My Sister's Keeper

What happens when you lose an identical twin? Christa Parravani was 28 when her sister, Cara, died. Odds put her chances of meeting the same fate at 50 percent, and she started down a self-destructive path — until writing their story set her free.

I used to be an identical twin. I was Cara Parravani's twin. I forgot who I was after my sister died. I tried to remind myself with a trinity mantra, which I whispered to the woman who stared back at me in my morning mirror: I'm twinless. I'm a photographer. I'm Christa. We were 28 when Cara overdosed. We had the dark hair we were born with; we had angular faces and we fancied red lipstick; we had knobby knees, slightly crooked eyeteeth, and fingernails bitten down until they bled. We had a touch of scoliosis — grade school nurses pulled us into their offices for yearly back checks. Cara had a steppage gait that caused her right foot to drag a little behind her left, an injury she sustained during a car accident in college. My stride is steady, but my posture is horrible; Cara stood straight as a pin — her shoulders were proud and strong and she held them back. I slouched. She said I went round like a little worried pill bug; I'd roll up into a ball tight as a fist. We both flinched at the smallest sounds: slamming doors, quick gestures, and laughter if the pitch was too high. We had looks and fear in common.

During the closest years of our lives, Cara liked to fasten bobby pins into my hair and admire the updos she invented. We administered weekly sisterly beautification, little animals that we were. We applied honey face masks, avocado hair glazes, and salt scrubs. We performed on each other the tedious process of individual split end removal with a pair of haircutting shears. She called me her "raven sister with the sexy beehive." I called her "my messy, unmatching flower goddess." Of course, there were other names, the cruel and loving ones we give our siblings. Cara took her nicknames for me with her when she died: Pumpkinseed, Digger, Shave, and Newt.

I gazed at myself in the mirror and there she was. Her rusty brown eyes, frightened and curious as a doe's. In the mirror I'd smile at myself and see her grinning back. She was a beauty. And her square waist, narrow hips, and round breasts were now mine. I'd imagine all of my sister's regality and blemishes as part of my reflection: I saw Cara's weak chin, her cherry lips pricked into a bow, lipstick smudged at the corners of her mouth. I'd hold out my arms and turn them, exposing my bare forearms. I'd see each one tattooed with a flower from my wrist to my elbow. The stems of the flowers started at my pulse and grew up to the crook of my arm, blossomed. Cara had gotten these tattoos after many tough years, images that decorated and repelled. She had wanted to make sure she was rough enough around the edges that she seemed impervious to danger, but the part of her that needed to be dainty and female selected flowers to mar her body. She designed a garden to conceal the evidence of her heroin addiction. Her right forearm she marked with an iris. Her left arm she'd drawn up with a tulip. Tulips had been our grandmother Josephine's favorite flower, and the tattoo was meant to pay tribute.

My reflection was her and it wasn't her. I was myself but I was my sister. I was hallucinating Cara — this isn't a metaphor. I learned through reading articles on twin loss that this delusion — that one is looking upon their dead twin when really they are looking at themselves — is a common experience among identical twinless twins. It is impossible for surviving twins to differentiate their living body from their twin's; they become a breathing memorial for their lost half. Cara's reflection became a warning. I would become her on the other side of our looking glass if I wasn't careful. It wasn't only her likeness I craved. For me, her self-destruction was contagious. I mimicked it to try to bring her back. To be nearer to her, I tore apart my life just as she'd shredded her own.

I am the sole historian left to record our lives. It's difficult to know if my memories are true without her. We mixed our memories up. Our lives were a jumble. I can remember being where I never was, in places I never saw: my sister's marital chamber on her wedding night, the filthy hotel rooms of her drug buys, sitting at her writing desk as she tapped away at her keyboard. It wasn't uncommon for us to remember something that had happened to our twin. It can seem that I was the one who kissed Chad Taylor in the parking lot of our junior high school, his whale of a tongue bobbing back and forth in my mouth, his hands heavy as bricks on my hips. But it was Cara who kissed him. She claimed what was mine, just as I took what was hers. We shared everything until there was nothing of our single selves left. It was my task in grieving her to unravel the tight, prickly braid of memory rope we'd woven — to unwind and unwind and unwind until I was able to take my strand and lay it out beside the length that was hers. Cara's dying meant there was a strong chance I would soon join her. I read somewhere that 50 percent of twins follow their identical twin into death within two years. That statistic did not discriminate among cancer, suicide, or accident. Twins go by illness or the intolerable pain of loneliness. Flip a coin: Those were my chances of survival.

We were called the girls. Mom called us her ladies. Cara called me Her. One twin goes and the other must follow. I got ready to die. I starved. I lied, and I swallowed pills. I wet my marital bed. I cut my arms with a knife. I divorced. I refused sleep out of fear of dreaming of Cara. I allowed any man who wanted me to f--k my body of bones so I wouldn't have to be by myself. I lived alone in a house I filled with my sister's furniture. I crashed cars, and I quit my job. I checked myself into mental hospitals. I scared our mother. I turned my-self into Cara. I wanted to chase my sister into the afterlife. I saved myself at the brink of our two worlds. I cheated my own death. What one twin gets, the other must have. I declined my piece of our whole. I became a woman who owns half a story: I lived.

I don't know if I believe in the intuition of twins. The knowing, feeling, or knowledge of the whereabouts and pains of a double have always seemed impossible to me, even having one of my own. But when I found out about Cara, I was driving in Manhattan. And before the ringing phone in my lap was answered, I knew what I'd discover on the other line.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

I DISPERSED CARA'S ASHES in Hawaii, Thailand, Germany, and Hollywood. My sister has no grave marker, no memorial plaque, no stone with her name carved above a date. It was my choice that she have no resting place. Our family plot is in Schenectady, New York. Acres and acres of rolling hills that once abutted the forest are now directly beside a suburban shopping mall. To visit a relative there means to be in full view of Macy's and Sears and shoppers rolling their filled carts to waiting SUVs. I refused to abandon Cara in a dismal scrubby plot, in full view of mall employees and bargain hunters. There was simply no place to leave her, so I took her everywhere. I divided up her ashes and kept them in multiple bottles, urns, boxes, and satchels. I carried her for three years in my pocketbook. I have one container of ashes saved in a storage unit at the funeral home. I took her to California on assignment photographing a heavy metal band from the '80s. I brought her next to an artists' retreat in New Hampshire. I tossed some of her ashes into a ravine from the open window of a writing studio. When I traveled to the White Mountains with Cara's friend Danielle, we set her loose in a cold, black trout stream behind Danielle's in-laws' house, down a hill, past stalks of blue wildflowers and a ditch of tiny stones. I mixed her ashes into eyeshadow and dusted my lids. I dipped a wet finger into a baggie of ash and tasted her bones. I dropped an urn of Cara, spilling her, and vacuumed her up. I stared at her ashes for hours and marveled at the way they sparkled and at how light and free she had become. Lastly, I brought her ashes to Venice, as she had asked me to do, after a trip we took there once.

A YEAR LATER, I was admitted to the graduate writing program at Rutgers Newark and granted a fellowship — just like Cara had been at UMass Amherst. It is very difficult to explain the thing that happened to me through writing. It did what time and therapy and lovers never could. Because writing was the only way to be with Cara, to move again in tandem, writing won hands down over my grief. I knew that to write I must have a clear mind. I would need enough sleep and nourishment and sobriety to adequately tackle our story. And at a certain point, I'd written for long enough that I'd practiced my way into a good life. Words helped free me from the delusion that I was doomed. I wrote my way through our story and developed my own authentic voice: I separated us.

One night, after I'd moved back to New York, I had a beautiful dream. Cara and I sat together in a tree house, looking up at the midnight sky. "What if I'm a star hurtling through the atmosphere?" I asked her. She considered my words carefully and then she smiled bright as the moon. "You'll get stardust in your bra," she said, and took both my hands into hers and kissed them. I woke from my dream laughing.

Excerpted and adapted from Her, published by Henry Holt. Copyright © 2013 by Christa Parravani.

-

The 'You' Season 5 Cast Features People From Joe's Past, a New Love Interest, Madcap Twins, and More

The 'You' Season 5 Cast Features People From Joe's Past, a New Love Interest, Madcap Twins, and MoreHere's what to know about the star-studded final installment of the Netflix hit.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

These J.Crew Sale Finds Basically Packed My Suitcase for Me

These J.Crew Sale Finds Basically Packed My Suitcase for MeI'm ready for my next vacation.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

Summer's Sportiest Shoe Trend Is Worth Shopping More Than Once

Summer's Sportiest Shoe Trend Is Worth Shopping More Than Once17 pairs from Nordstrom, Mango, and Zara I'm shopping now.

By Julia Marzovilla

-

More Than A Pretty Face: Anna Schuleit

More Than A Pretty Face: Anna SchuleitGerman-born artist Anna Schuleit went from anonymous to Einstein virtually overnight, thanks to a call from the MacArthur Foundation announcing that she'd won a 2006 "Genius" grant for $500,000.

By Katherine Turman

-

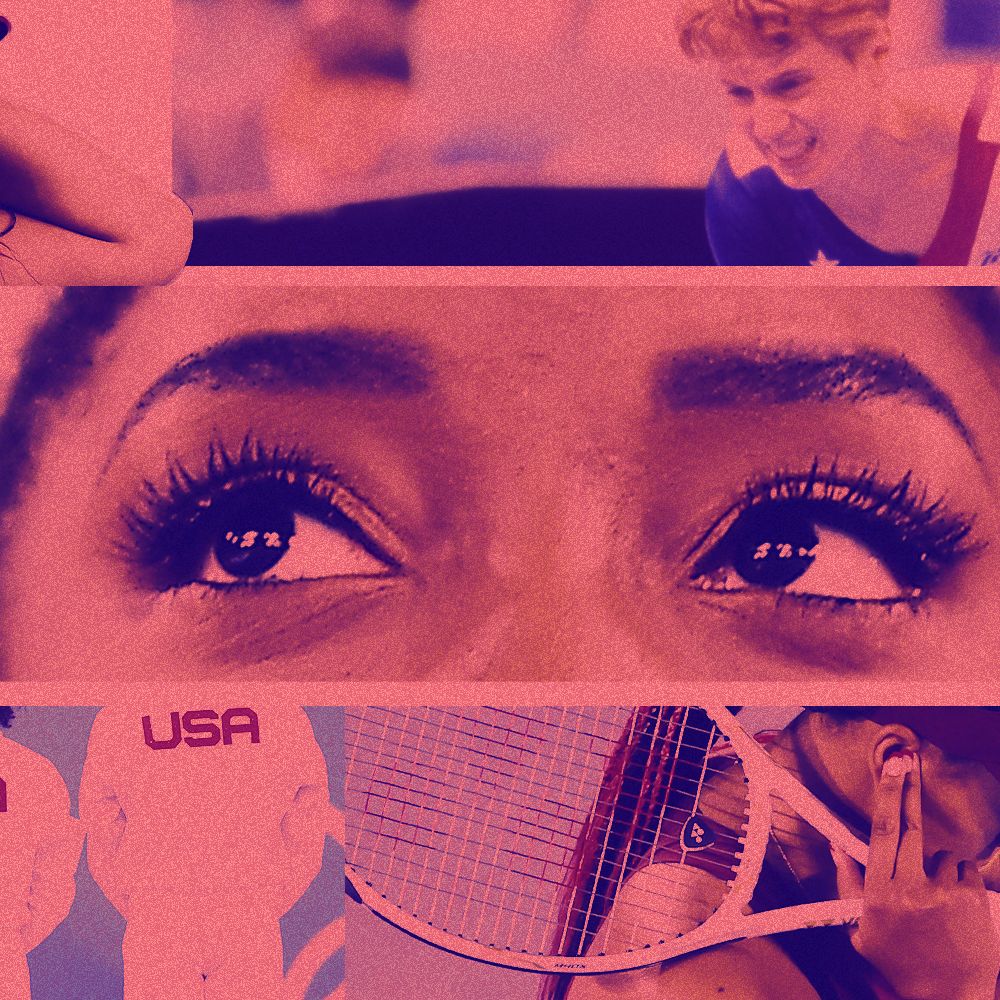

What Makes an Olympic Moment?

What Makes an Olympic Moment?In the past it meant overcoming struggle...and winning. But why must athletes suffer to be inspiring?

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Jessamyn Stanley on Self-Acceptance and the Realities of American Yoga

Jessamyn Stanley on Self-Acceptance and the Realities of American YogaIn her new book, 'Yoke,' the yoga teacher and entrepreneur explores American yoga's link to capitalism, white supremacy, and more.

By Rachel Epstein

-

Simone Biles on Her GOAT Leotard: Don't Be Ashamed of Being Great

Simone Biles on Her GOAT Leotard: Don't Be Ashamed of Being GreatThe world's greatest gymnast shares how she takes care of her mental health, the road to Tokyo, and the story behind her epic new leotard style.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

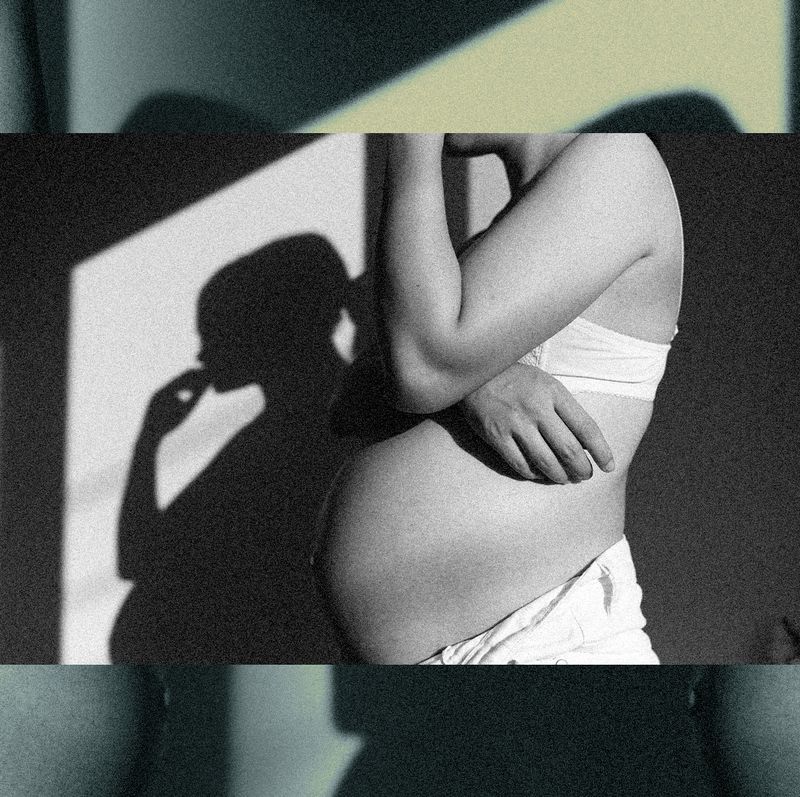

Won't Call the Midwife

Won't Call the MidwifeWith high rates of maternal mortality and coercion in hospital settings, more American women are exploring childbirth without any medical assistance whatsoever. The Free Birth Society provides community, resources, and validation for these convention buckers. But experts warn that choice comes at the expense of safety.

By Rebecca Grant

-

Make Your Micro Wedding All About the Vows

Make Your Micro Wedding All About the VowsNo one wants their lovefest to be a super-spreader event, but they do want it to be extra special. One "vow whisperer" shares how she helps couples—some of them first responders—tie the knot in these troubled times.

By Maria Ricapito

-

The 24 Best Gifts for Weed Lovers That Aren't Corny

The 24 Best Gifts for Weed Lovers That Aren't CornyNo corny pot leaves or dumb puns—promise.

By Cady Drell

-

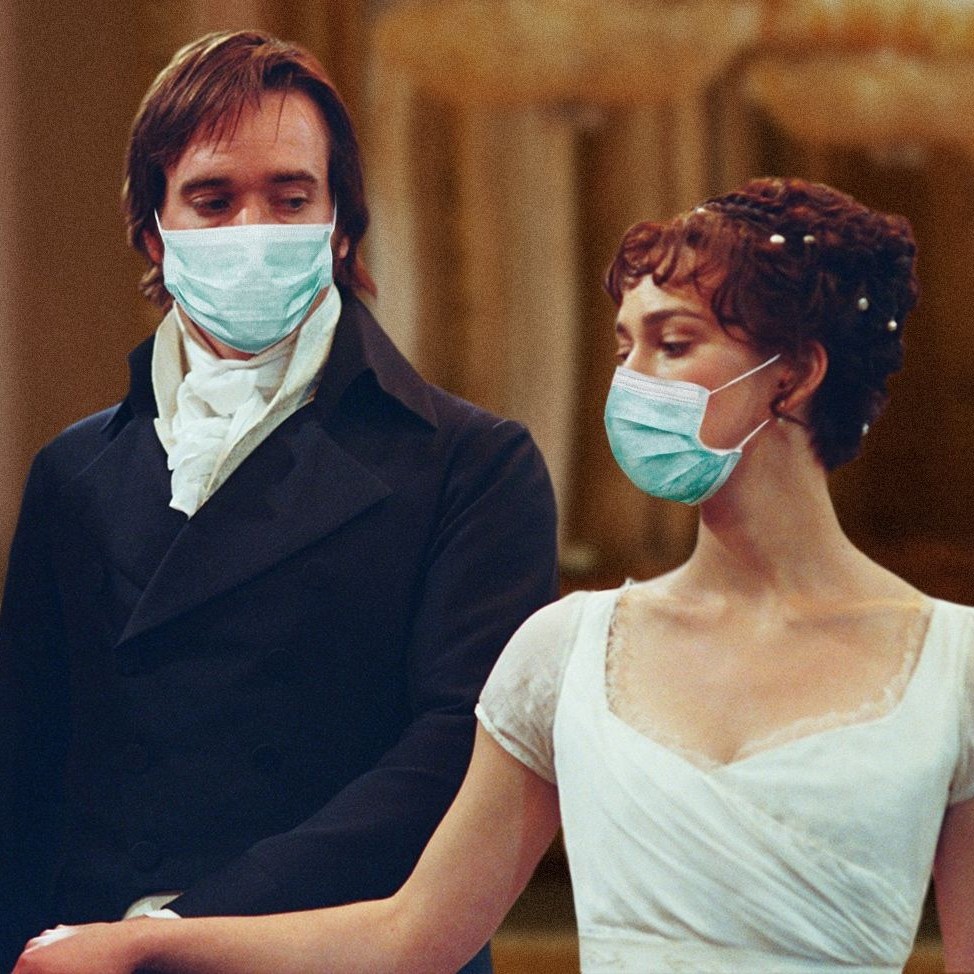

Sense and Social Distancing

Sense and Social DistancingIsolated, socially distant, and unable to touch anyone: The single life under COVID-19 is eerily Jane Austen-esque.

By Jessica M. Goldstein