The Scary Future of Date-Rape Drugs—and Why Their Perpetrators Are So Hard to Bring to Justice

How do you prove a crime occurred when there's no evidence and the victim has no memory? Whether in the national spotlight like the Bill Cosby allegations or in the shadows of a college campus, date-rape-drug perpetrators are painfully difficult to prosecute. Here, a deep dive into why.

One spring morning a couple of years ago, Megan* woke up from a deep sleep, lying in bed next to a man she didn't know, in an apartment she didn't recognize, wearing only a bra and a pair of jeans. She asked the stranger next to her, "Who are you? What is your name?" and then, "Did you have sex with me last night?"

"Yeah," he answered. "You were totally asking for it."

The night before, Megan, who at the time was a college student in her early 20s, had gone out with friends to a bar. She spent most of her time nursing a beer, bored by the scene around her. Her friends struck up a conversation with a group of guys who were members of one of the school's fraternities. Megan, a lesbian, couldn't have been less interested, ignoring the guys in favor of texting her girlfriend. The last thing she remembers is taking a sip of her friend's cocktail.

No way would she have "asked for it," Megan thought—she didn't sleep with men. Despite feeling angry and frantic with anxiety, she stiffly accepted the man's offer for a ride from his apartment to her friend's home near campus. "I thought I could gather more information about him," she explains. She never learned his name, but made a mental note of his license plate number and car model.

"Who are you? What is your name?" "Did you have sex with me last night?"

When Megan arrived, she bounded up the stairs into the top-floor apartment, where the friends she had gone to the bar with the night before were sleeping. She found them huddled in bed and woke them up. "What happened to me last night?" Megan asked. "The same thing happened to us," her friends replied. Like Megan, her friends remembered nothing from the previous night, but had had sex with members of the fraternity. "We were obviously drugged and then raped," Megan says.

About 10 hours after the women had those last sips of booze, a friend drove them to a nearby medical center. "They were in shock," the friend says. "I was so angry I couldn't sleep for days." At the hospital, the girls told the receptionist that they needed rape kits. "All of you?!" Megan recalls the receptionist exclaiming. Medical staff tested her urine but not her blood or hair, which can also determine if drugs are present. After two days of being unsure what to do, the women went to the police. Later that day, using the information Megan had gathered, the police identified and arrested the man she had accused of drugging and raping her on charges of forcible sexual assault. But when her toxicology reports came back clean, the district attorney decided not to prosecute.

"[The toxicology report] was the missing piece," the prosecutor says. "Megan was unable to recall any detail about the incident that would prove beyond a reasonable doubt whether there was a lack of consent or whether her ability to consent was impaired. There was also no evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the suspect had actual knowledge that Megan was incapable of giving consent to the sexual contact, or that if in fact Megan was impaired, that the suspect was the one responsible for her impairment." The other friends dropped their cases. "I wasn't shocked, but I was angry," Megan says. "I felt it was one less case for them to worry about."

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

She is hardly alone. While no research exists on just how common what is known as drug-facilitated sexual assault is, experts suspect the number of incidents is much greater than we realize. "We get a huge array of anecdotal reports—people contacting the National Sexual Assault Hotline and reporting that they were drugged," says Scott Berkowitz, president of the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), a national nonprofit based in Washington, D.C. This year, in response to the accusations from more than 50 women who have come forward to accuse comedian Bill Cosby of drugging and sexually assaulting them throughout the course of four decades, RAINN's hotline has seen a 50 percent increase in calls. "Many sexual assault survivors found the women's allegations familiar—hearing from someone who has survived a similar experience can be incredibly encouraging to those who have yet to come forward," Berkowitz says. "But as far as how common it is, the honest answer is, we don't know. It certainly seems to be more prevalent than the number of prosecutions would suggest, based on reports from victims, but we have no good way to quantify just how many cases there are."

"I was so angry I couldn't sleep for days."

Such high-profile cases suggest we may just be at the tip of the iceberg—one that we're virtually powerless against because such cases are extremely difficult to successfully investigate and prosecute. The first victim to come forward to accuse Cosby of sexual assault was Andrea Constand, then the director of operations for the women's basketball program at Temple University in Philadelphia, who filed a lawsuit in 2005 alleging that the comedian had drugged and molested her. In a court deposition that year, Cosby admitted to giving at least one woman quaaludes, a sedative, but insisted the resulting sex was consensual. The Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, district attorney's office declined to file criminal charges against the comedian, citing a lack of evidence. (The vast majority of Cosby's accusers will never get their day in court since the statute of limitations, which varies by state, has expired in most of the cases. One civil lawsuit filed by a California resident named Judy Huth, who says she was molested at age 15 by Cosby at the Playboy Mansion, is pending. Civil cases have a lower standard of proof than criminal ones—"a preponderance of evidence" instead of "beyond a reasonable doubt.")

Last October, the singer Kesha filed a lawsuit against her producer Dr. Luke (full name Lukasz Gottwald) in which she accused him of giving her GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyric acid) and raping her. (Dr. Luke filed a counter lawsuit against Kesha alleging that she made up the abuse claims to get out of her contract.) In March, retired NFL player Darren Sharper, a former safety for the New Orleans Saints, pleaded guilty to drugging three women in New Orleans with substances including Ambien, the prescription sleeping pill that can cause incapacitation and memory loss, before sexually assaulting them. (When Sharper was arrested in January 2014, he reportedly had 20 Ambien pills in his possession; his sentencing is pending.)

So-called date rape drugs, including Rohypnol and GHB, as well as prescription painkillers and sleeping pills, are in many ways the perfect weapons. Most are odorless, colorless, and tasteless, and leave the body within a few hours. Many also wipe a victim's memory, so even if sex occurred and there's physical evidence (like a used condom), proving the sex wasn't consensual is nearly impossible. And most standard rape kits—the medical examination victims are given to collect evidence of an assault—don't include a toxicology test, the only way to screen for such substances. If a doctor or Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner decides to order one based on the initial interview and exam, the victim's urine—which is the most reliable and cheapest way to screen for drugs—as well as their blood, is screened. Depending on such factors as dosage and a victim's weight, such tests can be effective at detecting Rohypnol if administered within 24 hours but aren't likely to show the presence of other forms of date rape drugs, like GHB. Detecting an elevated level of GHB, which is naturally produced in the body, requires a sophisticated forensic analysis of a victim's urine that most hospitals are not equipped to handle. As for sleep aids and painkillers, most leave the body shortly after consciousness is regained.

"The body is very efficient at clearing drugs from the system," says Dr. Randall Brown, the medical examiner on sexual assault cases for the district attorney's office in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. "You wake up and go to the bathroom, not really realizing something may have happened. [That's how] we lose the first specimen of urine, where our evidence could be." Hair tests can also be effective, as many drugs stay in the shaft from a few days to several weeks. But because the symptoms most date rape drugs cause are similar to alcohol, doctors may falsely assume the victim has just had a lot to drink and decline to run the additional tests. "Unless you do all the testing and do the right testing," Brown says, "you may not come up with anything."

With no record of drugs in the system and no recollection of the assault, victims are often left with little recourse. Because many rape cases come down to little more than "he said, she said," convictions are hard to obtain (for every 100 rapes, only 32 are reported to the police, and of those, only two rapists will serve time, according to RAINN). But when drugs are involved, the case turns into "he said, she can't remember"—basically a nonstarter in court, where rape, a felony offense, must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

Because of this, prosecutors may decline to bring drugged rape cases to trial, says Joni Leventis, who heads Alameda County, California's district attorney's sexual assault unit. "Many DA's offices shy away," she says, "[because] these cases are not tied up in a bow." Leventis has successfully prosecuted date rape drug cases by bringing in medical experts to testify about how people can be drugged and still have a clean toxicology report. So has Linda Fairstein, the former prosecutor who headed the sex crimes unit of the Manhattan DA's office for 26 years. "A good, aggressive prosecutor has to be creative when you have nothing but a victim's story. We've done what's called a 'controlled phone call,' in which we write scripts for the victim to ask her perpetrator: 'I need to know why you did that to me.' If six months go by, he may be complacent, he thinks he's smarter than she is and says something incriminating. Maybe a victim's roommate says she couldn't wake her up for hours—these are pieces of circumstantial evidence prosecutors can use to build their cases."

With no record of drugs in the system and no recollection of the assault, victims are often left with little recourse

But successful prosecutions are not the norm: Many perpetrators are never punished, and worse, they may be emboldened by the lack of consequences. "People who commit these types of crimes realize they can get away with it and do it with impunity," says RAINN's Berkowitz. "They do it more and more because there is nothing stopping them … They hone their technique over time and do everything possible to make sure they are undetected."

All Megan remembers from that night is taking that last sip of her friend's drink. Almost immediately, she began to feel dizzy and her eyesight became blurred, like "tunnel vision," she says. After that: nothing. "I don't even remember leaving the bar," she says. "For that, I'm kind of grateful—I don't have to live with those memories."

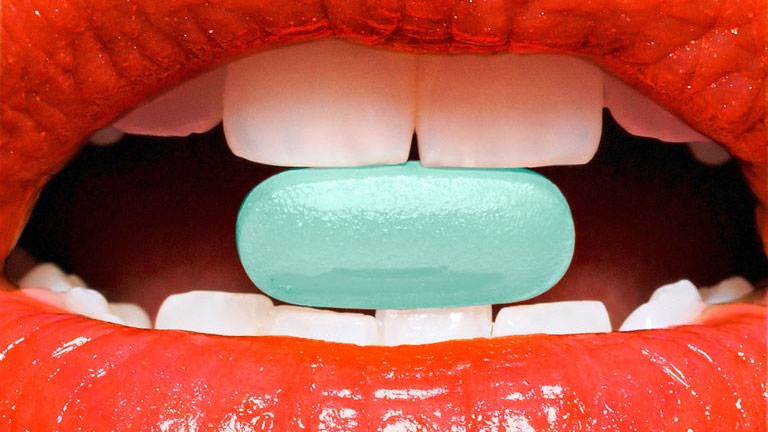

That's how date rape drugs work. The pills can be easily ground up so they are ready to be mixed into a drink in the time it takes for a woman to visit the bathroom. Once ingested, they are absorbed into the bloodstream in a matter of 15 to 30 minutes, disarming the victim, who, depending on the dosage, could act either completely normal (if anything, they may be slightly sleepy or confused) or appear very intoxicated. Victims may feel dizzy, slump over, or need help walking, and their speech may be slurred—all things a perpetrator may use as an excuse to "help" the victim. Many victims also suffer what is known as anterograde amnesia, which means they can participate in conversations, etc., but later have no recollection of the events. It's almost like being a baby: Victims can laugh, eat, and talk, but nothing is stored in the memory. Some may also experience retrograde amnesia, which means they could forget things from before they were drugged.

One of the most popular date rape drugs, Rohypnol, or "roofie," is so widespread, its nickname is often used as a catchall phrase when victims describe being drugged. Rohypnol was first developed by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-La Roche in 1975 and was widely used by hospitals across Europe and Latin America as a preanesthetic, given a couple hours before an operation to calm patients and reduce their memory of the procedure. But during the 1990s, the drug started showing up in rape investigations. Back then, Rohypnol was a small white tablet that could be crushed and dissolved into a drink without altering the color or taste of the contents. But in 1997, after repeated reports of the drug being used to rape women, Hoffmann-La Roche reformatted the pills to be olive green in color with a blue core. Now, if Rohypnol is added to a clear drink, the core will turn the liquid blue, but if added to a dark drink, it may not be noticeable.

GHB, the other most common date rape drug, comes in liquid or powder form. It was marketed in the late 1980s as a dietary supplement to promote weight loss and build muscle, but was taken off the market in 1990 owing to safety concerns (seizures, coma, death). Both drugs are illegal in the U.S. Rohypnol was labeled a Schedule IV controlled substance in 1984 and is not approved for manufacture, sale, or use in the country. Similarly, GHB was labeled a Schedule I controlled substance (like marijuana and heroin) in 2000, meaning it has no accepted medical value. Today, they both have only one use: "These drugs are used with the intent to do harm against somebody," says Eduardo A. Chávez, a special agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

But outlawing the drugs has not effectively removed them from the streets. According to Chávez, Rohypnol is mostly smuggled in through Mexico, where it is legal, and sold for about $20 a pill. GHB can easily be made in a standard kitchen, he says. Numerous websites hawk the drug online for as little as $5 a capful (more than enough to incapacitate a 5'3", 166-pound woman); some sellers label it as a window cleaner, fish tank cleaner, or ink remover.

Over the past several years, Chávez says the DEA has investigated several dozen cases involving Rohypnol and GHB, but cracking down on the drugs is an ongoing challenge. Dealers are spread across the country. Many are individuals instead of criminal networks, which are easier to track. And most deals take place anonymously online on message boards and in chat rooms, with the dealers buying small amounts at different times from different sellers rather than in bulk. "The stakes are very high when it comes to drugs that are commonly used hand in hand with sexual assault," Chávez says. "[But] really niche organizations sell these drugs … It's like trying to find a specialty piece of equipment and scouring the Internet."

Numerous websites hawk the drug online for as little as $5 a capful; some sellers label it as a window cleaner, fish tank cleaner, or ink remover.

Perpetrators have also turned to prescription pills like Ambien, Valium, or Xanax. In particular, Ambien, a common sleep aid, is known to erase memory and has been called a "roofie" replacement. Its flavor can be masked in a glass of wine, and victims can be incapacitated by a standard dose. And as anyone who's ever "borrowed" an Ambien from a friend before a long flight knows, it's not hard to find.

For women hoping to ward off a drugged assault, RAINN says the best defense is to be familiar with the warning signs (nausea, difficulty breathing, feeling drunk when you haven't consumed much alcohol, dizziness, temperature change, among others). Those who suspect they may have been a victim of a drugged assault can take steps to preserve evidence for an investigation. If you can't get to a hospital immediately, RAINN suggests saving urine in a clean, sealable container as soon as possible, and storing it in a refrigerator or freezer. The National Sexual Assault Hotline (800-656-HOPE) can help locate a hospital or medical center where a sexual assault forensic exam can be conducted and where blood and urine can be screened.

After the district attorney declined to take up the criminal case, Megan reported the rape to the university. Some nine months later, the university, too, ruled against her, saying there was not enough evidence to prove that a crime occurred. The man Megan says raped her remained a student.

In the months after she and her friends reported their alleged assaults, a handful of other students came forward with similar drugging allegations against members of the same fraternity. None of the fraternity members contacted by Marie Claire responded to repeated interview requests; most have graduated since the reported incidents. In a letter to Marie Claire, an administrator at the university said, "Any incident of suspected drugging is unacceptable, but [our university] has had very few incidents relative to its size."

Megan graduated from college as planned. She has drifted apart from the friends who were with her that night. She feels that her attacker and the other men got away with what they did, and nobody—not the school, the district attorney, the police—cared what happened to her and her friends. "I went through all this with no difference at the end," she says. "There has been no justice." Today, she still has no memory of what happened to her that night.

*Names and some identifying details have been changed for privacy.

KETAMINE STREET NAMES: Cat Valium, Green, Honey Oil, Special K. KNOWN FOR: Used by veterinarians to sedate animals. WARNING SIGNS: Very fast-acting, zombie state, hallucinations, feeling out of control.

AMBIEN STREET NAMES: Zombie Pills, Tic-Tacs, A-minus. KNOWN FOR: Sleep aid used by NFL player Darren Sharper to knock out his victims. WARNING SIGNS: A metallic taste, drowsiness, light-headedness, blurry vision, problems driving.

XANAX OR VALIUM STREET NAMES: Benzos, Downers, Candy. KNOWN FOR: An Indiana-based ob-gyn was convicted of injecting a woman with Valium and raping her in 1992. WARNING SIGNS: Paranoia, muscle weakness, seizures, slurred speech.

This article appears in the November issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands now.

Cara Tabachnick covers global crime and justice, including reporting on drugs, trafficking, police, violence, and prisons for publications ranging from The Washington Post to Bloomberg Businessweek. She splits her time between New York and Spain.