Eva, Everlasting

The actress’s career has been in overdrive for decades. As she approaches turning 50, the Hollywood mainstay gets personal about why she’s still not slowing down.

Years ago, when Eva Longoria was starring in Desperate Housewives as the impulsive and outrageous Gabrielle Solis, a skeptic wondered whether she risked getting pigeonholed for choosing roles that so overtly emphasized sex and romance. She was too beautiful, too sexy, too much. No actor could sustain that level of heat forever. In the parlance of our current moment, it would behoove her to be a little more demure. Best if she covered up.

But Longoria isn’t one to take direction from detractors. Recalling the criticism now, Longoria arches a brow: Was she not supposed to want to be hot? She swerved in the other direction. Riding her particular wave of fame “to the beach,” she accepted offers to pose for men’s magazines with zeal, even as she became a respected powerbroker in liberal political circles. She preened in bikinis and fundraised for the causes she believed in. She concealed the bare minimum with well-placed props. She made the most of it.

Still, in dressing rooms and changing tents, she too, wondered whether these kinds of shoots had an expiration date. But her makeup artist reminded her to focus on the present. “She went, ‘Honey, do them now,’” Longoria recalls. “‘Because you’re not going to do them when you’re 50.’”

In four months, Eva Longoria will be 50.

When we meet at the Beverly Hills Hotel in late September, Longoria is wearing fresh New Balance sneakers, has her hair swept into a ponytail that bounces and twirls like it should have had its own floor routine at the Paris Olympics, and speaks at such a rapid clip that I believe her when she tells me she could run a marathon right now if she wanted to. She has just landed in Los Angeles after months in Mexico and Spain, and jet lag is quite apparently no match for the stamina she has spent years cultivating.

There are women who dread the aging process, and those who make their tentative peace with it, and then there is Longoria—the kind of actor who is never late to set, the kind of director who once made a pitch deck so impressive that a competing candidate for the gig had no choice but to concede he would have hired her too, the kind of person who has been preparing for this milestone like some people train for extreme sports.

“I’m cold-plunging; I’ve got red lights on; I strength train with weights; I meditate; I’m journaling,” she tells me, enumerating her wellness practices. “I wake up with the sun; I’m doing the grounding; I have an Oura ring to track deep sleep; I’m taking magnesium and other supplements; I’m doing everything. Not because I don’t want to age but because I do want to age.”

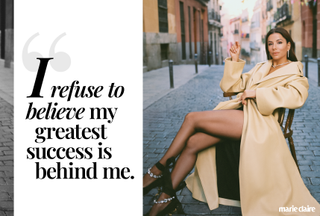

The post-50 careers of women like Gwyneth Paltrow and Jennifer Lopez are a beacon for her, as is the sweet validation that she feels now, remembering all the people who once predicted she would flame out. “For me, age is just a number, but I’m excited,” Longoria continues. “I refuse to believe my greatest success is behind me.”

So of course when she thinks back to the conversations with her makeup artist and to the roles that required her to take her clothes off, she knows she can declare now what she couldn’t have then: “I’m like, ‘I would totally do that photo shoot at 50.’”

Jacquemus skirt and top; Joyas Antiguas Sardinero necklace; Magrit boots

Round numbers get all the attention, but 49 was a banner year for Longoria too. In March, she walked the Oscars red carpet after her directorial debut Flamin’ Hot earned a nomination, having already clinched the title of Searchlight Pictures’ most-watched streaming movie of all time. In April, she joined Siete Foods as an investor and advisor. It has since sold to PepsiCo for $1.2 billion. She soon jetted off to film Searching for Spain, the follow-up to her acclaimed CNN miniseries Searching for Mexico, which found her sampling the best of the country’s beloved cuisine—and showcasing its sometimes misunderstood culture in the process. (Stanley Tucci inaugurated the series with two seasons of his own Searching for Italy.) In June, Longoria starred in the Apple TV+ series Land of Women (which she also executive produced). A few months later, she popped up for an uproarious arc on the new season of Only Murders in the Building on Hulu. Somehow, she also found time to speak at the Democratic National Convention, release a second cookbook, be honored at the annual Día de Muertos Gala, and hit the trail for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz (but more on the election in a minute).

Hermès coat top, shirt, pants; Mimoki hat; Aquazzura shoes

Amid the palm fronds in Los Angeles, she laughs as she recounts this recent sprint of work. Some of the latest projects to populate her IMDb shot at once, necessitating an intense travel schedule and at least one wig. When she wrapped them, Longoria was exhausted, gratified, and on no discernible circadian clock.

As in wellness, so too at work—she wants to do and taste and experience it all. One of her few recurring anxieties is that there are places on this wondrous planet she will never visit. “I get depressed thinking I’m not going to see it all before I die,” she says. “That makes me sad. I’m like, I know I’m going to Africa, but I’m not going to get to go to all of Africa. I know I’ve been to South America, but I’m not going to be able to see all of South America.”

So no wonder that when people come calling with opportunities, especially those that will take her to new landscapes, Longoria defaults to yes. She wants to be out there, doing. “‘She’s available,’” Longoria tells me, repeating the response she tells her agent to give to the flood of overtures she gets to act, to donate, to produce, to fund. “[People] are like, ‘Isn’t she shooting right now in Atlanta?’ ‘She’s available.’”

The truth is multitasking suits her. When Longoria first moved to Los Angeles from Corpus Christi, Texas, in her twenties, she kept a job as a corporate headhunter even after she snagged a role on The Young and the Restless. While Desperate Housewives aired and Longoria entered her thirties, she decided to earn her master’s degree in Chicano Studies from Cal State at night. Twice a week, she’d take classes from 7 p.m. until 10 p.m., heading back to set the next morning before sunrise. So perhaps it’s not a surprise that she was never going to stick to acting. After Desperate Housewives wrapped, Longoria joined its creator’s next show Devious Maids as an executive producer. She was tapped to direct an episode of the series and went on to direct episodes of Jane the Virgin, starring Gina Rodriguez, The Mick, and Black-ish. When I last spoke to Longoria in 2020, she explained that she wasn’t one of those actors who discovered directing. She was a born “producer and director who fell into acting.”

Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello top, skirt, tights, belt, earrings, bracelets, and shoes; Guante Varadé gloves; Stylist's own shawl

Another network TV star turned filmmaker, George Clooney has known Longoria since they met on the Warner Brothers lot decades ago, where he maintains that “it was impossible not to notice her.” The two have since traded notes on how and when to navigate making the switch from roles in front of the camera to ones behind it. And while he would never presume to give her advice, “we did talk much earlier about being in charge of your career—not just relying on what some producer thinks of you as an actor, having more say in the work you do, whether that’s producing or writing or directing,” Clooney writes in an email.

Clooney and Longoria have fundraised together and connected over their mutual involvement in political activism. He is adamant that in that time he has been more fan than mentor. “She kicked ass,” he continues, referring to her work on Flamin’ Hot, the perhaps-not-true-but-still-addictive tale of Richard Montañez, the Mexican-American janitor reputed to have invented the iconic Cheetos flavor. “Talent doesn’t sustain you in this business. It requires hard work, determination, and brass balls. We know countless stars who flamed out. The reason she’s still so relevant is because she won’t take no for an answer.”

Guilty, Longoria tells me. She is as relentless as Clooney says. “I say if I get a no for something that I really want a yes for, I’m always [like], ‘Okay, I’m asking the wrong question or I’m asking the wrong person,’” she says.

Practically, that approach means that Longoria ends up handling much of what someone else might deputize her team to do. Cris Abrego, who launched the production company and talent agency Hyphenate Media Group with Longoria, has watched her in action. “Eva picks up the phone,” he says. “We don’t call people and say, ‘We’re calling on behalf of Eva Longoria,’ because nine times out of 10, she’s calling herself.”

When Longoria wanted Becky G to sing the Diane Warren-penned “The Fire Inside,” which scored Flamin’ Hot its Oscar nod, she made a personal call to pitch the singer on the project. “It was a no-brainer,” Becky says now. “Eva knew my story better than anyone—how I used to sell Cheetos in school—so when I saw that a powerful Latina woman was putting a spotlight on someone from our community as the hero, that doesn’t happen so often. I was all in.”

Later, Longoria volunteered to direct Becky in the music video as well. “I got to experience her as the shot-caller,” Becky says. “She’s been in this industry for so long, and watching her work like that was so inspiring. For her to take me under her wing is something I’ll never forget. Who wouldn’t want to learn from someone like her?”

Loewe coat; Bulgari earrings and necklace; Christian Louboutin shoes

Longoria’s pointillist-level attention to detail paid dividends. Flamin’ Hot became “a four-quadrant movie”—insider speak for films that appeal to both men and women, under and over the age of 25. “People were like, ‘I saw it with my mom and my 17-year-old son and my grandma,’” she says. “Young, old, white, Hispanic, Black, Asian, female, male—I made the movie for my community, but everybody loved it.”

It’s the ultimate aim for her work. Can she create something so good and compelling that even unlikely audiences are drawn in? That’s part of what motivated her to do Searching for Mexico. She hoped it could bring disparate groups of people together under the guise of entertainment. “I feel like the strained relationship between us and Mexico needs to be repaired, and I think culture and food can easily celebrate the best things of a country,” Longoria says. “The people who were screaming, ‘Build that wall!’ are the same people that are going to Taco Tuesday. And I’m like, ‘No, no, no. You don’t get to margarita out and shit on the culture that gave you the taco and gave you the margarita. You have to go, ‘This came from there. There must be good things.’”

Even weeks before the election, the sentiment sounds utopian. But when Longoria and I catch up after Donald Trump has secured a second presidential term, it seems hopelessly quaint.

In 2016, Longoria took to her bed after Trump prevailed. “I’ve never been depressed in my life,” she recalls. In addition to actual, bodily anguish, she felt serious doubt about convictions that had once felt undeniable. “It was like, ‘Does my vote really matter? Am I really making a difference?’” she says. “I was so untethered to the core of what I believe because I truly believed in my soul that the best person wins. And then that happened, and I was like, ‘Oh, wait. The best person doesn’t win.’”

Gucci jacket, top, and pants; Bulgari earrings

This time, she didn’t feel quite so floored. “The shocking part is not that he won,” she says two days after the race is called for Trump. “It’s that a convicted criminal who spews so much hate could hold the highest office.” Longoria spent the better part of this past summer campaigning for Kamala Harris. She rallied volunteers with Tim Walz. Countless celebrities endorsed the Democratic ticket, but Longoria is more than a famous surrogate. The Washington Post has called her a genuine “political power broker” for the “fierce and productive” work she has done to organize women and Latinos. The Texas Tribune profiled her efforts to recruit and support Hispanic Democratic candidates up and down the ballot. It’s been less than 24 hours since Harris conceded when Longoria calls me, and it’s obvious that she is still processing the loss. “I would like to think our fight continues,” she says. But she can’t pretend she knows what’s coming next. The country “is a scary place,” she continues. “If he keeps his promises, it’s going to be a scary place.”

For years now, Longoria has spent most of her time outside of Hollywood. She and her husband José Bastón, with their son Santiago, 6, are split between Spain and Mexico. Work takes them from Europe to South America and back. The movie and television business is in flux, but the globalization of it at least suits her. Longoria doesn’t tend to shoot in Los Angeles, and she doesn’t miss it.

“I had my whole adult life here,” she says, gesturing around her. “But even before [the pandemic], it was changing. The vibe was different. And then Covid happened, and it pushed it over the edge. Whether it’s the homelessness or the taxes, not that I want to shit on California—it just feels like this chapter in my life is done now.”

“I’m privileged,” she adds later. “I get to escape and go somewhere. Most Americans aren’t so lucky. They’re going to be stuck in this dystopian country, and my anxiety and sadness is for them.”

Still, no matter her primary address, she continues to identify as a patriot completely, with all the associated baggage we carry. How could she not? Her family has been in Texas for nine generations. America might be battered, but Longoria knows intimately that you can be disappointed in something and still believe in it. She works in the entertainment industry.

Christian Dior dress; Guante Varadé gloves

Earlier this year, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and his fiancée Lauren Sánchez (who remembers interviewing Longoria in her previous life as a journalist) named Longoria a recipient of their annual Courage and Civility Awards, a prize that comes with $50 million to spend on the charities of her choice.

In Longoria-like fashion, Bezos and Sánchez called her themselves to deliver the good news, with Sánchez name-checking a recent speech Longoria had delivered in which she called for more investment in women and communities. “Her words about empowering women and giving them a voice really hit home for me,” Sánchez says. “I was almost moved to tears. She always came across as smart and strong, but hearing her that day, I realized this woman is going to make a huge difference in the world.”

Longoria is planning to use the funds to boost the causes in which she has long invested. She is also responding to the sudden influx of calls she’s gotten to “save iguanas and trees” with as much grace as she can muster. She founded her own grant-giving organization “because I was getting a thousand invitations a week—dolphins in Japan, AIDS in Africa, sex trafficking in Thailand,” as Longoria puts it. “And I was like, ‘Oh my god, yes, the dolphins need help. AIDS—we should find a cure.’ I realized I wasn’t making a dent anywhere. We were spread so thin. So I was like, I need to get specific on who I want to help. I knew it was going to be women, and I wanted it to be Latinas—the women who raised me. And then looking at the barriers to economic mobility, it’s mostly education, culture, and political advocacy, so I decided, let’s do these three buckets.”

That kind of decisiveness has driven Sánchez to clarify her own priorities. “She’s inspired me to be more vocal and involved in supporting our community,” Sánchez says. “She motivates me all the time.”

Schiaparelli dress

Longoria is exceptionally conscious of how much work there is to be done. Well before pollsters were tweaking their election models, Longoria was sounding the alarm to the party elite that Latinos were increasingly sour on the economy and susceptible to conservative appeals. “We’ve been screaming from the highest rooftop that the Latino vote is not something to take for granted,” she says. “You have to earn it and win it every election cycle.” She is already strategizing how candidates in future elections might reverse the trend. “I want to know how we can communicate that government and politics affects your life, whether you like it or not,” she says. “Either you participate in that or you let somebody else hold the power.”

She learned that lesson years ago. Now she finds herself teaching it, and not only to elected officials and political leaders, but to the women in her own industry. The status quo will prevail until people upend it. Executives will tell the same stories until women and people of color decide to tell new ones. “Gina Rodriguez directs because I was like, ‘Listen to me! Get behind the camera!’” she says. “America Ferrera, Lana Parrilla—anybody that wants to come and hear my spiel, I’m like, ‘Yes.’”

Longoria doesn’t pretend it’s easy. After a glut of production in the pre-pandemic years, streamers have started to cut back. And when that happens, “studios go, ‘Let’s just tap into the same well that we have always tapped into for talent.' And that’s unfortunate for women, for people of color, for any marginalized community,” Longoria says. She only knows one way to contend with the odds.

“I show up on time,” Longoria says. “I show up prepared. Our industry is famous for specifically men failing up. It’s like, ‘He got that movie? Didn’t he just… The last movie, he just…? Didn’t that bomb? And they give him another [chance]. That’s great, but I couldn’t do that. I don’t get a second chance. I think for me, there’s no better position than to be underestimated because then you can always over deliver. I’m comfortable outworking anybody in the room.”

Photographer Félix Valiente | DOP Pascal Chahín Martin | Stylist Enol Blasco | Hair Stylist Jesus De Paula | Makeup Artist Iván Gómez | Manicurist Lucero Hurtado | Production NM Productions | Locations Thompson Madrid, by Hyatt; La Fisna Wine Bar; Café Barbieri

Mattie Kahn is a writer who lives in New York. She covers politics, style, culture, and dangerous women. As far as she's concerned, candidates come and go, but the Oxford comma is forever.

-

Katie Holmes Tames an Underrated Animal Print Trend

Katie Holmes Tames an Underrated Animal Print TrendTiger is the new leopard.

By Kelsey Stiegman Published

-

Taylor Swift's Beloved Red Lipstick Is Finally Back in Stock

Taylor Swift's Beloved Red Lipstick Is Finally Back in StockIt's been a long time coming.

By Halie LeSavage Published

-

I Move Up a Tax Bracket Every Time I Wear This Opulent Manicure

I Move Up a Tax Bracket Every Time I Wear This Opulent ManicureBonus: you can achieve the look with $15 press-on nails.

By Samantha Holender Published