My Journey to Finding Self-Worth in My Self-Harm Scars

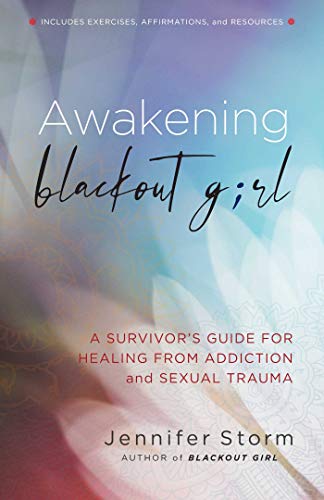

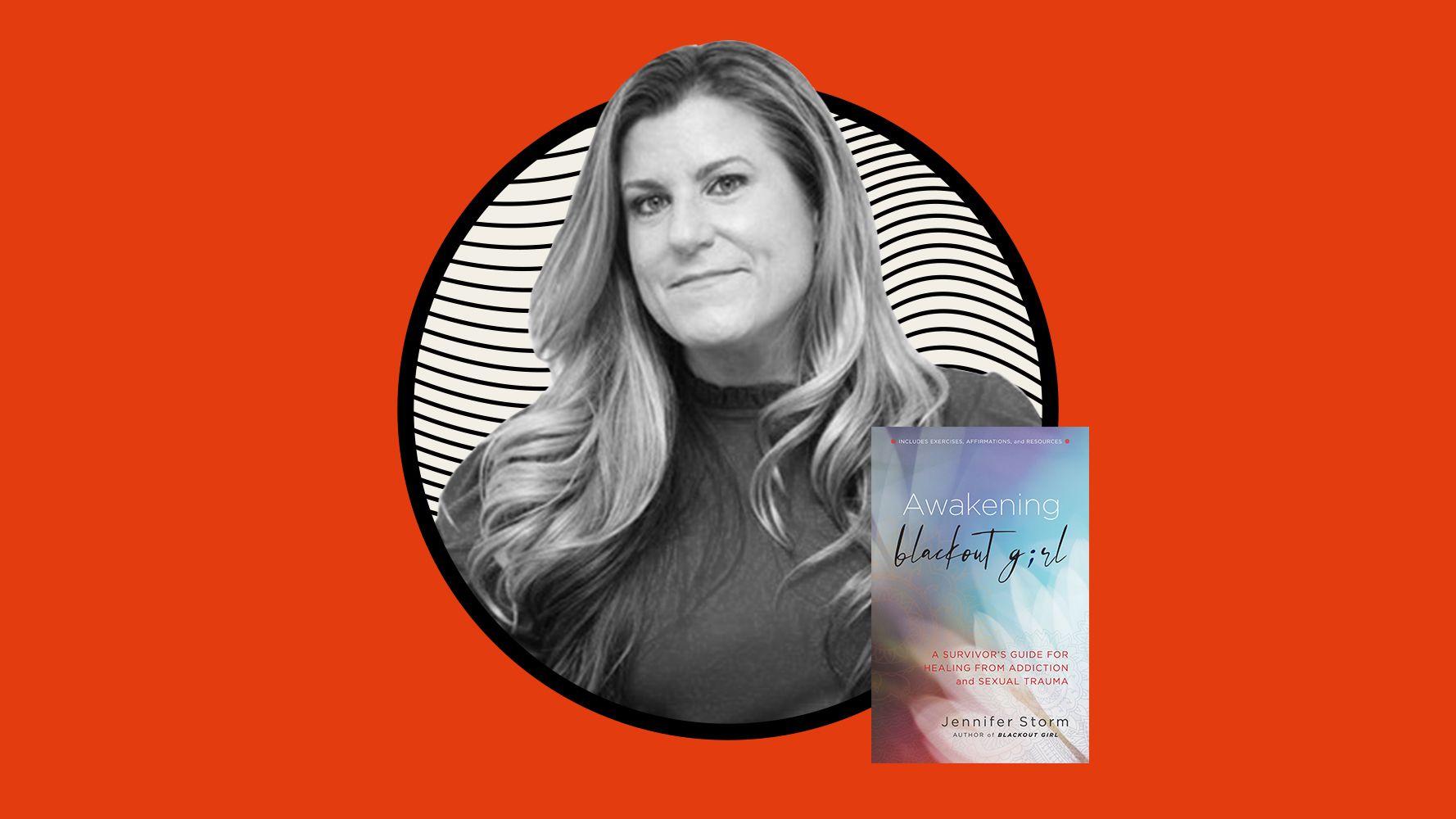

In honor of National Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, author Jennifer Storm shares an excerpt from her upcoming book, Awakening Blackout Girl.

CONTENT WARNING: The below story contains descriptions of suicide and self-harm. This content may be triggering for some readers.

In her honest and practical guide, Awakening Blackout Girl (out October 6), rape survivor and award-winning victim advocate Jennifer Storm shares the information, tools, and resources she has gained from more than 20 years of personal and professional experience to help fellow survivors recover from co-occurring sexual trauma and substance abuse. In this excerpt from her new book, Storm recalls the turning point that led her away from suicide and the work she put in to embrace her scars after years of self-harm.

My self-harm started shortly after I was raped when I was twelve years old. I was emotionally twisted and had no support or emotional outlet. My parents didn’t know how to deal with my trauma—my rape only brought all of their own childhood trauma to the surface. None of us had the smallest idea about how to cope with such intense emotions in a healthy way. One night, it became too much for me to contain within my small body, and I began to have extreme anxiety. I couldn’t handle the pain inside, so I attempted to quiet it. I grabbed a bottle of peach schnapps from my parents’ readily available liquor cabinet and rummaged through the kitchen cabinets to find a bottle of my mom’s Valium and my grandmother’s blood pressure bills. I did shot after shot while popping pills into my mouth. I called my mother to tell her what I was doing, my speech slurred. I hung up the phone and attempted to walk over to the sink to grab some water, but my legs were not working. They crumbled beneath me, and I slid onto the floor between our island and sink. The next thing I remember was EMTs coming into the house and carrying me to an ambulance. The lights eliminated my already-blurred vision, and I couldn’t see anything. I felt a tube being jammed down my throat, and a nasty taste filled my mouth until I leaned over and puked up black charcoal. Everything went black again.

This suicide attempt landed me in the ICU. I almost died from the medications but managed to survive. When I woke up, my parents told me that I would have to spend some time in the hospital’s psychiatric ward because it was deemed that I was a threat to myself. That’s where I spent my thirteenth birthday and the following summer. To say that this place was not trauma informed is the understatement of the century. It was like being dropped in the middle of a horror film. I was on a floor of the hospital with one long hallway with rooms on either side. My roommate was another girl who was about six years older than I was. She had long black hair and laid in her bed very quietly. I didn’t sleep a wink that first night because all I could hear were the screams of an older woman coming from across the hall. Apparently, she had been resisting treatment all day, and they had put her in four-point restraints. She just wailed all night long.

If you’ve ever seen the movie Girl, Interrupted, that’s exactly the type of place I was in, except there weren’t only women on my floor. And it wasn’t just for teens, either. There were people of all ages and genders. They put everyone together with zero regard for how that would impact us. And impact me, it did. I learned a lot during my summer-long stay. The older patients taught me how to lie to the doctors to get them to leave me alone. I learned how to tongue my meds so I didn’t really have to swallow them. I learned the value of various medications—what other patients would give you in exchange. Psychotropics were very valuable. Unfortunately for me, I was only on a low dose of antidepressants, which no one really wanted.

One day, I found my roommate sitting in the shower using a piece of metal she removed from the eraser of a pencil to make cuts on her stomach. She looked relaxed and peaceful. As my eyes wandered from her face down to the blood swirling into the drain, I screamed. She quickly jumped up, shushed me, and begged me not to say anything. I just starred in horror, and some fascination, at the scene unfolding in front of me. I asked her what she was doing. She replied, “Nothing, I’m fine, just leave me alone and please don’t tell anyone.” I spent a lot of time that day just sitting on the floor dumbfounded, thinking about what I saw.

A few months later, after being released, I sat in my own tiny bathroom lightly dragging a razor blade across my arms and remembering how peaceful my roommate looked slumped down in that shower. That look of serenity on her face provided all the courage I needed to plunge the razor deeper into my own flesh. That’s where I learned about self-harm, or “cutting,” as many call it today. It didn’t have a formal name back then. Cutting became a part of my dysfunctional survival routine. It gave me a temporary emotional release when I was in pain and didn’t have immediate access to a drink or a drug.

The scars no longer scared me. They no longer represented my self-hatred. Instead, they represented a part of my journey to healing, a path from my old life to my new freedom.

It was many years later, shortly after the death of my mother, that I experienced an emotional pain so overwhelming that I used a combination of alcohol and a razor to try to end my life again. That night, I created the scars that still linger on my wrists today. Luckily for me, that night also became my turning point. I woke up in the hospital with a realization that I didn’t want to die anymore. My life was worth living, and I needed to get sober and heal my trauma in order to save myself.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

When I first got clean and sober, I was incredibly embarrassed and filled with shame over the very visible scars on my wrists. For a long time, looking at these scars reminded me of the sickness I held within for so long. They made it clear that I had attempted to take my own life, and I felt that anyone who saw them would judge me as crazy. The only way to hide them was to wear long sleeves, which I did a lot. I would curl the material of the sleeve up over my hand and grasp it to hide the scars. This was before those cool sweatshirts with the thumb hook that easily hide your wrists. Those were made for runners to keep their hands warm, but they sure would have come in handy for me back in the day. Once summer hit and the weather began to get hot, I had to start accepting the fact that I couldn’t hide my scars all the time. I used vitamin E and a list of other products on the market that claimed to lessen the appearance of scars. Despite all my attempts, it soon became obvious that only time would slowly flatten the angry raised lines, and completely eliminating them would be impossible. I realized that I had to learn to live with them.

A part of learning to love myself was learning to love my scars. Each day, I made an effort to look down at them and gently trace them with my fingers. Often, I would even kiss them or hug my own arm. These simple, kind acts allowed me to physically love a part of myself that I had previous deemed non-viewable to the world. They allowed me to heal myself. By allowing myself to love my scars, I took the emotional and psychological pain away—I took my power back. The scars no longer scared me. They no longer represented my self-hatred. Instead, they represented a part of my journey to healing, a path from my old life to my new freedom.

If you’re thinking about suicide, are worried about a friend or loved one, or would like emotional support, the Lifeline network is available 24/7 across the United States at 1-800-273-8255.

Adapted from Awakening Blackout Girl by Jennifer Storm © 2008, 2020 by Hazelden Foundation.

RELATED STORIES