The Secret Career Genius of Marilyn Monroe

The icon is known for many things, but her groundbreaking transformation of the entertainment industry isn't one of them.

Thanks to years of sexist stereotypes, "Marilyn Monroe" and "feminism" rarely appear in the same sentence. But a closer look at her life reveals a thoughtful, progressive woman years ahead of her time. In fact, she once challenged Hollywood in an epic battle, shattering boundaries and changing the course of American cinema along the way.

Monroe rose to fame in the early 1950s, the zenith of Hollywood's Studio System. Back then there was one way to make it as an actor: Sign with one of the "Big Five" (MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, RKO, or, in Monroe's case, Twentieth Century Fox) and resign yourself to years of glamorous indentured servitude. Forget about talent, creativity, or even free will—the studio controlled your every move, from the roles you accepted to the directors you worked with to how often you went to the bathroom and occasionally even whom you married. The Big Five all owned theater chains, virtually ensuring that their films would be bought, regardless of quality. Actors and directors were mere cogs in the wheel, forced to churn out formulaic trash against their will for decades. No one dared to defy the studio moguls—except for Monroe, who, in 1955, rattled the system to its brittle core.

Monroe's big breakout was just two years prior. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire, both released in 1953, cemented her status as a bona-fide super star. At 27, she was the most popular actress on earth—yet still the property, essentially, of Twentieth Century Fox. Executive producer Darryl Zanuck humiliated and harassed her, forced her into bimbo roles—vacant stock characters with even flimsier scripts. Overworked and depressed with no end in sight, Monroe was breaking down. She'd often collapse on set, weakened by viral infections, bronchitis, and anemia. "An actress isn't a machine," she told Life magazine writer Richard Meryman, "but they treat you like one."

Monroe deserved better from Fox, and she knew it. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was their highest grossing film to date, earning more than $5 million worldwide ($50 million in today's dollars). Surely they'd give their power earner a raise, some respect, and a little independence. She longed to challenge herself, to take on meatier roles, like the lead in playwright Henrik Ibsen's Hedda Gabler or Grushenka from Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. She'd just finished reading Emile Zola's Nana—the perfect novel, she thought, for a film adaptation. Flush with the promise of her new idea, she called all the directors she knew…and each one declined. No one, it seemed, took risks. No one bucked the status quo of quotidian kitsch. Even George Cukor—a "women's director" and good friend—balked, fearing a film about a 19th century syphilitic prostitute might turn off Monroe's core (i.e. male) audience.

Besides, Zanuck already had her lined up for River of No Return, a formulaic Western with a sloppy plot. Bound by her contract, Monroe submitted with clenched teeth: "I think I deserve a better deal than a grade-Z cowboy movie in which the acting finished second to the scenery," she said.

The next time Fox presented her with an idiotic script, Monroe flung it back with "TRASH" scrawled on the title page in heavy black marker. Zanuck's secretary sent her an ominous telegram ordering her to report for work. Monroe ignored it. Production day came and went and still no sign of Monroe. Her agents called, Fox lawyers called, even Zanuck made threatening calls. But their star was already on a plane to New York, dressed in dark glasses and a black bobbed wig, traveling under the name of Zelda Zonk.

An actress isn't a machine, but they treat you like one.

Monroe had done the unthinkable: Break her iron-clad contract with Twentieth Century Fox. Somehow she'd managed to escape them—even if she'd had to fly across the country to do it. With the financial backing and moral support of her friend and photographer Milton Greene, she founded Marilyn Monroe Productions, jettisoned her agent, and formed a new East coast crew. In a matter of hours, she'd turned Hollywood upside down—and became the first woman since Mary Pickford to start her own production company.

Furious at being defied, Fox bombarded her with lawsuit after lawsuit and a hefty dose of "you'll never work in this town again!" When that tactic failed to scare her back to L.A., they resorted to bullying. "She's on her way out," sneered one of their lackeys to a journalist. "A year off the screen and she'll be washed up! We can find a dozen like her!"

Monroe laughed off the insults and immersed herself in New York City. She attended Broadway plays, danced with Truman Capote, and drank whiskey with writer Carson McCullers. She jogged in Central Park and spent hours admiring Rodins at the Met. She took classes with the legendary drama coach Constance Collier, walked along the East River at dusk, attended poetry readings, befriended playwrights, read James Joyce on Fire Island. She found a therapist she trusted who encouraged her to journal. Above all she pushed herself—as an actress and an artist.

She even joined the rarified Actor's Studio, a prestigious workshop on West 44th Street where Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, and Ellen Burstyn sat on folding metal chairs, eyes fixed on their formidable leader Lee Strasberg. L.A. glitter meant nothing in those dusty, bare rooms, where starlets were eyed with chilly suspicion. Blockbusters and box office numbers were irrelevant; you earned respect at the studio—no one walked in with it. "The Actors' Studio was more important than getting a job in Hollywood," member Ben Gazzara has said, "even more important than getting good reviews on Broadway. To get into the Actors' Studio was the max. When Monroe and people like that were invited in without the rigorous auditions we youngsters had to go through, we resented that quite frankly."

But after months of hard work and relentless study, Monroe won over her colleagues and blew them away with a knock-out performance as the lead in Anna Christie. (Ellen Burstyn still says it's the best one of all time.)

Monroe hadn't just won her autonomy—she'd made history.

By the year's end, she was being courted by Arthur Miller, photographed by Cecil Beaton, and praised by Tennessee Williams. The acclaimed director Josh Logan wanted her for his new film Bus Stop. And she'd purchased the rights to The Prince and the Showgirl—directed by and co-starring Sir Laurence Olivier. It would be the first film produced by Marilyn Monroe Productions.

On New Year's Eve, 1955, Fox finally surrendered. The lawsuits were thrown out and her salary boosted to $100,000 per film. But the biggest coup of all was creative control: She'd won story approval, director approval, even cinematographer approval. At a time when the studios wielded absolute power, this was revolutionary. Monroe hadn't just won her autonomy—she'd made history.

The press celebrated right along with her. The Morning Telegraph was the first to broadcast her victory: "BATTLE WITH STUDIO WON BY MARILYN," read the headline. "ACTRESS WINS ALL DEMANDS. The bitter battle is over—Marilyn Monroe, a five-foot-five-and-a-half-inch blonde weighing 118 alluringly distributed pounds, has brought Twentieth Century Fox to its knees." Time remarked on her skills as a "shrewd businesswoman," and the Los Angeles Mirror lauded her victory as "one of the greatest single triumphs ever won by an actress."

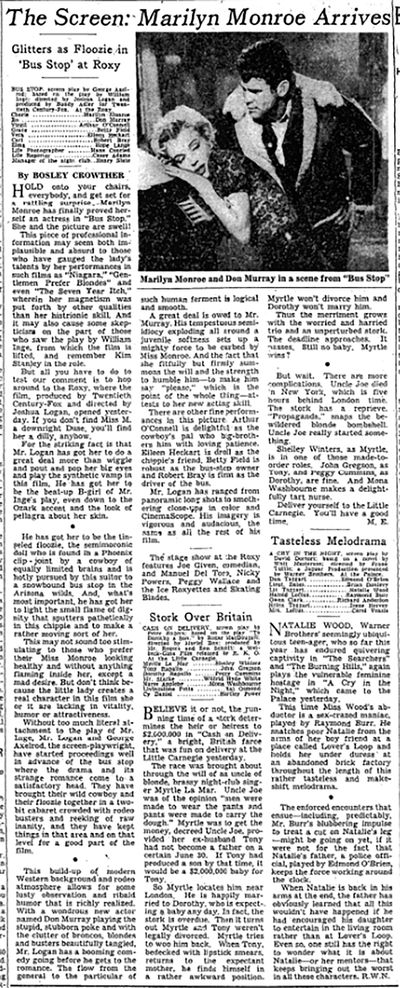

Free from the hack jobs that demeaned and depressed her, Monroe flew back West to begin filming Bus Stop. She'd play Cherie: a faded chanteuse in a honkytonk town with an Ozarks accent and sad cowboy lovers. Kim Stanley had made the role famous on Broadway, but Monroe embraced the character as her own. She connected to Cherie, clawing her way out of tawdry surroundings, tattered but clinging to threads of raw hope. She played Cherie with all her heart—essentially it was the story of her life.

The critics went wild. "Hold onto your chairs, everybody," wrote The New York Times' Blakey Crowther, "and get ready for a rattling surprise. Marilyn Monroe has finally proved herself in Bus Stop."

"Speaking of artists," Arthur Knight wrote in the Saturday Review, "we have a very real one right in our midst...for miss Monroe has accomplished what is unquestionably the most difficult feat for any film personality. She has submerged herself so completely in the role that one searches in vain for glimpses of the former calendar girl."

Just weeks after Bus Stop's glowing reviews, Darryl Zanuck fled to Europe and abandoned Fox. RKO was weeks away from collapse, and even Paramount teetered on the verge of bankruptcy. By 1957, the majority of American films were produced independently. Stars like Frank Sinatra and Gary Cooper followed Monroe's lead, forming their own small companies and buying cutting-edge scripts. It was undeniable—the "million-dollar mediocrity" was finally crumbling, and the Big Five tycoons were on their way out.

Years ahead of her time, and dead at the age of 36 in 1962, Monroe wouldn't live to see the changes she made possible. But her reach went far beyond the machinations of Hollywood and shifted the way women around the world viewed themselves: Bra-less and never in girdles, Monroe didn't apologize for her raw sensuality and frankly admitted to posing nude in the past; she'd been a penniless starlet and whose business was it anyway? At the same time, she wasn't afraid to appear "unsexy." She loved being photographed in grimy boas and ripped fishnets, or puffy-eyed and makeup free, hair tangled from hours of fitful sleep. Monroe wanted to express herself, no matter the risk.

In 2017 we need Monroe more than ever. Sixty-two years after her victory, women comprise only 24 percent of producers, 13 percent of writers, 7 percent of directors, and 5 percent of cinematographers. The gender pay gap is still massive, and male leads are paired with actresses twenty years younger. But women in Hollywood's are rebelling. Like Monroe, they are sick of being typecast and objectified, underpaid and underestimated, devalued, ignored, and ultimately spit out. From Jennifer Lawrence to Emma Watson, they are following her footsteps, speaking out against the status quo and demanding what's theirs.

Perhaps Reese Witherspoon resembles Monroe the most—a brainy blonde and avid reader, an actress turned producer with a fondness for adapting quality novels to film.

Perhaps Reese Witherspoon resembles Monroe the most—a brainy blonde and avid reader, an actress turned producer with a fondness for adapting quality novels to film. Like Monroe, she's endured Hollywood's sexism. And like Monroe, she channeled frustration into action. Desperate to get "different, dynamic women on film," she founded production company Pacific Standard. With a focus on complex female characters, she's adapted Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl, Cheryl Strayed's Wild, and most recently Liane Moriarty's Big Little Lies. Her devotion to telling women's stories is obvious: "I'm passionate because things need to change…I feel like I constantly see women of incredible talent playing wives and girlfriends in thankless parts, I just had enough," she told Vanity Fair. "We need to see these things because we as human beings learn from art and what can you do if you never see it reflected?"

Her predecessor would be proud.

Elizabeth Winder is the author of Marilyn in Manhattan and Pain, Parties, Work: Sylvia Plath in New York. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.