since there are only a few women here, I immediately feel a kinship. "Okay, so I didn't tell you this," she says. "But there are unlicensed dealers here. Just ask if they require paperwork. If they don't, you can walk out with a gun."

I try one last time. At a table nearest to the exit, a man is selling an impressive selection of Glocks, slightly bigger than the tiny guns the first dealer had. A buyer sits across from him, filling out a background check and eating a piece of concession-stand German chocolate cake. The New York license is a real problem, the dealer tells me. He reminds me about Michael Bloomberg's gun show sting operation in 2009, when the then-mayor sent buyers undercover to shows in Nevada, Ohio, and Tennessee to prove how many guns were illegally making their way back to the city.

I now see why New Yorkers might not be the most welcome of gun show patrons.

After the gun show, I'm slightly more prepared to talk about what type of firearm I'm looking for. My brother and I walk into a pawn shop down the highway from our mother's house in the Louisville suburbs. I ask for a Glock, one of the most popular handguns for both women and men.

All the Glocks go first, the clerk at Cash Pawn America says. Each store's merchandise is listed daily on an app, so professional gun buyers are in and out all the time, snatching up the good stuff.

At first he seems taken aback at my wanting to buy one: This is for you? "Oh, is that surprising?" I ask. "Not at all," he responds, drawing out his words. He knows he's offended me.

No Glocks, he tells us, but he has something similar: a Springfield, for $420. I'll take it, I say. The background check comes out. I read some of it aloud to my brother as I fill it out: "'Are you under indictment for a felony?' No. 'Have you been convicted of a felony?' No. 'Are you a fugitive from justice?' No. 'Are you an unlawful user of marijuana, or have you been addicted to marijuana in the past?' No."

But, just like at the gun show, my New York ID stalls the process—they can't really sell to an out-of-state resident. "Aw, I should have asked you beforehand!" the frustrated clerk says. He was going to make a $40 commission on my sale, and now they'll still have to pay to process my background check. "I was excited for you, too."

Next we try our local Walmart, which sells long guns—meaning rifles and shotguns—but not handguns. The only warning sign asks that buyers have a valid driver's license, but there's nothing about needing a particular state of origin. Maybe this is my chance.

It takes awhile to get the clerk's attention. "Oh, do y'all need something?" she asks. I wonder if it's because she thinks we look out of place. She says she's been selling one or two guns a day thanks to the holidays, all for "protection" and as gifts for elderly parents. "People were going to work late just to get one," she says. "One guy was buying one and his work called him like five times to ask when he was coming in."

We pick out a Savage rifle. "It'll take about 30 minutes," she says. "I can't sell it." She pages a manager, and my brother and I wait—and wait. And wait. "It's interesting that you have to be 18 to purchase a shotgun," I say, pointing to one of the legal notices above the counter, "but 21 to purchase handgun ammunition."

"It makes no sense," she says.

When the manager finally arrives, it's the same story: "I can't sell this to you," he says. He points to a partially hidden sign that's not immediately visible: a map with Kentucky in red, and the seven states touching it—Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Tennessee, Missouri, Virginia, and West Virginia—in green. The rules for purchasing a gun change depending on where you are: which state, what kind of entity is distributing the firearm (gun show, corporation, LLC), and what kinds of guns are being sold (handguns versus long guns).

It's not arbitrary, but it feels that way.

Finally, we try stores that specialize in firearms. And since many of Louisville's options are closed for the holiday week, I'm not surprised that 111 Gun Shop is packed with customers.

"A lot of Christmas money," the guy behind the counter tells me.

"First gun?" he asks, when I request a Glock 19. "Great first gun."

At this point, I'm prepared when the sale stalls after I offer my license. "You have to be a resident of the state where you're buying," he says. "And your state is very unfriendly to guns. Are you a resident of Kentucky?"

"Not anymore," I say.

"You need to move back home."

"What if my parents bought it?" I ask, suggesting a straw deal.

"You'd go to jail and your parents would go to jail," he says. "Trust me. You don't want to get caught with a gun in your state. Not that we don't want your money. You need to go home and pack."

Back in New York, I walk into John Jovino's, the oldest gun retailer in the city (although there aren't many, and the two others only sell long guns). This small Little Italy shop sells handguns to police officers and other law enforcement officials; the owner has no patience for tourists.

Here, instead of being roadblocked for an ID issue, there's a gun license issue: We go back and forth about how I can get a license, how much it costs, and whether it's better to have the retailer do all the paperwork for a higher fee. After many rounds of questions, he seems exhausted.

"Okay?" the owner asks, as if to say, Are you done and Will you leave? "I'm busy now. I have a customer," he says, and vanishes to the other side of the store. While I'm waiting to get his attention again, a hipster couple and their friend walk in and look around.

"Oh, we're just looking," they tell him, before wandering out. I wonder how much the curiosity level from passersby has been piqued given the current climate, and if his obvious annoyance with me is from a sense that I'm not a true customer or about my gender.

Actually, I haven't experienced overt discrimination throughout this (admittedly fruitless) process. Instead, it came in minor forms: the surprise, the push for a lighter gun, the suggestion of something easier to handle that could fit in my purse. But experts in female gun ownership will tell you that women are especially diligent about their gun purchases—more likely to do more research, to ask friends and family, to take safety courses. It might be counterintuitive, but for some women, a heavier gun is a safer one.

But that's information to file away for later: For now, I leave the shop—without a Glock or a gun license.

Chapter 7: The Need

"I Wish I Had a Gun That Night"

Amanda Collins was raped after class on her college campus. Now she's haunted by what ifs.

by Amanda Collins, as told to Kaitlin Menza

I had just taken a midterm. It was 10 p.m. on October 22, 2007, a chilly night for Reno, where I was an undergrad at the University of Nevada. A few classmates and I walked to the parking garage together after the test—my car was parked on a different level from theirs, so I wished everyone a good week and broke off from the group.

I didn't see the man hunched down by the wheel of a truck. But I felt his hands grip my body when he grabbed me from behind and shoved me down on the cold asphalt. He pressed a pistol to my temple—I heard the click as he switched off the safety. He told me not to speak. And then he raped me.

I felt each vertebra in my back grind into the ground as this large man thrust himself on top of me. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see the university police's cruisers parked nearby, but their offices were already closed. No one was coming for me.

If you're going to be a target, don't be an easy one. That's the lesson my parents instilled in my sister and me from a young age. Growing up in Reno, we were taught to take responsibility for ourselves so we didn't have to rely on anyone else.

The desire for a gun was intrinsic for me. One of my earliest memories is of sitting on my dad's workbench in the garage while he cleaned his rifle. As soon as we could talk, my sister and I got the gun-safety speech from our parents: Always treat a gun like it's loaded; here are the different parts; a gun is not a toy. My dad took me to target practice for the first time when I was 6 years old. Eventually, I was on the rifle team in high school. Guns have always been a part of my life.

So as soon as I was old enough—for my 22nd birthday—I asked my father to pay for the class to get my concealed-carry permit. He did even better, and supplied me with a firearm and ammunition as soon as I obtained my permit. I carried my gun with me at all times.

Until I couldn't. My college, like many schools in the U.S., doesn't allow students to carry a firearm on campus. Even if you're licensed, even if you've been trained.

I didn't want to break the law, so I left mine at home.

As my body was being ripped apart that night in the parking lot, I wondered if these were the final moments of my life. I could see in his eyes that he might kill me. If I'm being honest, a part of me hoped I was on my way to meeting Jesus; living after this disgusting invasion seemed impossible.

The question I've faced ever since is: Would things have been different if I had had my weapon that night? I replay those eight minutes over and over and over again when I'm trying to sleep, imagining what I could have done, and I always reach the same conclusion: I could have stopped the attack if I'd had my gun.

Sometimes it fills me with rage. I did everything right. I stayed in well-lit areas, I never walked alone at night. I took martial arts classes. I learned to shoot and got my permit. I had a gun that I was—or should have been—allowed to carry with me. My rapist certainly did it.

Thirteen months after my attack, he was captured by the Reno Police Department. In the year since, he had kidnapped and raped a second woman, and then raped and murdered a third. He was tried and convicted.

Guns in schools is a sensitive, emotional subject for many. But the law meant nothing to my attacker. And when I tell my story, people often change their position. Even if they wouldn't carry a firearm themselves, they begin to understand why the government shouldn't prevent everyone from doing it, so long as they go through the proper channels. That's all I ask: for people to consider the other side.

I wish I'd had a gun the night my entire life changed for the worse, and I believe every college student—as long as they're of age and hold their permit—should be allowed to carry one if that's what makes them feel safe. For my part, I know I'll never stop fighting.

Chapter 8: The Sport

Inside the Life of a Teenage Competitive Shooter

Chapter 9: The Danger

For Women, Gun Violence Happens at Home

The most common threat doesn't come from a stranger. It comes from the person you sleep next to.

by Rachel Louise Snyder

When Brandi Moyler first tells me the story of her family, she talks about spring break at Myrtle Beach. She was 14 and had gone with a friend, and the night she returned home, she found her parents arguing. She fell asleep on the couch. Then she was walking through the dark house and her face was wet, so very, very wet. She kept wiping at it, trying to figure out what it was.

Here's the part of the story between the beach and the darkness: Her father fired five shots into the sleeping body of her mother with a .357 Magnum. Then Moyler, shocked awake by the noise, stumbled through the house to her mother's room, screaming, her father threatening her, Shut up or I'll shoot you too. But she can't shut up because her mother is lifeless in the bed, and her father is a beast in the dark, and so he does it. He shoots her. The bullet charges through her neck on the right, explodes her carotid artery, and exits just under her left eye through her cheekbone.

And so he does it. He shoots her. The bullet charges through her neck on the right, explodes her carotid artery, and exits just under her left eye through her cheekbone.

It's been nearly 18 years since that night, more than half her life ago. Her mother died instantly; her father hanged himself eight months later, awaiting trial for her mother's murder. And here's the thing she understands now: She'd always known it was going to happen—she was holding her breath waiting for it her entire life.

Moyler's story is not as unique as it should be. For many women, gun violence and domestic violence are the same thing; there are nearly 33,000 domestic violence firearm incidents in the United States every single year.

Of course, you don't have to be staring down the barrel of a gun for it to endanger you—guns are often used in domestic violence offenses as blunt-force instruments, as threats, as reminders of who holds the power. "It's not always an issue of being shot," says Teresa Garvey, a former prosecutor and attorney adviser for Aequitas, a prosecutors' resource for domestic violence law. "Guns are used to add to the environment of intimidation." Like many domestic violence victims, Moyler recalls seeing her father sit at the kitchen table cleaning his gun, a pointed reminder of his control over the family.

But as is also the case, guns often do the thing they were made to do: More than two-thirds of the domestic violence homicides in America every year are the result of guns. And it's not as though domestic violence homicides represent a small subset of the annual murders of women—they're the vast majority. A 2015 report from the Violence Policy Center reveals that 94 percent of women killed by men were murdered by someone they knew, and of those victims who knew their killers, 62 percent were either married to or intimate acquaintances of the men who took their lives. These statistics don't take unmarried exes into account, which would make the numbers even higher.

In Moyler's house, guns were everywhere. Her family lived on a small farm, and they slaughtered their own pigs every year. Guns hung on the walls as decoration. Handguns, shotguns, and hunting rifles were no more remarkable than the dishes in their cupboards. At the same time, the threat of guns always loomed: Every holiday, when relatives gathered at Moyler's home, her father, at some point late in the evening, would scream at everyone to get out or he'd go get his guns.

The single most common argument in favor of women's gun ownership is that it makes them safer. But "guns increase women's danger exponentially," says Kit Gruelle, a domestic violence advocate and principal adviser on the HBO documentary Private Violence. A New England Journal of Medicine study proves her point: Women who live in homes with guns are over three times more likely to be killed in the home. And when abusers have access to guns, a victim's risk of being murdered increases as much as eightfold.

Perhaps women have more awareness about this risk than we realize. In new research commissioned by MarieClaire.com and conducted by the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, nearly a third of American women live in a household with a gun, and yet more than half—in a survey of several thousand women across the country—want the next president to take strong action against guns.

Federal law does prohibit all felons and those convicted of domestic violence misdemeanors from purchasing or possessing guns. (Misdemeanors, it's important to point out, have a wide range of definitions, from a slap all the way to a near-fatal strangulation, depending on the state. Of South Carolina, Gruelle observes, "You get five years for hitting your dog and 30 days for hitting your wife.") But in a study by two of the country's leading experts on guns and domestic violence, April Zeoli and Daniel Webster, the prohibition made no difference in reducing the number of domestic violence murders. Lack of enforcement means there's very little follow-through. Where the laws do seem to have significant impact, however, is in areas with firearm restrictions for those with restraining orders—temporary or otherwise. Zeoli and Webster's study found that intimate partner homicides dropped by as much as 25 percent in cities where these laws were enforced (currently, only 30 states have such firearm restrictions in place).

Women who live in homes with guns are over three times more likely to be killed in the home.

The argument that asks women to arm themselves in self-defense is "asking them to behave as their abusers behave," notes Gruelle, who is also a domestic abuse survivor. "It's not a character flaw if a woman doesn't have a natural tendency to turn and fire on the father of her children."

And this is the crucial thing about domestic violence homicide, as Gruelle sees it: These killings are, in essence, ambushes—predatory murders like what happened with Moyler's mother, shot while she was asleep in bed. Or just last month, when Gladis Sicajan Albir was shot and killed by her estranged husband as she was getting into her car to go to work.

Brandi Moyler has spent her entire life grappling with what her father did to her family, but she sees the cycle that created him: He'd grown up in an abusive home, too. He had never seen any other way to be in the world.

What haunts her most, she says, is that ominous quiet after the shootings. "I remember so clearly that silence. I could hear everything inside my head."

Chapter 10: The Decision

To Own a Gun, or Not to Own a Gun

Grappling with a timely but troubling question.

by Roxane Gay

I have loved two gun enthusiasts in my life. When I was 20, I dated a man from Arizona who taught me the basics of shooting out on his pool deck, with a target and a gun loaded with wax bullets. There was something deeply satisfying about holding the heft of that pistol against the palm of my hand. I loved the instant gratification of pulling the trigger, a bullet zipping through the space between me and the target. I was powerful, holding that gun. In that moment, I understood the allure of gun ownership, of always having that power at one's disposal. It was a rush.

In my late 30s, I dated a hunter. He referred to his rifle as a "she," and during hunting season, he would spend innumerable hours in the woods, unclean and unshaven, staring through a scope, waiting for the perfect buck. He kept his guns clean and oiled, stored safely in a gun locker. He was a "responsible gun owner," a strong defender of the Second Amendment, but open to reasonable gun control legislation. We still argued about everything, all the time. Sociopolitical disagreement was the heart of our connection. But seeing how seriously he took his guns allowed me to consider some kind of middle ground.

"In that moment, I understood the allure of gun ownership, of always having that power at one's disposal. It was a rush."

As a woman, I always have to think about safety. It's there when I am walking to my car late at night, when I'm in a hotel room in an unknown city, as I lock up my apartment before bed, while strolling through the park. Though I try not to live my life fearfully, I am aware that danger lurks; that by virtue of my gender, there are predators in this world, and I am the prey.

As a woman who has survived a violent assault, I know there is no such thing as safety. The possibility that something terrible will happen is always present. It's not something that occupies much real estate in my active thoughts—instead, concern for my personal safety is a background process. An instinct, like breathing.

I watch the news along with everyone else when yet another mass shooting occurs, horrified by how cavalierly human lives can be taken by people, often men, with deranged agendas. A college campus, a movie theater, a post office, a Planned Parenthood clinic: I could be anywhere, doing any mundane activity, and find myself in a torrent of bullets.

As a black woman, my concerns about safety are multiplied by the nature of my skin. I am forced, increasingly, to worry about police officers who turn their guns, all too often, on unarmed black people. I spend more time than I should wondering, Is my life in danger from law enforcement? I do everything I can to not give a trigger-happy cop a reason to put a bullet in my black body, while I'm painfully aware that they do not need a reason.

Two years ago I moved to Indiana, an open-carry state. At first, it was disconcerting, seeing a random guy in cargo shorts and a worn T-shirt with a gun strapped to his hip, buying coffee at the gas station at 8 in the morning. When it happens, I tense up. I find myself holding my breath. I don't feel safe, but I imagine they do. Then the moment passes. My day goes on. It's almost scary how normal something like open carry can become.

Politicians love to talk about how if more people owned or carried guns, we'd see fewer casualties in mass shootings. We would be safer; we would all be heroes.

Yes, I want to feel like I can protect myself when I am confronted by danger. But I also know that in the heat of a dangerous moment, there is no predicting how I will respond. I might freeze up. I might run. I might start screaming. If I owned a gun and carried it, openly or concealed, I don't know what I would do. My hands might shake. I might not be able to dislodge the safety. I might not be able to shoot straight. I don't know if I would rise to heroics.

Or it comes down to this. Despite the ways in which I am forced to think about safety, despite statistics, despite the gun owners I have known and respected, despite politicians' hypotheticals, I recognize that to own a gun, to keep a gun in my home, to carry a gun on my person means I am taking on the responsibility of using that gun. I am taking on the responsibility of being willing to take another human life. And over and over—even as I lock my doors, even as I look over my shoulder—that is not a responsibility I am willing to bear.

Join the conversation on social media with the hashtag #WomenAndGuns.

Designed by Katja Cho.

Dedicated to women of power, purpose, and style, Marie Claire is committed to celebrating the richness and scope of women's lives. Reaching millions of women every month, Marie Claire is an internationally recognized destination for celebrity news, fashion trends, beauty recommendations, and renowned investigative packages.

-

I Need All of My Lip Products to Come With a Donut Applicator From Now On

I Need All of My Lip Products to Come With a Donut Applicator From Now OnI put four viral tinted serums to the test.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

Princess Margaret's "Ill-Mannered" Comments to Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mother Often Had "Courtiers Shaking Their Heads"

Princess Margaret's "Ill-Mannered" Comments to Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mother Often Had "Courtiers Shaking Their Heads"The late royal was known for her one-liners.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

How Prince Archie Has Been Learning About His Grandma Princess Diana's Charity Work

How Prince Archie Has Been Learning About His Grandma Princess Diana's Charity WorkPrince Harry shared that his 5-year-old son has become curious about one particular topic.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the Organization

EMILY's List President Laphonza Butler Has Big Plans for the OrganizationUnder Butler's leadership, the largest resource for women in politics aims to expand Black political power and become more accessible for candidates across the nation.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State Legislators

Want to Fight for Abortion Rights in Texas? Raise Your Voice to State LegislatorsEmily Cain, executive director of EMILY's List and and former Minority Leader in Maine, says that to stop the assault on reproductive rights, we need to start demanding more from our state legislatures.

By Emily Cain Published

-

Your Abortion Questions, Answered

Your Abortion Questions, AnsweredHere, MC debunks common abortion myths you may be increasingly hearing since Texas' near-total abortion ban went into effect.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do Next

The Future of Afghan Women and Girls Depends on What We Do NextBetween the U.S. occupation and the Taliban, supporting resettlement for Afghan women and vulnerable individuals is long overdue.

By Rona Akbari Published

-

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need Aid

How to Help Afghanistan Refugees and Those Who Need AidHow To With the situation rapidly evolving, organizations are desperate for help.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They Deserve

It’s Time to Give Domestic Workers the Protections They DeserveThe National Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, reintroduced today, would establish a new set of standards for the people who work in our homes and take a vital step towards racial and gender equity.

By Ai-jen Poo Published

-

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde Amendment

The Biden Administration Announced It Will Remove the Hyde AmendmentThe pledge was just one of many gender equity commitments made by the administration, including the creation of the first U.S. National Action Plan on Gender-Based Violence.

By Megan DiTrolio Published