My Terrifying Week Being Smuggled Out of Syria

Crammed onto a boat with 500 other refugees, watching it sink, realizing the red water it slipped into was filled with the blood of her fellow passengers—these are just some of the horrors Doaa Al Zamel had to endure in order to escape Syria's brutal civl war. In this exclusive excerpt, author Melissa Fleming chronicles a miraculous—but all too common—journey.

Doaa Al Zamel grew up in Daraa, Syria, now known as the "cradle of the Syrian revolution." When Doaa was a 16-year-old high school student in 2011, President Bashar al-Assad's tanks and troops invaded the city, reducing it to rubble and killing thousands of civilians, forcing many of those who remained to flee. A year later, the Al Zamels sought safety in Egypt, where Doaa met fellow Syrian refugee Bassem, 28. The two fell in love and got engaged, and when the tide started turning against Syrian refugees in Egypt, they decided to try to reach Europe to start a new life in Sweden.

It was 11 a.m. on September 6, 2014, when the call came. Doaa carefully repacked a change of clothes for herself and her fiancé, along with their toothbrushes, a large plastic bag of dates, and a big bottle of water, and placed them one by one into the Mickey Mouse backpack she'd kept from her school days back in Syria. She wrapped their passports and engagement contract in plastic wrap, then dropped them in a sandwich bag and folded over the end. Next, she placed her mobile phone and wallet with 500 euros and 200 Egyptian pounds in a separate plastic bag—and secured each bundle underneath the straps of her red tank top, the first of four layers of clothes she had carefully selected for the journey. The plastic immediately made her skin sweat in the humid late-morning heat.

Five minibuses packed with fellow Syrian and Palestinian refugees were waiting outside the apartment complex. Doaa and Bassem climbed inside and found a single seat to share, wedging their bag and two life jackets between them and the window. People were packed in so tightly that Doaa could barely breathe, and there was a hushed tension as the bus joined a convoy moving in the direction of the highway. Just when she felt like she was about to faint from the stifling air, they veered off into a truck stop and pulled alongside a big, run-down bus. They were ordered to get off and join other passengers in the bigger bus. People on this second bus were already sitting on each other's laps or standing crammed together. "Get in, dogs!" was the first order they heard. Another smuggler rasped, "If anyone opens his mouth, we'll throw you out the window!"

"I feel like we are being taken to our deaths," Doaa told Bassem. Just days before, she had also said to him that, as much as she tried, she couldn't picture them in Italy or Sweden or anywhere in Europe. "The boat is going to sink," she told Bassem flatly. He had brushed off her remark, joking that her lifelong fear of the water and inability to swim were getting the best of her.

Mourners in Gaza City throw roses into the water in memory of Gazans who died at sea, 2014.

At 11 p.m., they came to a halt about half a kilometer from a barren, sandy beach. "Get out and run to the shore!" the smugglers shouted. They filed out and noticed other buses, and hundreds of people ahead of and behind them. Bassem kicked off his flip-flops and took Doaa's hand; they sprinted toward the water. As they reached the shore, Doaa pleaded with him to wait before stepping into the swell. "I need to gain my courage," she said. "Trust in God's will, Doaa, and be brave; this is our only chance," he replied, gripping her hand as he charged into the water. Doaa felt the waves swallow her calves, then her knees, and soon they were up to her waist.

One of two wooden dinghies, about three and a half meters long, was moving toward them, but to reach it, they had to struggle through breaking waves until the water was up to Bassem's shoulders. It would have been over Doaa's head, but her thin life jacket, along with her tight grip on Bassem, just barely kept her afloat. The vest rose to the surface and circled her face, keeping her chin at water level. She realized then that the shop that sold the vests for $50 each had scammed them; these were fakes. A new industry had sprung up, exploiting refugees by producing and selling substandard life jackets. Some of the vests' fillings were made of cheap, absorbent material. Or, in Doaa's case it seemed, thin sheets of foam that provided only the slightest buoyancy. They reached the dinghy, and Bassem pulled himself over the side while a smuggler lifted Doaa in.

When the dinghy neared the larger boat that was to take them across the sea, Doaa felt a chill of panic. She and Bassem had never quite believed the vessel that would take them to Europe would look like the cruise liners advertised on some of the smugglers' Facebook pages, or the "four-star ship" their smuggler described to them over the phone. But this fishing trawler—not a passenger ship—in decrepit state was far below their expectations. Its blue paint was peeling, and its rims had turned to rust.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Hundreds of people were already on the boat when Doaa and Bassem climbed on deck. They soon learned that a good number of these weary-looking travelers had been drifting at sea for days, impatiently waiting for Doaa and Bassem's group to join them so the smugglers could fill every square inch of the trawler. The more people the smugglers could pack in, the more profit they would make. Bassem estimated that there were at least 500 refugees on board when the boat set off. If every passenger paid $2,500 each, as Bassem and Doaa had, the smugglers would be collecting over $1 million. More, if they also charged for the 100 children on board.

She realized then that the shop that sold the vests for $50 each had scammed them; these were fakes. A new industry had sprung up, exploiting refugees by producing and selling substandard life jackets.

It was late afternoon on their third day when a double-decker boat approached. One of the smugglers explained that the waves were too high for so many people and they had to split up. About 150 others disembarked with Doaa and Bassem, all joining several hundred passengers on the other boat. They'd been told the trip would take two days at most; nearly four had passed. "How much longer?" someone asked the new captain. "Just 19 hours, and we will reach Italy," he reassured them. They cheered and clapped, calling out, "Inshallah, God willing, we will make it to Italy!"

But just hours later, Doaa was napping when the sounds of an engine and men shouting insults in an Egyptian dialect startled her awake. A blue fishing boat approached them at full speed. Doaa could see about 10 men on board, dressed in ordinary clothes, not the all-black outfits of the smugglers. Doaa had never seen pirates before, but the malevolence she saw in the men's faces brought the word to her mind.

"You dogs!" they shouted. "Sons of bitches! Stop the boat! Where do you think you are going? You should've stayed to die in your own country!" One of the smugglers on Doaa's boat shouted at the men: "What the hell are you doing?!" "Sending these filthy dogs to the bottom of the sea!" one of them yelled in reply. Then, all of a sudden, they began hurling planks of wood at the passengers on the refugee boat, their eyes wild with hatred. Doaa stared in horror as the boat sped toward them.

"Doaa, Doaa, put on your life vest!" Bassem's voice screamed, shaking her from her paralysis. "They are going to kill us!" All around them, passengers panicked. There was a scramble for life jackets, as desperate prayers were interrupted by terrified shouts and children crying. The boat approaching them accelerated and rammed into the side of their boat just below where Doaa and Bassem were standing, producing a shriek of metal and shattering wood. The impact was so sharp and sudden, it felt like a missile strike. Doaa stumbled forward, almost falling over the railing before Bassem's arms shot out and grabbed her. Other people weren't so lucky and fell over, landing on the hard deck and other passengers below. In the commotion, Doaa had dropped her life vest. She was frantically looking for it when Bassem pulled her toward him. She then realized that their boat was beginning to turn on its side. Oh, God, Doaa thought. Not the water. Not drowning. Let me die now and not go into the sea.

Doaa could hear the men on the attacking boat laughing as they hurled more pieces of wood. Those laughs were one of the most horrifying sounds she had ever heard. She couldn't believe they were enjoying themselves during their act of cruelty or that anyone would sink a boat carrying children.

The attackers sped toward them again, and when they rammed the side of Bassem and Doaa's boat, the rickety vessel took a sudden, violent nose-dive into the sea. Bassem's hand was yanked away from Doaa's as he fought to regain his balance, and she lost sight of him in the mass of people tumbling forward. As people began to fall into the water, the men on the attacking boat jeered, calling out that each and every one of them should drown. "Let the fish eat your flesh!" they yelled as they sped away.

Sisters Sandra, 6, and Masa, 18 months, in a photo taken in Egypt just before boarding the boat bound for Italy, 2014

Half of their boat was already underwater; it was sinking fast. Doaa thought of the hundreds of people trapped in the hull. They're doomed, she thought as she held on to the edge of the sinking vessel, and so are we.

She heard screaming all around her, muffled only by the sound of the boat's motor. People desperately grabbed on to anything that floated—luggage, water canisters, even other people, pulling them down with them. Doaa noticed that the sea around her was red and soon realized that people were being sucked into the boat's propeller and dismembered by its blades.

Overwhelmed with panic and fear, Doaa began shouting for Bassem. A few long seconds later, she heard his voice. She turned her head toward the sound and spotted him in the sea. She wanted to go to him but couldn't bring herself to jump into the water. The boat was sinking at an angle that was drawing her toward the spinning propeller. "Let go, or it will cut you up, too!" Bassem cried out.

She closed her eyes and opened her hands, falling backward, arms and legs spread as she hit the water. She was buoyant for a few seconds on her back, then she felt someone pulling at her headscarf, which slipped off her head. As she lay floating on her back, she felt her long hair being yanked under the water. Those who were drowning below were grabbing at whatever they could to try to pull themselves to the surface. They pulled Doaa's face below the water, but somehow she managed to push their hands away.

Then she spotted Bassem swimming toward her holding a blue floating ring, the kind toddlers use in baby pools. "Put this over your head so you can float," he said as he passed her the partially inflated ring.

Of the 500 people who had been on board, somewhere between 50 and 100 survived the attack and were left floating aimlessly in the sea. As the night wore on, more people would die from cold, exhaustion, and despair. Some who had lost their families gave up, taking off their life jackets and allowing themselves to sink into the sea.

Solidarity emerged among those who were left. People with life jackets moved closer to those without them, offering a shoulder to hold on to for a rest. Those with food or water shared it. Men and women whose spirits remained strong comforted and encouraged many who wanted to give up.

When the sun rose the next day, it was clear to Doaa that the night had taken at least half of the initial survivors. A small group of those remaining gathered around Bassem and Doaa, treading water. Some were speaking in a state of delirium. Amid the cacophony, Bassem looked directly at Doaa and, loud enough so that everyone could hear, said, "I love you more than anyone I have ever known. I'm sorry I let you down. I only wanted what was best for you." He spoke with urgency—it was as though getting the words out was the most important thing he'd ever done. "It was my job to take care of you, and I failed. I wanted us to have a new life together. I wanted the best for you. Forgive me before I die, my love."

"There's nothing to forgive," Doaa told him. "We will be together always, in life and in death." She pleaded with him to hold on, telling him over and over that he was not to blame. As she reached to stroke his cheek, she noticed an older man swimming toward them, clutching a baby on his shoulder. When he reached them, he looked at Doaa with pleading eyes and said, "I'm exhausted. Could you please hold on to Malak for a while?" The baby was wearing pink pajamas, had two small teeth, and was crying. Doaa thought she looked just like what the name Malak meant—angel. The man explained that he was her grandfather. There were 27 members of their family on that boat, and the rest had all drowned. "We are the only two who survived. Please keep this girl with you," he begged. "She is only 9 months old. Look after her. Consider her part of you. My life is over."

They're doomed," she thought as she held on to the edge of the sinking vessel, and "so are we.

Doaa reached for Malak and settled the baby on her chest, resting the girl's tiny cheek next to her heart. At Doaa's touch, Malak relaxed and stopped crying, and Doaa immediately took comfort in having the child's body next to hers. Malak's grandfather touched Malak's face and said, "My little angel, what did you do to deserve this? Poor thing. Good-bye, little one; forgive me; I am going to die." He then swam off. The next time they looked in the old man's direction, they saw him floating facedown in the sea.

"I'm scared, Bassem," Doaa told him, leaning close to his ear. "Please don't leave me alone here in the middle of the sea! Hang on just a little longer and we will be in Europe together." She noticed that his face was turning from yellow to blue. He said, "Allah, give Doaa my spirit so that she may live."

Doaa realized Bassem was losing consciousness. Through her tears, she managed to utter a promise: "I chose the same road you chose. I forgive you in this life, and in the hereafter we will be together, as well." Doaa gripped Bassem's fingers with her right hand, while her left arm braced Malak.

After some time, she felt his hands slip from her grasp, and she watched him go limp and slide into the water. Doaa desperately tried to pull him back to her, but he was beyond her reach. She couldn't get to him without losing hold of Malak. She cried out for him over and over, sobbing. She had lost the most precious person in her life and she wanted to die with him. She imagined letting herself slip through the inflatable ring and into the sea. But then she felt Malak's tiny arms around her neck and realized she alone was responsible for this child. Doaa knew that she had to try to keep her alive.

It was now Thursday afternoon; six days had passed since they'd left Egypt. Among the 25 or so survivors was a family Doaa had met on the boat with two young girls, Sandra and Masa. They were all wearing life jackets, which were keeping them above water, but Sandra was having convulsions. Her father was holding her, speaking in a low voice through his sobs. Doaa thought she saw the girl's soul leaving her small body as she went limp. Sandra's mother swam toward doaa, holding her young daughter, Masa.

She grabbed on the side of Doaa's ring, looked directly into her eyes, and said, "Please save our baby. I won't survive." Without hesitation, Doaa reached for Masa and placed her on her left side, just below Malak who now had her head nestled under Doaa's chin. She's probably not even 2 years old, Doaa thought, stroking Masa's hair and wondering if her small ring would keep all three of them afloat. A loud wail pulled Doaa away from her thoughts; Sandra was dead, and her parents were weeping beside her floating body. Just minutes later, the father's body went slack, as well. He had given up. The wife looked on in disbelief. "Imad!" she cried. Then, suddenly, she too went silent and passed away right before Doaa's eyes.

Al Zamel and her mother Hanaa are reunited in Sweden 2016

As night fell, the sea turned black , shrouded with heavy fog. The girls began to shift restlessly and cry, and Doaa did her best to calm them. She was afraid to move her aching arms in case she lost her grip on them. When the girls became agitated, she would sing them her favorite nursery rhyme, "Come on sleep, sleep, let's sleep together, I will bring you the wings of a dove." She also invented games with her fingers to distract them. She discovered that Malak was ticklish under her chin and would laugh when she played a game where she would use her fingers to pretend a mouse was running up Malak's chest and onto her neck. When the girls fell asleep, Doaa would rub their bodies to keep them warm, and when she thought that they might be losing consciousness, she would snap her fingers near their eyes and speak firmly: "Malak, Masa, wake up, sweethearts, wake up!" The only word Masa said back to her was "Mama." Doaa felt such a deep connection to these children that she began to feel as if she were their mother now. Their survival meant more to her than her own life.

The chemical tanker CPO Japan was sailing across the Mediterranean toward Gibraltar when a distress call came in from the Maltese coast guard: A boat carrying refugees had sunk, and the coast guard was requesting that all available ships provide assistance.

The captain of the Japan changed course, but when it reached the coordinates given in the distress call, all the crew saw were scores of bloated corpses floating.

Malak's grandfather touched Malak's face and said, "My little angel, what did you do to deserve this? Poor thing. Good-bye, little one; forgive me; I am going to die.

The captain thought he had done his part in answering the distress call and that no one would blame him for turning his ship around. But as he looked at the dead bodies float- ing around him, he decided to order the crew to release a lifeboat into the sea. The crewmen circled the area but found only more corpses. It seemed their search was in vain until the captain's voice crackled over the radio. Back on the ship, a watchman had heard a woman's voice calling for help. Somewhere out there, someone was alive. The men in the lifeboat headed toward the bow, hoping to locate the source of the pleas. Every now and again they could make out the faint echoes of a woman's voice, but it seemed to come from a different direction each time. "Keep yelling!" they shouted. After four days and nights in the water with nothing to eat or drink, Doaa's strength was failing. Her arms ached, and she was so dizzy that she was afraid she would pass out. She could no longer feel her lower legs, and her throat was raw from calling out. She wanted to give up, but the weight of Masa and Malak resting on her chest filled her with determination. She kept paddling to stay afloat, and with each push of her hand through the water, she would call out, "Oh, God! Ya, Rabb! " again and again.

She could see that a searchlight was scanning back and forth over the waves, and each time she cried out, the light would sweep closer to her. She willed the bright beam to illuminate her ring as she hurriedly paddled toward it. The girls were barely moving now and beginning to lose consciousness. Doaa splashed water on their faces to keep them awake and steered her way around the corpses and closer to the sound of her only hope.

Finally, after two hours, a sailor looking out of the window of the lifeboat cried, "I see her!" Suddenly, the spotlight swiveled toward Doaa. A futuristic red capsule the size of a small bus floated before her. At first, she thought she was imagining it; it looked nothing like any boat she'd ever seen. The men on board gazed down at her. They seemed shocked to see such a slight young woman afloat on an ordinary inflatable ring.

Al Zamel receives an award for her bravery from the Academy of Athens, 2014.

When Doaa reached the boat, the men grabbed her arms and legs to try to hoist her inside, but she resisted. Frantically, she pointed at her chest to reveal the two small children pressed against her. The men were astonished. Not only had this fragile-looking woman survived when so many others had died, but she had somehow managed to keep two young children alive, as well. They lifted all three to safety.

In the summer of 2015, almost one year after she had been rescued, Doaa was living in Greece, still struggling with her grief, nightmares, and the fear that she would never move forward with her life. One day she went on a picnic to the beach. After she finished eating, on an impulse, she stood up, kicked off her sandals, and walked into the sea until it reached her shoulders. The water was clear and cool and still. She stood there holding her breath, then calmly let her body sink down until the water covered her head for a few moments. When she returned to the shore, she looked back out at the horizon and thought, I am not afraid of you anymore.

Editor's note: Malak died aboard the CPO Japan shortly after being rescued. Doaa and Masa were two of just 11 survivors of the shipwreck. Masa was eventually reunited with Syrian relatives in Sweden. In January 2016, Doaa, 21, also resettled in Sweden, along with her mother, father, brother, and two sisters.

Adapted from A Hope More Powerful Than the Sea, by Melissa Fleming, to be published on January 24. Copyright © 2017 by the author and reprinted by permission of Flatiron Books, a division of Holtzbrinck Publishers Ltd.

This article appears in the February issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

-

The Scent of the Summer Is a Little Bit Pool Water, Plus a Lot of Swimsuit Lycra

The Scent of the Summer Is a Little Bit Pool Water, Plus a Lot of Swimsuit LycraVacation’s new body mists are coming in hot.

By Samantha Holender

-

In 'Sinners,' Music From the Past Liberates Us From the Present

In 'Sinners,' Music From the Past Liberates Us From the PresentIn its musical moments, Ryan Coogler's vampire blockbuster makes a powerful statement about Black culture, ancestry, and art.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Kendall Jenner Has the Last Word on the Best Travel Shoes

Kendall Jenner Has the Last Word on the Best Travel ShoesLeave your ballet flats in your checked bag.

By Halie LeSavage

-

Black Lives Matter Quotes That Are Powerful, Informative, and Necessary

Black Lives Matter Quotes That Are Powerful, Informative, and Necessary"Racism is a visceral experience...It dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscle, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this."

By Katherine J. Igoe

-

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It Harder

Being Estranged From My Mom Is Hard. Mother’s Day Makes It HarderIt’s high time to start representing the different types of mother-daughter relationships—or lack thereof—that exist during the holiday.

By Christina Wyman

-

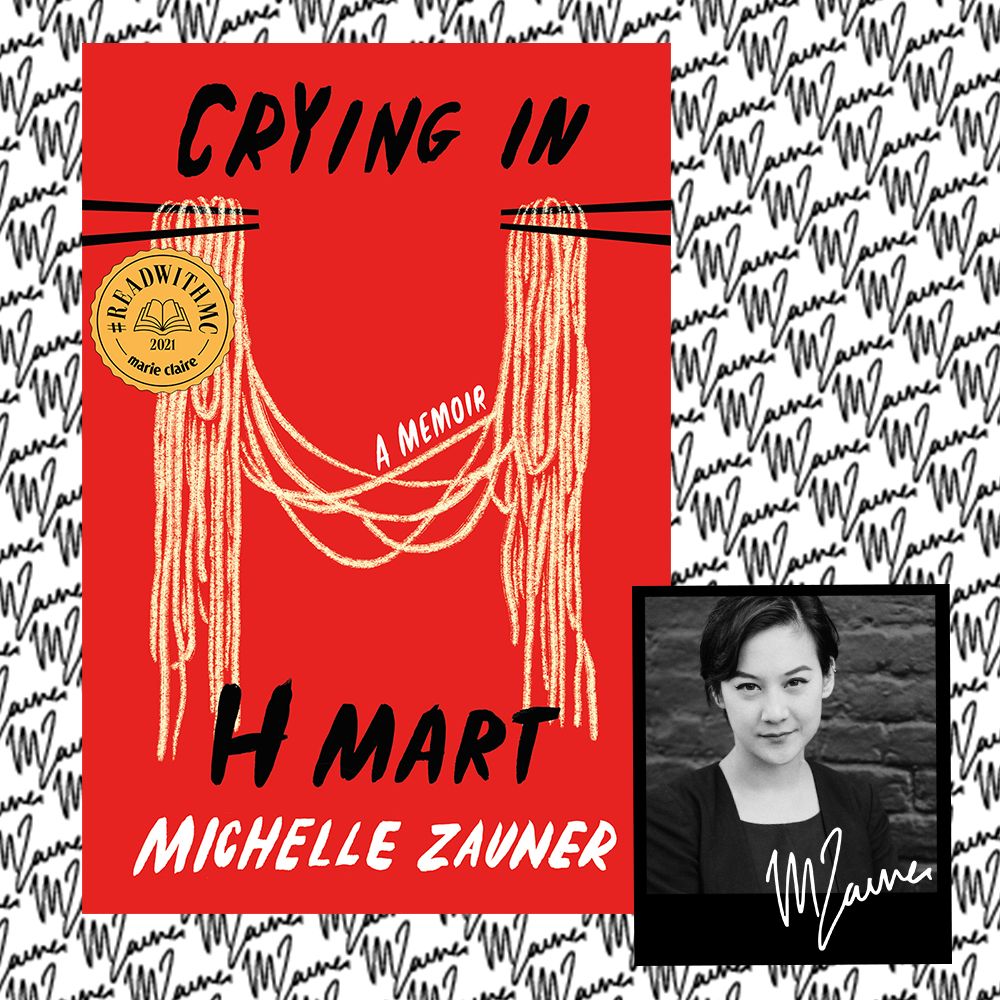

'Crying in H Mart' Is Our May Book Club Pick

'Crying in H Mart' Is Our May Book Club PickRead an excerpt from Michelle Zauner's memoir, here, then dive in with us throughout the month.

By Rachel Epstein

-

23 Black History Heroes You May Never Have Heard Of

23 Black History Heroes You May Never Have Heard OfThese are life stories worth knowing.

By Bianca Rodriguez

-

To End Sexual Abuse in Churches, Dismantle Purity Culture

To End Sexual Abuse in Churches, Dismantle Purity CultureThe Christian church’s norms provide the perfect cover for sexual predators—and leave their victims feeling like the sinners.

By Leslie Goldman

-

I Was Adopted by a Sex Offender

I Was Adopted by a Sex OffenderHow my stepfather's past changed my future.

By Sine Nomine

-

Where Did All My Girlfriends Go?

Where Did All My Girlfriends Go?How To Even in our hyperconnected world, true friendship remain elusive for young women looking to rebuild their college-era squads.

By Maggie Bullock

-

What It's Like to Grow Up in a Cult

What It's Like to Grow Up in a CultIn her new book, To the Moon and Back: A Childhood Under the Influence, Lisa Kohn describes her journey into and out of the infamous Unification Church.

By Megan DiTrolio