It Took 7 Miscarriages, 10 IVF Cycles, 9 Years, and Nearly $200,000 to Solve My Fertility Issues

It involved a trip to Moscow and disregarding everything I'd been told by expensive U.S. and U.K. fertility doctors.

After six miscarriages, six fresh in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles, two frozen IVF cycles, and one healthy not yet two-year-old daughter, I was told by my New York–based fertility specialist and embryologist to give up on having another genetic child. I had just turned 40. Though I had spent nearly $200,000 on fertility treatments in the U.S. and the U.K.—a staggering sum—my previous two IVF cycles had produced precisely zero useable embryos. The seasoned professionals at my clinic in New York gently told me that it was time to face facts: I likely had no good eggs left. Experts I had seen over the previous eight years echoed their opinion.

Throughout the course of my fertility journey, I had been “blessed” with the ability to produce lots of eggs. The IVF cycle that brought us our daughter had been no different than its predecessors: twenty-eight eggs retrieved, seventeen fertilized, and thirteen mature embryos on the third day of their existence—science-speak for a reassuringly ample supply. But genetic testing revealed a startling result: only three of our embryos were chromosomally normal. Although I was panicked, the doctor calmly reminded us that he was only planning to transfer two embryos, and he was confident that he had found a “super embryo.” Nearly nine months later, we welcomed our beautiful, perfect, healthy, and so-longed-for daughter into our world.

Although 28 eggs had been retrieved, only three of our embryos were chromosomally normal.

When we decided to try for another baby less than a year later, self-assured in light of our previous success, we thought the second time around would be easier than the first. But the fertility rollercoaster is full of surprises. My cycle was shockingly different. I produced eight eggs, which resulted in five embryos, none of which were normal. Eight months later, we tried again, this time with a drug protocol boosted higher than ever before. I had eight eggs and eight embryos. Again, none were normal. And that is when we were gently, but firmly, told I no longer had viable eggs. We were counseled to move on.

During my many years of trying to conceive, I had been a stalwart participant in the whisper network—the women who talk to each other over coffee, lunch, and wine, who post in internet chat rooms and on fertility blog sites, all searching for the elusive information that might help them have a baby. I had turned to the network when I wasn’t ovulating, when I had Clomid headaches, and when I wanted to learn what side effects to expect from my first IVF cycle. I read about clinics in Spain and Cyprus, surrogates from India and Thailand. The network of whispering women often provided more useful information than my doctors. It had, subtly, become such a part of my life that when I finally tried to turn it off, the network was still there. When my husband and I moved to Dubai weeks after being told to "move on," friends, friends of friends, and cousins of acquaintances reached out with their fertility questions; despite my lack of good eggs, I was seen as a success story.

Then a woman name Michelle from New Zealand called and asked why I hadn’t considered treatment in Russia or Ukraine. She told me that those countries, along with Israel, had among the highest IVF success rates in the world at some of the lowest costs. The whisper network confirmed this: Pursuing high quality, low cost treatment, women were traveling to Russia and getting pregnant. Having endured over a dozen miscarriages, Michelle, at 43, decided to try once more at the AltraVita Clinic in Moscow. She became pregnant with twins and urged me to go see her doctor. I was torn. We had a wonderful daughter and had already put much of our pain and anguish behind us. Our hopes had been raised then crushed so many times, and the financial toll had been enormous.

But two months later, I found myself in Moscow, shifting in my chair opposite Dr. Oxana at AltraVita, her inscrutable face skimming her notes for what seemed like a very long time. I asked if she thought it made sense for me to try IVF again, as I didn’t seem to have any good eggs left. “You wouldn’t know if you had any good eggs,” she replied. “The high level of drugs you took would have ruined them. You may have several.”

You wouldn’t know if you had any good eggs. The high level of drugs you took would have ruined them.

Dr. Oxana's plan began with a homeopathic detox regime to help rid my body of the hormones I had pumped into myself during my multiple IVF treatments in New York and London; she insisted that the damaging levels of hormones in my body were compromising my egg quality. Then, once I was detoxed, I would begin IVF, on a short protocol, at a very low level of drugs. When I started to express my concern that there wouldn’t be any eggs to retrieve at those dosages, she became frustrated. Either I accepted the clinic’s philosophy or I didn’t and went elsewhere, she said.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

In the West, Dr. Oxana explained, most doctors believe that the chromosomal health of a woman’s eggs is essentially determined at birth and degrades with age. The job of the fertility specialist is to coax out the highest number of eggs to find the “healthy” ones. In Russia, many fertility specialists believe that the environment in the body, and in the outside world, greatly affects the health of the eggs and thus the embryos produced; that diet, toxins, chemicals, hormones—especially in high doses—had potentially harmed the eggs I was so desperately trying to harvest. Rather than stimulating the production of as many eggs as possible to find the proverbial needle in the haystack, Dr. Oxana sought to gently stimulate the production of only a handful of eggs, hoping to find one or two good ones.

As I struggled to process this staggering thought, Dr. Oxana went further. She and her colleagues believe, radically, that egg quality can be improved. Egg quality is not static, she said, and it can go up as well as down. I had been given 600 units of Puregon, the drug that stimulates egg production, during my last IVF cycle. “At that level, all your eggs would be damaged,” Dr. Oxana said. Instead, she used 150 to 250 units. “We will probably have only four eggs, but half should be normal. That is all you need.”

Could this really be true? Could the basic premise of five torturous, expensive, and sad years’ worth of IVF—the very cornerstone of Western medical reproductive orthodoxy—be wrong? Could I still have good eggs? I remember sitting in stunned silence, contemplating the time, money, and trauma I had subjected myself to, potentially unnecessarily, for half a decade.

Fewer eggs equals more babies, at drastically lower costs.

While most US fertility doctors have traditionally advocated the position that chromosomal errors in eggs accumulate gradually over 30 to 40 years and are beyond our control, research teams in the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, India, Japan, and Russia have found that conventional ovarian stimulation protocols may have a negative effect on egg quality, causing women to produce fewer normal eggs and embryos than those with a mild stimulation protocol (or no stimulation at all). These studies show that many chromosomal abnormalities actually occur in the weeks and months before an egg is ovulated, opening the door to a window of opportunity in which improving the quality of eggs is, to some extent, within our control—through, for example, increasing certain nutrients and supplements known to support normal egg growth and development and eliminating exposure to known toxins, such as BPA and phthalates. Yet it is precisely during this window that women pursuing IVF undergo ovarian stimulation protocols that may damage their eggs. These scientists concluded that lower doses of stimulation drugs could significantly improve embryo quality and fertilization rates. One study, from Spain’s Valencia School of Medicine, showed that retrievals of more than ten eggs produced lower-quality eggs and lower fertility rates than retrievals of ten or fewer eggs, while another found significant increases in rates of fertilization and chromosomally normal blastocysts in reduced-dose IVF cycles. Fewer eggs equals more babies, at drastically lower costs.

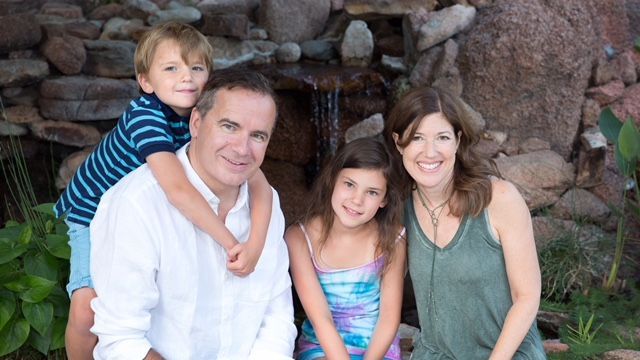

As it turned out, Dr. Oxana was right about everything. I followed her every instruction for a few months and, after two rounds of IVF, produced eight healthy eggs, which developed into four embryos—all for a total cost of approximately $4,000. I got pregnant, twice. One ended in another miscarriage, but one became our son, William. As Dr. Oxana told me, her skeptical American patient, at our first meeting: “It only takes one good egg. What do you want so many for?”

Elizabeth Katkin is the author of Conceivability: What I Learned Exploring the Frontiers of Fertility, on sale June 19, 2018.

-

Selena Gomez Is the Cropped Blazer Trend's Final Boss

Selena Gomez Is the Cropped Blazer Trend's Final BossThis style simply works on her.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

The Most Striking Beauty Moments in Met Gala History

The Most Striking Beauty Moments in Met Gala HistoryElaborate and extraordinary.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Princess Madeleine Can't Use Royal Title to Promote Skincare Line

Princess Madeleine Can't Use Royal Title to Promote Skincare Line"I will use my name Madeleine Bernadotte in my work with MinLen."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar Published

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain Published

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung Published

-

The High Price of Living With Chronic Pain

The High Price of Living With Chronic PainThree women open up about how their conditions impact their bodies—and their wallets.

By Alice Oglethorpe Published

-

I Used to Imagine Murdering the Men I Dated

I Used to Imagine Murdering the Men I DatedFalling in love helped me finally figure out why.

By Jessica Amento Published

-

60 Workout Apps for Women Who Want Results (Without a Gym Membership)

60 Workout Apps for Women Who Want Results (Without a Gym Membership)Buying Guide Easy fitness plans you can follow without fear of judgment.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published