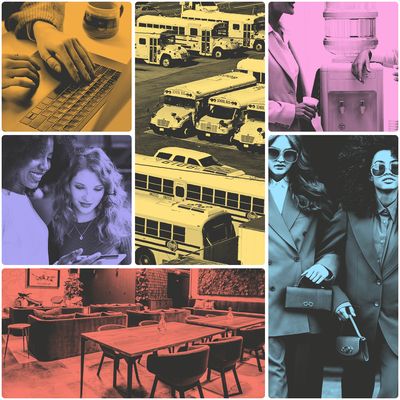

On Being a High-Functioning Depressed Person

I was a star at work but it turned out to be a mask for a lot more.

Tell me if this sounds familiar: In my late 20s, I thought I had the world by the tail. I was hustling at a very big-deal job, dating elite men whenever I wasn't at the office, and always racing to keep up with my important, fast-paced life.

I was exhausted, but if you'd asked me, I would have said I was happy.

Occasionally though, when I would get a rare moment to myself in a cab or late at night after I collapsed in bed, and I felt like something was wrong. An anxiousness would suddenly course through me out of nowhere. Dark, ominous thoughts would find me and not let go.

Somewhere along the blur of deadlines and meetings, I decided I just wouldn't pay attention to them. It was easier to stuff my feelings away and concentrate on work.

Then, one night at a very glamorous party, I started to cry for no reason. My date took me home and I cried for the next five days.

Then, one night at a very glamorous party, I started to cry for no reason. My date took me home and I cried for the next five days. Five. Days.

I didn't eat. I didn't sleep. I just cried. It was excruciating—and I had no idea what was happening to me. But the most terrifying part was that I physically couldn't make it stop. For the first time in my very controlled life, I had no control at all.

Once I was finally able to pick up a phone, a psychiatrist told me I was experiencing a nervous breakdown. My brain chemistry had, apparently, short-circuited from stress.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

He immediately put me on anti-psychotic drugs—Thorazine and Haldol—just so I didn't jump off a building. (Which was, honestly, pretty tempting at the time.) The drugs flattened me, but they at least stopped the crying.

I quit my job, the one thing I valued most. I had to. And over the course of the next year, I went through intensive therapy and a lot of different medications until they found the right ones.

The whole time, I kept my breakdown a secret. I didn't want anyone, especially colleagues, to know that I had crossed a mental threshold that was beyond my control.

And this is when I stepped back, decided things needed to change, told my bosses to stop stressing me out—to stop stressing us all out—and figured out how to make everything work while still being a high-powered career woman in a high-powered field. Right?

Wrong.

As I was starting to feel healthy again and scrape my life back together, I decided maybe I was well enough to start working a little bit. I switched industries from public relations and advertising into news, and ended up working full-time at CNN for a live two-hour show daily. (Katie Couric sat next to me the first couple of years.) But when you're working with live television, there's no room for error. You're dealing with seconds, not minutes. The climate was just as stressful, if not more so, than my previous job—and I found myself slipping right back to where I was.

I became a machine, always aiming for perfection. Ignoring how I felt.

My brain chemistry had, apparently, short-circuited from stress.

Around the same time, I went to a new psychiatrist who said, "Oh you don't need these drugs." I was performing well at work, so what was the point?

Cut to me, sitting at my desk at CNN, absolutely panicked, afraid to look up, pretending to be on the phone so no one would talk to me.

I got back on the meds.

That's when I realized the larger problem: I was depressed but still able to function at a high level, churning out work at lightning speed. It's actually a known condition, called presenteeism—you work at an office, you arrive every day on time, you work your job, you may even do great things, but you're ultimately just playing a role. A worker-bee robot. You're not feeling anything—a common marker of depression.

To the outside world, many people who are depressed and miserable are acting like they're not. And some of us are really great actors and actresses—that's the part a lot of people don't see.

Over the last 25 years I've been on probably between 15 and 20 different medications, sometimes as many as five medications at the same time to help me sleep, to think more clearly, to allow me to function on a daily basis because my condition is that bad.

When I came out the other side and started telling friends I was writing about my struggles, they were always so taken aback: How could a hard worker like me, with so much professional success and drive, suffer from depression? And for so many years?

But that's the thing about depression: It can grab hold of anyone, even the over-performing alphas who never stop for anything. Not even a nervous breakdown.

Schatzie Brunner is the author of The Face of Depression.

If you or someone you know is suffering from depression or anxiety please contact the National Alliance on Mental Illness HelpLine Monday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00, p.m., ET at 1-800-950-6264 or visit nami.org.

-

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose

Princess Anne's Unexpected Suggestion About Mike Tindall's Nose"Princess Anne asked me if I'd have the surgery."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding Comment

Queen Elizabeth's "Disapproving" Royal Wedding CommentShe reportedly had lots of nice things to say, too.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down"

Palace Employees "Tried" to Get King Charles to "Slow Down""Now he wants to do more and more and more. That's the problem."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into Strength

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into StrengthBefore becoming a powerhouse cycling instructor, Selena Samuela was an immigrant trying to adjust to new environments and new versions of herself.

By Emily Tisch Sussman Published

-

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable Future

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable FutureAmy Domini and her firm, Domini Impact Investments LLC, are inspiring a greater and greener world—one investor at a time.

By Sponsored Published

-

Power Players Build on Success

Power Players Build on Success"The New Normal" left some brands stronger than ever. We asked then what lies ahead.

By Maria Ricapito Published

-

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wise

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wiseFeatures Yes, maybe you eat paleo and have mastered crow pose, but do you practice financial wellness?

By Sallie Krawcheck Published

-

The Book Club Revolution

The Book Club RevolutionLots of women are voracious readers. Other women are capitalizing on that.

By Lily Herman Published

-

The Future of Women and Work

The Future of Women and WorkThe pandemic has completely upended how we do our jobs. This is Marie Claire's guide to navigating your career in a COVID-19 world.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POC

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POCFor people of color, many of whom prefer to WFH, inclusive coworking spaces don't just offer a place to work—they cultivate community.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?The pandemic has forced our work friendships to evolve. Will they ever be the same?

By Rachel Epstein Published