These Women Own Sports

Seriously, though. As interest in the WNBA, NSWL, and other female leagues grows, so too, do the number of women investing in pro sports teams.

For Renee Montgomery, it seemed obvious: 2020 would be a banner year. The superstar basketball player—who had been playing with the Atlanta Dream since 2018—was finding her groove on the team and commentators predicted the Dream would make it to the championship.

Then came a pandemic, an overdue racial reckoning, and personal transformation. Montgomery decided to sit out that season, heartbroken over the global health crisis and committed to doing what she could to boost the Black Lives Matter movement. But even from her perch on the sidelines, the unfolding drama was unmissable.

At the time, Republican Senator Kelly Loeffler was a co-owner of the Dream. While protests over the murder of George Floyd were raging nationwide, Loeffler was criticizing the WNBA’s public emphasis on social justice. Pressure mounted on Loeffler to sell her ownership stake as her team threw its muscle behind Loeffler’s opponent in the upcoming election. Raphael Warnock went on to win in a run-off contest. A few weeks later, Montgomery announced that she was part of a three-member investor group that the league had approved to replace Loeffler at the helm of the organization. With the move, Montgomery became the first WNBA alum both to co-own a team and to serve as an executive for a franchise.

Ownership had until that point not been on Montgomery’s radar. Her wife had encouraged her. How better to spend her retirement than immersed in the game? Plus, Montgomery could see the trendlines that were just starting to take off: The field of women’s sports was attracting new attention. This wouldn’t be some philanthropic second act. This was good business. “What made me start thinking about it was, ‘Wouldn’t it be really dope if we had somebody in the ownership seat that thought like us?’” Montgomery remembers now. She went for it.

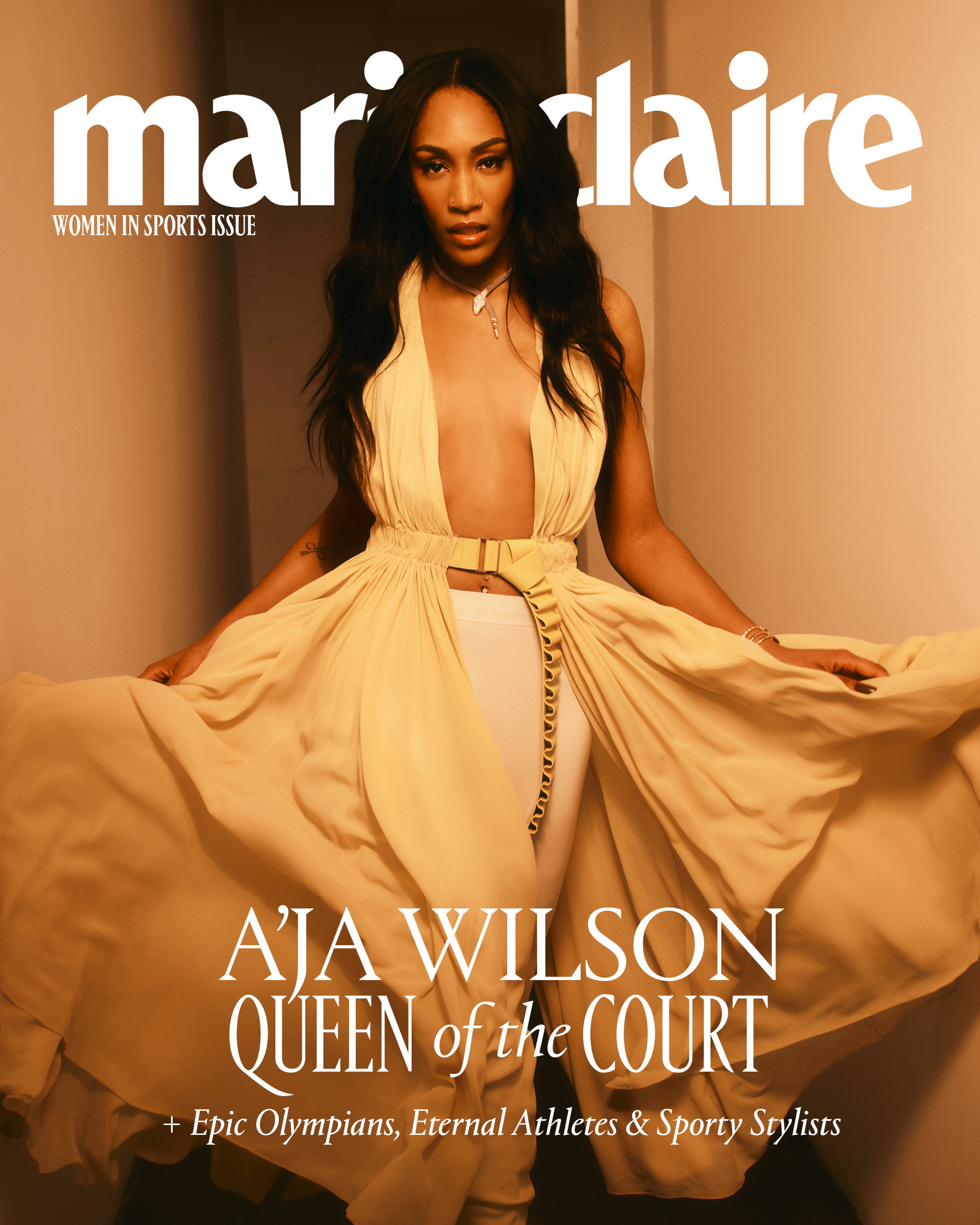

Montgomery, who will tell her story in a new Roku Originals documentary titled A Radical Act: Renee Montgomery, knows what you likely do too: That interest in women’s sports has exploded since that summer. In 2023, Nielsen crunched the viewership numbers and characterized the growth in audience for women’s sports as “meteoric.” On the heels of blockbuster events like the Women’s World Cup in 2023 and the NCAA women’s tournament in 2024, Deloitte forecasted for the first time ever that women’s sports would surpass one billion dollars in revenue—a 300 percent increase compared to a similar evaluation in 2021. There have been women’s sports stars—and rivalries—before, but there is no question that the WNBA has minted a new class of bonafide standouts this season, with Caitlin Clark on the Indiana Fever and Angel Reese on the Chicago Sky driving not just fandom, but merch and ticket sales and obsessive online speculation. In June, ESPN reported that a rematch between the two netted 2.3 million viewers. It was a reprisal of their nail-biter faceoff in the quarter finals of the NCAA women’s tournament, and it became the most watched women’s professional basketball game in over two decades.

What has been less publicized however is the phenomenon that Montgomery herself exemplifies: Across leagues and from a diverse range of backgrounds, a growing number of women have taken their investment in the future of these leagues and made it literal. From soccer to basketball to football, women are pouring dollars into existing teams and founding new ones—not just to be cheerleaders to a nice cause, but to cash in on a big-and-getting-bigger business. Women are not necessarily more progressive owners (as Loeffler’s example proves), but the kinds of women who have flocked to ownership of late do seem to bring more than “representation” to their stadium suites.

Conscious of unequal training facilities, salaries, marketing spend, and media rights, new stakeholders are helping to drive the revolution in women’s sports that the rest of us are watching on TV and TikTok. That narrative? Well, these women are owning it.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Of course no one had to explain to Carolyn Tisch Blodgett what she might stand to gain from an investment in a promising sports franchise. In 1991, her grandfather Bob Tisch bought 50 percent of the New York Giants. She was six and grew up with the team, calling it the “anchoring point” of her childhood. The stadium was the site of innumerable memories, and the investment turned out to be a brilliant one. Forbes now values the team at 6.8 billion dollars. After college, Tisch Blodgett went to work in marketing, but kept a focus on athleticism and sports. She worked at Peloton. She got more involved with the Giants. She made it her job to see opportunities and to chase them. “I realized quickly that the world of sports was changing, and we had a chance to either watch it change around us or lean in and be part of that change,” she explains.

Jeanie Buss, the controlling owner of the Lakers and the co-owner and promoter of U.S. women’s professional wrestling league Women Of Wrestling, could see the shift too. Having inherited her love of sports from her father, Jerry Buss, who bought the Lakers in 1979, she has lived through several eras of increased awareness in women’s sports and then watched it drop off.

Buss vividly remembers when Ann Meyers became the first woman to sign a contract with an NBA team, scoring a $50,000 deal with the Indiana Pacers the same year Buss’s father acquired the Lakers. “She was my basketball idol,” Buss says. “It was a PR stunt, but she was being talked about.” Later, when the WNBA was getting off the ground, Buss and her father were some of the first NBA owners to put their hands up for franchise ownership in the new league. Buss has been a fan and booster of women’s sports since she watched Billie Jean King triumph in the infamous Battle of the Sexes tennis match in 1973, but she still chafes at the casual sexism she has endured as a leader and executive in men’s sports. After the Busses moved to launch the Sparks as the sister team to the Lakers, David Stern, the NBA commissioner who helped mastermind the WNBA, assumed Buss would run it. Buss’s father corrected him. “No, David, I’m grooming her to run the Lakers,” he told Stern.

Between the Lakers and Women Of Wrestling, Buss has more than one full-time job, but other women owners do reach out to her to talk shop, and it’s given her a sense of camaraderie she didn’t quite know she was missing. “It’s nice to talk to women who understand revenue streams, how to sell sponsors, how important it is to have the right venue,” she says. “It’s women making these decisions.” That was not the case when she got her start. Buss has followed with particular interest the valuations and sales of women’s soccer teams, noting that recent transactions prove “investors are getting paid” and that perhaps having women at the helm helps.

“My dad said that women’s sports would take off when women were the ones buying the tickets, when women were the ones investing in the teams,” Buss says now. “And that to me is what has happened. You’re seeing women invest in opportunities in sports.”

To capitalize on them, Tisch Blodgett pitched a venture fund to her mother and uncles devoted to the intersection of sports and culture. With their backing, she founded Next 3 and zeroed in onwomen’s sports. She theorized that after three decades, it was obvious that her grandfather’s bet had been a good one. Three decades from now, she wanted to be able to tout a similar return. She listened. She looked around. And in November 2023, Gotham FC—the National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) team based out of New York and New Jersey—announced that Tisch Blodgett had come on as an owner and strategic investor in the team. About 72 hours later, it won the league championship.

Eight months after that, Tisch Blodgett insists her team—and the league as a whole—is just getting started. When she made the case to her family that she wanted to spend time and resources on Gotham, she identified three areas of potential growth: first, media deals to make games more accessible and visible to fans, second, investment on the part of not just owners, but brands with marketing dollars to allocate, and third—and Tisch Blodgett knows this sounds ridiculous given the past several months—cultural conversation and impact. She reasoned that if the status quo moved just “a few percentage points” in a favorable direction across all three vectors, the investment would prove worthwhile.

That’s a point that Clara Wu Tsai echoes. In 2019, Wu Tsai and her husband, Joe Tsai, bought the New York Liberty. The team was performing well, but then-owner James Dolan had overseen its move from Madison Square Garden to the Westchester County Center, where a grand total of 2,500 people could watch the team on the court. The Tsais—who also own the Nets—knew that the Liberty had been underinvested in. “It was pretty much a distressed asset,” Wu Tsai says. “So we thought, ‘Okay, let’s take a look at this.’ And instantly, we saw the business potential.” Wu Tsai especially liked “the fundamentals,” as she terms them: great players, the largest media market in the world in the Liberty’s hometown of New York, and a built-in fanbase.

With the ink dried, Wu Tsai and her husband—whose wealth was amassed from his role at the Chinese tech superfirm Alibaba—moved the Liberty to the Barclays Center, where the Nets play. The couple hired a performance staff, including multiple trainers and a nutritionist. Memorably, the Tsais decided to incur a $500,000 fine in 2021 so that the team could use private jets rather than travel commercial, as the league then mandated that all teams do. The gambit forced the WNBA to allow franchises to charter flights for select games during the regular season and championship, bringing the league one step closer to the conditions and amenities that NBA teams have come to expect.

Later, when it came time to build out the roster, Wu Tsai took an active role and followed Breanna Stewart to Istanbul to convince her to sign during the off-season. It’s impossible to know whether her husband would have been as successful in his own full-court press because Wu Tsai handled the final pitch herself—woman to woman. Within a matter of weeks, Wu Tsai had nabbed not just Stewart, but Courtney Vandersloot and Jonquel Jones. The bets paid off. The Liberty made the playoffs in 2021 and 2022. Its home games now draw a rabid crowd, with GQ declaring the scene at Barclays when the Liberty are on the court “the best party in NYC right now.”

With that momentum, Wu Tsai helped execute a media rights deal this spring that has made Liberty games free to watch in this season on local television. WNYW FOX5 is broadcasting the games throughout 2024 on FOX5 and My9, reaching a total of 7.5 million households. A party is nice; ratings—and the ad buys that come with them—are nicer.

Wu Tsai believes as Tisch Blodgett does that we’re just at the beginning of the movement to mainstream women’s sports, with millions of untapped fans and billions of untapped dollars out there for the taking. It doesn’t surprise her that it’s women who have rushed in to make the most of that potential. “We see opportunities more clearly,” Wu Tsai says. It occurs to her that perhaps women see challenges more clearly, too. “The WNBA is like the ultimate underdog league, isn't it? We deal with misogyny, racism, homophobia—it’s all there. And so I think it’s also that we tend to take that on.”

To those who doubt her commitment, Wu Tsai can only insist that she and her husband are “here for the long haul.” With a laugh, she notes that she’s in good company. She’s particularly aware that players themselves—Montgomery included—have started to see ownership as a viable retirement plan, “and they actually have the best perspective of anyone,” she points out.

It’s a sisterhood that includes Naomi Osaka, who in 2021 invested in the NWSL’s North Carolina Courage, WNBA champion Sue Bird, who joined Tisch Blodgett as an investor in Gotham in 2022, Angel Reese, who within weeks of the WNBA draft became a part-owner of the USL’s DC Power (along with other personalities like the actor Crystal Renee Hayslett), and of course at least a dozen former athletes like Serena Williams and Lindsey Vonn who are part of the ownership group that controls the NWSL’s Angel City.

“I think we’re in an age now where athletes are more aware that they are a walking business,” says Jemele Hill, a contributing writer for the Atlantic and a sports commentator, of the cascade of women players who’ve moved into ownership. She sees an exhaustion among female players and executives alike, who are “tired of being told they need to just be happy to be here.” The movement that has driven a rise in attention—and dollars—for women’s sports is happening “because women refuse to be told no, and they refuse to be placated and patronized,” she says.

“I do think there are issues that women intrinsically understand that men don’t, not because maybe they don’t want to, but mostly because it’s not their lived experience,” Hill continues. “And so while I can’t say this as a necessarily a blanket statement because you do have women who just want to emulate how the patriarchy works, I do think there is a different level of understanding for women who are involved in ownership in women’s sports because women understand innately what it’s like to have to fight for respect on the job, to have to fight tooth and nail for basically everything.”

Over and over, the idea of respect is one that the owners I speak to come back to. How can players in the WNBA and NWSL command the same respect as their male peers? What does it mean to invest in their game—with better facilities, better pay, and better opportunity? If previous—and more male—owners were ruminating on these issues, it wasn’t evident in the suburban, cast-off stadiums that women were made to play in or the shoddy equipment that went viral after players and couches called out the gaping disparities between the men’s and women’s NCAA basketball tournaments in 2021.

The prospect of addressing those inequities and turning a profit is part of what’s drawing even less likely owners to the executive pool. The actor Sophia Bush has always been an avid sports fan, but it was considering the patterns of impact investing that made her want to invest in Angel City. “We know that if you give money to or invest money in men in so many places around the world, men will spend upwards of 90 percent of that money on themselves,” she says. “And if you invest in women, women tend to reinvest nearly 90 percent of that investment in their community.” She didn’t hesitate, despite the fact that people told her it was a mistake to write a check. “And now there’s a bunch of people who wish they’d gotten in when I did,” Bush says, laughing. Meena Harris, an author and the CEO of Phenomenal Media, will soon announce her own stake in a women’s sports team and has made it a point of her career to see promise where others do not. “It was just a no brainer to me in terms of where I want to be.” she says.

Bush is proud to boost her team and women’s sports in particular, but no one owner can fix all the problems that plague women’s sports and continue to hold it back. “You see the greatest awareness and attendance in the WNBA that we’ve ever seen before,” she says. “The WNBA is absolutely crushing it, and women in that league are still having to educate men that they don't have the same kinds of deals that the men have.” Bush would like to see women command a percentage of revenue, as men do in the NBA, and be able to participate in profits that their talent and their likeness earn for others.

Tisch Blodgett has a long list of her own priorities. She is the first to volunteer that if the game is to be changed, risks must be taken. “It was a big bet,” she reminds me. And so while the success so far feels validating, she sees what must come next. Attention is vital. Increased coverage is great, although women’s sports still get far less of it than men’s sports do. But, she points out, “buzz doesn’t translate into revenue immediately. And so our challenge is to say, ‘Great, I’m so happy everyone is talking about this. But we need to get butts in seats. We need to sign sponsors.’ We have 13 home games. We just added a bunch of summer tournaments. We have a 25,000-person stadium.” Tisch Blodgett sees this moment as the first stage “of a transformational moment in sports.” When she talks to brands, she frames the chance she is offering them like that—get in on the ground floor, be part of this. Some refer her to their foundations. But others get it, and have poured their dollars into Gotham and the league.

As much as the owners themselves, Bush and others credit women like Andrea Brimmer, the chief marketing and public relations officer at Ally Financial, for helping to even the literal playing field. Brimmer, who is a former Division 1 athlete, wasn’t looking to make a donation when she pledged that Ally would allocate an equal spend on advertising between men’s and women’s sports within five years in 2022. She was looking at the numbers. Already, she tells me, the return has been extraordinary. Brand awareness and sentiment are up. Ally is one of four banking brands to have grown its trust over the past year. Brand value grew 32 percent, the highest jump in the last five years. “And while I can’t say a hundred percent of it is attributable to women’s sports,” she adds, “I would tell you that a big part of it is and that 65 percent of everybody who came to our storefront last year was female.”

Brimmer is proud of the record, but she has to admit it’s not just the math that moves her. A few years ago, Ally partnered with CBS to put the NWSL championship game in primetime. The game was held in DC, and it was almost completely sold out. The year before, Brimmer had stood in a half-filled stadium while top-tier players competed at noon. The contrast made her tear up. “I’m thinking, ‘No little girl is ever going to have to think they’re not worthy of primetime ever again,’” she says. “It was very emotional for me. You realize that the bet was right.”

Tisch Blodgett invested in Gotham with a business plan, but she concedes that there is a lens through which she sees its potential that a different owner might not have. Just as she grew up with the Giants, her own children are growing up with Gotham—two sons and a daughter. She has watched her sons become “as passionate about this women’s team as they are about a men’s football team,” which bodes well for the future of the sport. And she has watched her daughter, “who loves football and goes to all the Giants games, get to have that experience of seeing her own role models on the field.”

Tisch Blodgett credits her fellow women owners—the group behind Angel City, Michele Kang who owns the Washington Spirit, Jennifer Epstein, who is bringing an expansion team to Boston, Laura Ricketts, who led a 60 million dollar deal to take ownership of the Chicago Red Stars, and others—for understanding that the solution to marketing women’s sports is not just to “shrink it and pink it,” a tactic that generations of men have used to appeal to female consumers. It’s to design better facilities, push for better deals, and appeal to a new generation of fans eager for live events, the camaraderie of sports, and the drama that true, top-level talent bring to the game.

Are women better than men at monetizing women’s sports? In a decade or two, the data will decide. But for now, Montgomery doesn’t need to consult the metrics. Like the smartest plays, this one is simple, she says. “I don’t think it should be controversial to say that a woman in a leadership position in a women’s league just makes sense.”

Mattie Kahn is a writer who lives in New York. She covers politics, style, culture, and dangerous women. As far as she's concerned, candidates come and go, but the Oxford comma is forever.

-

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"Here's what to know about the Max series's breakout star, who just so happens to come from TV royalty.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an Apology

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an ApologyThe season finale of the smash Max series proved that the most unlikable character on TV may just be the hero we all need.

By Jessica Toomer Published

-

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 Million

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 MillionHulu's answer to 'The Traitors' is here.

By Quinci LeGardye Published