'Crying in H Mart' Is Our May Book Club Pick

Read an excerpt from Michelle Zauner's memoir, here, then dive in with us throughout the month.

Welcome to #ReadWithMC—Marie Claire's virtual book club. It's nice to have you! In May, we're reading Michelle Zauner's Crying in H Mart, an expansion of Zauner's viral New Yorker essay in which the indie rockstar grapples with her mother's death and how it shaped her identity. Read an excerpt from the memoir, below, then find out how to participate in our virtual book club here. (You really don't have to leave your couch!)

When I found out my mother was sick, I’d been out of college for four years and I was well aware I didn’t have much to show for it. I had a degree in creative writing and film I wasn’t really using. I worked three part-time jobs and played guitar and sang in a rock band called Little Big League that no one had ever heard of. I rented a room for three hundred dollars in North Philly, the same city where my father grew up and from which he eventually fled to Korea when he was around my age.

It was by sheer coincidence I’d wound up in Philadelphia. Like many a kid trapped in a small city, I felt bored and then suffocated. By the time I was in high school, the desire for independence trailing a convoy of insidious hormones had transformed me from a child who couldn’t bear to sleep without her mother into a teenager who couldn’t stand her touch. Every time she picked a ball of lint off my sweater or pressed her hand between my shoulder blades to keep me from slouching or rubbed her fingers on my forehead to ward off wrinkles, it felt like a hot iron puckering against my skin. Somehow, as if overnight, every simple suggestion made me feel like I was overheating, and my resentment and sensitivity grew and grew until they bubbled up and exploded and in an instant, uncontrollably, I’d rip my body away and scream, “Stop touching me!” “Can’t you ever leave me alone?” “Maybe I want wrinkles. Maybe I want reminders that I’ve lived my life.”

College presented itself as a promising opportunity to get as faraway from my parents as possible, so I applied almost exclusively to schools on the East Coast. A college counselor thought a small liberal arts school, especially a women’s college, would be a good fit for someone like me—captious and demanding of inordinate attention. We took a college trip and visited several schools. Bryn Mawr’s stone architecture upright against the early signs of East Coast autumn seemed to measure up soundly to the ideal image of what we had always imagined a college experience should be.

It was somewhat of a miracle that I managed to get into college, having just barely graduated from high school. Senior year I had a nervous breakdown that resulted in a lot of truancy and therapy and medication, and my mother convinced all of it was a direct attempt to spite her, but somehow I managed to come out on the other side. Bryn Mawr was good for both of us, and I’d even graduated with honors, the first in my immediate family to obtain a college degree.

I decided to stick around Philadelphia because it was easy and cheap and because I was convinced Little Big League might someday make it. But it had been four years now and the band had neither made it nor shown any real sign of spurning anonymity. A few months back I’d been fired from the Mexican fusion restaurant where I’d waitressed for a little over a year, the longest I’d managed to hold on to a job. I worked there with my boyfriend, Peter, whom I’d originally lured there in a long-game play to woo myself out of the friend zone, where I’d been exiled seemingly in perpetuity, but shortly after I finally won him over, I was fired and he was promoted. When I called my mom for a little sympathy, incredulous that the restaurant would fire such an industrious and charming worker as myself, she replied, “Well, Michelle, anyone can carry a tray.”

Since then I had been working three mornings a week at a friend’s comic shop in Old City, the other four days as a marketing assistant for a film distributor at an office in Rittenhouse Square, and weekends at a late-night karaoke and yakitori bar in Chinatown, all in an attempt to save up money for our band’s two-week tour in August. The tour was planned in support of our second album, which we’d just finished recording, despite the fact that no one had really cared much about the first.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

My new home was a far cry from the one I’d grown up in, where everything was kept spotless and in its place, our furniture and decor carefully curated to my mother’s specifications. Our living room had shelves made out of scrapped plywood and cinderblocks, which Ian, my drummer and roommate, had proudly salvaged from a trash heap. Our couch was a spare bench removed from the back of the fifteen-passenger van we used for touring.

My room was on the third floor. Across the hall was a small balcony that overlooked a baseball diamond where we could smoke cigarettes and watch Little League games in the summer. I enjoyed having a room on the top floor. The only real downside was that the ceiling in the closet was unfinished, exposing the beams and roofing, which never bothered me until a family of squirrels made its way through the roof and began copulating and nesting somewhere above. Sometimes at night, Peter and I would wake up to their scurrying and thudding around, which still wasn’t so bad until one of them fell into the hollow space between the walls and, unable to escape, slowly died of starvation. Its carcass released a thick, rancid stench into my room, which also wasn’t so horrible until in the unseen guts of the house, thousands of maggots spawned from the rot, breeding a plague of flies that confronted us one morning as I opened the bedroom door.

I had wound up doing exactly what my mother had warned me not to do. I was floundering in reality, living the life of an unsuccessful artist.

That March I turned 25, and by the second week of May I was starting to get antsy. I decided to head up to New York and meet with my friend Duncan, whom I’d known in college and who had since become an editor at The Fader. Privately, I was harboring a half hope that when the time came to finally give upon trying to be a musician, my interest in music might successfully parlay into a career in music journalism. As things stood, that time might be sooner than later. Deven, Little Big League’s bass player, had recently started playing in another band that was gaining traction. They were set to perform on the Lower East Side that very weekend at a small club exclusively for press, which in itself seemed a sure-enough sign that Deven would not be in our band for much longer. They were, in Deven’s words, on the path to becoming “Jimmy Fallon big.” I wasn’t quite ready to admit it, but I was going to New York that weekend, in part, to start laying the groundwork for something to fall back on.

The week before, my mother had mentioned she was having stomach problems. I knew she was scheduled to meet with a doctor that day, and I sent a few texts in the afternoon to follow up on her appointment. It was unlike her not to respond.

I boarded the Chinatown bus with a sinking feeling. My mother had mentioned a stomachache a couple months before that, in February, but I didn’t think much of it at the time. In fact, I’d made a joke out of it, asking in Korean if she had diarrhea: “Seolsaisseoyo?” It was a word I always remembered because it sounds a lot like salsa and, well, the similarity in texture made it easier to recall.

In my household, there was nothing to do for food poisoning except throw it up. Food poisoning was a rite of passage. You couldn’t expect to eat well without taking a few risks, and we suffered the consequences twice a year.

My mother rarely saw doctors, committed to the idea that ailments passed of their own accord. She felt Americans were overly cautious and overly medicated and had instilled this belief in me from a young age, so much so that when Peter got food poisoning from a bad can of tuna and his mother suggested I take him to urgent care, I actually had to stifle a laugh. In my household, there was nothing to do for food poisoning except throw it up. Food poisoning was a rite of passage. You couldn’t expect to eat well without taking a few risks, and we suffered the consequences twice a year.

For my mother to see a doctor, something had to be fairly serious, but I never considered it could be something lethal. Eunmi had died of colon cancer just two years before. It seemed impossible that my mother could get cancer too, like lightning striking twice. Nevertheless, I began to suspect my parents were keeping a secret from me.

The bus arrived in the early evening. Duncan suggested we meet at Cake Shop, a small bar on the Lower East Side that booked shows in the basement. I’d stuffed a hefty backpack full of clothes for the weekend and felt immediately frumpy and juvenile as I walked up Allen Street toward the bar.

Spring was giving way to summer and people getting off work were shedding their jackets, folding them over their forearms to carry. A familiar itch was creeping in. That aching toward something wild—when the days get longer and a walk through the city becomes entirely pleasant from morning to night, when you want to run drunk down an empty street in sneakers and fling all responsibility to the wayside. But for the first time it felt like an impulse I needed to turn away from. I knew there were no more summer vacations for me, no more idle days. I needed to accept that something, at some point soon, would have to change.

I got to the bar well before Duncan, who informed me he was running about twenty minutes late. I called my mom and got no answer. “What’s going on???” I texted, beginning to feel neglected. I dropped my bag beneath a bar stool and leafed through the records by the front window.

I’d never been especially close friends with Duncan. He was two years older than me and a senior at Haverford when we met. Buses ran between our two campuses and students from either school could enroll in classes and clubs at either college. Duncan was one of five members of FUCs, a group that was in charge of booking the bands that came to play on campus. He’d advocated for me when I applied to join, and now I hoped he might look out for me again.

I felt my phone buzz. It was my mother, finally, so I grabbed my bag and slipped outside to take the call.

“Mom, what’s going on?”

“Well, sweetie. We know you’re in New York for the weekend,” she said. “We wanted to wait until you were back in Philadelphia. When you’re at home and with Peter.”

Usually her voice trilled from the other end of the line, but now it sounded as if she spoke from a deadened room. I started to pace the block.

“If something’s wrong I’d rather know now,” I said. “It’s not fair to keep me in the dark.”

There was a long pause on the other end, one that indicated my mother had started the conversation with the intention of putting me off until I got home but was now beginning to reconsider.

“They found a tumor in my stomach,” she said finally, the word falling like an anvil. “They say it’s cancerous, but they don’t know how bad it is yet. They have to run some more tests.”

I stopped pacing, frozen and winded. Across the street a man was entering a barbershop. A group of friends sat at an outdoor table, laughing and ordering drinks. People were deciding on appetizers. Bumming cigarettes. Dropping off dry cleaning. Bagging dog droppings. Calling off engagements. The world moved on without pause on a pleasant, warm day in May while I stood silent and dumbfounded on the pavement and learned that my mother was now in grave danger of dying from an illness that had already killed someone I loved.

“Try not to worry too much,” she said. “We will figure this out. Go and see your friend.”

How? How how how? How does a woman in perfect health go to a doctor about an upset stomach and leave with a cancer diagnosis?

I could see Duncan turn the corner in the distance. He waved as I hung up. I swallowed the lump in my throat, slung my bag back over my shoulder, and smiled. I thought, Save your tears for when your mother dies.

Excerpted from CRYING IN H MART: A Memoir by Michelle Zauner. Copyright © 2021 by Michelle Zauner. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

If audio is more your thing, you can listen to the excerpt below, and read the rest of the book on Audible.

Audio excerpted courtesy of Penguin Random House Audio from Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner, read by the author

RELATED STORIES

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.

-

Tyla's Coachella Outfit Pairs Dolce & Gabbana With Pandora

Tyla's Coachella Outfit Pairs Dolce & Gabbana With PandoraThe singer wore a gold version of the crystal bra made famous by Aaliyah.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

How Kate Middleton Is Influencing George's Fashion Choices

How Kate Middleton Is Influencing George's Fashion ChoicesThe future king's smart blazer is straight out of Princess Kate's style playbook.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

King Charles "Couldn't" Meet Prince Harry During U.K. Visit

King Charles "Couldn't" Meet Prince Harry During U.K. Visit"It could actually bring down a court case."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

The 'Fourth Wing' TV Show: Everything We Know About the Series Adaptation

The 'Fourth Wing' TV Show: Everything We Know About the Series AdaptationRebecca Yarros's bestselling romantasy series is getting the Prime Video series treatment.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

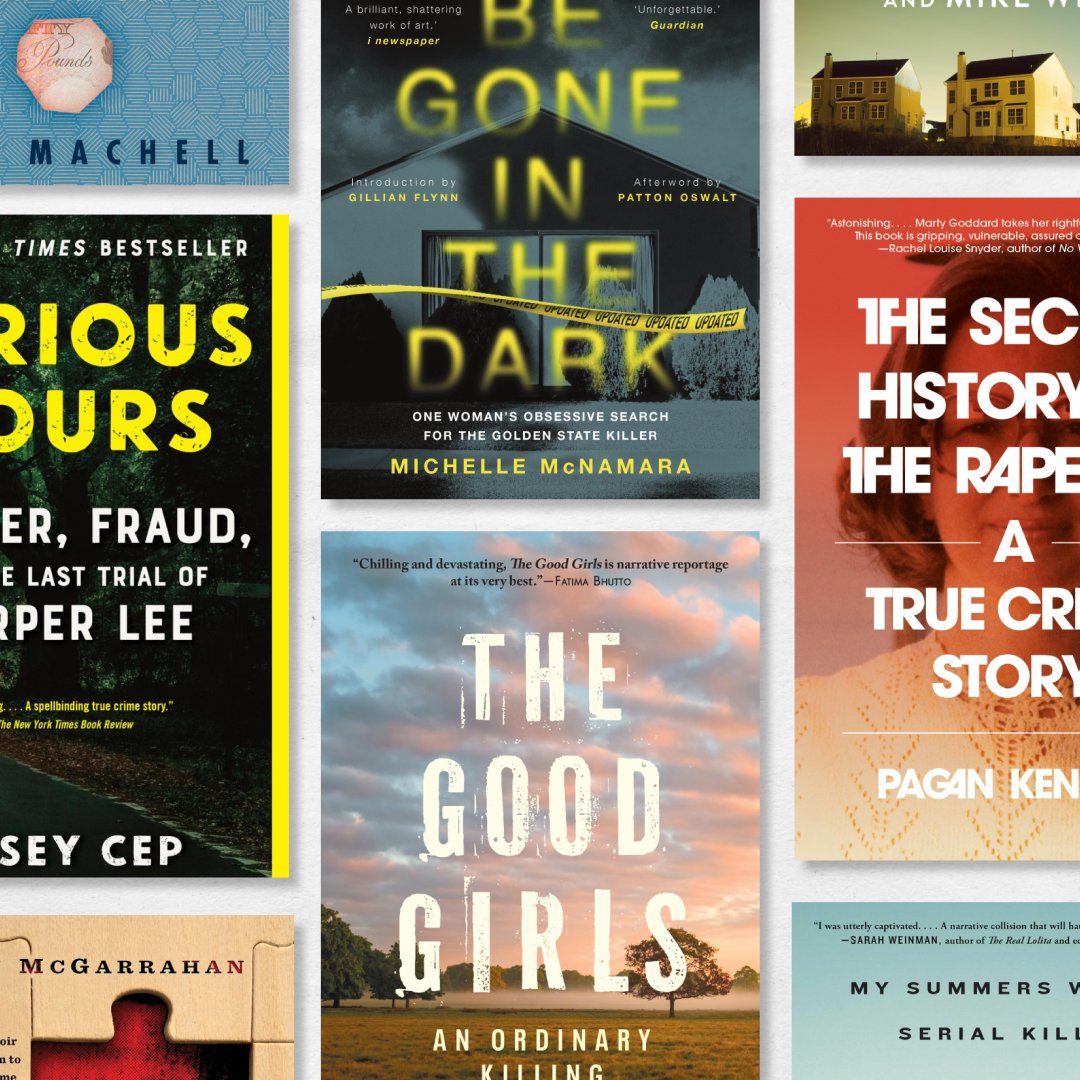

The 20 Best True Crime Books to Read in 2025

The 20 Best True Crime Books to Read in 2025These nonfiction titles and memoirs about serial killers and scammers are the definition of page-turners.

By Andrea Park Published

-

Every Ruth Ware Book, Ranked—From 'In a Dark, Dark Wood' to 'The Woman in Cabin 10'

Every Ruth Ware Book, Ranked—From 'In a Dark, Dark Wood' to 'The Woman in Cabin 10'Here's what you should read before her new thriller 'The Woman in Suite 11' hits shelves.

By Nicole Briese Published

-

10 Books to Read for a Killer Vacation

10 Books to Read for a Killer VacationPack these novels about vacations gone very wrong on your next trip.

By Liz Doupnik Published

-

The Melancholic Sound of Success

The Melancholic Sound of SuccessThe artist known as Japanese Breakfast opens up about finding her sound on a new album after experiencing whirlwind success.

By Sadie Bell Published

-

Every Jennifer Weiner Novel, Ranked—From 'Good in Bed' to 'In Her Shoes'

Every Jennifer Weiner Novel, Ranked—From 'Good in Bed' to 'In Her Shoes'All hail the queen of beach reads!

By Nicole Briese Last updated

-

The 28 Best Romantasy Books to Read in 2025

The 28 Best Romantasy Books to Read in 2025Here's what to read when you've devoured the 'ACOTAR' and 'Empyrean' series.

By Andrea Park Published

-

Mary Ellen Matthews Is the Woman Behind Every Portrait on 'Saturday Night Live' Since 1999

Mary Ellen Matthews Is the Woman Behind Every Portrait on 'Saturday Night Live' Since 1999The late-night show's resident photographer shares her favorite memories and insights from shooting all the talent who come through Studio 8H.

By Sadie Bell Published