Self-Doubt and Sacrifices—Dorsey’s Meg Strachan Gets Candid About Launching Her Jewelry Company

\201cHave we made it? From the outside, perhaps. Internally, we are working really hard to make it every single day.\201d

The Cost of Starting Your Own Business talks to founders to get an honest look at what it really takes to create a company. Not just the financial, but the personal and emotional costs, too.

Being a self-starter is in Meg Strachan’s blood. In addition to her father, almost every member of Strachan’s extended family runs their own business. “I grew up around a lot of people who own companies, who worked every single Saturday,” she says. “I had a pretty informed idea of what it takes—I’ve seen it all.” It seemed only natural she’d launch a venture of her own, and in 2019, she did: founding Dorsey, a lab-grown jewelry brand offering contemporary yet vintage-inspired heirlooms.

“I was at this little Parisian market where this older French woman was selling vintage jewelry,” she says. “I picked up a pair of earrings with a 1920s deco feel. They reminded me so much of my grandmother, Dorsey, who collected costume and fine jewelry. She wore her pieces in a way that I had never seen on anyone else. That was how I decided to start Dorsey: with this love for jewelry and connection to my grandmother.”

Plus, Strachan had found her niche: "Lab-grown was, and still is, a disruptive category." Manufactured entirely by humans in controlled laboratory environments, synthetic stones are marginally less expensive than mined diamonds. Strachan recognized the fringe industry's potential—and profitability—and wanted in. "It's giving the diamond market a run for its money and will continue to do so,” she says. “Lab-grown will be the dominant stones one day."

But despite Dorsey feeling somewhat destined to be, and Strachan's insight into the back end of business-building, the journey has been far from easy. On a Zoom call from her home in Los Angeles, the founder reveals the candid details of getting her brand off the ground, from all-nighters to self-worth spirals—and why making her first million didn’t feel like she thought it would.

I held two full-time roles for the first two years of the business. I did my day job, and then at night, on weekends, and in the very early morning hours, I was building Dorsey. For a long time, I couldn't afford to hire an employee, so I did everything myself—the graphic design, everything for the website, all the emails; all the packing, shipping, and customer service. I shipped over a million dollars in orders by myself from my house. Dorsey was all my free time.

I went out to investors in 2019 to raise money. I got my foot in the door and, naively, thought I would be able to fundraise for Dorsey because of my previous career successes at other companies [as the Vice President of Growth for the Girlfriend Collective and the Chief Marketing Officer for Anine Bing]. But I couldn't raise a dollar of funding. Literally—not a dollar. Nobody would invest, so I had to move forward with the business by bootstrapping it.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

I started the company with between $600 and $1,000 [of my own money]. I would take the money from my paychecks and put it directly into [Dorsey]. I’m in a double-income household. At the time, I didn't own my house, so I was paying rent. I had an 18-month-old daughter, so I was paying for babysitters and nannies.

If you raise money, it's a totally different experience because you can take some type of salary and have capital for the business to run off of. But starting a business by putting your money into it each month is a very different way to start and run a company. You're personally feeling the exposure every month. It's a constant reminder of the financial risk that you're taking.

I'll never forget: I was in a meeting with the partner of a very prominent venture fund. He looked at me, and his exact words were, ‘You have the exact pedigree of someone we would invest into. [But] we don't really know about the lab-grown market. We asked a couple of girls around the office who like jewelry, and they’re unfamiliar.’ That fund turned me down.

All of [those investor meetings] were so devastating. You get dressed up. You hype yourself up and work with whatever self-esteem you've manufactured for that hour or two meeting. You’re ready to pitch, you have your deck ready. And then they reject you. That was the main emotion I had for the first two years of Dorsey: rejection.

Starting and running a company takes an unspoken toll on your life. I call it a tab that comes due, and the tax on it is very high. There are a lot of personal sacrifices. You have to be ruthless with your priorities. You miss a lot of things—that's the truth. I missed the first four years of my daughter's life. I missed all of preschool. Even if I was physically there, I wasn't mentally there. I basically put my head down, ran Dorsey for the last four years, and when I looked up, my daughter was five.

I've had to reconcile with myself that, okay, I built this business, and it's had an amazing trajectory. But as a parent, I missed some pretty critical years. I did my absolute best and was there as much as I could be. And it was necessary [for Dorsey]. But was it worth it? I went through a grieving process about that because I'll never get that time back with her.

For me, [jewelry] really comes to life in how it's worn and who it's worn by—the zhuzh of a sleeve, the way the pieces are stacked, or the actual person you're shooting on. So, our best investment was finding the budget for great models and photographers. It was a very big stretch, financially—the model fees, agency fees—but it was my first investment.

I had this conversation with my dad a few years ago. He called and caught me in a moment of feeling scared. I said, ‘The business is doing well, but I'm afraid, Dad. This is getting bigger, and the financial stuff is building.’ He asked me what my worst-case scenario was and it was that I would fail. ‘Can you handle that?’ he asked. I thought about it for a minute and said yes. ‘Then you don't have anything to be afraid of,’ he told me. ‘If you can get comfortable with failing, which may happen, then my advice is to go full steam ahead.’ I realized that if you can accept failure to some degree, you’re unleashed from its shackles, otherwise it will stop you in your tracks and hinder your growth.

[Running a business] is an incredibly lonely and isolating experience. The mental piece is so much bigger than people talk about. One of the hardest parts of starting and staying in a company is the mental fitness you have to have in order to keep yourself moving. There is only you who's motivating yourself. You’re up against yourself day after day for years—that's something that you have to commit to getting really good at.

Some of the darkest moments of my life have been running this company. A lot of self-worth things came up—a lot of anxiety, depression, and self-doubt. What's weird is that it was unrelated to the company and our success. We've had an incredible trajectory. We did 600 percent year-over-year growth in 2022, and 100 percent last year. We’ve had a journey that I could never have dreamed of.

It's counterintuitive that you would have some of the hardest, truly most difficult moments of your life, while it looks to the outside world that everything is great. As a founder, you're on a journey that's very integrated with your business, but also separate and apart from it. Those can be mutually exclusive, very layered experiences.

Being able to pay for health insurance for [my employees] was big. The small and seemingly mundane things are the most exciting, like customers who buy from us and come back and buy again. But the truth is, I have never felt that we've made it. I used to think it would be when we hit $100,000 in sales, but the goalpost is always moving. It moved to five million. Then 10. And so on. As a company, I don't look at us and think we've made it—and I don't think I'll ever feel that way. I have worked for many companies that are no longer in business; I know too well how quickly the tides can shift. So, have we made it? From the outside, perhaps. Internally, we are working really hard to make it every single day.

When you combine the financial risk with how you're feeling mentally and all the rejections, the thing that keeps you going—and I can't minimize it—is how your product is received out in the world. You get fueled by people who actually love your product. The people who send us emails about how much they love our products. When I was packing and shipping orders literally in the middle of the night for all of our holiday sales in 2020, that’s what kept me going. We're here because of our clients and our customers. That’s a very easy thing to forget at three o'clock in the morning when you're overtired and financially scared.

My dad said that when you're an entrepreneur, you walk this plank carrying an invisible weight on your shoulders. In the beginning, it feels like a massive weight and only gets bigger and bigger and bigger. Eventually, you learn to put blinders on and do it despite how you feel. You're running on empty, but you just keep going. All of a sudden you're carrying [that weight], but you feel it a lot less. One day, you realize that you've built those muscles and it doesn’t feel as heavy anymore.

Emma is the fashion features editor at Marie Claire, where she explores the intersection of style and human interest storytelling. She covers viral styling hacks and zeitgeist-y trends—like TikTok's "Olsen Tuck" and Substack's "Shirt Sandwiches"—and has written hundreds of runway-researched trend reports about the ready-to-wear silhouettes, shoes, bags, colors, and coats to shop for each season. Above all, Emma enjoys connecting with real people to yap about fashion, from picking an indie designer's brain to speaking with athlete stylists, entertainers, artists, politicians, chefs, and C-suite executives about finding a personal style as you age or reconnecting with your clothes postpartum.

Emma previously wrote for The Zoe Report, Editorialist, Elite Daily, Bustle, and Mission Magazine. She studied Fashion Studies and New Media at Fordham University Lincoln Center and launched her own magazine, Childs Play Magazine, in 2015 as a creative pastime. When Emma isn't waxing poetic about niche fashion discourse on the internet, you'll find her stalking eBay for designer vintage, reading literary fiction on her Kindle, doing hot yoga, and "psspsspssp-ing" at bodega cats.

-

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"

'The Pitt' Star Taylor Dearden Says She Sees Her and Dr. Mel's Neurodivergence as "a Superpower"Here's what to know about the Max series's breakout star, who just so happens to come from TV royalty.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an Apology

We Owe Trinity Santos From 'The Pitt' an ApologyThe season finale of the smash Max series proved that the most unlikable character on TV may just be the hero we all need.

By Jessica Toomer Published

-

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 Million

Your Guide to the Cast of 'Got to Get Out,' Which Pits Reality TV Alums Against Each Other for a Chance at $1 MillionHulu's answer to 'The Traitors' is here.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Ella Emhoff Never Intended to Be an It Girl—All She Wants Is to Knit

Ella Emhoff Never Intended to Be an It Girl—All She Wants Is to KnitThe second stepdaughter and former fashion model opens up about her true passions: art, knitting, and community.

By Emma Childs Published

-

What It Takes to Bootstrap Your Own Art Gallery in New York City

What It Takes to Bootstrap Your Own Art Gallery in New York CityIt took Lin Tyrpien more than a decade to find her calling. When she realized she wanted to run her own creative space, the real work began.

By Jenny Hollander Published

-

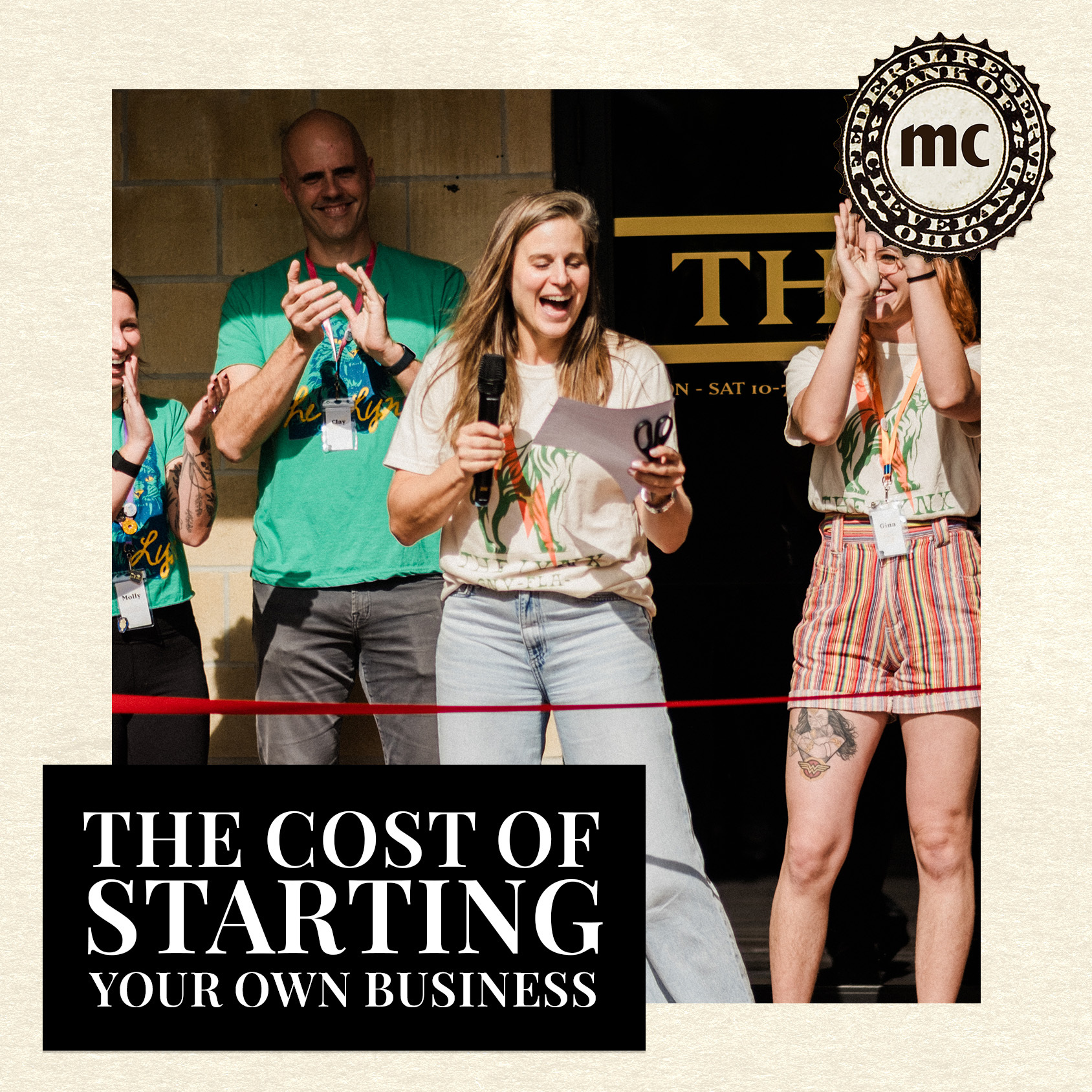

Lauren Groff on What It's Like to Launch a Bookstore in the Land of Book Bans

Lauren Groff on What It's Like to Launch a Bookstore in the Land of Book BansThe Lynx opened in Gainsville, Florida as a foil to the state's legislation in support of censorship.

By Marie Claire Editors Published

-

For Deepica Mutyala, Entrepreneurship Is Worth the Sacrifice

For Deepica Mutyala, Entrepreneurship Is Worth the SacrificeThe Live Tinted founder talks having it all—but not all at once.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published