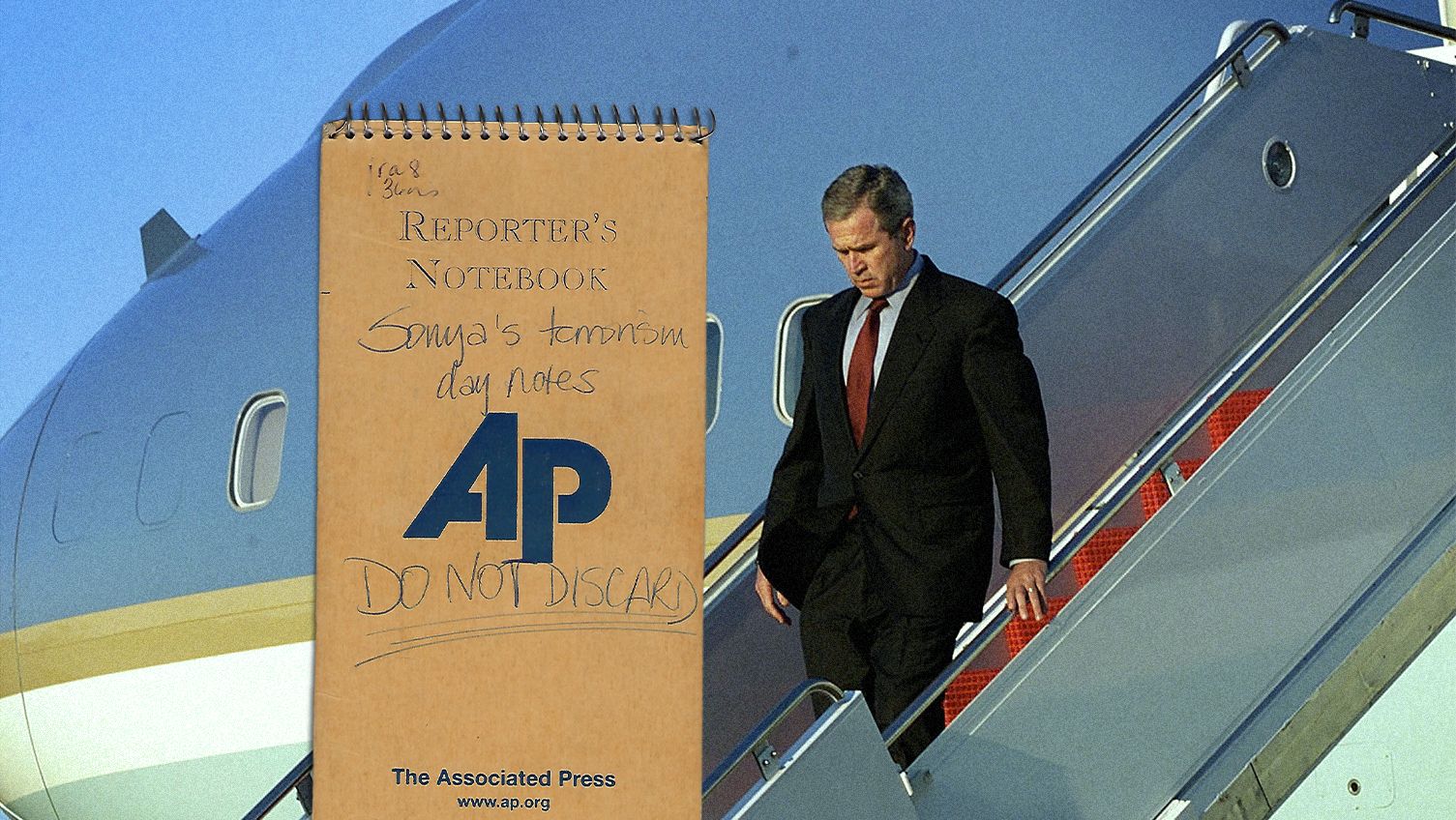

On 9/11, Sonya Ross Had to Balance Her Journalistic Duty and Personal Safety

The former AP White House reporter was one of five journalists selected for the "nuclear bunker pool" that traveled with President George W. Bush aboard Air Force One. Still, she had to remain cautious about what she reported from the sky.

Click here to read the complete "Reporting in Real Time" series

Twenty years ago, September 11, 2001 became—and will forever be—one of the biggest and most important news days in American history. As we remember the events that unfolded and honor the nearly 3,000 lives lost, Marie Claire asked five women journalists to reflect on covering the 9/11 attacks in real time and the lessons that can be learned today. Here, former AP White House reporter Sonya Ross describes what it was like flying on board Air Force One as one of five members of the "nuclear bunker pool"—a rare procedure in which a select few reporters travel with the president to safety in the event of a national emergency. (The size of the pool that typically traveled with the president is 13.) Get an inside look at Ross's day with President George W. Bush, below, then read the rest of the journalists' stories here.

One thing that sticks out in my memory every year is the night before 9/11. We were in Sarasota, Florida, [where President Bush was going to unveil an education initiative] and [instead of flying from D.C. on Tuesday morning], the president had gone down early because he was visiting with his brother. All of us who were traveling with him—the press, the agents, the White House aides—were hanging out in the little bar lounge of the hotel where we were all camped out having fun. We had been on this Sunday to Tuesday slog (it was considered "the nothing trip"), and I was in a very relaxed space.

The AP sent reporters on every presidential trip. We would go in pairs and we would swap each other out. (We would have one in the filing center, [an area the press pool sets up that has access to a TV and telephone lines to transmit stories], and one with the president at all times.) I was traveling with my colleague, Scott Lindlaw. After swapping Scott out, he went to the filing center and I went with the president in the motorcade (not literally in his car; we had our own van way back in the motorcade). By this time, it's a little after 8 a.m. and we're in the vans heading toward the school where the president was going to speak. Then Scott called me on my mobile and said, "Hey, there's a report out there that a plane hit the World Trade Center. That's all I know." It had come across the crawler on the TV in the filing center.

Sonya Ross

I called our desk in Washington and said, "Can I get some details about the plane that hit the World Trade Center?" And they said, "That's all we know. See what you can get out of the White House." There wasn't an official with us [in the van]. So once we got to the school, we were all trying to catch somebody who could tell us anything. Normally the presidential aides would linger a little bit hoping a reporter would catch up with them so they could share some special knowledge they had, but this particular day everybody left [us] like boom, bye, nobody's available. It went from a hypothetical [situation] where we are in the pool with the president just in case something happens to something happened and now we have to kick in.

When we got to the school, there were other members of the press corps who were not in the pool. So some of those reporters came out and met up with the pool like, "Hey, have they said anything? What's going on?" and we went, "We don't know." I'm still thinking small plane, weird tragedy and they said, "No, it was a jet." I said, "A jet hit the World Trade Center?" All of this happened in the short span of time between when the president arrived at the school and before he showed up in the classroom with the children.

When [White House Chief of Staff] Andy Card came into the room I was thinking, I've got to get to him to find out what's going on here. He came in from my left, but I wasn't close enough [to him] and I was saying to myself maybe when he finishes talking to the president, he'll come stand back here and I can say "Hey, what happened?" But when he went to the president, the president's face just drained of color. You could see the shock. I told Jay [Carney, White House correspondent for TIME magazine], "I think the president's face just confirmed what we want to know."

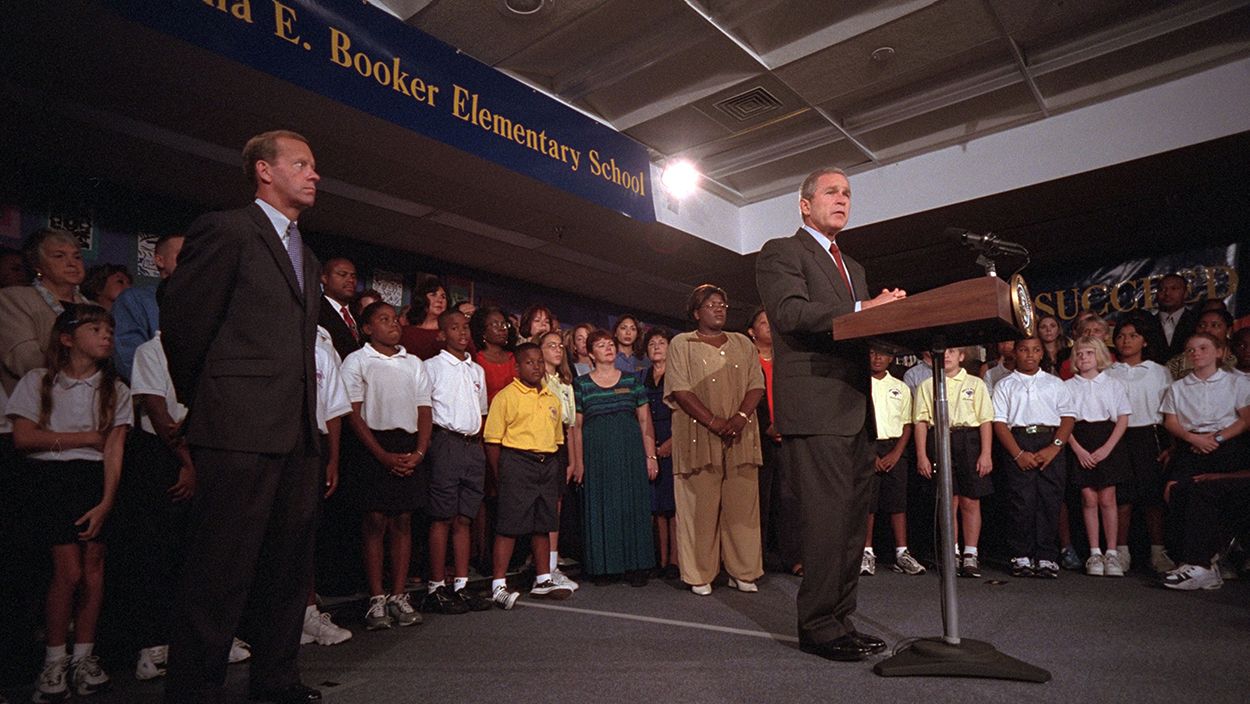

I want to say it was Dick Kyle from Bloomberg who shouted the question to the president, "Can you tell us what happened?" And [President Bush] cut him off. He said, "I'm about to speak about that. Let's not do that here." Then the White House [assistant press secretary] Gordon Johndroe and press secretary Ari Fleischer said to us, "Hey, the president is going make some remarks here at the school. As for the pool, we're leaving immediately. So be ready to leave at the end of his speech."

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

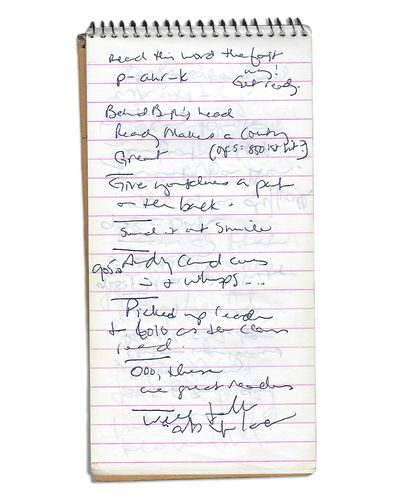

"When Andy Card came in and whispered to the president, there was a clock on the wall over the door he had entered through," explains Ross. "I looked at the clock, then checked my phone against my watch. My phone said 9:05 a.m. Any little detail like that that I could take down I did."

We were standing in the little cordoned off area of the auditorium where the president [made a speech]. I don't remember exactly his remarks, but I remember him using the word "terrorism." I wasn't ready for the word at all. Terrorism? It just seemed unreal because we hadn't had an attack that I could remember from foreign terrorists on U.S. soil like that. We had domestic terror in this country. As an African American growing up in the South, I had great awareness about the capacity for domestic terror from the Ku Klux Klan. But this was unfamiliar and scary and something there was a contingency plan for that people felt we'd never have to activate.

And there I was, caught up in the contingency plan.

Once [President Bush] made his speech [the White House press aides] said, "Let's roll, let's go." And we had to run from the auditorium to the motorcade. I'm running with my travel tote and my purse and my laptop bag. I still have my notebook [in my hands] while I'm trying to make a call. I was wearing denim slingbacks with a chunky heel and a closed-toe. I was thinking this sure would have been a good day to have on loafers or some other flat. The laptop was heavy because it had a CD-rom in it. I also had my full-size cassette recorder and a Palm Pilot.

Before heading to Air Force One, President Bush gives brief remarks at Emma E. Booker Elementary School in Sarasota, Florida, announcing the nation has been attacked.

Within minutes the motorcade was tearing away from Emma E. Booker Elementary School toward the airfield where we were going to take off. Sometimes when we turned corners, it seemed as if we were up on two wheels we were moving so fast. The cell towers on top [of the Twin Towers] were down, which meant cell phone access became very spotty and difficult, but during the ride from the school to the airfield, my sister, who's a minister, got through to me on my cellphone. She was asking, "Where are you? Are you safe?" And I said, "Of course, I'm safe. I'm with the president." I had not told my family I was traveling that day because travel was so common for me at that point that I didn't always get around to saying, "Oh, by the way, I'm going out of town."

My sister had seen a crawler on her TV in Atlanta that said a plane had hit the Pentagon. When we were talking, she knew that and I did not. She didn't tell me either because her primary concern with the little phone access we had was "Are you okay and where are you?" I told her, "Please do not tell mommy that I'm flying." My mother had a big fear of flying and the thought of me flying with [everything going on] just would have been too much for her.

So I asked my minister sister to lie to our mother until I could get situated back in D.C. She said "okay" and told me she loved me. And then she said, "Quick, we have to pray for traveling mercy." So I let her do her prayer for traveling mercy, which entailed praying for absolutely everybody on the plane, for God to put angels on the wings, to get us safely to our loved ones back in Washington, D.C.

I called our desk in Washington and asked for our bureau chief, Sandy Johnson. I told her we were at Air Force One and Ari Fleischer might give us a briefing on the plane and I planned to file [my report] from the plane if he did. And she said, "Okay. A plane has hit the Pentagon. I've got to go." And that's when I thought, how could we be going back to Washington if a plane hit the Pentagon? [The Secret Service and Air Force personnel] asked us to assemble our luggage [on the tarmac] for the bomb-sniffing dogs to review them. Then we scrambled up the steps onto the plane and took off. It felt like seconds. And [the plane] seemed to go just straight up into the air. Like a missile launch. We were moving so fast into the sky.

On the plane, I was waiting for Ari to come give us any details because we had to file a pool report and tell the folks outside of the little bubble we were in what was going on. At that time, we still had the full pool of about 12 or 13 people. Jay Carney was the magazine pool reporter [that day], and Judy Keen from USA Today was the newspaper pool reporter. So it was up to them to write the pool report and use a secure phone line on Air Force One to call it back to the White House to be distributed it to the rest of the press corps. I had the liberty of just taking my own notes and dictating things for my own employer.

The administration did what any administration would do in that moment: They shut down and said, "We don't have anything to tell you." Eventually, Ari did tell us the president had signed a [declaration of national emergency] authorizing the U.S. military to basically breach the chain of command due to the nature of this emergency. And he had made it retroactive back to the start of the terror attack. My question was, "Why is it retroactive?" The president was obviously at work and doing his job, so why does this need to be retroactive? I think Ari's answer amounted to "I don't know." They probably wouldn't give him an answer to share with us.

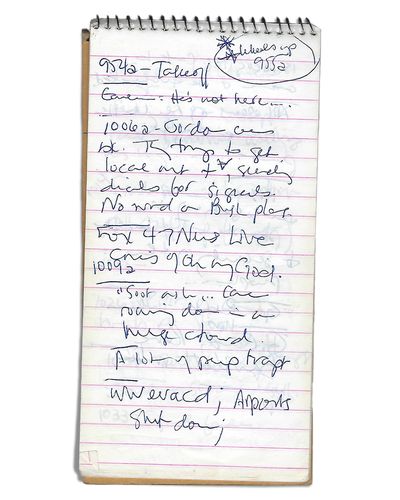

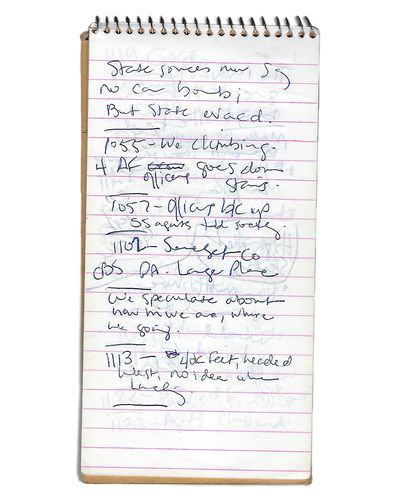

Ross jots down in her notebook "Wheels up 9:55 a.m.," referring to when Air Force One took off from Sarasota, Florida.

I was so busy trying to keep up with the timeline [myself and other reporters] were trying to put together that I had not noticed we were circling [in the air] for more than an hour. I'm thinking, we should be descending if we're really going back to Washington. We still had the same local affiliates on the TV, so we were obviously going nowhere real fast. The local affiliate coverage we were watching had a feed of the reporting on the ground in New York and all of a sudden I heard the reporters saying, "The towers are collapsing."

I looked up in time to see the tower pancake. It was completely shocking to me because we hadn't seen any of this. We were in a bubble. So to go from lost in detail, trying to write everything down, to watching video of this tower pancake, it just shocked me. All I could think was I just saw thousands of people die. And the magnitude of it set in at that moment.

The mood was somber, but we were focused. [The reporters] were having discussions like, "So where do you think we're going to land? Do we need to plan in the event that wherever we land is not in the United States? How are we going to know if they don't tell us where we are exactly?" We were in such an unprecedented situation.

As we were [about to land], Ari came back to talk to us. He told us we were going to an undisclosed location and "we ask you to please turn off your cell phones and pagers because our concern is they would emit a signal that the terrorists could pick up on." When he said that I'm thinking we can't not use the phones. We have to use the phones to file.

At this point, one of the camera guys on the plane said, "Ari, we're landing on TV. " He looked and saw it and was like, "Okay, cat's out of the bag. We're going to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana." They just didn't want us giving away the president's location. You do have to think, should I do my journalistic duty and report absolutely every fact that I know? Should I choose to be judicious because this will affect my safety too? If anything happened to President Bush, it was going to happen to us too. So I did as much as I could balancing my journalistic duty with my personal safety.

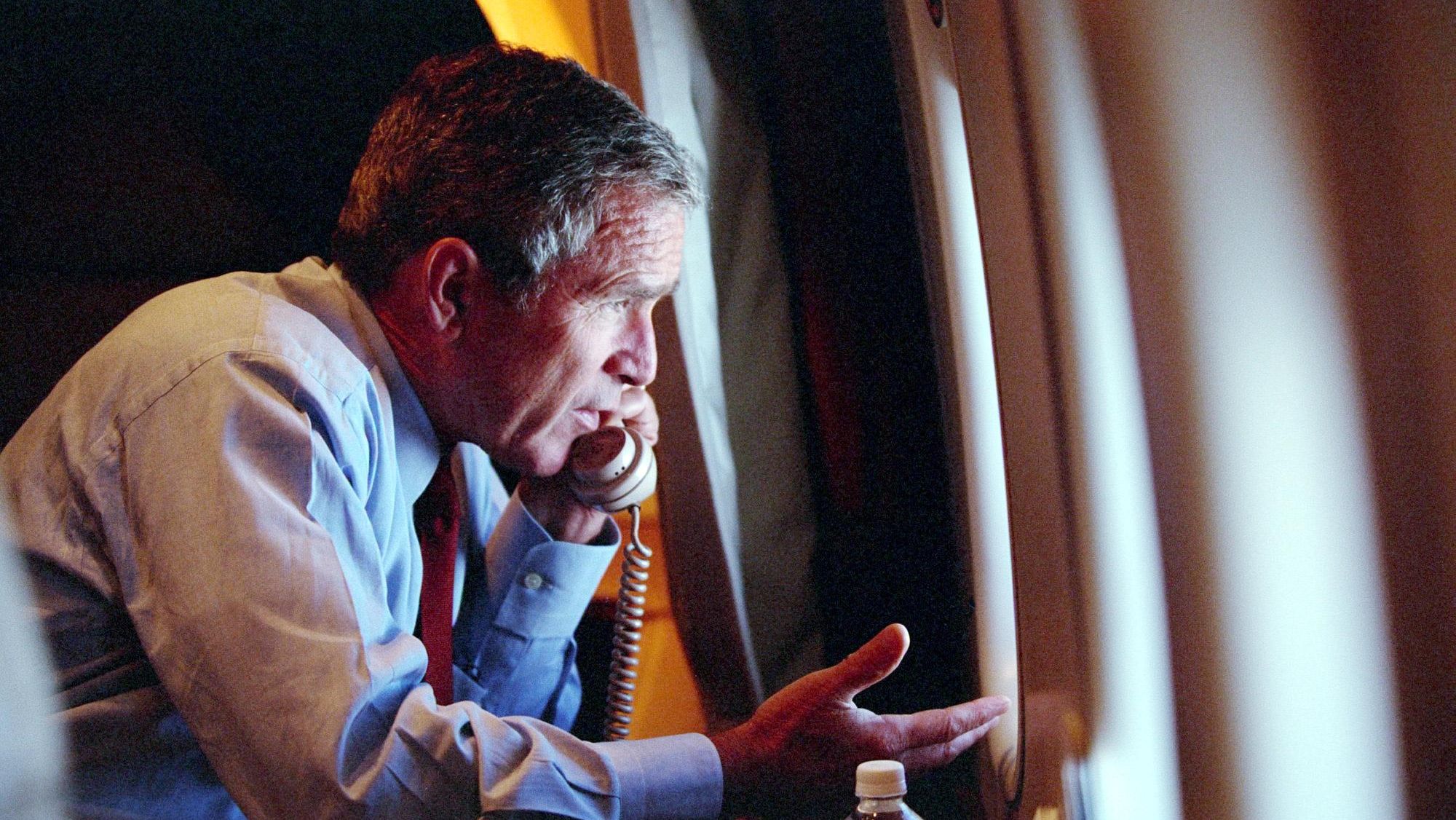

President Bush speaks to Vice President Dick Cheney on board Air Force One on September 11, 2001.

Once we were on the ground, they told us it was okay to use our phones to contact our desks. They also said the president was going to make a statement that he would film here for release to the broadcast networks once we left Barksdale. I held my phone and tape recorder out to capture the president's words so [my colleague in Washington] could hear what he was saying. He said some remarks to the effect that "our nation has been attacked. We are planning what we can do. I am going to go back to Washington." They said they'd give us a few minutes to file [our stories] and took us to a room adjacent to where he made his speech that looked like a classroom.

I had to do a long-legged run to get to that room really quickly. I unplugged the phone line and shoved it into my laptop. We had a little under 10 minutes, and I pounded out notes, hit send, and asked the [AP news] desk to clean it up. They had one of my colleagues in the bureau back in Washington filing for me under my byline.

I felt this was a moment in which I'd be judged and I didn't want to fail. If I came up short, how much harder would it be for another Black girl to do this?

While we were waiting [to board Air Force One] we were like, "Well, who's going to go with the president?" There had been some talk that they might activate the nuclear bunker pool, which typically consists of five people: the wire service reporter, the wire service photographer, a two-person camera crew from the TV networks, and a radio reporter. So I said, "Well, I'll go." And then one of my colleagues said, "Well, I'll go." Out of the [members of the press], there were five of us who were women. And out of that five, two of us were women of color. I was sitting there thinking, I don't want to explain to my bureau chief how I managed to get him checked out of this historic pool.

At that point, Johndroe, the [assistant press secretary], came onto the bus and said, "The following people go with me. The rest of you are going back to Washington on a support plane." And he said, "AP photographer, AP reporter, ABC radio, and CBS crew...let's go." As I was gathering up my stuff to leave the bus, I could hear Jay [Carney] and Judy [Keen] raising a complete stink in the back of the bus saying, "No, we need to go. We need to be on this plane." I imagine the rest of our colleagues gave [Johndroe] the "what for?" too. But we were having to move out so fast, I couldn't linger for that discussion.

I never had [done] anything like this. And I was just trying to make sure I did my job well. I felt this was a moment in which I'd be judged and I didn't want to fail. If I came up short, how much harder would it be for another Black girl to do this? I couldn't fail. I couldn't become afraid. I couldn't slip. And yet it was one of those profound moments in time so I said, all I can do with it is the best I can do.

It was about midday, around noon or one o'clock central time, when we left Louisiana and went to the president's chosen location for his safety, which was a strategic command [center] in Nebraska. When we arrived there, I was struck by the contrast between the magnitude of what we were experiencing during that moment and the serenity of the environment. It was completely bucolic. Leafy grounds. It wasn't too cold, it wasn't too hot. It looked like a college campus. That with the stark contrast of soldiers armed with machine guns meeting the plane on the tarmac ready to fire at a threat was sobering. It kept us cognizant of what exactly was going on beyond where we were.

[A press aide] told us, "We don't know when we're going back to Washington. Arrangements have been made for you." And I'm like, okay, so this could take a week. Who knows? Then they took us by motorcade to a building. They said President Bush was going to get a national security briefing there. He was surrounded by his agents in tight formation and they took him to an elevator shaft. I asked Ari, "Is he going to the bunker?" Because part of the nuclear bunker pool plan is that the wire correspondent is supposed to go with him (at least that's what we had been told). Ari said, "No, he's going in for a national security briefing." And I said, "It's just an elevator shaft. How is he going anywhere but to a bunker?" Then we watched the president depart to go get his briefing.

I used that time to charge up the batteries [on all my devices] and talk to my bureau. They wanted me to give them a first-person account [of the day], so I began working on that. After about two hours [the White House press aides] eventually came back and said, "Okay, we're headed back to Washington."

It was sort of a quiet flight back, although I looked out the window and could see the F-16 fighter pilots that were on the wings of the plane. They were close enough for me to make out the outline of the pilot's face. I thought about my sister's prayer. Angels on the wings.

During the flight, President Bush came to check on people in the back of the plane. [AP photographer] Doug Mills was standing in the aisle with his camera and the president was standing in the doorway between the secret service cabin and our cabin. I was seated in front of the TV right beside the door with my laptop open because I was working both on a pool report and my story.

Doug said, "Rough day, huh?" and the president blew his cheeks out. Then he said, "But no thug is going to take our country down." So I was sitting there with my laptop sneak typing: "No thug is going to take our country down." The president heard my fingers on the keyboard and he turned and yelled, "Hey, off the record!" Now that left me with a dilemma because I had this great quote from the president. Do I stick it in the pool report and then ask the White House, "Can I have a secure line so that I can go blab about what the president just said?" Which would then lead to a censorship battle in the middle of a national security emergency. Is it worth all that? I decided it wasn't because we were on our way home and it could wait until we land when I'm back in control of my own communication.

"I just want to be able to inspire all of our young women to do this work because our viewpoints matter," says Ross. "I can't begin to tell you how much joy I feel to see the women doing this work now in larger numbers than when I was on the beat."

Once we landed at Andrews Air Force Base around sunset, they immediately took us by helicopter back to the White House. As soon as my feet hit the White House briefing room I said, "I have a verbal pool report. One last pool report." And about six reporters came to hear it. Everybody else was gearing up because the president was about to address the nation. The reporters who gathered for [the verbal pool report] got [the quote]. But when the president began his speech to the nation, he said a similar line. So that one little quote got lost to time. It was one of those situations where, if we were equipped with today's technology, it would have survived.

The president addressed the nation around 8 p.m. I worked for the next five or six hours and I finally left the White House a little before 2 a.m. It was already September 12th. I don't remember [how I got home], but I do remember seeing tanks in the street.

I had to stay awake to put the finishing touches on my first-person account, but first I took a minute to call my mother. I was like, "Hi, mommy." She dropped the phone and I heard her yelling, "Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, Jesus" for a few minutes. She came back to the phone finally and said, "Whew lord, I'm so glad to know you're safe. They've been keeping news from me all day. Why didn't you call me before now? Don't you ever do this again." I said, "I didn't want you to worry." And she said, "I'm always going to worry, but I'm glad you're okay." After that I turned in my story.

Before I went to bed, I sent an email to the people who were blowing up my personal email throughout the day. I said, "Thank you all for checking on me. Yes, I was with the president yesterday and suffice it to say, I am fine. America is not. But we will be. And let's just pray we'll understand it better by and by."

RELATED STORY

Rachel Epstein is a writer, editor, and content strategist based in New York City. Most recently, she was the Managing Editor at Coveteur, where she oversaw the site’s day-to-day editorial operations. Previously, she was an editor at Marie Claire, where she wrote and edited culture, politics, and lifestyle stories ranging from op-eds to profiles to ambitious packages. She also launched and managed the site’s virtual book club, #ReadWithMC. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.