Who We Love: Georgina Chapman

The Marchesa designer and cofounder raises awareness for the plight of Syrian refugees

In just overthree years, more than 2.9 million Syrians (three-quarters are women and children) have been driven from their homeland because of the country's internal conflict. So when English author Neil Gaiman asked Marchesa's Georgina Chapman to accompany him on a two-day trip to Jordan to collaborate on a storytelling project, she didn't hesitate in saying yes. In May, along with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), they traveled to two camps—Zaatari, home to more than 80,000 refugees, and Azraq, established this spring—to record video footage of the work that UNHCR and its partners are doing, from distributing food and water to providing health care and schooling. "It can be hard to identify with those affected by humanitarian injustices overseas—but they are just like us," Chapman says. "They feel love, loss, trauma, tragedy, and hope exactly the same way we do." A particularly affecting moment was seeing children at a play center. "Two weeks prior, they were drawing images of bloodshed and weapons," she recalls. "Now they are drawing hearts and flowers. The resilience of the human spirit filled me with optimism." Chapman plans a return trip to Jordan to document more stories from the camps: "They speak to the very core of who we are as humans. It's about our sense of family, home, safety, and identity."

Georgina recounts her trip to the Syrian refugee camps in Jordon.

DAY 1 – 13 MAY 2014

I'm here in Jordan with the UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency, writer Neil Gaiman, and my husband Harvey Weinstein. Our purpose is to raise awareness for the Syrian refugees. The more-than-three-year Syria Crisis has driven millions of women, children and families from their homes to escape violence, death and destruction. In Jordan alone, nearly 1 in every 10 people is a Syrian refugee. As such, I don't know what to expect on my first day here. I don't have any preconceived ideas coming into this mission because it's so foreign to anything I've ever experienced, or imagined experiencing.

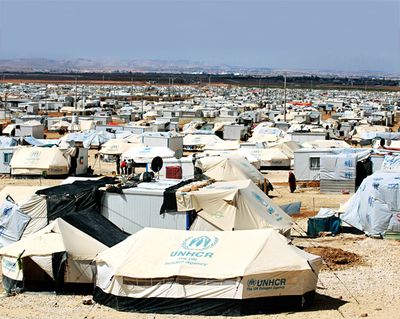

Just after dawn we headed to Zaatari refugee camp. What struck me most is how normal life seems—how incredible and self-sufficient everyone is. They've built this sort of city in the middle of the desert, and it's full of vibrant people who are setting up enterprises like baklava stalls, beauty salons, grocers, clothes shops, and little restaurants. There's an amazing spirit, which I find so enlightening.

But at the same time, amidst all the bustle, I remembered the undercurrent of terrible sadness that people are working through. Every family we encountered has a heartbreaking story of horror. I heard stories of parents digging their children out of rubble, of fathers taking bullets in their backs while trying to save their families, and of those searching for their disappeared loved ones. The lives of these people have been so damaged, and these children have been so traumatized. This reality struck me when Neil and I visited a classroom of young adults being taught English. One of the men in the classroom suddenly started crying while speaking about his brother, who had been lost trying to enter Jordan. There was also a university student who had been working to get his doctorate in archaeology before the crisis began. This felt so tangible to me—that it could have been me at that age, trying to get my degree with a bright future full of possibilities lying ahead. In this moment I realized that while these young men and women are now in a safe haven, they are living in a terrible state of limbo; they can't settle yet they can't leave, they can't work and they can't really continue their studies. Their future is utterly uncertain, and this must make it so difficult to be hopeful. Yet despite that, there is this amazing sense of resilience in the camp because there is such strength in the people.

A refugee boy in front of a transitional shelter in Azraq. The units were specifically designed to address housing concerns in Zaatari.

Chapman and Neil Gaiman (far right) help a family collect water.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

A view of the Zaatari camp, which houses more than 80,000 refugees.

Marchesa's Georgina Chapman (right) speaks with a Jordanian UNHCR staff member.

DAY 2 – 14 MAY 2014

Today was very different. When Neil, Harvey, and I first turned up at Azraq camp, we were a bit shocked at the difference from yesterday's camp. Azraq only opened very recently and compared to the bustling life and activity of Zaatari it felt eerily quiet, and the barren and rocky desert landscape felt less hospitable. Thankfully, that quickly changed once we started meeting the refugees who now live here, all very recent arrivals.

We met one family of around 30 brothers, cousins, wives and children who had literally crossed the border into Jordan hours before. They kindly agreed to share their stories with us. The men recounted not just their journey to the camp, but also talked of their experiences back in Syria. They had been displaced inside Syria for nearly three years, moving from village to village to avoid the fighting, and their stories were raw and shocking. They talked about having no option but to eat dogs, cats and leaves to survive. They talked about walking through body parts while crossing the border, and about nearby families who were shot and killed on the road out. It was very surreal and yet very real at the same time. I cannot imagine what they are thinking or what they are feeling. I think one of the wives felt angry that her family is in this situation. It was a very heavy-hearted morning.

In the afternoon, the mood shifted. We went to a children's play center in the camp and the children were incredible. We learned that just two weeks prior, they were drawing images of bloodshed and weapons. But now, in this safe space, they are drawing hearts and flowers and are laughing. It was unbelievable to see first hand the resilience of the human spirit. It filled me with such a sense of optimism, but also of real concern for the children of Syria, this potential lost generation who has witnessed such horrors and whose lives, education, family units, and childhood memories have been so broken. And yet, we can all do something to help safeguard their chance of a promising future. This is such a compelling part of UNHCR's work.

Before we left Azraq, we met a man whose story impacted me greatly. He recounted his life in Syria, where his village had been torn apart by the oppressors. The violence he spoke of was truly unfathomable: he had witnessed grotesque forms of torture and barbaric killings. His experiences with those in uniform were those of horror and fear. As he continued his story, he spoke of crossing the border from Syria into Jordan. He mentioned that when he saw the Jordanian army, his immediate instinct was one of terror. But as he spoke of the army taking his bags, and giving him food, water, and shelter, he broke down into tears of gratitude and relief. What struck me most in that moment is that the kindness of the human spirit brought him to tears, not the atrocities he had experienced in Syria. This was one of the most moving parts of this trip so far.

Despite the darkness of so many of the stories we have heard and the unbelievable loss and pain, Neil, Harvey, and I are inspired by the strength and courage of the human spirit and the generosity of heart that somehow still exists inside the refugee families. Despite having next to nothing, they are doing all that they can to provide for themselves so they are not a burden. It is impossible for them to restart their lives totally on their own and they need the support of UNHCR. But the UNHCR can't do it alone either, as it is drastically underfunded. It desperately needs our support to continue providing lifesaving care and assistance to Syrian refugees.

Syrian refugee Um Murad, the sole breadwinner in her family, runs a successful beauty salon and wedding dress rental business in Zaatari.

Food for thought: Bread is distributed daily to each refugee family.

For more information/how you can help: www.unhcr.org/neilandgeorgina

Photos via Getty Images/UNHCR/Kalpesh Lathigra/Jordi Matas