The Perils of Having an Infamous Name Twin

I wasn't charged with fraud, but some people think I was.

Nevermind what I have done in my life, let’s talk about what I have not done: I have not dropped out of Stanford University, started a secretive and much-hyped blood-testing company, had my net worth estimated at $4.5 billion, or been charged with fraud by the SEC.

That’s the other Elizabeth Holmes. She rocketed from relative obscurity to startup darling several years ago as the founder of Theranos. The company promised to revolutionize the medical industry with proprietary technology, gleaning a tremendous amount of information from a single drop of blood. She topped Forbes’s list of America’s Richest Self-Made Women in 2015 and appeared on the cover of its magazine, as well as the covers of Fortune, Inc., and Bloomberg Businessweek.

Her devotion to black turtlenecks, in the same vein as Steve Jobs, has soured me on the style.

Then it all came tumbling down: The Wall Street Journal published a series of stories beginning in late 2015 questioning the company’s claims and the accuracy of its tests. Her company neared bankruptcy, Forbes revised her estimated net worth to nothing, and last month the SEC charged her with “massive fraud." (In her settlement with federal regulators, Holmes neither admitted nor denied the charges, but gave up voting control of Theranos, agreed to a 10-year ban from being an officer or a director at a public company, and will pay a penalty of $500,000.)

I will confess to a tinge of Schadenfreude: Now neither of us are billionaires.

In the game of name twinning, I’m lucky. Unless you are an avid Wall Street Journal reader or otherwise curious about tech or healthcare news, you might not know about the other Elizabeth Holmes. Even since I’ve moved to Silicon Valley, where Theranos is based, it rarely comes up.

But her rise and fall has done lasting damage, namely (ahem) online. Her controversies have ruined my Google results, which I spent more than a decade building and relied on as a writer. Search our name and you can read all about her—you have to add a qualifier, like “journalist,” to find any mention of me or my work. Adding my middle name doesn’t help: “Elizabeth Ann Holmes” (me) redirects to “Elizabeth Anne Holmes” (her). (Also, her devotion to black turtlenecks, in the same vein as Steve Jobs, has soured me on the style.)

Plenty of others join me in my plight. I wonder how Elizabeth Holmes, the Seattle travel agent who lays claim to ElizabethHolmes.com, feels about all this. Another Elizabeth Holmes, who goes by Liz, slid into my Instagram DMs to ask, “Is there a support group?” My—or should I say our—name is more common than I realized: In the U.S., Elizabeth is the fourth most popular female given name of the last century, according to the Social Security Administration. Holmes ranks 171st on the list of frequently occurring surnames.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Indeed, the name pool is not quite as vast as you might think—the most common first and last names are held by millions of people. There have been more than 4.8 million people named James born in the last century, and nearly 3.5 million Marys. Of the roughly 6.3 million different surnames given in the 2010 census, 11 were reported more than a million times each.

Before the days of the Internet, one might go their whole life believing their name to be unique. But the web has made it much easier to find your name twin; and name confusion online can be a problem IRL, resulting in misfired emails, inaccurate search results, and social media firestorms. The 24/7 news cycle fans the flames, speeding up the time from unknown entity to household name.

Google the name “Stephanie Clifford” and you will be treated to a list of links about Stormy Daniels, the adult film star who reportedly had an affair with President Trump. Click on the Image tab and, among a sea of photos of the busty blonde, are two headshots of another blonde—another Stephanie Clifford, the novelist and journalist, smiling sweetly and dressed much more modestly.

This Stephanie Clifford first learned of her name dupe from her own self-Googling long before Stormy Daniels made the news. For a while, the identical identity was no issue—Clifford isn’t sure anyone else even made the connection. But when reports of an affair with the president broke earlier this year, Clifford’s phone exploded: first a text from a college roommate, then a dozen emails from friends and acquaintances asking how she was doing, followed by a flood of Twitter mentions.

“The Instagram and Facebook followers I’ve gotten who think I'm Stormy have been, like, absurdly nice about my definitively non-pornographic posts—'liking' my cat photos, giving positive comments on ephemera I'm researching at the library, one dude proposed marriage,” Clifford says. But she is a little nervous about her next round of book appearances, and the expectations attendees may have of meeting the porn star. “When they instead see me, a five-foot tall gal with an A cup, they're not going to be super psyched.”

The rapidly revolving door of the Trump administration has caught several name twins by surprise. "Nobody raided my apartment," tweeted Michael Cohen, the sportswriter in Wisconsin, on Monday after news broke that the FBI had raided the office and hotel room of Michael Cohen, the president's attorney. "I feel your pain, Michael," responded Rob Porter, also a sportswriter and not the departed, disgraced former White House staffer.

Name sharing has become something of a nightmare for Jason Kessler, a TV host and food writer, who shares his name with the white supremacist who organized the Charlottesville rally in August 2017. “My name is being used to incite and inflame bigotry,” he wrote in a piece for Salon last September. “I feel like my whole reputation has been destroyed.” The person who shares his name also calls himself a journalist. “Unfortunately, people don’t take the time to say, ‘Are you the racist one?’” he tells me. “Instead, I imagine people who make the error just write me off without realizing that they’ve made a mistake.”

“When they instead see me, a five-foot tall gal with an A cup, they're not going to be super psyched.”

The Internet is an imprecise place, so much so that you can get caught up in the crossfire if your name just sounds like someone else’s. Australian Lauren Ingram received the full extent of Twitter’s vitriol recently in response to the comments Laura Ingraham of Fox News made about a Parkland high schooler. Amongst the curse-laden misdirected replies were suggestions she change her name or dye her hair so she was no longer blonde like Ingraham.

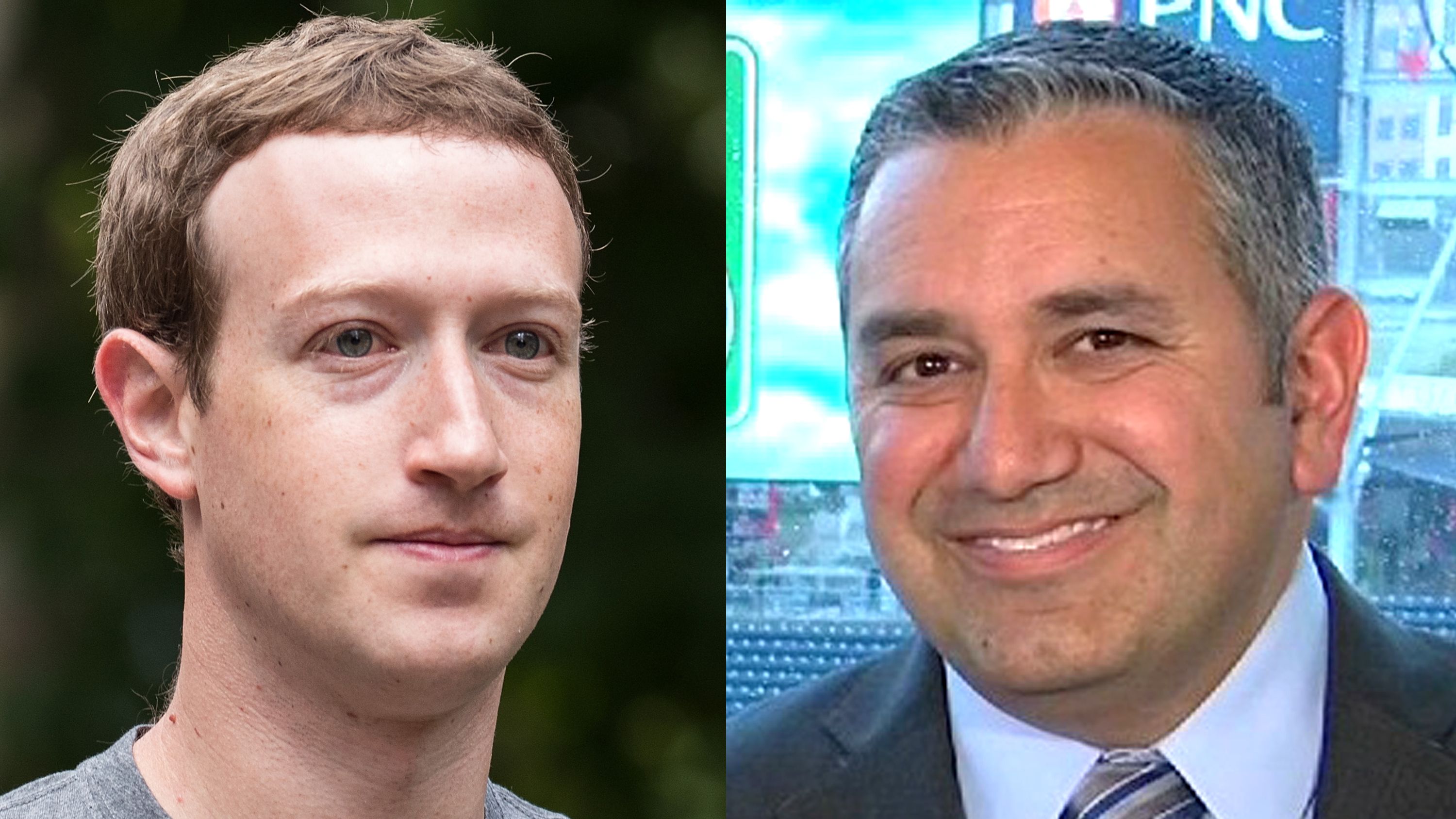

Mark Zuckerman, a sportswriter covering the Washington Nationals, saw his mentions take a nasty turn in recent weeks, after years of receiving tweets directed at Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook's founder. When the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke, Zuckerman was inundated with nearly 100 messages in a single day. His usual response is to laugh and occasionally retweet. “@MarkZuckerman must think we are ALL stupid,” read a recent tweet, to which Zuckerman responded, “No, only some of you.”

Last year, his colleague made a video with Zuckerman reading some of the tweets, in the spirit of Jimmy Kimmel’s famed mean-tweet segment. In response to the tweet “Y don’t u give away ur money?” Zuckerman looks at the camera and deadpans, “Because after the mortgage and daycare, nothing’s left.”

“My biggest fear is that he's going to end up running for public office,” Zuckerman tells me. “If that ever happens, I'm in serious trouble.”

Katie Perry, the Brooklyn-dwelling marketing consultant who is not the internationally renowned pop star Katy Perry, has come to expect a three-step reaction when she gives her name to someone, like when she picks up a salad she ordered online: First, there is the excitement over meeting a celebrity, then the disappointment at the confusion, and finally “laughing at my misfortune,” Perry says.

The pop star’s song, “I Kissed A Girl,” hit the charts during the other Perry’s senior year at Notre Dame. Some two years later, when “Teenage Dream” took over the radio waves—and the setlist at not-famous Perry’s go-to bar—she turned to a friend and said, “This is going to be a problem, isn’t it?”

But it hasn’t been, not really. Whenever Katy Perry is in the headlines—whether she’s feuding with Taylor Swift or stumping for Hillary Clinton—Katie Perry’s mentions flare up. It’s mostly friendly, although during the 2016 campaign she blocked a few folks on Twitter. Her friends have made a game of it, screen-shotting reports and sending them to her. “My all-time favorite?” she says. ‘John Mayer misses Katy Perry and wants children’—I almost framed that one.”

RELATED STORY

Elizabeth Holmes is a writer based in the Bay Area and the author of the forthcoming book HRH: So Many Thoughts on Royal Style. She spent more than a decade on staff at the Wall Street Journal, most recently as a senior style reporter and columnist; her work has also appeared in The New York Times, InStyle, Real Simple, and Town & Country.

-

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"Here's what to know about the Max series's breakout star, who just so happens to come from TV royalty.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an Apology

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an ApologyThe season finale of the smash Max series proved that the most unlikable character on TV may just be the hero we all need.

By Jessica Toomer Published

-

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 Million

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 MillionHulu's answer to 'The Traitors' is here.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Meet 'Selling the City' Star Jordyn Taylor Braff: What to Know About Her Career Trajectory and Dating History

Meet 'Selling the City' Star Jordyn Taylor Braff: What to Know About Her Career Trajectory and Dating HistoryShe even had a surprising career path before joining Douglas Elliman.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

32 Celebrity Podcasts Worth Listening To

32 Celebrity Podcasts Worth Listening ToGrab some headphones and tune in.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

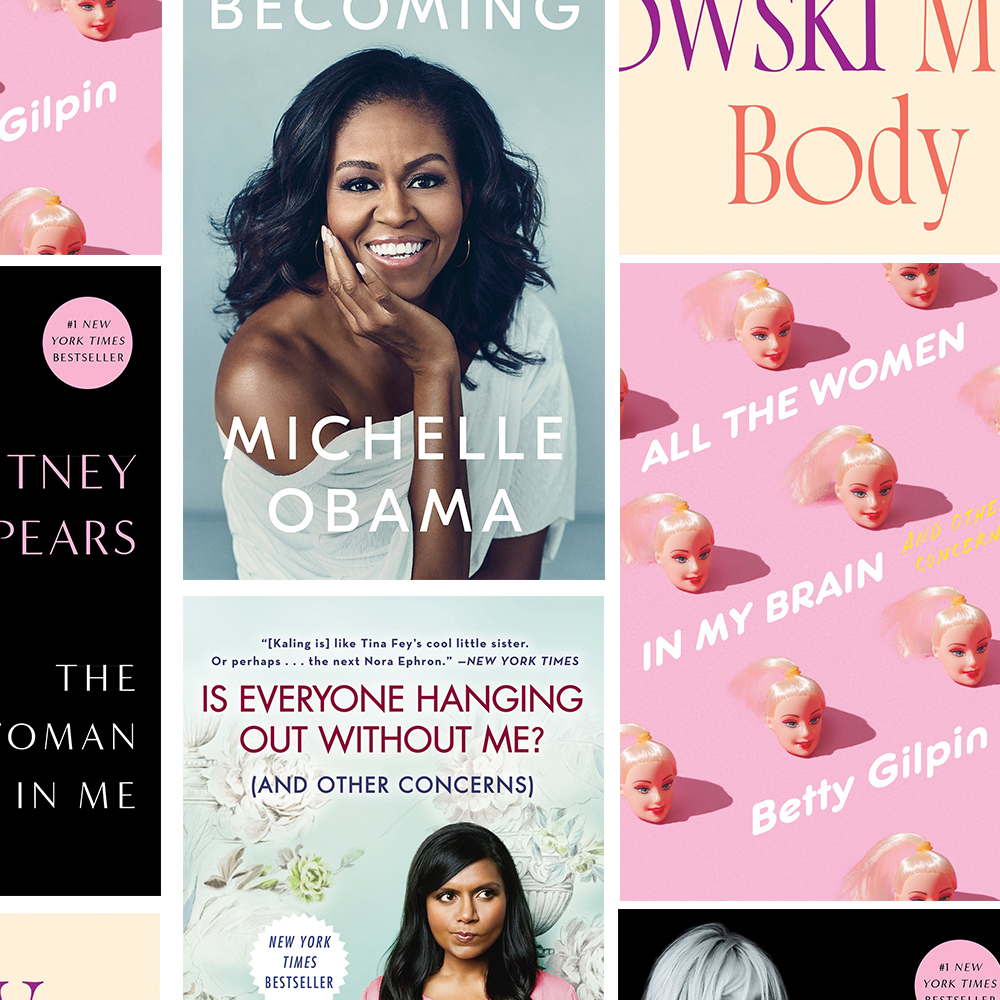

The 30 Celebrity Memoirs That Are Actually Worth Reading

The 30 Celebrity Memoirs That Are Actually Worth ReadingBritney Spears, Demi Moore, Jessica Simpson, and more drop some serious bombshells in these pages.

By Andrea Park Published

-

The Unstoppable Alia Bhatt

The Unstoppable Alia BhattBollywood’s silver-screen darling is both at the top of her game and just getting started.

By Neha Prakash Published

-

The 30 Best Movies on Hulu Right Now

The 30 Best Movies on Hulu Right NowFrom 'Fight Club' to '10 Things I Hate About You.'

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

Queen Elizabeth Has Passed Away at 96

Queen Elizabeth Has Passed Away at 96After a 70-year reign, the queen passed away at her home in Balmoral, Scotland.

By Jenny Hollander Published

-

Elizabeth Lail and Dustin Milligan Compete in 'How Well Do You Know Your Co-Star?'

Elizabeth Lail and Dustin Milligan Compete in 'How Well Do You Know Your Co-Star?'The stars of 'Mack & Rita' could barely hold it together during a round of trivia.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

Charli XCX Isn't Here to Appease Anyone

Charli XCX Isn't Here to Appease AnyoneThe pop star talks authenticity, her new album, and taking care of herself while on tour.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published