My Eating Disorder Made Me Feel Like a Feminist Fraud

I was aware of the patriarchal systems that governed the world, and I was a confident young woman. So why wasn’t I acting like one?

When I started restricting calories, I felt like a god—in possession of a secret skill that allowed me to exert control over my life in a measurable way. It all happened accidentally.

The summer before ninth grade, I found out that my dad was cheating on my mom and that my parents were separating. Suddenly, I felt like my life was spinning out of control. I didn’t intend to be anorexic—I was simply too anxious and angry to eat. So I didn’t, and weight fell off my lanky, adolescent body.

My appetite reappeared as I got used to the state of my family’s trauma; I resisted it. I didn’t want to give up how powerful I felt forcing the pounds off. Resisting my own hunger quickly felt sacred to me. Starvation was a ritual that reminded me I could be strong. And it was my secret, enabling me to create a boundary between myself and the rest of the world—especially my family.

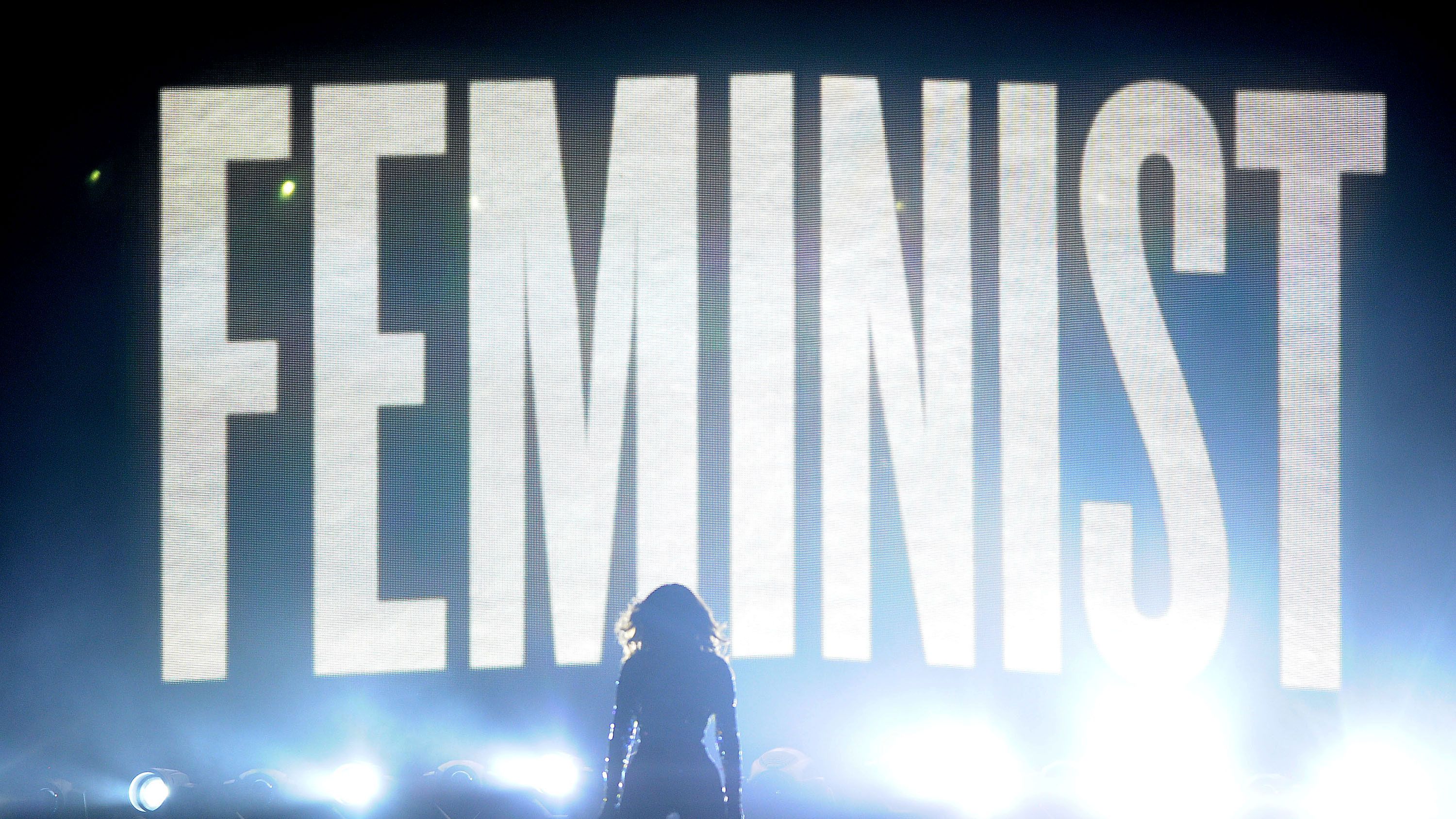

Other girls count calories. But not you. You’re a feminist.

Like many people who suffer from disordered eating, secrecy was my most notable symptom.

I was committed to being seen unquestionably as “chill” and “easygoing.” That kind of person would never be anorexic. Other girls count calories, I’d tell myself. But not you. You’re too strong, too smart, too normal. You’re a feminist.

Ironically, I became interested in feminism the same year my obsession with losing weight began—age 14. When I first experienced the ecstasy of weight loss, I felt caught in a paradox. Emotionally, I was intoxicated by my discipline. Intellectually, I was horrified by my capacity for self-neglect. I was aware of the oppressive, patriarchal systems that governed the world, and I was a confident young woman. So why wasn’t I acting like one?

For most of high school, I navigated gradations of anorexia, though I couldn’t admit it to myself then. I was committed to the performance of normalcy, and experimented with a variety of dramatic approaches. Sometimes, I dieted excessively, giving others the impression that I was a staunch health nut. On other occasions, I simply wouldn’t touch food until sundown, spending lunchtime in the library getting ahead on homework. That way, I could go to the gym after school and work off the calories that I’d consume during dinner—a normal meal with my parents, who’d gotten back together after a year apart. There were sporadic times I’d let myself eat chips, cookies, chocolate, and other junk with friends to show them I was “normal.” The hatred I felt for myself after those episodes became a source of motivation, and I’d deprive myself of food entirely for two days. Through all these phases of disordered eating, I was crippled by fear. Of food, of weight gain, of pleasure, of embodiment. Maintaining the illusion of control was my biggest priority, even if that meant losing my period, my social life, and my personality in the process.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

One day, midway through junior year, an idea dawned on me: I could start enjoying food again—without swallowing it. “Chewing and spitting” was the answer I’d been looking for all along. It gave me the “benefits” of anorexia without anyone knowing that I was doggedly responding to the demands of patriarchy. I could be unnaturally skinny, but no one saw me working against nature for it. It was flawed logic, but that was my logic nonetheless.

RELATED STORIES

Chewing and spitting (a.k.a. “CHSP” or “C+S” among clinicians) isn’t a freakish, gross habit that only a few of us know about. It’s a widespread (but still poorly understood) phenomenon in the clinical landscape of eating disorder diagnosis and treatment. Chewing and spitting is regarded as a behavior among clinicians—comparable to restricting calories or laxative use. Several studies, including one from Johns Hopkins University, frame chewing and spitting as a symptom of anorexia, bulimia, and/or OSFED (Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disturbances), and suggest that it may be an indicator of disease severity.

The first day I chewed and spat, I bought a bag of pretzels at Whole Foods and chewed the entire thing in my bathroom, intermittently spitting out sludgy blobs of taupe mush when my mouth got too full. Tasting carbs for the first time in years was euphoria. Chewing and spitting was the real-life equivalent of “having your cake and eating it too.”

When I went out to dinner with friends, I could order undressed salad without looking uptight, because I was also “eating normally,” which meant chewing and spitting pieces of bread, side orders of French fries, small “tastes” other people’s pasta. All it took was a keen awareness of the other person’s eye contact (so I could time my spits), and a graceful technique for wiping my mouth with a napkin.

Of course, if chewing and spitting were actually a perfect loophole, I’d probably still be doing it to this day. What started as a sporadic indulgence quickly spiraled into an obsessive-compulsive routine that cost me significant amounts of money, time, and energy. About three times a week after school, I’d spend roughly $30 at my neighborhood grocery store on sugary cereals, crackers, and cookies only to flush it all down the toilet in its pulverized form an hour later. The whole process was exhausting and demoralizing.

Eventually C+S actually caused me to gain weight (skyrocketing my anxiety in the process). After all, digestion starts in the mouth. Our food begins breaking down into sugars our bodies can use as energy when it comes into contact with saliva. Tasting entire boxes of cookies, cereal, and milk duds was pleasurable, sure, but they also gave me debilitating tooth aches and serious cavities, one of which required root canal. When I asked Gail Grace, leading psychotherapist at the Eating Disorder Resource Center in New York City, about potential health risks of chewing and spitting, she gave me a laundry list, including dental complications. “You may be releasing insulin, but not digesting the food,” she added, which some people believe could contribute to pre-diabetes.

With the increased frequency of chewing and spitting came increased secrecy, which put strain on my relationships. I regularly had to explain to friends and family why I was acting cagey, where I’d disappeared to during dinner. “People are distressed by all different parts of the behavior,” said Evelyn Attia, M.D., director of the Center for Eating Disorders at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. “By how secretive they've become. By how much money they're spending on food that they're getting rid of. By how uncomfortable their mouth or teeth or salivary glands might feel.” Needless to say, there is nothing glamorous about beige globs of pretzel mush.

How could I criticize patriarchy at the same time as I responded dutifully to it?

Going to college disrupted my chewing and spitting “routine.” I was forced to live with roommates and without my parent’s kitchen, which had given me 24/7 access to a menu of food options I curated daily. The obstacles made sustaining the addiction a lot less appealing. Plus, my new life in the academic pressure cooker encouraged another addiction—to the amphetamine-based stimulant Adderall—that took the place of chewing and spitting. Weight loss was no longer the motivating force of my self-torture. (Eventually, after hitting a very, very low point, I overcame that addiction.)

Though I said goodbye to acutely disordered eating habits in college, I was and still am crippled by body image issues and an ongoing preoccupation with food. Now that I’ve come out of the eating disorder closet—to my therapist, my friends, my family members, and of course, to myself—I have begun to think more critically about the relationship between my history of disordered eating and my feminism. About how my political interest in rejecting straightforward starvation ultimately led me to an equally pernicious habit: conjuring self-confidence in public, while playing mean tricks on my body behind closed doors.

Looking back, I see chewing and spitting as my painfully optimistic (and failed) attempt to show the world a more liberated sense of myself than I actually felt. The shame of anorexia that enveloped me about wasn’t so much about being ill as it was about being anti-feminist. How could I be committed to gender equality and dismantling destructive societal norms at the same time as I enacted the very behaviors keeping me locked in a cycle of self-destruction? How could I criticize patriarchy—and the pressure it put on women to shrink ourselves into invisibility—at the same time as I responded dutifully to it? Answerless at the time, I did what any perfectionist would do in the presence of a question mark: I pretended to know the answer, and the best answer I had was chewing and spitting.

Paradoxes inevitably emerge between the personal and the political. Of course you can be a feminist and struggle with body image issues. Being susceptible to eating disorders doesn’t make you a perpetuator of patriarchy. Patriarchy will oppress us for our appearances and appetites no matter what it is they look like. To be a hungry woman with an appetite, according to patriarchy, is to be voracious and pleasure-seeking, devoid of discipline and principles. Cultural critic Susan Bordo identified these qualities when describing “the archetypal female” in her pivotal 1993 book on the politics of anorexia, Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. To starve oneself as a woman, then, is to not fall prey to desire. It’s an attempt to express strength, discipline, principles—to be as heroic as we can be within the confines of a system that aims to oppress us. Patriarchy tells us that we’re damned if we do, and we’re damned if we don’t.

We now hear resonances of this tension in cultural conversations about female sexual liberation, particularly in the #MeToo moment. When a woman is sexually harassed or abused, patriarchal culture instructs to blame her—to ask what “slutty” outfit she was wearing or what other behavior she might’ve been doing to “ask for it.” At the same time, patriarchy conditions us to regard women who are assertive about their sexual boundaries as “frigid” or “uptight.”

Susceptibility to whatever manifestation of patriarchal oppression—be it silence in the face of sexual harassment or starvation in the face of unachievable body norms—is the hand we’ve been dealt as women, and feeling guilty about our coping mechanisms isn’t going to help any of us. What we can do is acknowledge the contradictions, talk about them, question them. And when self-judgment knocks at our doors, as it inevitably does, we can acknowledge it too without letting it come inside. We can lay our cards on the table. We can be both.

MORE ON EATING DISORDER AWARENESS WEEK

Charlotte Lieberman is a Brooklyn-based writer whose work often concerns feminism, meditation, and mental health. You can read her articles in Cosmopolitan, The Harvard Business Review, BOMB,Teen Vogue, and Guernica, among other publications, and her poetry in The Boston Review, The Colorado Review, and Nat.Brut. Visit her at www.CharlotteLieberman.com.

-

Prince George Looks Just Like a Young Prince William During Fun Night Out with His Dad and Billionaire Godfather

Prince George Looks Just Like a Young Prince William During Fun Night Out with His Dad and Billionaire GodfatherThe 11-year-old joined his father and the Duke of Westminster for an exciting football match in Birmingham.

By Kristin Contino

-

All the Fashion Girlies Are Trading High Heels for These $110 Ugg Slippers

All the Fashion Girlies Are Trading High Heels for These $110 Ugg SlippersThey're the key to red carpet recovery.

By Kelsey Stiegman

-

10 Vacation Destinations Inspired by Beloved TV Shows

10 Vacation Destinations Inspired by Beloved TV ShowsWhether you're ready to experience life like the lords and ladies of 'Downton Abbey' or you're craving an 'Emily in Paris'-style adventure.

By Amy Mackelden

-

There's a Huge Gap in Women's Healthcare Research—Perelel Wants to Change That

There's a Huge Gap in Women's Healthcare Research—Perelel Wants to Change ThatThe vitamin company has pledged $10 million to help close the research gap, and they joined us at Power Play to talk about it.

By Nayiri Mampourian

-

BetterMe Will Make Your New Year’s Resolutions Last the Other 12 Months

BetterMe Will Make Your New Year’s Resolutions Last the Other 12 MonthsSponsored BetterMe: Health Coaching uses a psychology-based program to approach your health goals from all angles, so they stay within reach.

By Sponsored

-

Everlywell's At-Home Test Kits Are 40% Off

Everlywell's At-Home Test Kits Are 40% OffThe testing company is offering big savings on some of their most popular kits.

By The Editors

-

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"

Senator Klobuchar: "Early Detection Saves Lives. It Saved Mine"Senator and breast cancer survivor Amy Klobuchar is encouraging women not to put off preventative care any longer.

By Senator Amy Klobuchar

-

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?

I'm an Egg Donor. Why Was It So Difficult for Me to Tell People That?Much like abortion, surrogacy, and IVF, becoming an egg donor was a reproductive choice that felt unfit for society’s standards of womanhood.

By Lauryn Chamberlain

-

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in Check

The 20 Best Probiotics to Keep Your Gut in CheckGut health = wealth.

By Julia Marzovilla

-

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo Olympics

Simone Biles Is Out of the Team Final at the Tokyo OlympicsShe withdrew from the event due to a medical issue, according to USA Gymnastics.

By Rachel Epstein

-

The Truth About Thigh Gaps

The Truth About Thigh GapsWe're going to need you to stop right there.

By Kenny Thapoung