My Immigrant Parents Love Me. They Hated My Startup

My white co-founder didn't face this challenge.

I had the makings of the model Asian-American daughter. After graduating from an Ivy League college, I pursued the standard 2+2+2 in business: hopping briskly from management consulting to private equity to business school, two years each.

But throughout, I had doubts about whether pondering “strategy” in large conference rooms while wearing heels was for me. It frustrated me to spend all day talking about how other people should build stuff, instead of building things myself. I wanted to create something that would not exist without me, instead of doing a job that someone else could do perfectly well if I suddenly evaporated.

I wanted to start a company.

But being an Asian-American daughter, I needed to get the blessing of the most important people in my life: my parents. That conversation went something like this:

“Mama, Baba, I think I’m going to start a company.”

“Why would you throw away everything? You have a good job!”

“But I’m not happy...”

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

“Happiness doesn’t put food on the table. Who is going to give you money?”

“Well, I’ve been saving, and I think I could find a job if this fails…”

“Who is going to support you when you are poor? You are 28 years old and not even married!”

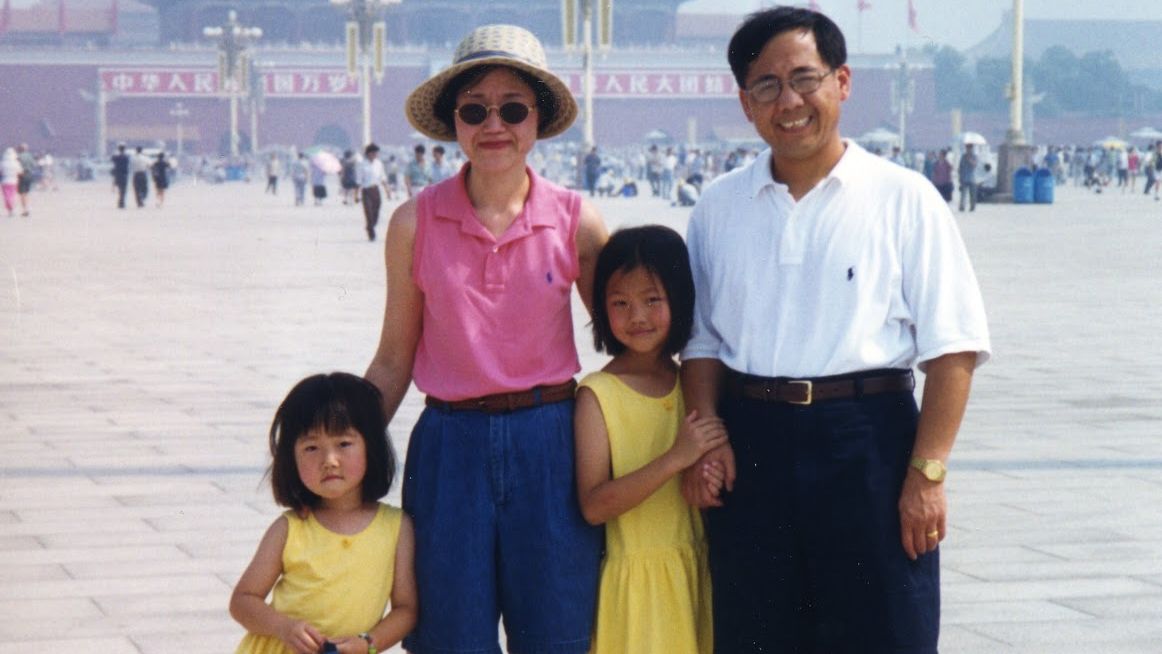

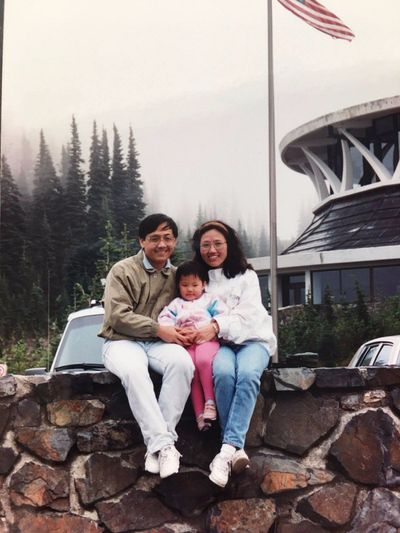

The author with her parents in Washington state, circa 1994.

For a long time, I thought that the real reason my parents didn’t want me to start a company was because they wanted status. They wanted to talk about me to their friends at large Asian family holiday potlucks, the kind where each family has taken their shopping budgets for the week and poured them into elaborate 12-hour dishes, which were always stored in mismatched two-dollar K-mart Tupperwear (it’s important to be frugal). I imagined my mother’s silent glee as she waited for someone to ask about her daughters (it’s important not to brag openly). She would respond in a lowered voice as she doled out meticulously formed spring rolls, “So nice of you to ask! Our oldest went to [Harvard/Yale/Stanford] and now does [medicine/law/banking] at [Harvard Medical School/Yale Law School/Goldman Sachs], because of the grace of God.” And the sheer magnitude of 22 years of willpower, I imagined her thinking to herself.

I resented my parents for this. How selfish of them to sacrifice me to the corporate overlords so they could claim the Best Parents Award amongst their friends. Worse, I resented myself for needing their approval. While my friends were focused on “finding themselves,” I was finding which of the three anointed paths I could follow with the least dread. So I summoned my inner Sheryl Sandberg and Leaned In.

The heavens were quick to respond. Within two weeks of starting business school, I met the person I wanted to start a business with, Patrick. We both had the desire to do something that increased philanthropy, and knew that the upcoming Great Wealth Transfer of $35 trillion could be an historic opportunity to do so. We realized that the main barrier to estate planning is that people find the process scary, complex, and expensive. What if we could help people make legal wills online in a way that is warm, intuitive, and free—and make it easy to give to charity as a part of that process? We came up with FreeWill.

I thought the reason my parents didn’t want me to start a company was because they wanted status.

I could sense my parents’ disapproval of my new venture every time I called home, and thought the answer was to hurry up and make it big. The faster we could achieve meaningful success with the business, the faster this could be another thing my parents could show off to their friends. A plan in hand, I plowed forward.

But something nagged at me. My parents are smart and good people—why couldn’t I make them understand that entrepreneurship was a worthy pursuit? The beginnings of an answer came to me one afternoon when I read a passage in A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara: “[The love one has for a child] is a singular love, because it is a love whose foundation is not physical attraction, or pleasure, or intellect, but fear.”

The word “fear” gave me pause. My parents’ immigration story from China is a familiar one: unknown people, unknown language, unknown culture, and raising children without a community of aunties to help, all so my sister and I could have a chance at a better life. They had played immigration roulette and won—two well-educated, healthy daughters, gainfully employed by name-brand firms. Just a wedding and a few babies away from the ultimate prize.

The strong families around my parents were led by lawyers and doctors and bankers. The only successful entrepreneurs they have heard of are Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs, and Bill Gates, all of whom are white men. They saw model minorities achieving the American Dream by assimilating. The people who could afford to be different didn’t have to blend in with white men—they were white men.

What I was beginning to realize was that by starting a company, I was really asking my parents to tackle another set of unknowns: companies that didn’t make money, female bosses, dual-career families, and, most scarily, intentionally sticking out.

My initial instinct was to address these unknowns head on. My efforts to explain how risk-taking should be inversely correlated to age in order to maximize cumulative returns garnered blank stares. I pointed to successful female entrepreneurs like Reese Witherspoon and Alexa von Tobel, to which they responded by sending me articles about Elizabeth Holmes with the question, “You aren’t committing fraud, are you?”

The author and her FreeWill cofounder, Patrick Schmitt, at Stanford Graduate School of Business, where they met.

But unknowns are different from fear. One is logical, the other emotional. My parents had dealt with far more difficult unknowns when they immigrated than I will ever have to face. They are veterans at handling the unknown. What was hard for them was the visceral lack of power to protect their bao bei. I remembered something I learned in business school: emotions are often our bodies’ quickest form of pattern recognition. I couldn’t point to a pattern of successful Asian American female entrepreneurs, so I would need to build a new pattern for them.

The key to making my parents to accept my life as an entrepreneur was to bring everything closer to them, so that they could feel the happiness that has filled my life since starting the company. I call home more frequently. I tell them all the things I am excited about for the upcoming day, even if it is just settling our accounting books for the month. I tell them about every new person we hire, and how proud I am of the amazing team I get to work beside.

It’s not perfect, but we’ve made a lot of progress. And I hope they feel a bit of pride that FreeWill has already helped more than 18,000 people while raising $200 million for charity. They were, after all, the original entrepreneurs when they decided to start our family in the United States.

RELATED STORY

-

Netflix's 'North of North' Transports Viewers to the Arctic Circle—Meet the Cast of Inuit Indigenous Actors

Netflix's 'North of North' Transports Viewers to the Arctic Circle—Meet the Cast of Inuit Indigenous ActorsThe new comedy follows a modern Inuk woman determined to transform her life.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Princess Beatrice's Husband Pays a Rare Tribute to These Royal Family Members on Instagram

Princess Beatrice's Husband Pays a Rare Tribute to These Royal Family Members on InstagramEdoardo Mapelli Mozzi shared some behind-the-scenes snaps from the F1 Grand Prix in Bahrain.

By Kristin Contino

-

Allow Kathy Bates to Convince You to Grow Out Your Grays

Allow Kathy Bates to Convince You to Grow Out Your GraysOne look at her new style and you'll be canceling your root touch-up pronto.

By Ariel Baker

-

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into Strength

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into StrengthBefore becoming a powerhouse cycling instructor, Selena Samuela was an immigrant trying to adjust to new environments and new versions of herself.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable Future

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable FutureAmy Domini and her firm, Domini Impact Investments LLC, are inspiring a greater and greener world—one investor at a time.

By Sponsored

-

Power Players Build on Success

Power Players Build on Success"The New Normal" left some brands stronger than ever. We asked then what lies ahead.

By Maria Ricapito

-

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wise

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wiseFeatures Yes, maybe you eat paleo and have mastered crow pose, but do you practice financial wellness?

By Sallie Krawcheck

-

The Book Club Revolution

The Book Club RevolutionLots of women are voracious readers. Other women are capitalizing on that.

By Lily Herman

-

The Future of Women and Work

The Future of Women and WorkThe pandemic has completely upended how we do our jobs. This is Marie Claire's guide to navigating your career in a COVID-19 world.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POC

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POCFor people of color, many of whom prefer to WFH, inclusive coworking spaces don't just offer a place to work—they cultivate community.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?The pandemic has forced our work friendships to evolve. Will they ever be the same?

By Rachel Epstein