Why Is the Internet Still An Unsafe Place for Opinionated Women?

Trolling isn't just annoying—it's dangerous.

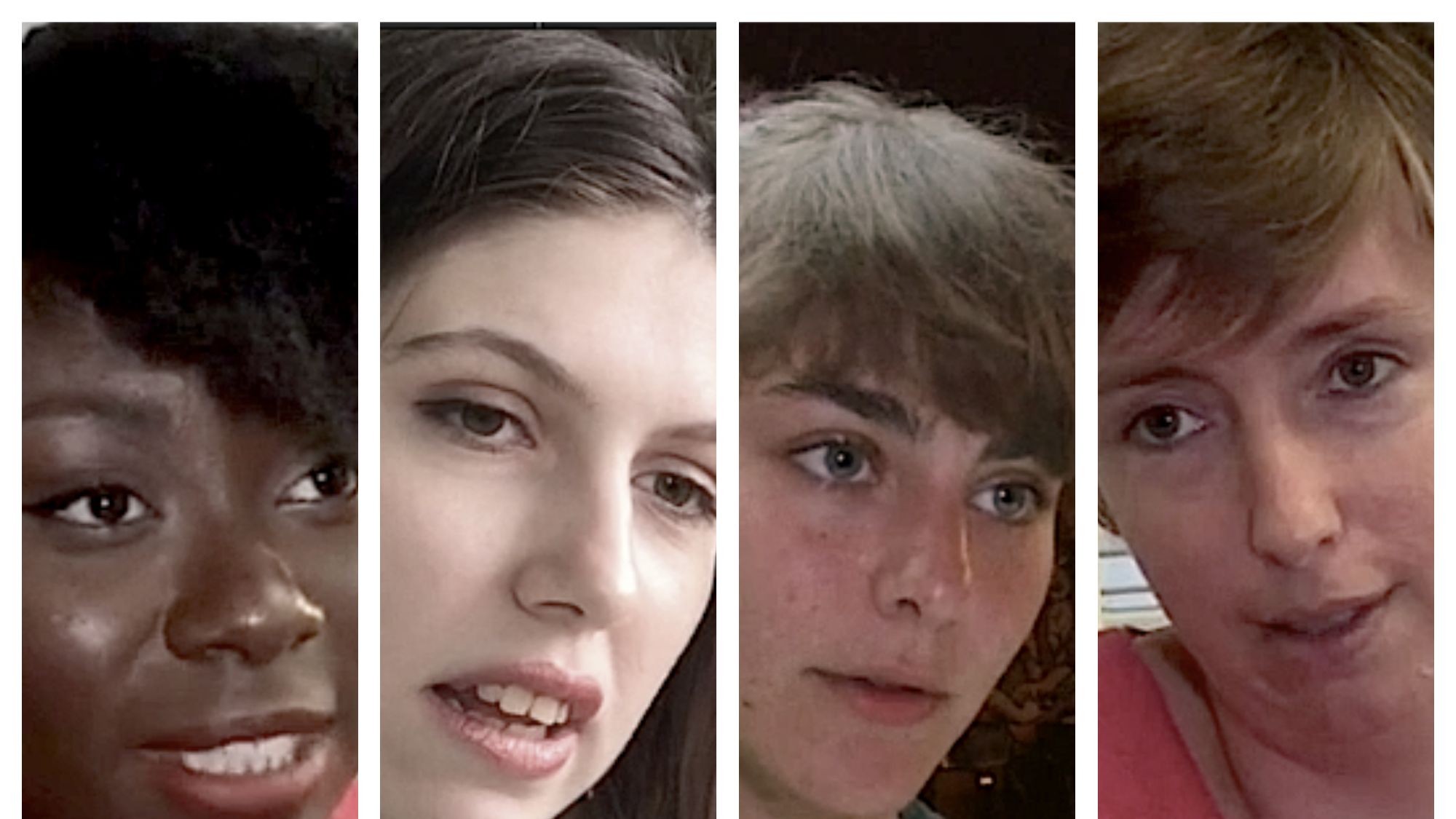

For MarieClaire.com’s Women Bylines series (a partnership with Gucci’s CHIME FOR CHANGE campaign), we documented the—somewhat risky—reality facing French women when they voice their opinion on the Internet.

“‘Whore,’ ‘journa-bitch,’ ‘tart,’ ‘go die’—all of these insults are for me,” says Anaïs Condomines, a journalist in Paris and the subject of the film Cyber Bullied: Tales of Impunity 2.0. “I’m regularly insulted and harassed on social media. I write about feminism and women’s rights. It’s a gold mine for harassers.” Last year, Anaïs Condomines published a story about a video game forum in which members lead anti-feminist raids and insult women for being too active online. When the piece ran, she was inundated with abusive comments and tweets (including death and rape threats) and her email was hacked. “This happens every day to female internet users.”

While men are not immune to online harassment—nor are they singlehandedly doing the bullying—online attacks are clearly a gendered issue. Two-thirds of women journalists worldwide have been the victims of harassment, according to a report by the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF). A quarter of this harassment takes place online. Men are primarily targeted for their opinions, but women are targeted for their gender and appearance. This abuse often takes the form of threats of sexual violence and extends to members of their families. “I receive death threats and rape threats, threats to go kill my family. There’s not much I can do on the internet anymore without being attacked,” says Marion Seclin, another woman featured in the film, who received an onslaught of digital attacks after creating a video denouncing street harassment. “A man made a video saying how stupid I was and asked people to lash out at me. There were waves of hatred. It became a war.”

American women are just as vulnerable to the internet’s toxicity—particularly in this volatile political climate. In fact, 26 percent of U.S. women ages 18 to 24 have been stalked online and 25 percent have been the target of sexual harassment online, according to a Pew Research Center Survey.

Lindy West, a writer in the U.S. who focuses on feminist issues and body shaming, has spoken openly about the online abuse she’s endured. “The worst incident ... was a man [who] made a Twitter profile pretending to be my father who had recently passed away,” she told Terry Gross, the host of National Public Radio's show Fresh Air. “He had his picture and was sending me really abusive messages and his bio said, ‘Embarrassed father of an idiot.’ I later had copycats of that guy. So I had more accounts pretending to be my dad, telling me he was ashamed that I had written about having an abortion.” West deleted her Twitter account in early 2017. Laurie*, a journalist in New York who reports on abortion rights, received severe backlash after sharing a story about clinic workers. “A guy found me on Facebook to call me a feminist bitch who needed to be f***ed harder.” It might be easy to downplay one or two nasty remarks, but the cumulative effect of harassment (online or off) is traumatizing.

So what happens when you can’t take it anymore? A troubling consequence of this ongoing abuse is that women are apt to remove themselves from the public conversation (out of fear, anger, or just plain exhaustion). Put simply, trolling is a systematic silencing mechanism. “A lot of women have stopped speaking,” says Lauren, another female reporter interviewed for the film. “But if we all stop, who is going to speak for us?”

*Name has been changed.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.