Melinda Gates' New Book 'The Moment of Lift' and Gender Equality

"This could be our once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to take meaningful action."

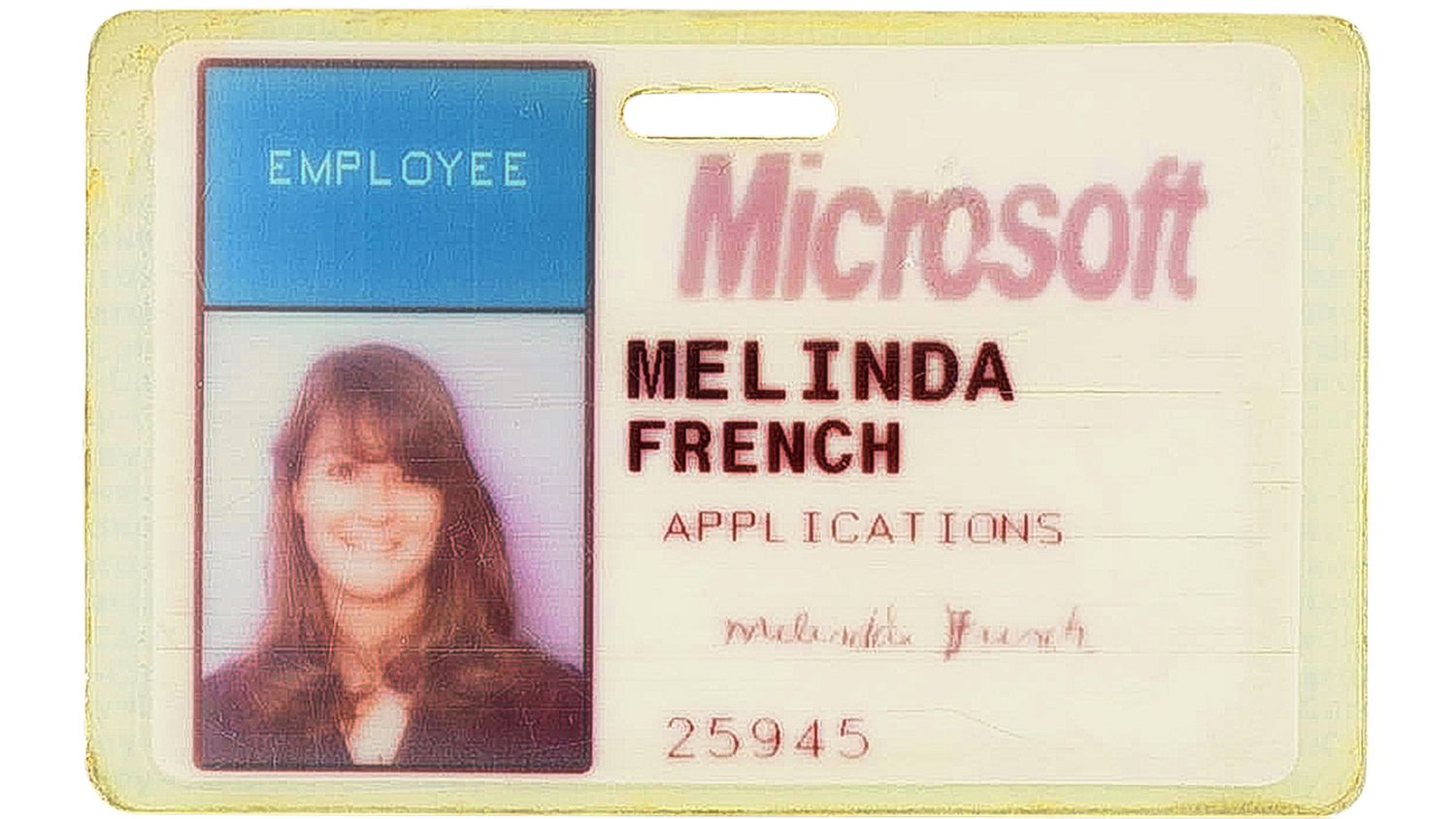

After almost a decade at Microsoft, Melinda Gates has devoted her life to empowering women. From her work at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which focuses on poverty and health abroad and public education in the U.S., to investing in venture-capital funds that support companies started by women and people of color, to starting Pivotal Ventures, which opens pathways to technology to girls, and Evoke, an online community for and about change makers, she is steadfast in her commitment to equality for all. In The Moment of Lift (Flatiron Books), she mines her life to illuminate issues affecting women and girls worldwide. Here, she discusses her career, the foundation’s efforts, and how to lift up all women.

Marie Claire: You mention a demanding schedule and the fact that there wasn’t a formal family-leave policy in place while you were at Microsoft. What’s your advice for current tech founders whose employees work 80-plus hours a week, which often creates an environment that can feel impossible for women, particularly those with children?

Melinda Gates: When employees believe they’re in an unfair situation, they leave. An organization called the Kapor Center recently conducted a study looking at who is leaving tech and why and found that employees from all backgrounds cited unfairness more than any other factor as a key driver of their decision to go. The bottom line is that if you want to build a great company that helps contribute to a better future, you need women and people of color to be a part of it.

Diversity matters—for innovation, for product development, for driving profit, for meeting future workforce demands, and, most important, for closing economic and wealth gaps. So my advice to tech founders is that they should treat creating an equal and inclusive work environment as they would any other business priority. They should put resources behind it, measure progress against targets, and make sure their policies reflect these values and goals.

MC: You met your husband at a company dinner shortly after joining Microsoft as a product manager. In light of #MeToo, do you see dating the boss any differently now?

MG: When I started dating Bill, I did a lot of reflecting about what it would mean for me. I’d worked really hard to get where I was, and I didn’t want anyone looking at me differently or thinking of me as just Bill’s girlfriend. That said, I think there’s an important distinction to be made here. Our story is about a relationship that just happened to start in a workplace—not a story about an abuse of power. When Bill asked me out, he did it in a way that made me feel I was absolutely free to say no and that if I turned him down or ended the relationship at any point, it would have no bearing on my career. If I’d said no and he’d kept asking, that would have been different. But he didn’t, and by saying yes to a date I wanted to say yes to, I opened my life up to a love story that’s lasted 30 years.

These distinctions matter. Because when the story is about abuse or assault or harassment, that’s something that needs to be taken very seriously. The women—and men—who are sharing their #MeToo stories are calling us to action. They have to remain at the center of this movement and the center of our response to it, which I hope includes strong workplace protections for workers far beyond just Hollywood and Silicon Valley.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: Are there things you’ve seen in your foundation work that cause you to lose hope? And what have you seen that fills you with unbridled optimism?

MG: Confronting the realities of extreme poverty and entrenched inequality doesn’t get easier—and that’s important, because it shouldn’t. I learned early on that to do this work well, I had to be willing to let my heart break. If you turn away from what you’re seeing to protect yourself, then you’re not taking away what you should be.

But another way to think about it is that your heart shouldn’t just break—it should break open. Because that makes it possible to let in the good too. And I’ve met so many women around the world who are doing such incredible things. They’re risking their lives to deliver health care to women and children in remote places, they’re starting schools for girls who would otherwise end up child brides, they’re challenging cultural norms to insist they should have the right to decide if and when to get pregnant. They believe a better future is possible and that they can play a role in creating one. Their optimism fuels mine.

MC: Studies show if there were more women in positions of leadership, countries, companies, and organizations would be more prosperous, peaceful, and equal. What will it take for gender equity to be achieved?

MG: As you alluded to, part of that effort will require fast-tracking women in the sectors that have disproportionate influence in this country—like tech, banking, media, and law—and I think we can do that by making targeted investments in efforts to connect these women to the opportunities and resources they need to advance. But focusing only on women in elite professions is never going to be enough to create true gender equity. We also need to be dismantling the barriers holding women back everywhere—like the fact that our country is in the middle of a caregiving crisis that is disproportionately impacting women. Sixty percent of nonworking women say that family obligations are keeping them out of the workplace. What if we made it a priority to ease their caregiving burden and made it possible for anyone who wanted to return to work to do so?

Right now, there is so much energy behind the issue of gender equity in this country that I think this could be our once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to take meaningful action. I’m doing a lot of thinking about the role I can play in helping every woman seize this moment. Watch this space.

MC: In the book you recount how the woman who would have been your boss at IBM encouraged you to take a job at Microsoft if offered instead. How did that influence you as a future boss? What are other ways women can help women in their careers?

MG: I’d interned at IBM and was planning to accept a full-time offer there when my manager told me that if I got an offer from Microsoft, I should take that instead because there would be more opportunity to advance. Looking back, I think that advice was incredibly generous of her. Even though I was there because I wanted a job, she didn’t treat me like just a potential employee; she treated me like a person. She wanted to see me succeed on my own terms.

When I got to Microsoft, that’s how I tried to manage, too. There was sometimes pressure for employees to conform and try to fit the models of success we saw around us—almost all of which were male, of course. But I decided that as a manager, I wanted to create space for everyone on my team to be the best version of themselves, no more pressure to be someone else. And it turns out there were a lot of people, women and men, who were looking for that in a manager.

MC: You talk about your perfectionism—feeling you’re not smart or hardworking enough—as a weakness and that you combat it with being over-prepared. But that isn’t the solution either. What actually works in cutting yourself a break?

MG: It’s true: over-preparation is a symptom of my perfectionism, not a cure for it. I don’t know if I have a cure, but as I write in the book, I did have a sort of epiphany recently. It finally occurred to me that maybe the most “perfect” version of myself isn’t actually my best self. Maybe I’m actually a better version of myself when I’m embracing my flaws and shortcomings than when I’m trying to hide them.

MC: Women doing the bulk of unpaid work in their households is a universal issue, but we don’t have dialogues like the book’s example of Ester in Malawi, during which men and women compare their daily workloads to expose the imbalance. What can we do to show and then address the disparity?

MG: I think the answer is right there in the question: We can start these dialogues ourselves. As I explain in the book, Ester and her husband were part of a program that helped guide couples through conversations about the division of work in their households with the goal of ultimately redistributing that work more equally.

On average, women around the world spend more than twice as many hours as men on unpaid work. There is no country where the gap is zero. Before we can close this gap, we have to recognize it exists, and that’s where conversations like the one Ester had with her husband come in. The point of these conversations isn’t necessarily to mandate that everything is exactly 50-50 all the time. It’s to ensure we aren’t just making assumptions that one parent will automatically take on a certain task because that is what’s always been done.

To give you just one example of what this has looked like in our household, years ago, when our oldest daughter started kindergarten at a school that was 40 minutes away from our house, it was sort of assumed that I was going to be the one doing all the driving—and I was dreading it. So I told Bill that that was going to be a lot of time in the car for me every day, and we decided together that it made more sense for us to split the task instead. He started driving her two days a week, and eventually, other dads in the class followed suit, because they realized if Bill Gates had time to drive his daughter to school, so did they.

MC: You discuss being an outsider who can be viewed as imposing your values on communities you know little about. What do you say to those who suggest tackling problems in the U.S., which, for example, has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world, or the American South, where HIV diagnoses rates remain high?

MG: When we began this work, we started with what we believed: that all lives have equal value, and that every child on Earth deserves the chance to lead a good life. Then we looked for how we could best turn that belief into reality—how the resources at our disposal could have the biggest impact on the most people. And after studying the data, we decided that overseas, our work would focus on fighting poverty and disease, and in the United States, we’d focus on public education.

I agree that the issues you mention—maternal mortality and HIV in the United States—are vitally important, too. The question in our minds is never about which issues matter most; it’s about which ones our foundation is most equipped to drive real progress on.

MC: In your foundation work, what has proved easier than you thought to accomplish, and what has proved more difficult than you thought?

MG: I’m not sure I’d use the word “easier.” Our partners work very hard for every one of their successes. But one area where we’ve seen progress that some people didn’t expect is HIV. When our foundation joined other donors to start an organization called the Global Fund that, among other things, helped poor countries treat people with HIV, critics were skeptical. They said people in developing countries just wouldn’t be able to stick to the complicated treatment regimen. They were wrong. Approximately 20 million of those people are now on treatment—working, raising children, planning for the future.

The progress hasn’t been as clear in our U.S. education work. We take pride in learning from what we get wrong, though, and we are incorporating every lesson into our education strategy going forward. For example, one of our early strategies was about converting large high schools into smaller ones, because the evidence suggested students in small schools did better. This worked in some places, but in others the complex process of closing down schools and opening new ones was too expensive and too disruptive. We learned, however, that what made the most effective schools successful, whether they were large or small, was great teachers. So we have gradually shifted our investments to focus inside the classroom, on what happens between students and teachers, to make sure that what works in the best small schools is available to everyone. We will not stop learning and investing until all students can receive the great education they deserve.

MC: What does power mean to you?

MG: At the individual level, I think it’s the ability to shape your future and set your own agenda so you can be who you want to be in the world.

When I think about what it means to have power in society, I think Ruth Bader Ginsburg put it well when she said that she believes that “women belong in all places decisions are being made.” That’s what I’m working for. I want to see women shaping the direction of this country in all spheres—family, community, business, culture, and government. I want to see us in the places where decisions are made and having a voice in the conversations that will shape the world’s future.

A version of this story originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

RELATED STORY

Dedicated to women of power, purpose, and style, Marie Claire is committed to celebrating the richness and scope of women's lives. Reaching millions of women every month, Marie Claire is an internationally recognized destination for celebrity news, fashion trends, beauty recommendations, and renowned investigative packages.