What It Takes to Bootstrap Your Own Art Gallery in New York City

It took Lin Tyrpien more than a decade to find her calling. When she realized she wanted to run her own creative space, the real work began.

The Cost of Starting Your Own Business talks to founders to get an honest look at what it really takes to create a company. Not just the financial, but the personal and emotional costs, too.

For over a decade, Lin Tyrpien sought to identify her professional North Star. From creative roles at Ralph Lauren and Christie's to managing a guesthouse in Bali and learning to weld in Arizona, nothing quite fit—until she was recruited to New York's Chase Contemporary gallery in February 2023. As it turned out, running a gallery was Tyrpien's calling. "I had been searching for that 'aha' moment for 16 years," she says.

Exhilarated by the realization, Tyrpien decided to pursue a space of her own. In May 2024, she and her wife Magdalena opened Lyle Gallery, a name they came up with after two glasses of wine as they prepared to launch. Eclectic, wide-ranging, and wholly original, the Chinatown gallery seeks to spotlight the artists and businesses often boxed out of the mainstream art world. "We have zero interest in hearing from the same privileged groups that have dominated the arts scene for years," Tyrpien says. "At the end of the day, we want this to be an inclusive and beloved space."

Like their artists, the Tyrpiens come from nontraditional backgrounds for New York City's art scene. Both grew up working-class, Lin in rural Pennsylvania and Magdalena in Poland. They bootstrapped Lyle using their own funds, divvying up the nuts and bolts of gallery ownership: Magdalena handles budgets, project management, and contracts, while Lin oversees their artists, marketing, and exhibitions.

In the run-up to their debut show, which features artists' metal works—more on that in a moment—Lin emailed with Marie Claire about their leap into the gallery business.

I started thinking about this about a year ago, just a few months into working at a gallery in SoHo. Once I was in that world, I discovered that, yes, OK, I found the thing I want to do, so now I am going to learn as much as I can and open my own version of this. At first we were just going to do pop-up exhibitions; it seemed like an easier barrier to entry. Then something shifted, and almost unsaid, we started looking at permanent space options.

I went wide on locations, looking at spaces in Chelsea, Flatiron, Tribeca, SoHo, LES, Chinatown, Greenwich Village, even Midtown. I decided on the current location in Chinatown because it lends itself to experimentation, trying new things, failing, playing, and really discovering what Lyle Gallery is and who I am as a gallery owner. Traditional gallery hubs like Tribeca and Chelsea just felt too serious for me right now.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The inaugural show, which I started working on probably six months ago, opened in mid-May for NYCxDesign Week. It's a group show featuring works by artists working in metal (Jøna Maaryn out of Marfa Texas, Jamps Studio out of London, and “the city’s chainsmith," Johnny Valentine. out of NYC). Once I had my first artist on board, it really took shape from there and became real.

Magdalena worked really hard the last three years to facilitate a sale of the company she was working for. In doing that, we were able to put a small amount of money aside to get this up and running. I think it would have been unrealistic to try to do this without that sale happening first. Magdalena and I both come from working-class families, rather atypical to the backgrounds in which you typically see people opening galleries in this city. Magdalena immigrated from Poland as a child and I grew up in rural Pennsylvania. Odds were definitely stacked against us in that sense, but we’ve worked very hard in our professional careers to get to where we are now.

It’s a known fact that a lot of professionals in the art world come from a certain upbringing. But we’re proof that it doesn’t have to be the case, but it certainly doesn’t come without many obstacles and roadblocks. It’s been important to keep overheads like rent low. Right now, the salary from my part-time job covers the rent, which puts us in a good place. But we are definitely starting small and not jumping into a fancy space in a fancy neighborhood, and I am very happy with that.

Deadlines hit differently when it’s for your own company. It’s hard to justify a weekend or evening to relax and recharge when there is so much to get done. We’ve had to evaluate what in our life is propelling us forward and what is holding us back, and that can mean saying no more often. We have definitely outgrown our small one-bedroom apartment, but we made the decision to prioritize starting a business.

We were really scrappy about finding a location, contacting listings on Craigslist and Facebook, and walking around neighborhoods looking for “for rent by owner” signs and calling them up.

We ultimately found the space on Craigslist, which is just so fitting for who we are as people and as a couple. Aside from having good bones for a gallery space, we are most excited about this little secret room in the back in which we are scheming up an interesting use for the space that I can’t share yet.

Imposter syndrome (of course). Being OK with having uncomfortable conversations (I hate conflict). Learning to make quick decisions (I like to explore every option).

When I received the keys to the space, it was dark, cold, and pouring rain. I sat on the floor with the lights off, listening to the raindrops hitting the metal awning and watching the light come in from the street. I had imagined that moment for so long. I moved to NYC when I was 18 to attend design school at FIT and remember dreaming of that “one day” moment of having my own creative space. If I had planned ahead to bring a blanket and pillow, I definitely would have slept on the floor that night.

Visiting artists in their studios and having artists tell us that they are excited to work with us. Working towards something that is bigger than us, like bringing more voices from underrepresented communities and backgrounds to the front. The hidden lesbian poker room that we are building in the back of the gallery (I’ve said too much!).

“BE PUNK!” —Ella Fitch

“Walk into every room with the confidence of a mediocre white guy” —Magdalena Typrien

Jenny is the Digital Director at Marie Claire. A graduate of Leeds University, and a native of London, she moved to New York in 2012 to attend the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. She was the first intern at Bustle when it launched in 2013 and spent five years building out its news and politics department. In 2018 she joined Marie Claire, where she held the roles of Deputy Digital Editor and Director of Content Strategy before becoming Digital Director. Working closely with Marie Claire's exceptional editorial, audience, commercial, and e-commerce teams, Jenny oversees the brand's digital arm, with an emphasis on driving readership. When she isn't editing or knee-deep in Google Analytics, you can find Jenny writing about television, celebrities, her lifelong hate of umbrellas, or (most likely) her dog, Captain. In her spare time, she writes fiction: her first novel, the thriller EVERYONE WHO CAN FORGIVE ME IS DEAD, was published with Minotaur Books (UK) and Little, Brown (US) in February 2024 and became a USA Today bestseller. She has also written extensively about developmental coordination disorder, or dyspraxia, which she was diagnosed with when she was nine.

-

I'm Swapping My Winter Layers For J.Crew's Sale Linen Separates

I'm Swapping My Winter Layers For J.Crew's Sale Linen Separates25 under-$150 pieces to beat the summer heat in.

By Brooke Knappenberger Published

-

Jennifer Lawrence Just Prescribed the Doctor Bag Trend

Jennifer Lawrence Just Prescribed the Doctor Bag TrendInject this trend into my veins.

By Kelsey Stiegman Published

-

I’m Elevating My Summer Wardrobe With Aritzia’s New Collection

I’m Elevating My Summer Wardrobe With Aritzia’s New Collection25 breezy pieces I’m coveting for the season ahead.

By Lauren Tappan Published

-

Ella Emhoff Never Intended to Be an It Girl—All She Wants Is to Knit

Ella Emhoff Never Intended to Be an It Girl—All She Wants Is to KnitThe second stepdaughter and former fashion model opens up about her true passions: art, knitting, and community.

By Emma Childs Published

-

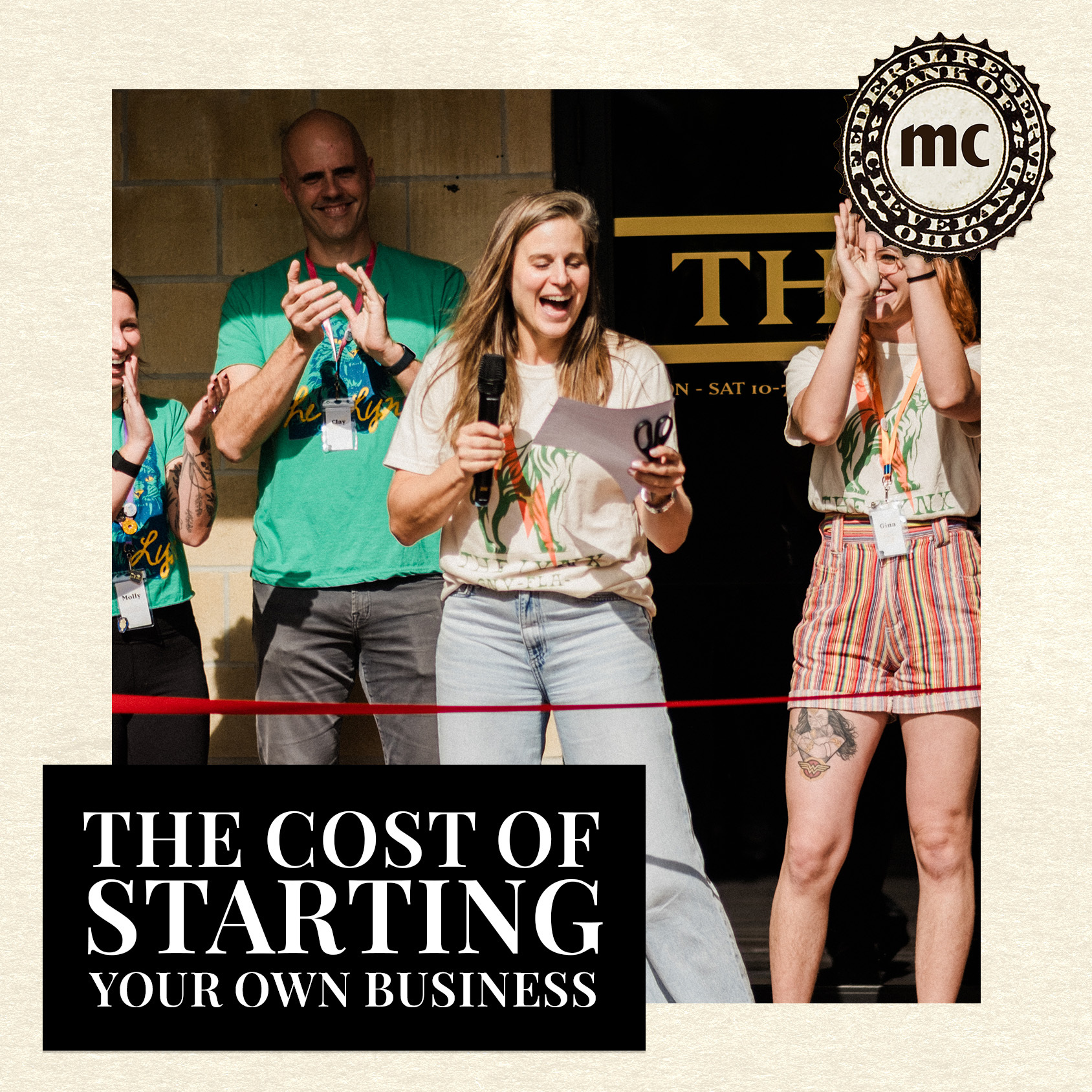

Lauren Groff on What It's Like to Launch a Bookstore in the Land of Book Bans

Lauren Groff on What It's Like to Launch a Bookstore in the Land of Book BansThe Lynx opened in Gainsville, Florida as a foil to the state's legislation in support of censorship.

By Marie Claire Editors Published

-

For Deepica Mutyala, Entrepreneurship Is Worth the Sacrifice

For Deepica Mutyala, Entrepreneurship Is Worth the SacrificeThe Live Tinted founder talks having it all—but not all at once.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

Self-Doubt and Sacrifices—Dorsey’s Meg Strachan Gets Candid About Launching Her Jewelry Company

Self-Doubt and Sacrifices—Dorsey’s Meg Strachan Gets Candid About Launching Her Jewelry Company\201cHave we made it? From the outside, perhaps. Internally, we are working really hard to make it every single day.\201d

By Emma Childs Last updated