This story was reported with the Fuller Project, a journalism nonprofit reporting on global issues impacting women.

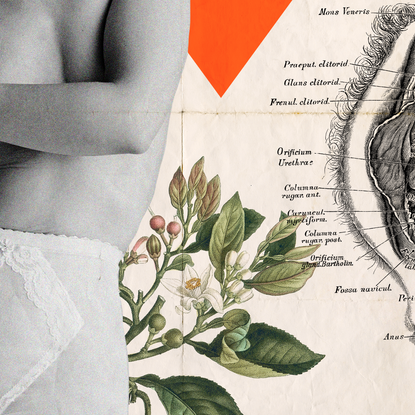

No medical procedure exists that can prove if a woman—or a man, for that matter—is a virgin. Yet, almost 500 years after the hymen was first “discovered,” myths about it remain widespread globally. We set out to dispel them.

Myth: The hymen is a seal across a woman’s vagina.

Reality: Every woman's hymen is different.

The hymen is a membranous tissue found near the entrance of the vagina, but it does not usually completely cover it like a seal. Most women have hymen tissue that surrounds the entrance of the vagina, forming roughly a doughnut or crescent shape. But hymens, like many body parts, vary widely in shape, size, and thickness.

“There is such a huge variation of what’s normal,” says Ellen Johnson, an ER nurse trained in sexual assault cases, who works to educate patients and juries about the hymen. Generally, Johnson uses a comparison to a scrunchie with ruffled edges to explain the tissue: “If you pull on the scrunchy, it expands and the ruffles smooth out,” she says. Still, “the hymen can have many different appearances.”

In rare cases, a woman might have an imperforate hymen, which blocks the vaginal canal; a microperforate hymen, in which there is a very small opening; a septate hymen, in which there are two small openings; or a cribriform hymen, in which there are many small openings. These rare conditions make it difficult to menstruate, use tampons, or have sex, and they may require minor surgery. But, for most women, the hymen won’t impact daily life at all.

Myth: The hymen exists to show whether or not a woman is a virgin.

Reality: The hymen's purpose is unknown.

Scientists aren’t exactly sure what biological role the hymen plays, but one theory is that the hymen helped protect baby girls from bacteria. Its presence or absence does not indicate whether a person has had intercourse. Virginity is not a medical term.

Myth: The hymen breaks the first time a woman has sex.

Reality: The hymen does not break.

The tissue might rip, stretch, or wear away, but it does not break. Just before girls hit puberty and then during, estrogen increases the elasticity of the hymen, meaning it can stretch, even after sex. As women age and participate in activities including sex and exercise, and experience childbirth, the hymen usually thins and wears away, though not always and not entirely.

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Some women experience bleeding or minor discomfort as a result of tissue tearing the first time they have sex—this could also be due to anxiety or lack of necessary lubrication and stimulation—but many do not. Despite this, many women are expected to bleed the first time they have sex, which has traditionally been during the wedding night. Often, whether or not a woman bleeds, or bleeds enough according to what’s expected, is directly linked to her value.

“I didn’t bleed [on my wedding night], so I have no value as a woman,” says Medina, a 19-year-old Afghan woman. Because she did not bleed, her husband left her, ruining her reputation (in her conservative culture, pre-marital virginity is demanded of women) and endangering her life.

Even in the United States, girls and women are seeking out expensive cosmetic surgery in order to “repair” or reconstruct their hymens so that they have a better chance of bleeding the first time they have sex or on their wedding night; plastic surgeons acknowledge they cannot guarantee this will happen.

Myth: A physician can determine if a woman is a virgin by checking her hymen.

Reality: No medical procedure exists that can accurately determine if a person is a virgin.

Although the hymen was long ago deemed a marker of virginity, modern medicine shows that it proves next to nothing. Some women aren't born with hymens at all. Other women have hymens that remain thick even after having sex as adults.

Yet some American medical professionals report performing virginity tests, in which two fingers or a speculum is inserted into the vagina in search of the hymen or to measure the elasticity of the vaginal walls, neither of which can demonstrate whether or not someone has had intercourse.

The bottom line is that virginity testing—even when carried out by a physician—is a sham.

Myth: Virginity testing is illegal in the United States.

Reality: The procedure remains legal in the United States.

Despite the World Health Organization calling on governments worldwide to ban virginity testing, Marie Claire and the Fuller Project have found that virginity testing is occurring here. The practice remains wholly unregulated. It is often forced on girls without their consent by parents or guardians, or on young women before they get married.

There are no federal or state laws banning virginity testing nor are there clear medical guidelines or standards of care from the country’s top medical associations, like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists or the American Medical Association. Hospitals and medical centers often have their own internal policies or none at all. The myth that an “intact” hymen—which is not an accurate medical description—is evidence of virginity is even dangerously present in courtrooms.

Marie Claire and the Fuller Project are committed to reporting on this issue. If you have been forced or coerced into undergoing a hymen exam, or submitted to such an exam willingly, and would like to share your story anonymously or otherwise, reach out to reporter Sophia Jones at sophia@fullerproject.org.

Sophia Jones is a senior editor and journalist with the Fuller Project, a journalism nonprofit reporting on global issues impacting women. To learn more about their work visit fullerproject.org.

-

Olivia Rodrigo Is Bringing Visible Bra Straps Back

Olivia Rodrigo Is Bringing Visible Bra Straps BackThe pop-punk princess wore custom Victoria's Secret at Coachella.

By Julia Gray Published

-

Meghan Markle’s New Netflix Cookery Show Begins Filming Today—But Not Where You’d Expect It to Be Shot

Meghan Markle’s New Netflix Cookery Show Begins Filming Today—But Not Where You’d Expect It to Be ShotThe Sussexes are having a busy week this week, shooting both of their his-and-her Netflix shows and rolling out the first product offering for Meghan’s new lifestyle brand American Riviera Orchard.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

How I'm Redefining My Wellness Journey in 2024

How I'm Redefining My Wellness Journey in 2024Sponsor Content Created With The Honey Pot

By Aniyah Morinia Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My Body

How Being a Plus-Size Nude Model Made Me Finally Love My BodyI'm plus size, but after I decided to pose nude for photos, I suddenly felt more body positive.

By Kelly Burch Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” Condition

3 Women On What It’s Like Living With An “Invisible” ConditionDespite having no outward signs, they can be brutal on the body and the mind. Here’s how each woman deals with having illnesses others often don’t understand.

By Emily Shiffer Published

-

The High Price of Living With Chronic Pain

The High Price of Living With Chronic PainThree women open up about how their conditions impact their bodies—and their wallets.

By Alice Oglethorpe Published