Sorority Secrets: The Dark Side of Sisterhood That No One's Willing to Talk About

It may be 2015, but Greek life is wreaking havoc in surprising new ways.

When Emma*, a senior at a Southeastern University, was a freshman, a fraternity member recorded one of her pledge sisters having drunken sex with a brother at a mixer and passed the video around his house. The pledge sister didn't discuss the incident with her, so Emma never learned whether the sex was consensual. But her sorority's reaction to the news was surprising: They complained behind the sister's back that she had damaged relations with a high-ranking fraternity, which suddenly didn't want to mix with them anymore.

"I was like, I can't believe she would do this to us. We still wanted to hang out with them because they were a cool, cute fraternity," Emma recalls. "Now I can't believe I thought those words. The sororities inflict values on us, and it's really confusing, so we take it out on one another so we can keep partying." Why would a sorority turn on a member who may have been raped? The answer lies in a sisterhood that is much more complicated than outsiders realize.

Several years ago, I went undercover to investigate sororities for my book Pledged: The Secret Life of Sororities. The reaction to exposing these popular, opaque groups was immediate and fierce. Some sorority chapters banned or boycotted the book; some members tried to publicly shame me online. But for years afterward, my inbox was flooded with emotional thank-you notes from sisters and alumnae—so I decided to connect with the current generation of sorority women to update Pledged (the reissue comes out this month). And this new investigation uncovered something chilling: The National Panhellenic Conference (NPC) sorority system does contribute to campus rape culture.

Sororities hold a powerful allure. When young women arrive on campus, the promise of friends, a fun social calendar, and a home base can be comforting. Sororities can make a large campus feel smaller, giving students a sense of belonging. Many chapters teach leadership, plus organizational and professional skills, and encourage community service. And at some schools, Greek life dominates the social scene.

But there's evidence that sorority members are sexually assaulted at a higher rate than nonmembers; a 2009 Violence Against Women study reported that sorority women at one university were four times more likely to be sexually assaulted than non-Greeks, and a 2014 University of Oregon (UO) study found that nearly one in two sorority members on that campus were victims of nonconsensual sexual contact.

Sorority women at one university were four times more likely to be sexually assaulted than non-Greeks.

It's also well documented that fraternity brothers are more likely to commit rape than non-Greeks. After a Georgia Tech fraternity member's e-mail surfaced in 2013, instructing brothers about "luring your rapebait" by weakening a girl's defenses with alcohol, Oklahoma State University professor of higher education and student affairs John Foubert observed, "The 'rapebait' e-mail could have been sent from almost any fraternity at almost any American college." Foubert's 2007 study found that fraternity brothers are three times more likely to commit rape than non-Greek students. His research team reasoned that the fraternity experience caused students to be more likely to commit sexual assault.

University of Oregon psychology professor Jennifer Freyd, who authored the UO study, says, "When we saw the magnitude of the rates, we were just blown away." Despite her findings and a task force chairwoman's conclusion that "fraternities are dangerous places for women," UO plans to expand the campus Greek system. "There is high demand among students for increased opportunities in fraternity and sorority life," says University of Oregon spokesperson Rita Radostitz. "We have worked on a number of ways to address the concerns around sexual violence. This is nothing new. The issues around sexual violence on campus have been around for 30 years."

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Freyd says, "Fraternity people said horrible things about our research, but we didn't set out to get fraternities. We measured different variables, and this popped right out. I thought the university would be as alarmed as we were, that they wouldn't knowingly expose people to such a thing. But they were completely resistant to halting the expansion. That's when I began to understand the power of the whole Greek system."

Some alumnae sorority leaders maintain this power by silencing members who try to speak out. When Emma wrote a newspaper article about her sorority's confusing messages about sexual violence, her sorority's regional director removed her from her chapter officer position. "They shamed me for writing it. The adviser said, 'This is going to follow you for the rest of your life,' " Emma says. After Kate, a senior in Virginia, told the media that sororities don't empower members to discuss sexual issues, her sorority's alumnae leaders threatened to put her chapter on probation if any members voiced their opinions again. Dismayed, Kate deactivated this year. "I joined the sorority to strengthen my network and because I thought it was supposed to give me a voice, not to be told that I can't speak out." ("National Panhellenics have a policy in terms of how requests from the media are handled. We just want our message to be consistent and to be correct," says Jeanine Triplett, the NPC Student Safety and Sexual Assault Awareness task force chairman.)

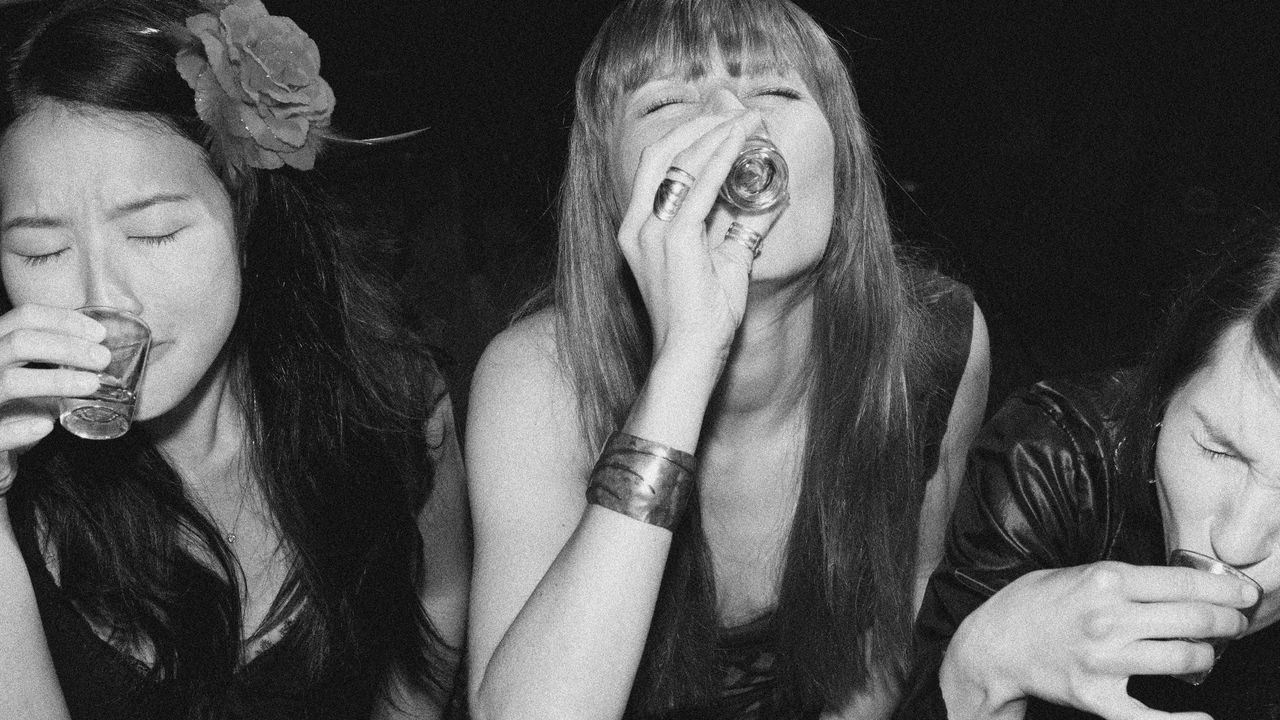

What are sororities trying to hide? Many students told me that after joining their sorority to make friends, they were surprised that they instead were pressured to interact constantly with fraternities. "As soon as I joined, we were pushed to go to all these mixers," says Leah, a sophomore who transferred out of her Pennsylvania school to one without a Greek system. "There was a mixer every night at the beginning of the semester, which was really overwhelming. I wasn't used to going out on a Monday night. I wanted to connect with the girls in a way other than drinking with a fraternity."

Mixers (usually parties for one fraternity and one sorority) are often themed events. Various "bros and hos" themes are popular—Workout Bros and Yoga Hos, for example—but sorority members also told me about "no-pants parties" and "ABC (Anything But Clothes) parties" to which sisters wear bubble wrap, duct tape, or lingerie.

At a series of themed parties at a North Carolina school, new sorority members were expected to help fraternities recruit brothers by dressing provocatively and getting the boys drunk, according to Jess, a 2013 graduate who says she was raped by another school's fraternity member whom she'd dated in the past. Five days after Jess' pledge class joined the sorority, "The sophomores said, 'This is what you do, where you go, what you wear.' We were told to dress as some sort of prize or enticement to these men. I saw someone's dress off completely, people going off into rooms together. It was definitely not a safe environment," she says. "They had this mentality of, We have to impress these guys to increase the reputation of our chapter. Our entire introduction was wrapped up in how promiscuous you could [appear] in that setting." Four of Jess' close friends told her they were raped by fraternity members.

"People say there's not a push to drink or party, but once you join, that's basically all it is. Everyone pressures you to go instead of study."

At a chapter in Tennessee, at least three-quarters of sorority events involve drinking with fraternities, according to Sara, a sophomore. "People say there's not a push to drink or party, but once you join, that's basically all it is. Everyone pressures you to go instead of study." Inside the parties, "If you're sober, they give you a hard time," she continues. "The sorority girls have been like, 'Just take a shot.' The guys will get really touchy, offer drinks. They got me to drink after they kept asking me for an hour. A few times, my sisters have been roofied because of this kind of pressure. One of them was raped."

This is not to say that instructing college women to wear racy getups sets them up for sexual violence, or that the Greek sexual-assault problem is as simple as more alcohol equals more vulnerability. Long-standing research, including a 2009 University of Iowa Center for Research on Undergraduate Education study, shows that Greeks drink more heavily than non-Greeks, and the National Institute of Justice reports that alcohol use is most commonly associated with sexual assault on campus. But the root of the problem is more complex.

Alcohol isn't merely a substance that impairs judgment; it also can be a tool for sexual assault, Freyd says. A few sorority members told me about fraternities that are "known" to slip roofies into drinks, but the women often don't take action because they don't want to rock the boat. When Sara suggested her sorority report an offending fraternity's behavior to the university, her sisters replied, "Our sorority's going to look really lame if we report it, so leave it alone." Rather than avoid interacting with men who promote this culture, and instead of saying, "Don't go," they say, "Don't drink the punch."

Sexual assault is not the sisters' fault; the rapists are to blame and, in some cases, so is the fraternity culture, as exemplified by an e-mail sent last year from a University of Maryland fraternity member who encouraged members to "fuck consent." But one has to question a system that repeatedly sends young women into high-risk environments. Ultimately, the pressure to drink and to impress the guys wouldn't be so overwhelming if sororities didn't push their women into fraternities to begin with.

Sexual violence and related pressures are not problems in every sorority, of course. At a Virginia chapter, a senior told me she knows of no attacks, fraternity parties are open to all sororities, Greeks do not live in houses, and there are no paired social events. And this year, the NPC convened the Student Safety and Sexual Assault Awareness task force, which hopes to provide sororities with a "tool kit" including resources, a hotline number, and guidelines on campus safety.

The task force didn't address the question of why the sexual- assault rate is higher among sorority women. "On college campuses, fraternities and sororities are put in situations where they're very social, and they get to know each other very quickly in group settings. But we didn't study [causes] because it's pretty much out there," says Triplett. "One of our calls to action for National Panhellenics is advocacy, to encourage empowerment on our members' end."

The NPC has a ways to go. A major aspect of Greek life on many campuses involves a courting system in which sororities try to persuade their fraternities of choice (or vice versa) to pair with them for Greek Week or homecoming activities. As a result, some chapters feel obligated to pander to fraternities to score invitations. "There's not much empowerment for sorority women because we have to do things to make sure the guys like us," Emma says. "We have to please them and dress a certain way so they'll invite us to parties."

At a Missouri school, fraternities ask sororities to make videos convincing them to pair, says Morgan, a senior who transferred to a school without Greek life because of sorority pressure. "These videos said, 'We're hot girls, we're party girls, we're down for any kind of partying that you want.' We'd sexually advertise ourselves rather than saying we're smart girls, confident, achievers. We'd show girls drinking at pool parties in their bikinis."

The sisters portrayed themselves this way because "the fraternities like to pair with sororities with attractive girls who they think they can hook up with easier. So the sorority encouraged us to 'go out and drink and see what happens.' It felt like, 'If you hook up with them, they'll like you, and that's what we want.' That was the message the sorority sent," Morgan says. "They required us to go to all these fraternity events to 'support sororities.' If I didn't go, I wouldn't be 'bonding with the sisters.' "

Interaction with fraternity brothers is a membership requirement on some campuses.

Interaction with fraternity brothers is a membership requirement on some campuses. At an Alabama school, sisters recently were fined $15 for every hour of every Greek Week event paired with a fraternity that they missed. Similarly, many sororities have a points system in which sisters must accumulate a total each semester. Several members told me that attendance at mixers and other fraternity events is an expected way to obtain points, in addition to participating in charity events or earning high grades. An Indiana chapter doubles the points for party attendance if the sisters are trying to secure their escort fraternity for a major party week. Amy, a senior there, admits to having pressed sisters to attend fraternity parties: "If only 10 of your girls show up, you insult the fraternity, and then why would they ask you back?" When not enough of her sisters attended a function, the fraternity canceled all future parties the chapters had planned together.

Amy is an unexpected person to pressure sisters to go. When she was a freshman, her chapter's upperclassmen pushed new members to attend a mixer hosted by a fraternity reputed to sexually assault women. A fraternity member got Amy's pledge sister drunk and slipped something into her drink, Amy says. Even though the sister was then raped, the sorority continued to pair with the fraternity. Two years later, Amy says she was assaulted by a different fraternity member, who was subsequently suspended by the university following an investigation. Many of his brothers remain upset with Amy, but she doesn't want her sorority to stop socializing with them. "Most fraternities wouldn't pair with us because we're a bottom sorority; top-tier fraternities only pair with top-tier sororities," she explains. "We do not pair outside our tiers. If you're only pairing with five or six fraternities, cutting one out would cut out a lot of your social schedule."

As in other aspects of higher education, much of Greek life has zeroed in on rankings. Many sorority sisters can recite which groups are top-, middle-, or bottom-tier chapters. Sites such as greekrank.com and the Yik Yak app contribute to the frenzy. "Rank is based on attractiveness and your party-hard mentality," Morgan says. Because sororities' tiers can depend on how much fraternities like them, developing a relationship with a higher-tiered fraternity can improve the sorority's rank.

These types of priorities are causing some sisters to struggle with their membership, says Becky, a junior in a North Carolina sorority. "It's sad because people think it's the girl's job to defend herself and if she drinks the punch, that's her fault—instead of the sorority's fault for planning the mixer with that fraternity," she says. "It's the system of everyone having to keep up this image that they're the best, the prettiest, the most fun. It's exhausting, actually. I like my sorority, but I don't like the system."

Many sororities' national offices indirectly encourage this ultimately dangerous emphasis on image because the students believe they are overly focused on recruitment. Members say that the national offices ("Nationals") judge chapters by recruitment numbers and can threaten to shut down groups with weak turnout. (While Triplett says few chapters have closed recently because of membership, she explains, "Oftentimes, it comes down to a financial situation. It is a business.") That's what happened to Nina's Indiana sorority chapter several years ago: Because they didn't recruit enough members, an alumnae representative told the sisters they were "complete failures" and Nationals closed the chapter.

Now Nina is one of several advisers for that chapter, which recently reopened. (Chapter advisers are unpaid adult volunteers who counsel on issues such as finances, recruitment, and philanthropy.) "There's a total fear that if we don't live up to Nationals' standards—not getting the numbers we need, the 'quality' girls they're looking for— they'll close the chapter," she says.

That fear explains why concern over a chapter's reputation can lead sisters to do things they might not otherwise do. Nina's chapter "serenaded" several fraternities this semester, which on that campus means new members danced for and grinded on the brothers. "They did it because that's what the other houses do. When my chapter did it, we did the 'Thriller' dance. Now everything's sexualized. It's very raunchy and inappropriate," Nina says. But she understands why the girls felt like they had to do it. "You want to be in a sorority so badly, you're willing to give yourself up for it. If you're out getting drunk every night at the fraternity, they're going to like you. They want guys to tell people they're fun because they think they'll do better in recruitment."

The NPC attributes sisters' emphasis on fraternity interaction to "peer pressure" and "wanting to be accepted, so they'll go along and do whatever," Triplett says. "We don't require our women to go to fraternity parties, but it's a long culture on so many campuses."

Like Nina, Deb, an adviser in Virginia, says she feels "caught in the middle" between her national office's expectations and what she believes is best for her students because "the focus is being placed too heavily on who we hang out with rather than what we stand for," she says. "I have to deal with some issues in Nationals' way, like making sure mixers are with 'quality' fraternities in good standing with the university. That says nothing about the guys' personalities. When I was a [student], at chapter meetings they told us we needed to hang out with the cool fraternities. I said, 'Why would I want to hang out with a fraternity who doesn't treat women right?' As an adviser, I know now: Collegiate women attend fraternity functions, which may promote risky behaviors, because it helps improve the sorority's image."

That's the major reason why many college women defy their better judgment, make excuses for fraternities, and keep returning to the scenes of the crimes. It's why Emma turned on a sister who might have been raped. "Girls blame other girls because we're obsessed with the rankings," she says. "It disgusts me now. The oaths we take aren't being upheld because of the focus on fraternities."

"Girls blame other girls because we're obsessed with the rankings."

The NPC "does not endorse tiers," and associating ranking with reputation is "focusing on the wrong thing," Triplett says. "If a chapter has excellent grades and leaders in campus organizations, that is what will bring a strong reputation. If they really think hanging out with a popular fraternity will make their reputation, that won't last."

If NPC officers are espousing these messages, there's a disconnect between the adults and the many students they oversee. Even Triplett admits that it can be "challenging" to govern such an enormous membership (of more than 4 million), "especially when you fight against campus culture."

Many sisters remain in the system regardless of the risks, because, as Amy says about her Indiana chapter, "The alumnae, social networking, and lifelong friendships and memories make it worth it." Women told me that their Greek experiences enhanced their collegiate lives, got them involved in philanthropy, and prepared them for successful careers in government and marketing. Sororities have plenty enough going for them that they shouldn't need fraternities to define them. But if Nationals are unwilling to undertake the progressive overhaul necessary to make these groups about women, there's still a way to keep the benefits without eliminating Greek life: Nationals could cede authority to universities—who are accustomed to navigating their own campus culture—and pay them to supervise fraternities and sororities like any other student club. If Greeks no longer worry that their chapter's existence relies on recruitment numbers, they'll be less concerned about their tier because the stakes won't be as high.

Until then, the cycle continues: Some sorority leaders pressure chapters to perform well during recruitment and to interact with fraternities. Sisters urge one another to party with fraternities to keep up their reputation, which they believe affects recruitment. "There are discussions about not going because it's dangerous, but some people argue, 'If we didn't get hurt this time, it's not a problem' or 'It's a good fraternity and the roofie-ing is just made up,' " says Sara. "But we know it's not."

*The college women and advisers I interviewed are given pseudonyms for fear of reprisals from their chapters. Additional reporting by Lane Florsheim.

This article appears in the August issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

-

I'd Be a Bad Friend If I Didn't Put These 3 Spring Trends on Your Radar ASAP

I'd Be a Bad Friend If I Didn't Put These 3 Spring Trends on Your Radar ASAPYes, florals made the cut.

By Kaitlin Clapinski Published

-

Florence Pugh Is a Daring Red Carpet Trend's Favorite Poster Girl

Florence Pugh Is a Daring Red Carpet Trend's Favorite Poster GirlShe loves a see-through look.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

Princess Kate Might Be Heading to South America This Fall After Major Palace Announcement

Princess Kate Might Be Heading to South America This Fall After Major Palace AnnouncementFingers crossed.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

The 100 Best Movies of All Time: The Ultimate Must-Watch Films

The 100 Best Movies of All Time: The Ultimate Must-Watch FilmsWe consider these essential viewing.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)

The Best Bollywood Movies of 2023 (So Far)Including one that just might fill the Riverdale-shaped hole in your heart.

By Andrea Park Published

-

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We Know

‘Bachelor in Paradise’ 2023: Everything We KnowCue up Mike Reno and Ann Wilson’s \201cAlmost Paradise."

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?

Who Is Gerry Turner, the ‘Golden Bachelor’?The Indiana native is the first senior citizen to join Bachelor Nation.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

The 50 Best Movie Musicals of All Time

The 50 Best Movie Musicals of All TimeAll the dance numbers! All the show tunes!

By Amanda Mitchell Last updated

-

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We Know

'Ginny & Georgia' Season 2: Everything We KnowNetflix owes us answers after that ending.

By Zoe Guy Last updated

-

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your Guide

The Cast of 'The Crown' Season 5: Your GuideFeatures The Mountbatten-Windsors have been recast—again.

By Andrea Park Published

-

Who Is Hasnat Khan, Princess Diana’s Boyfriend on Season 5 of ‘The Crown’?

Who Is Hasnat Khan, Princess Diana’s Boyfriend on Season 5 of ‘The Crown’?Features Di’s friends have said she referred to the doctor as \201cthe love of her life.\201d

By Andrea Park Published