Inside the Cutthroat World of Royal Gossips

They jet off to Fiji with Harry and Meghan, hike the Himalayas with William and Kate, and hit the South of France with Charles and Camilla. But the life of a royal correspondent isn’t all glamour; there’s fierce competition for scoops, backstabbing in the ranks, and chasing endless rumors about the privacy-obsessed monarchs. Now, with a protocol-defying American duchess and new baby prince, the profession has never been more intense.

Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, was going to give birth. As her rumored late-April due date inched closer, the British press was crazed trying to gain insight. Every day, new stories appeared: Meghan would copy her sister-in-law, Catherine, the Duchess of Cambridge, and opt for the fancy Lindo Wing, claimed one tabloid, referring to the private arm of St Mary’s Hospital in London where countless royal babies have been born (including Meghan’s husband, Prince Harry). No, swore another, she’s chosen a hospital in Surrey where Harry’s aunt gave birth. Actually, trumpeted a third, the baby will be born at Frogmore Cottage in Windsor, and it’s not only a home birth but a water birth. In reality, the only thing anyone knew for sure was that nobody knew anything, which, it seems, was just how Meghan and Harry wanted it.

For royal correspondents, whose livelihoods depend on reporting every intimate detail of the British royal family’s existence, the dearth of information was torturous, especially when compared with Kate’s three meticulously coordinated deliveries, during which the Cambridges’ communications team sent out regular updates. By contrast, the only detail Harry and Meghan were willing to confirm was that, unlike Kate and William, they wouldn’t hold a “photo call” (a British term for when press can take pictures and ask a few questions) on the day of the birth.

As April blossomed into May, reporters were getting impatient; some even had to cancel vacations when the baby had yet to arrive. To pacify them, the Sussexes’ press team, overseen by newly installed PR director Sara Latham, an American who had been a senior advisor for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, promised when the big day came, it would send an email confirming Meghan was in labor. And, to be fair, it did. Only, it sent an email saying she was in labor eight hours after their son, Archie, was born. Making matters worse, the email didn’t arrive in reporters’ inboxes until after 2 p.m., almost an hour after it was apparently sent. The delay was blamed on “technical difficulties,” but it didn’t go unnoticed that its arrival neatly coincided with morning talk shows in New York City, which is five hours behind the U.K. Meanwhile, British reporters scrambled to make deadlines, with one network failing to get the news into its lunchtime show.

Like everyone else, Rhiannon Mills, a royal correspondent for British network Sky News, didn’t get the palace’s email on time. She’d already been hanging around Windsor, a town an hour west of London where some of the royal family live, for a week waiting for Meghan to give birth. On the crucial day, Mills was at lunch with Max Foster, a rival reporter from CNN, when, around 1:40 p.m., her cell phone rang. It was Julie Burley, a member of the Sussexes’ press team. “Are you in Windsor?” Burley asked urgently. “Could you get a camera up to the castle?” Mills stiffened, suddenly alert. “Yes, that’s fine. Why?” she replied. “Because of the update I’ve just sent out,” Burley said.

Rhiannon Mills, a royal correspondent for Sky News (pictured here reporting on the birth of Prince William and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge’s second child, Charlotte, in 2015) broke the news earlier this year that Meghan was in labor.

Mills was puzzled. She hadn’t received an email. She asked Foster if he had. Nope, he said, no update. “I haven’t got this email, but what does it say?” Mills asked. “Oh, it says that the Duchess of Sussex went into labor this morning,” Burley said. As Foster would later tell her, Mills visibly paled. Swiftly making excuses, she ran out of the restaurant, leaving him to pick up the check. With one cell phone clamped to her ear and another at her fingertips, she texted her cameraman while calling the Sky News offices. “I was like, ‘Break it; she’s in labor,’” Mills recalls. Then, she logged on to Twitter—becoming the first person in the world to tweet that Baby Sussex was on his way.

With one cell phone clamped to her ear and another at her fingertips, Mills texted her cameraman while calling the Sky News offices. “I was like, “Break it; she’s in labor

Rhiannon Mills

When Mills arrived at Windsor Castle, there was bad news: The cameraman could go in—along with a photographer and reporter from the Press Association, a U.K. newswire—but Mills would have to wait outside. Just after 2 p.m., Prince Harry appeared. “I’m very excited to announce that Meghan and myself had a baby boy early this morning,” he said, grinning. On the other side of the gate, Mills was feeding live commentary to the Sky News studio while repeatedly refreshing her Twitter feed. But something was wrong. “No one else was tweeting about it,” she recalls. “And that does not happen with the royal pack.”

In fact, the rest of the royal press corps, which had only just received Burley’s email, was oblivious to the unfolding drama. Mills had scooped them all. Even the Press Association didn’t tweet about Meghan being in labor until 13 minutes after Mills. While she is coy about rivals’ reactions—“I will take my hat off and say that there have been moments when others have broken royal stories and you think, Oh, damn, I wish that was me,” Mills demurs—a source tells MC the royal press pack was furious.

Similar to the White House press corps, journalists on the royal beat are tasked with shadowing Britain’s princes and princesses at home and around the world. Mills has boarded a private jet in Fiji with Harry and Meghan, trekked Bhutan with William and Kate, and accompanied Prince Charles and his second wife, Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, on a Royal Air Force plane to the South of France. “It’s not a shabby job,” Mills says wryly. But while the role has touches of glamour, the reality is less enviable. Not only are the hours long and unpredictable, but correspondents must navigate a competitive media landscape as well as the privacy-obsessed royal family (nicknamed “the Firm” by the British press). And while much has been made of Meghan—American, biracial, and a former actress—shaking up the royals, the truth is, she has shaken up the British media too, with both journalists and palace staff struggling to adapt to what they see as her and Harry’s “micromanagerial” approach to their public image.

The first female royal correspondent was a statuesque reporter named Audrey Whiting, who worked for the Daily Mirror in the 1950s. Her colleagues joked she’d been given the job because she was six foot three and thus could peer over Buckingham Palace’s gates. But she also had a penchant for scoops: When she covered Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, she spotted Elizabeth’s younger sister, Princess Margaret, looking smitten with married Royal Air Force officer Peter Townsend. Whiting’s editor refused to print the story of a possible affair for fear of ruining the new queen’s “special day.”

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

In the six decades since Queen Elizabeth II ascended to the throne, the nature and pace of the media have mutated beyond recognition, but the inherent challenge of being a royal reporter has stayed the same: balancing the Firm’s desire for privacy with the public’s insatiable appetite for gossip. “The royal family are a public institution; we are paying for them” is how veteran freelance royal correspondent Phil Dampier justifies the scrutiny. Many of the privileges the royals enjoy, such as the chauffeur-driven cars, private jets, and fancy houses—even their own royal train, complete with a 12-seat dining table—are funded by U.K. taxes. According to the royal household’s annual financial report, published in June, the monarchy cost British taxpayers more than $84 million in the year spanning 2018 to 2019 alone, an increase of 41 percent over 2017 to 2018. In particular, Harry and Meghan’s decision to embark on a $3 million remodel of Frogmore Cottage has drawn criticism from those who think the money could have been better spent on public services. “People are paying for their lifestyle,” says Dampier. “So I think you have got a certain right to expect something back.” (The British economy also benefits from the royals, though: Business consultancy Brand Finance estimated the monarchy contributed about $2.2 billion to the U.K. economy in 2017.)

Of course, that doesn’t mean reporters are entitled to every facet of their lives. Katie Nicholl, a royal correspondent for Vanity Fair and Entertainment Tonight and author of Harry and Meghan: Life, Loss, and Love, says Harry once berated her when, in 2010, she wrote about then-girlfriend Chelsy Davy giving him a key to her apartment. “I’ll always remember Harry having a go at me and saying, ‘Why did you want to run that?’” Nicholl says. “It wasn’t a malicious story, but it upset him.” After the couple split, Nicholl learned the prince was dating someone new, but she decided not to reveal the budding romance lest she jeopardize it. “These are real people you’re writing about,” she says.

Which is why, in the same way Princess Margaret’s relationship with Townsend was, for a long time, ignored by the British press for fear of ruffling the royal family—despite American and European rivals gleefully covering it—rumors earlier this year of Prince William’s alleged affair with his wife’s friend Rose Hanbury, the Marchioness of Cholmondeley, have also been subject to an effective media blackout in the U.K. The scuttlebutt first flickered to life in March with a story in the British tabloid Daily Mail, which claimed a “rivalry” had emerged between Kate and Hanbury without explaining what may have caused it. A follow-up report in tabloid newspaper The Sun stating Kate wanted Rose “phased out” of the couple’s close-knit group of country friends, nicknamed the Turnip Toffs, gave the gossip oxygen. The Sun declined to offer any explanation for the presumed bad blood, leaving readers puzzled as to why the story caught fire. “It can feel as if you need a Ph.D. in cryptography to make sense of tabloid reports about the royals,” one gossip site snarked about the way the British media was tiptoeing around the rumors.

By contrast, outlets abroad seized on the story. In Touch splashed “William Cheats on Kate—With Her Friend!” on its cover in April. The French edition of Vanity Fair did a deep dive into the allegations, even suggesting that William’s supposed infidelity was the real cause of a falling-out between the Sussexes and Cambridges (not Meghan, who some publications implied was the source of tension). It even claimed Harry was reportedly furious at his elder brother for following in their father’s footsteps, since Charles’s affair with Camilla, decades earlier, had blighted the boys’ childhoods and set their mother, Diana, Princess of Wales, on a course to an early death.

Knowing royal secrets - even if they can’t be published - is one obvious perk of being a royal correspondent. Another is the opportunity to rub shoulders with the royals themselves

But you wouldn’t know any of this in Britain, where the closest anyone came to addressing the rumors publicly was when Hadley Freeman, a British-based American writer who works for The Guardian, tweeted: “I would really like someone to explain to me, a gauche clueless American, what the coded insinuation is in all the coverage of this story. Has there been an affair? Some other beheading-worthy offense? Just spell it out, for God’s sake.” Giles Coren, a columnist at The Times of London, replied: “Yes. It is an affair. I haven’t read the piece [Hadley was referring to] but I know about the affair. Everyone knows about the affair, darling.” Within hours, his tweet was deleted, although screenshots continued to circulate. (The Cambridges’ press secretary declined to comment on the rumors, but a source close to the couple strongly denies there is any truth to them.)

Knowing royal secrets—even if they can’t be published—is one obvious perk of being a royal correspondent. Another is the opportunity to rub shoulders with the royals themselves. “A lot of us have been doing the job for quite a long time, so when they turn up at [events], we are all familiar faces to them,” Mills says. “Prince Harry teased me for wearing high heels to get off the plane in Kruger National Park [a South African game reserve].”

Nicholl credits her entire career to a chance encounter with Harry 16 years ago. At the time, she was working at the British newspaper The Mail on Sunday, where she helmed the gossip pages. One evening, while sniffing out stories for her column at a celebrity-friendly nightclub next door to her office (which happens to be across the road from Kensington Palace), she stumbled across Harry in the flesh. The prince, then 18, was hosting a private event at the club, and when she stepped out for some fresh air, she spotted him smoking a cigarette. “He said, ‘Oh God, you look cold. Come in and join my party,’” Nicholl recalls. “I didn’t need inviting in twice. I spent the evening drinking vodka and Red Bull with the prince and his mates.” Although she didn’t spill any secrets from that night—“I felt that would be wrong and burn bridges,” she explains—the experience sparked a fascination with Harry and his family, and Nicholl was soon promoted to the royal beat.

But while the private jets, exotic locations, and five-star hotels are invariably fun, the job can also be grueling. “It can be hard sometimes when you’re [waiting] in a cold, wet car park,” Mills admits as she sinks into an oversize armchair at Sky News’s West London campus, a teacup balanced precariously on her lap. She once spent three hours outside the Taj Mahal in 113 degree heat waiting for William and Kate to turn up. The discomfort is amplified by the personal sacrifices many reporters make. Every Christmas, for example, many reporters abandon their families to watch the royals arrive for services at a 16th-century church in Norfolk, where temperatures sometimes plunge to 27 degrees. And in May, as the world awaited Archie’s arrival, the Daily Mail’s longtime royal correspondent Rebecca English tweeted: “My son just said he was ‘going to say a prayer to God that Meghan doesn’t have her baby today so you can come to my guitar recital as I’m so nervous and it won’t be the same if Mummy isn’t there,’” with a tearful emoji.

The view from the press pack of Prince Harry and Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, leaving the Sydney Opera House, which they visited as part of a 16-day tour to Australia, Fiji, Tonga, and New Zealand, October 2018.

All of which makes the misconception that royal reporting isn’t “real” news sting. It’s an aspersion that can limit careers. “I was a little bit apprehensive about taking the job because you think that it might end up pigeonholing you,” Mills reveals. “You might end up becoming the ‘nice frocks and corgis’ correspondent.” That’s despite Mills having paid her dues as a general news reporter for over a decade and the fact that reporting on the royals often requires expertise in politics and foreign affairs. When President Donald Trump arrived in Britain for a state visit in June, Mills was front and center, analyzing the significance of his interactions with Queen Elizabeth and her relations. She was even sent on a training course to learn how to navigate war zones since the royals often travel to Africa and the Middle East; the other journalists on the program couldn’t hide their amusement when Mills revealed her beat. “The biggest laugh I got was when I did the Hostile Environment course,” she admits.

The most challenging aspect of the job, however, is navigating the royals’ “no comment” culture, in which royal press secretaries refuse to confirm or deny any reports in the hope that readers will disbelieve them all. To say the British royal family—and in particular William and Harry—has a complicated relationship with the press would be an understatement. As children, the brothers endured having every excruciating detail of their parents’ acrimonious divorce splashed across tabloid front pages, including the contents of a private telephone call in which Charles told Camilla, then still his mistress, that he wanted to be reincarnated as a tampon so he could live inside her pants. Four years later, their mother, Diana, was killed in a car crash while trying to outrun a swarm of paparazzi in Paris, some of whom continued to photograph her as she lay dying.

No wonder William, in a 2017 documentary that aired on HBO to commemorate the 20th anniversary of his mother’s death, said solemnly, “You’ve got to maintain a barrier and a boundary [with the media] because if you cross it—if both sides cross it—a lot of pain and problems can come from it.” Charles has been even more vocal in his hostility toward reporters. During a photo call in 2005, microphones inadvertently recorded him muttering, “Bloody people” and, referring to the BBC’s veteran royal correspondent Nicholas Witchell, adding, “I can’t bear that man. He’s so awful; he really is.” Even the youngest royals seem to have inherited their family’s antipathy. Last July, when Prince George, 6, and Princess Charlotte, 4, attended younger brother Prince Louis’s christening alongside their parents, Kate and William, Charlotte famously turned to the reporters waiting outside the chapel and announced, “You’re not coming.”

Photographers clamour to get a shot as Prince William and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, leave St Mary’s Hospital with their son Louis in 2018.

On rare occasions, the royals will even go so far as to sue. In 2017, William and Kate were awarded $120,000 by a court after the French magazine Closer published topless photographs of Kate sunbathing on a private estate in 2012. The long-lens paparazzi shots were first offered to several British publications, which declined to print them. “That would have been suicidal,” says Duncan Larcombe, who spent over a decade as a royal correspondent at The Sun. And earlier this year, Harry and Meghan took court action against British news agency Splash, which used a helicopter to snap aerial photographs of an Oxfordshire country house the couple was renting while they waited to move into Frogmore. The pictures, published in a handful of British newspapers, showed the interior of the living and dining areas and the bedroom, which “seriously undermined” the couple’s security, according to their lawyer, causing them to move out. (In May, the Sussexes accepted a settlement and an apology.)

Some royal watchers see the Splash lawsuit as a warning, especially since it followed a slew of negative headlines about Meghan that emerged toward the end of 2018. Such stories labeled her “Duchess Difficult” and said that before her wedding to Harry, she reportedly threw a tantrum over a tiara. Meghan couldn’t address the rumors directly, so in a bid to defend her, five of the duchess’s friends spoke anonymously to People magazine. Titled “The Truth About Meghan,” the six-page spread, published in February, highlighted the duchess’s generosity, empathy, and kindness. “We want to stand up against the global bullying we are seeing,” they told the magazine. It was widely thought that Meghan sanctioned, if not outright orchestrated, the story, and the fact that it was published in a celebrity-friendly American magazine was interpreted as a message: The British press is full of bullies.

Some of the most salacious tittle-tattle originates from inside the palace. “It was often said [servants] would leak stories simply because their pay was so bad,” says Dampier.

But some of the most salacious tittle-tattle originates from inside the palace. “It was often said [servants] would leak stories simply because their pay was so bad,” says veteran royal correspondent Dampier. Some former staff even published books about their experiences in the royal household, including Queen Elizabeth’s personal chef, Darren McGrady, and her childhood nanny, Marion Crawford, who was ex-communicated by the Firm for the rest of her life for the perceived betrayal. Diana’s former employees also released memoirs after her death, including bodyguard Ken Wharfe and butler Paul Burrell, who wrote no less than two books in which he detailed the princess’s former lovers and included excerpts from her private letters.

Reporters also have sources in the royals’ high-society circle. The infamous photo of Harry dressed in a Nazi uniform at a costume party in 2005, for example, came courtesy of a fellow guest. Occasionally, the royals’ own staffs will intentionally feed the press news. In 1999, when Charles’s approval ratings were at their lowest and he was desperate to marry former mistress Camilla Parker Bowles, his press secretary leaked stories about the couple’s relationship to test the reaction. It was a smart move; through these reports, the public came to accept Camilla, who Charles married in 2005. Other times, the royals themselves plant fake stories among their friends to weed out those who talk to the press. “I’ve spoken to William about it, and I do know that used to be something that they did,” reveals Larcombe, but he says he never discovered which stories were fabricated.

In the 1980s there were roughly five royal correspondents, most of them from British tabloids, but today there are at least 24 U.K.-based reporters on the royal beat and dozens more who hail from countries worldwide. Many of them work entirely online, where they can easily scoop their print counterparts. When it comes to royal reporting, “it’s every man for himself,” says Larcombe.

In the 1960s and ’70s, when reporters still filed stories via public telephones, it wasn’t unheard of for royal correspondents to vandalize the handset after filing their copy in order to sabotage the next reporter’s deadline. And when, in the early 1990s, two royal reporters discovered Charles and Diana had changed their vacation plans from Spain to Italy, they didn’t warn the rest of the press pack, letting them fly to Mallorca. “They were in the wrong place with nobody, in the wrong country, everything,” recalls one former royal correspondent who asked to remain anonymous. “That kind of thing can lead to people losing their jobs, and in that case, I think it did.” More terrifying than missing a scoop is getting one wrong. “The worst thing that can happen to a newspaper or, heaven forbid, a royal correspondent is for them to become the story,” Larcombe says. In 2008, a young royal correspondent for the Evening Standard wrote that Prince Philip, the queen’s husband, was battling prostate cancer. The palace issued a rare denial, and the newspaper published a retraction, which became the focus of the story. “Even if you get things right, people at the palace sometimes lie,” says Dampier, citing the last weeks of Charles and Diana’s marriage. During their final joint royal tour, to South Korea in November 1992, whispers about the couple’s imminent separation reached a crescendo, but their press secretary denied any issues. The split was formally announced the next month. “A lot of stuff comes out at a later date,” Dampier explains. “Sometimes with royal reporting, you’re months, if not years, behind the game.”

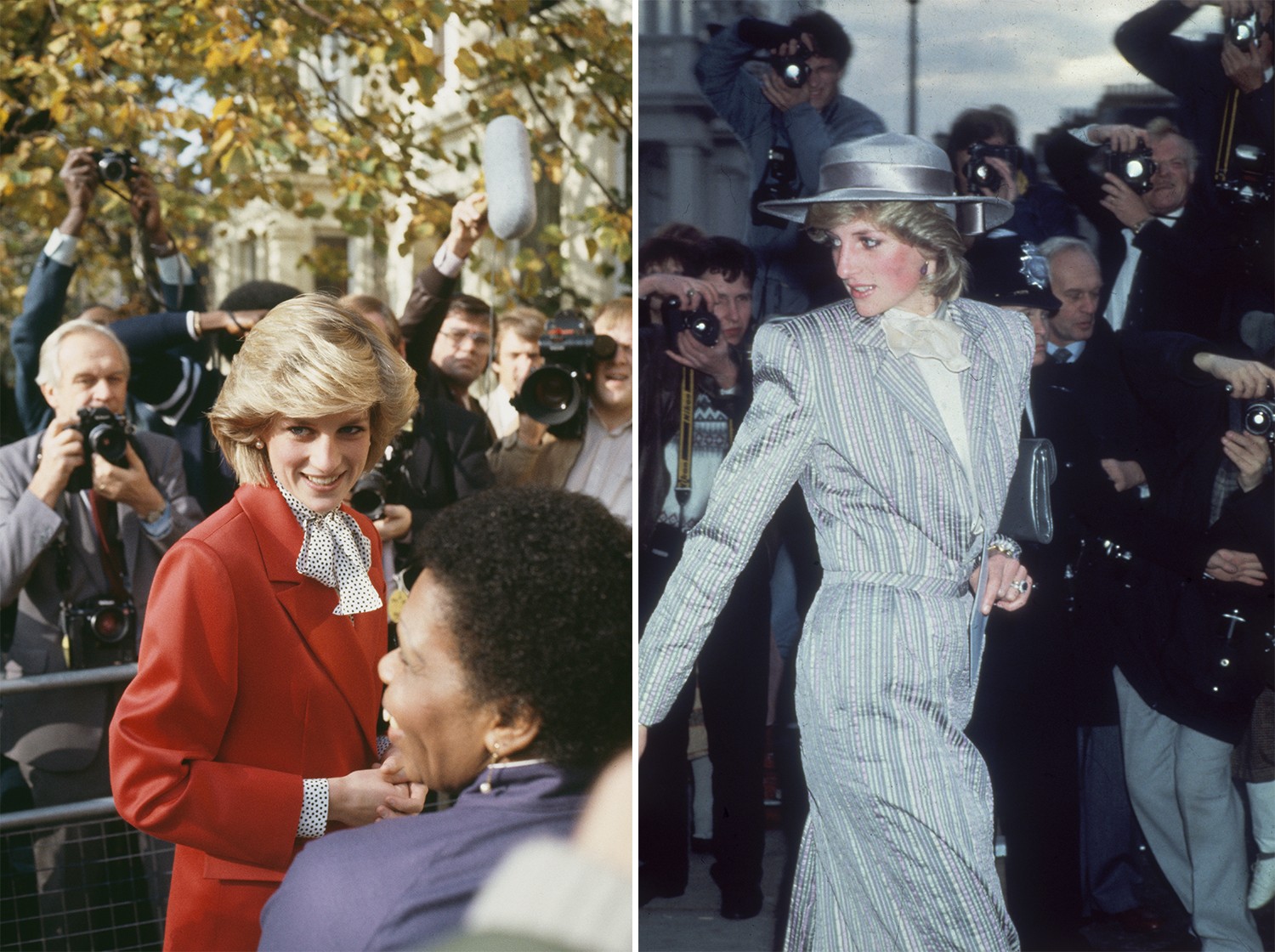

The royal press frenzy rose to a new level when Diana, Princess of Wales (seen here visiting Brixton Community Centre in London, 1983 (left) and at her friend Anne Bolton’s wedding, 1983) arrived on the scene.

Social media has only contributed to the pressure faced by royal correspondents. The increasing popularity of the Firm, particularly in America, has spawned armies of trolls who besiege any reporter who dares write anything less than glowing about the favorite royals. Every afternoon in London, as morning dawns on the East Coast, a barrage of online abuse begins anew, one editor complains. “Anything that you write about Harry and Meghan that is seen to be at all critical unleashes a load of Twitter trolls,” agrees Dampier. “It can become quite nasty.”

The arrival of an American actress in the family has shaken up not just the British press but the royals themselves. “They’re the royal rock stars at the moment,” Mills says of Harry and Meghan. There have even been rumors of jealousy between the Cornwalls (as Charles and Camilla, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall, are known), the Cambridges, and the Sussexes, especially since Charles and William, as direct heirs to the throne, outrank Harry. Rumors of a rift were furthered by an announcement in March that Harry and Meghan were setting up their own court (after years of sharing staff with William and Kate), followed by the rupture in June of the Royal Foundation, a charity the quartet oversaw, with Harry and Meghan departing the organization with plans to form their own.

The splitting of the “Fab Four,” as the two couples had been nicknamed, has sparked a frenzy among members of the press, who have likened the breakup to a modern-day War of the Roses (a series of clashes between rival branches of royals who fought over the throne in the 1400s), especially online. In May, the Cambridges’ Instagram account posted photos and videos of Kate and William’s children at the Chelsea Flower Show, including one in which the youngest, Prince Louis, is seen toddling for the first time. On the same day, the Sussexes published a video montage in honor of their first wedding anniversary. Reporters gleefully compared the number of “likes” each post garnered, with House Sussex (1.7 million) coming in above House Cambridge (1.1 million). In June, when @sussexroyal posted a birthday message to William, articles analyzed whether it was affectionate enough. Similarly, when Harry and Meghan wished Prince George a happy birthday the following month, critics scolded the couple for not using the 6-year-old’s proper name and title.

Prince Harry and Prince William greet reporters on the eve of Harry's wedding in 2018.

Such tensions, real or imagined, are a boon for reporters. But international interest in the Firm means the stakes are higher too. Because royal stories reverberate globally, often converging with other beats—gossip, entertainment, politics—royal reporters must compete with an increasing number of journalists. It’s rumored the freelance royal scribe who uncovered Harry and Meghan’s relationship in 2016 so disliked one tabloid reporter that he sold the story to her rival. (He denies that was the reason.)

The increased interest from abroad has also fueled transatlantic media animosity that began during Harry and Meghan’s 2018 wedding, when the royal press corps found itself overshadowed by American behemoths with bigger budgets that muscled in on the best vantage points around Windsor Castle. Warner Brothers spent $125,000 hiring out the Horse & Groom pub opposite the castle gates. Meanwhile NBC built a studio on the roof of the MacDonald Windsor Hotel, across from the castle (requiring the building’s top floor to be reinforced); rented another venue, the nearby Carpenters Arms pub, reportedly at a cost of $37,000; and even sent letters to residents of King’s Road, located on the wedding-carriage-procession route, offering five-figure sums to take over their homes and gardens. “It was quite incredible seeing the American networks that came over and literally demolished top floors of hotels to build studios,” marvels Sarah Campbell, one of the BBC’s four royal correspondents.

The rivalry intensified during Meghan’s pregnancy, with what British reporters saw as her favorable treatment of the U.S. press. While American media titans have flaunted friendships with the Los Angeles–born duchess, the royal press pack hasn’t even been formally introduced to her, despite spending two weeks trailing the couple on their first royal tour last fall.

If there was mounting frustration on the part of the British press during the pregnancy, it reached a fever pitch following the royal birth. After the Sussexes were back home at Frogmore Cottage, their press secretary would not confirm whether Archie had been delivered at home or in a hospital. (The Daily Mail scooped everyone the next morning by revealing the duchess had given birth at the Portland, a private, American-owned hospital in London.) But the Sussexes never confirmed the report, despite knowing it would be corroborated by their son’s birth certificate, a public document that would be released weeks later.

Archie’s official Christening photograph, released by Harry and Meghan in July. The private ceremony exemplified how the Duke and Duchess are changing the way they interact with the media, often bypassing the press altogether.

The next day engendered yet more resentment against the American press when it was revealed that, at the last minute, Harry and Meghan had accredited a CBS cameraman for Archie’s public debut. Considering that only a single photographer, reporter, and video journalist from the whole British press corps had received accreditation, there was tension when they were told CBS would join them. “It’s quite provocative the way that they got CBS in on that photo call,” the anonymous ex–royal correspondent says testily. “The Americans don’t pay for the royal family, so why should they get special access?”

The first week of Archie’s life brought more acts the royal press corps found difficult to stomach. Meghan and Harry broke with decades of royal tradition by omitting the signatures of the doctors who delivered Archie from the official notice posted at Buckingham Palace. Then the couple decided not to share Archie’s name during the photo call. Instead, they announced it on Instagram, bypassing the press altogether. “They’re able to control their media by putting it all out there on their own,” Campbell says. And their decision, a week later, to Instagram a picture of Archie’s feet in honor of Mother’s Day in the U.S. was deemed a final insult by some reporters.

With the young, modern couple following the trend of celebrities everywhere—who increasingly eschew traditional media in favor of telling their stories themselves on social media—royal correspondents are learning to adjust. “It means that you have to be more agile and constantly refresh your social media,” says Mills. The couple’s decision to appoint a “social media expert,” as the Daily Mail reported in June, is emblematic of this strategy. “This is a couple who is trying to reclaim the narrative when it comes to how they want to be portrayed in the media,” Nicholl says. “We’re not going to get the heads up that we are used to getting with other members of the royal family. I think there’s a feeling that it’s going to be a lot more spontaneous with the Sussexes and on their terms rather than what suits us, the media.”

Despite such challenges, most royal reporters love the job, especially the opportunity to watch history unfold. “Not everyone likes the royal family,” Campbell says. “But it does feel like, when you turn on the news and Brexit has been so divisive, a royal birth or wedding can bring the country together in a way few other stories can.”

That was evident in May, about a week after Archie’s birth, when Prince Harry visited a children’s hospital in Oxford. The weather, for once, was favorable, and Mills, who arrived two hours early, surveyed the throngs gathering outside the hospital from behind her sunglasses. Spotting a chubby blond baby in the crowd, Mills predicted Harry would stop to coo at the infant and staked out a vantage point.

Daisy Wingrove, a 13-year-old former cancer patient, gifts Prince Harry a teddy bear for Archie in May at the Oxford Children’s Hospital.

Eventually, flanked by a police escort, the prince’s Jaguar glided in to cheers. On behalf of the hospital, 13-year-old former cancer patient Daisy Wingrove gave the prince a teddy bear for Archie, and as she handed it over, an “awww” emanated from the crowd. “Awww,” Harry repeated with a grin, cracking up the onlookers.

After hugging Daisy, he spoke to nurses, shook hands, and, as Mills predicted, stopped to coo at the baby. “You see, he’s gone completely rogue,” Mills whispered. Everyone Harry spoke to was left beaming; one nurse wiped a tear. Finally, officials ushered the prince into the building, where he spent the next hour meeting ill children. Then, amid a whir of paparazzi shutters, he was back, stopping for a few selfies before speeding off to a nearby sports center for the disabled, ready to sprinkle more royal stardust. Most media had already melted away; only an American producer from NBC was still hanging around as Mills kicked off her pumps, shoved them into her purse, and slipped on a pair of sparkly silver sneakers, ready to sprint back to her car so she could follow Prince Harry to his next destination.

Illustrations by Susanna Hayward. Lead Animation by Colin Gara.

This story originally appeared in the 2019 September issue of Marie Claire.

Related stories

Just 62 Photos of Prince Harry With Kids

-

Sarah Jessica Parker Test-Drives the New Platform Ugg

Sarah Jessica Parker Test-Drives the New Platform UggCarrie Bradshaw would have some thoughts on the exceedingly fluffy footwear.

By Amy Mackelden

-

Michelle Obama Elevates Baggy Cargo Pants With a $3,700 Tote

Michelle Obama Elevates Baggy Cargo Pants With a $3,700 ToteThe former First Lady elevated her casual outfit with sleek accessories.

By Amy Mackelden

-

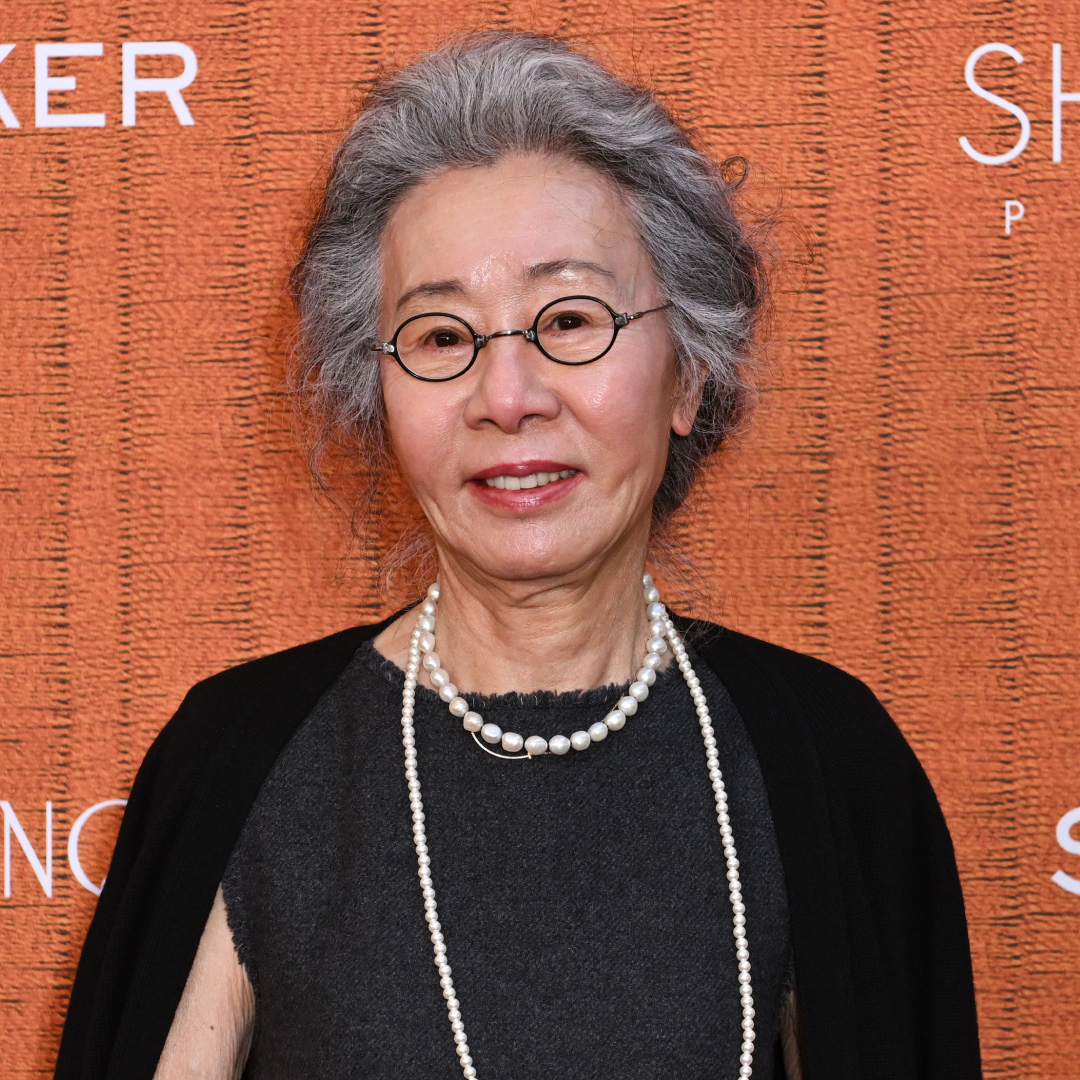

Youn Yuh-Jung Didn't Want to Make Another American Movie—Then Came 'The Wedding Banquet'

Youn Yuh-Jung Didn't Want to Make Another American Movie—Then Came 'The Wedding Banquet'The Oscar winner shares why the LGBTQ+ rom-com hit close to home and the message she hopes it sends to ''conservative'' Koreans.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Prince Harry Requested "Certain Protection" After Receiving a Shocking Threat Against His Life

Prince Harry Requested "Certain Protection" After Receiving a Shocking Threat Against His LifeBritain's Home Office released new details about a terrorist threat that targeted the Duke of Sussex.

By Kristin Contino

-

Princess Kate Is Channeling Princess Anne's Signature Style in an Unexpected Way

Princess Kate Is Channeling Princess Anne's Signature Style in an Unexpected WayThe Princess of Wales is following in the no-nonsense Princess Royal's footsteps.

By Kristin Contino

-

Princess Kate Is Trading Her Easter Sunday Hat for Skinny Jeans After Skipping Royal Easter Celebration

Princess Kate Is Trading Her Easter Sunday Hat for Skinny Jeans After Skipping Royal Easter CelebrationHere's what the Wales family is doing instead.

By Kristin Contino

-

Princess Diana's Close Friend Reveals What She Likely Would Have Thought About Meghan Markle

Princess Diana's Close Friend Reveals What She Likely Would Have Thought About Meghan MarkleRichard Kay shared insights on the late royal and what her relationship with Prince Harry's wife could've been like.

By Kristin Contino

-

Prince William and Princess Kate Could Take Legal Action Over These Spring Break Photos

Prince William and Princess Kate Could Take Legal Action Over These Spring Break PhotosPaparazzi snapped pictures of the family during their secret French getaway.

By Kristin Contino

-

This Royal Couple Has the Most Pinned Celebrity Wedding of All Time—And a Surprising Royal Wedding Didn't Even Make The List

This Royal Couple Has the Most Pinned Celebrity Wedding of All Time—And a Surprising Royal Wedding Didn't Even Make The ListA new study found this ceremony gave Pinterest users the most inspiration.

By Kristin Contino

-

Royal Sources Give Update on "Distant" Relationship With Prince Harry and King Charles

Royal Sources Give Update on "Distant" Relationship With Prince Harry and King CharlesInsiders close to the Duke of Sussex have revealed whether there is a chance at reconciliation in the near future.

By Kristin Contino

-

Princess Kate Opens Up About "Spiritual" and "Very Intense" Feelings in Surprise New Video

Princess Kate Opens Up About "Spiritual" and "Very Intense" Feelings in Surprise New VideoThe Princess of Wales shared one thing that has helped her find "peace and reconnection" amid her health battle.

By Kristin Contino