The Trip of a Lifetime

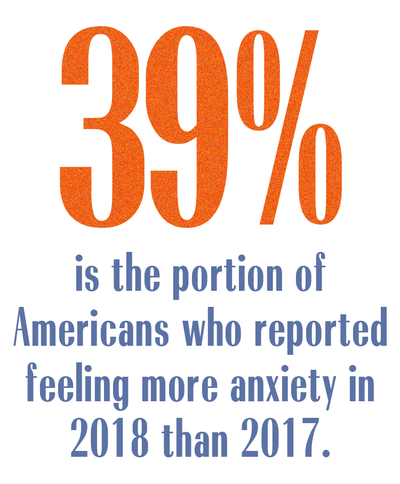

Women across the country are self-treating their depression and anxiety with hallucinogenic mushrooms. Is it working?

When Audra was a teen, she began to buckle under uncontrollable feelings of doubt, self-consciousness, and panic that made going to school or even hanging out with friends torturous. “I could barely make it through the day without feeling like I was dying,” she remembers now. She learned she had anxiety and ADHD at 15, but the diagnosis just gave a name to her issues—it didn’t solve anything. She took antianxiety medication but felt it just pushed all her panic deep inside without actually making her feel better.

By the time Audra reached her 20s, she endured feelings of anxiety that sent her thoughts spiraling. Meanwhile, her self-doubt held her back professionally: When she had an opportunity to write an essay or publish her photographs, she turned it down. After all, she figured, who was she to have a voice in the world?

“I told myself I wasn’t worthy, that I could not be unbroken,” Audra says. “I thought I would always need to be on medication in order to feel like everyone else, and that made me feel like such an other.”

Then, a year ago, the advertising creative director in NYC, learned about and began experimenting with “microdosing”—taking roughly a tenth of a dose of psychedelic mushrooms several times a week. Within a few hours of her first dose, she felt more comfortable using her own voice, less self-critical, and more open to connecting with others. What she didn’t experience: hallucinations, synesthesia, or communion with the spirit world.

The dried and ground magic mushrooms she takes in a gelatin capsule aren’t a magic bullet; she’s not “cured” of her decades-long battle with depression and anxiety. Yet her lows aren’t as devastating. “When I do have bad days, I’m able to separate myself from a feeling of worthlessness and stop telling myself the story that I shouldn’t try to connect, shouldn’t be curious, shouldn’t create,” Audra says. “Microdosing helps me recognize that I’m still whole.”

Plant Medicine: A Growing Trend

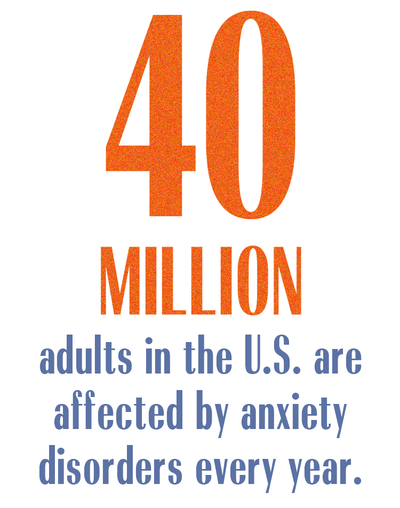

Audra is one of thousands of women across the U.S. and in Canada and Europe who self-medicate with tiny amounts of mushrooms that contain the psychedelic compound psilocybin—which the United States Drug Enforcement Administration classifies as a potentially harmful schedule 1 drug with high potential for abuse. But the issue of legality doesn't stop them. They share advice on how to use psychedelics to manage symptoms of anxiety and depression through networks like Reddit and private Facebook groups, and at local psychedelic society meetings.

Most microdosers use a regimen laid out by James Fadiman, Ph.D., in the 2011 book The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide: One-tenth of the amount needed to trip on psilocybin-containing mushrooms (or other drugs, such as LSD, which contain other psychedelic compounds), one day on, then two days off for about a month. Most people take between 0.1 and 0.4 grams of psilocybin-containing mushrooms while microdosing, which doesn’t produce the technicolor trips of Grateful Dead concerts and hippie communes. Of course, with no one prescribing this self-treatment, individuals tweak the regimen based on their own experience.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The number of people subscribing to the r/microdosing Reddit forum has roughly tripled in less than two years, to more than 50,000—a number that ticks upwards daily. The forum itself, as well as news stories, mainstream books like Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind, and podcasts like Tim Ferriss’s episode on the trend, have stoked interest in what many proclaim to be a no-side-effect alternative to Big Pharma.

“It’s a growing phenomenon,” says Thomas Anderson, research director at the Center for Psychedelic Studies at the University of Toronto. Anderson and his research partner Rotem Petranker surveyed more than 900 people, over half of them microdosers, and the pair is in the process of applying for approval in Canada to conduct a double-blind study on the effects of microdosing while controlling for things like the placebo effect. Still, as Anderson admits, “We don’t yet know if this works at all.”

What Happens During Tiny Trips

Less ambiguous about the effectiveness of self-prescribed psychedelics is Mercedes, a 36-year-old yoga instructor from Canada, who swears by the power of magic mushrooms. “Microdosing is like defragging your computer, but for your brain or soul,” she says.

Mercedes has struggled with mental health issues all her life, with her first major depressive episode coming in her late teens. Later, she was diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. For years, Mercedes tried antidepressants and “substances, alcohol, drugs—anything to distract myself from feeling how I was feeling,” she remembers. Then two years ago, her therapist mentioned microdosing, and it spurred her to seek out more information at a spirit medicine conference.

Microdosing, combined with other self-care practices such as yoga and mindfulness, has been “transformative,” Mercedes says. She points to a recent trip she took to London that triggered feelings of overstimulation and exhaustion: “How I would have handled that in the past was to drink or distract myself. But I didn’t do that. Instead of dwelling on my issues for weeks and succumbing to obsessive thoughts, I processed my emotions and let them go in a few hours.”

Anderson and Petranker’s research, published in the journal Psychopharmacology, found that people who currently microdose or who have tried the regimen in the past scored better than a control group on several well-established scales that measure how vulnerable they are to depression. They also fell lower than a control group on measures of negative emotionality (being neurotic) and higher on creativity and wisdom—a term that includes forgiving past slip-ups and considering multiple points of view when making a decision.

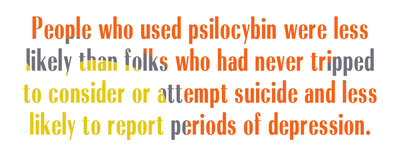

Another, more extensive survey echoes these findings. After combining data on nearly 200,000 Americans, researchers found that people who used psilocybin (but not other psychedelics) were less likely than folks who had never tripped to consider or attempt suicide and less likely to report periods of depression in the month before the survey. A Dutch study also suggested psilocybin may lessen anxiety.

Brain scans might reveal what’s behind these tantalizing results: Studies have found that psilocybin binds to serotonin receptors, which reduces blood flow to a part of the brain that’s overactive in people who are depressed. When this area is on hyperdrive, it can be hard to bust out of mental ruts (i.e. the “this will never get better” mentality). When it mellows out, people become more optimistic and mentally nimble.

This effect is more widely witnessed—and accepted by the scientific community—in large doses of psychedelics such as psilocybin. Doctors and therapists have begun to embrace therapy-assisted trips to help people with treatment-resistant depression as well as cancer patients and those staring down death. Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind pulls together results from studies that show that people with depression, in hospice, and undergoing cancer treatment tend to be less depressed for months and even years after taking psychedelics.

‘Shroom Skeptics

Not all researchers are convinced that microdosing is the life-changing superdrug proponents promise.

“If you take antacid for indigestion, you wouldn’t break a TUMS tablet into four pieces and get the same amount of relief,” says David Nichols, Ph.D. “There’s no reason to believe the effects you see at a therapeutic high dose would be the same at a low dose.”

Nichols, who co-founded the hallucinogenic-focused nonprofit Heffter Research Institute to study the therapeutic basis for psychedelic drugs and who is considered to be one of the leading experts on the pharmacology of mind-altering substances, thinks women like Mercedes and Audra are feeling a placebo effect. That is, they read accounts online or hear from a friend that psilocybin makes you more creative and less depressed, they expect to feel better, and poof—they feel better, too.

Safety is another question. Most people in Anderson and Petranker’s survey report mild side-effects. Some have trouble with temperature regulation—at room temperature they can feel too hot or too cold, or even both at the same time—or feel nauseated.

More concerning to critics like Nichols is dosage. Unlike synthetic psychedelics such as LSD, the amount of psilocybin in magic mushrooms varies with the species, the batch, even the cap versus the stem. It’s hard to measure, then, exactly how much psilocybin you’re getting in a dried mushroom. (Many microdosers rely on other people to produce chocolates or gummies with a consistent dose of psilocybin, or they dry and grind mushrooms before weighing and packaging it in capsules.) What’s more, research has established that between 30 and 50 percent of medications for long-term conditions aren’t taken as prescribed. It follows then that many people—including those with a mental health diagnosis, such as anxiety or depression—may have trouble sticking to a medication regimen, such as the one-day-on, two-days-off rhythm suggested by Fadiman.

When Jean, who works in university administration in the Washington, D.C. area, tried microdosing two years ago, she was hoping to take advantage of the reported creativity boost for her work and personal art, as well as benefit from the mood boost, since she was going to therapy already. After lurking on microdosing forums and talking to people who had tried it themselves, she started eating a mushroom cap about the size of her fingernail every morning before work.

Though she didn’t see sounds as colors or have a major trip, she did become “flighty:” She’d forget her wallet at home, lock her keys in the car, or send confusing emails to her colleagues. “I wondered if I was having mini-strokes,” says Jean, who prefers we use her middle name because using psychedelic mushrooms could compromise her job. “Then I realized, duh! I’m microdosing.”

It’s true Jean was taking mushrooms much more frequently than Fadiman’s regimen recommends, and her self-prescribed treatment illustrates another potential danger of microdosing: Remember how psilocybin binds to a serotonin receptor, which is how researchers think the compound relieves depression? When that receptor is stimulated, it causes the growth of connective tissue in the lungs and heart valves.

“If you take LSD or psilocybin once a month, you’re not continually stimulating that receptor, so your chances of suffering from valvular heart disease are pretty low,” Nichols explains. “But the regimen for microdosing is every three to four days, and some people are taking it every day.”

Despite these dangers, psilocybin doesn’t seem to trigger the same reward networks many other drugs do, which means it doesn’t seem to be addictive. Or deadly—you’d have to eat more than 37 pounds of magic mushrooms to ingest a lethal dose of the drug.

Still, Nichols is unequivocal. “I don’t see the benefit of microdosing.”

A Long, Strange Trip

The benefits of taking a full, hallucination-causing dose—also called a “therapeutic dose” or even a “heroic dose”—is better documented. Researchers in the U.S. are currently studying the effects of large doses of psilocybin on treatment-resistant depression, end-of-life mental health, and substance abuse, with proposed studies on anorexia, PTSD, and Alzheimer’s on deck.

Many people are trying “heroic doses,” too, either independently or while supervised by therapists or other “guides.” Sue, a mom in Portland, Oregon, had tried dozens of antidepressants and mood stabilizers over nearly three decades without much relief and sometimes with side effects like fevers and rashes. The 48-year-old had never done any drug, let alone 'shrooms, or even smoked a cigarette, but when she heard about the seismic shift in outlook experienced by a friend’s son who tripped, she became “interested—but clueless,” she says.

Another friend connected her with someone who makes magic mushroom candies. She arranged for a babysitter to watch her kids for the day, asked her partner to stay with her, and downed a full dose of the hallucinogen.

“The trip removed an element of hopelessness that had been there for a long time,” she remembers. “It was like a Zamboni just rode over my brain: Every neural pathway you’ve laid down, all the ruts, all the habits, they smooth out. You get this ability to identify what caused you to form those ruts, and where you want to lay down new pathways.”

Sue describes being able to look at her old patterns with a gentleness she’d never experienced: She realized she’d been using her identity as a quiet introvert as an excuse to tamp down her opinions. “I had this big insight that it’s okay to be quiet, but not to silence my voice.”

Even more impactful than the insights Sue gained was the experience of the trip itself. She found herself laughing until tears rolled down her cheeks at the simplest of things, like the way the leaves moved in the wind outside her window, she says. “I realized it’s in there, joy is in there. I’m not a pit of darkness and pain.”

Centered Communities

Ironically, the very thing that helps with the self-confinement of depression and anxiety can itself be isolating.

Take, for instance, Julie. She struggled with anxiety and depression during her 20s, which kept her “subdued, at home, isolated,” she says. Microdosing mushrooms alleviated those feelings and tendencies to retreat into a shell of herself. But she found psychedelics were too much of a taboo to discuss openly.

“This is something that’s not mainstream. It’s hard to find pockets of open-mindedness in Michigan,” says Julie, 45, a therapist.

That’s why two years ago, she founded a psychedelic society in Michigan. The group hosts monthly meetings with speakers on topics like “Commodifying the Sacred.” Talking with others who are passionate about mind-altering substances has made her more comfortable talking with people who are curious—or even those who see magic mushrooms as akin to heroin or cocaine. “We need to have discussions, share experiences, find out more, educate the public, and encourage harm reduction,” Julie says.

It turns out there is a neural basis behind this desire to reach out: Psilocybin disrupts the usual connections between the parts of the brain that are active when people think about themselves. Quieting this “ego center”—which is also overactive in people who have depression—might account for the feeling of connectedness that comes up again and again among microdosers.

Mercedes, the yoga instructor in Canada, says kinship is one reason microdosing has helped her deal with depression, anxiety, and PTSD in a healthy way. “Psilocybin helps me realize my connection to everything around me in an amplified kind of way, to remind me I’m not alone in my feelings,” Mercedes says. “I’m not alone at all. None of us are.”

Tripping in the Future

Even if you take out the fundamental question of whether microdosing works or not, the reality remains: It’s illegal.

The women interviewed for this article were careful to talk around how they found psilocybin-containing mushrooms, wanting to keep their sources safe from law enforcement. And many asked that we leave out identifiable details—yes, to stay on the better side of the law, but also to avoid repercussions like losing a job or shade from the PTA.

Just as the majority of the country has begun to embrace medical and recreational marijuana, though, the tide may be shifting for psilocybin-containing mushrooms. In Oregon, a pair of therapists are working on gathering enough signatures to put a measure on the 2020 ballot that would legalize therapeutic doses of psilocybin, to be taken in the presence of trained providers and followed by “integration therapy” to process the trip.

And in Denver, activists gathered enough signatures to put the question of decriminalizing magic mushrooms to voters. In May, the measure was approved and the city became the first location in the U.S. where possessing or using psychedelic mushrooms is the “lowest law enforcement priority.”

Nichols is less enthusiastic than the triumphant advocates in Denver. “People say the next thing is mushrooms, that they’re sort of benign,” he says. “The use of psilocybin in a therapeutic context—with a trained psychologist and physicians on call and drugs that can reverse its effects—is different than buying a bag of mushrooms on the street and saying, ‘I’m going to treat my depression.’”

Even if small amounts of psilocybin or other psychedelics were found effective to treat mental health disorders, prescribing it would add a whole new level of complexity. “They’d never let you take a month’s worth of microdoses home: If you took 10 of them, you’d have a recreational dose,” Nichols points out.

Still, the same can be said of other legal substances—alcohol, for example, or even cold medicine. Drink half a bottle of cough syrup and you’ll be “robotripping”—hallucinating on a completely legal substance that costs $10 at Walmart.

Amy Jackman, co-owner of a cannabis consulting business in Alaska, isn’t waiting around for a scientific seal of approval. She takes a microdose of mushrooms a few times a month when “I start feeling myself getting down or notice patterns I’ve been in all my life,” like struggling to get out of bed or realizing she’s still in her pajamas at dinnertime, she says. The 47-year-old has microdosed on and off for the last five years—less in the summer and more in the winter, when the sun doesn’t peek over the trees at her house until well after 10 a.m.

Now, within a few hours of taking a half-gram of powdered mushrooms in a gel capsule, Jackman looks forward to chores and tackling work, and she doesn’t hear the critical voice inside her head comparing her simple life with friends’ cheerful Facebook updates. “It’s like the heavens have opened up to me, and I’m at my full potential,” she says.

Psychedelic mushrooms have become one part of her self-designed treatment to battle depression, which also includes seeing a naturopath, saunas, smoking cannabis, and sound therapy with Tibetan singing bowls. She has found a combination of care that keeps her productive, creative, and connected to her family—and she’s not changing that because of ambiguous science.

“I know my body better than anyone else on this planet, and I know mushrooms help bring the joy back in my life,” Jackman says. “There is no doctor, lawmaker, or politician who can tell me what’s best for me. I’m not hiding.”

For more stories like this, including celebrity news, beauty and fashion advice, savvy political commentary, and fascinating features, sign up for the Marie Claire newsletter.

-

Tyla's Coachella Outfit Pairs Dolce & Gabbana With Pandora

Tyla's Coachella Outfit Pairs Dolce & Gabbana With PandoraThe singer wore a gold version of the crystal bra made famous by Aaliyah.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

How Kate Middleton Is Influencing George's Fashion Choices

How Kate Middleton Is Influencing George's Fashion ChoicesThe future king's smart blazer is straight out of Princess Kate's style playbook.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

King Charles "Couldn't" Meet Prince Harry During U.K. Visit

King Charles "Couldn't" Meet Prince Harry During U.K. Visit"It could actually bring down a court case."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

I Work Out 5 Days a Week—These Are the Brands I Wear on Repeat

I Work Out 5 Days a Week—These Are the Brands I Wear on RepeatSponsor Content Created With Nordstrom

By Emma Walsh Published

-

The Wellness Issue

The Wellness IssueLooking at women's health through a new lens.

By Marie Claire Editors Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

Raven Saunders Is Getting Another Shot at Life—and the Gold

Raven Saunders Is Getting Another Shot at Life—and the GoldThe Olympic shot putter almost didn't live to see the Tokyo Games. Now, she's gearing up to compete while advocating for mental health in the sports world and beyond.

By Rachel Epstein Published