Dermatology Deserts: What to Do If You Live in One

With skin doctors flocking to the metropolitan edges of the U.S., rural residents are left to fend for themselves. Can the system be fixed?

In the Mississippi Delta, one of the poorest areas in America, residents don’t head to a specialist’s office to check their moles or fade their dark spots—they line up at Rolling Fork High School once a month. One medical expert is stationed there just 12 days a year to examine every local adult and child for any of the nearly 3,000 diagnosable skin conditions. If that seems problematic, it is: The Delta is just one of many dermatology “deserts” in America.

Most of these problem areas are located in the Midwest, the rural South, and the central North. “There is less access to healthcare overall in rural towns compared to urban areas of the U.S. Many rural parts of the country don’t even have a hospital, much less specialty care like dermatology,” says sociologist Shannon Monnat, Ph.D., an associate professor at Syracuse University and co-director of the university’s Policy, Place, and Population Health Lab. “These residents have very few options. They can travel long distances to access the care they need, attempt to find ways to treat skin issues on their own—which can be expensive and ineffective—or simply suffer with the physical and emotional pain and discomfort from their skin issues.”

The nearest dermatology practice to Rolling Fork, in the heart of the Delta, is about 90 miles away in Jackson, Mississippi, and it can take up to three months to nail down an appointment there. “Would you care to guess the percentage of people who live in the poorest part of Mississippi that actually show up for that appointment 90 miles away?” asks Robert Brodell, M.D., the chair of the dermatology department at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, which helps staff the clinic at Rolling Fork High School. He’s not being facetious; he has an answer: “It’s 14 percent,” he says. “Some residents don’t have transportation, or money for the gas, or they lack childcare. Whatever it is, they won’t make it.”

With their examinations being put off for months at a time, patients live with undiagnosed conditions that can escalate quickly. And we’re not just talking about rashes or infections. Cancer can grow unchecked and metastasize without treatment, especially if it’s a melanoma, the most aggressive form of the disease. In fact, delaying treatment of stage I melanoma just four weeks increases the chance the patient will die, according to a Cleveland Clinic study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

And skin cancer is more common than many people realize: Every day, about 9,500 Americans are diagnosed, and nearly 20 die of the disease. Dermatologist Karen Edison, M.D., a professor at the University of Missouri, tracks the developments of these cancers in her home state. “We know that the thicker the melanoma is, the higher chance you’ll die of the cancer,” she says. “We’ve seen this is Missouri. The rate of this happening is definitively higher in areas farther away from where dermatologists practice.”

Though there were about 9,600 dermatologists practicing in the United States in 2017, that’s only enough to properly service 50 percent of the country’s population, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the most recent data available. And many specialists work in urban areas, leaving states that are mostly rural, like Mississippi and Missouri, with fewer dermatologists per capita than elsewhere. Ninety-four percent of privately insured Americans don’t make it to the derm annually, as recommended. This means primary care doctors shoulder the burden of care.

While general practitioners can treat basic skin conditions, many aren’t trained in dermatology—or other specialties. “Primaries have a tough problem,” says Dr. Brodell. “They’re trying to do dermatology, cardiology, pulmonology, and other specialties at once. And if they don’t have access to consulting specialists, there’s a lot of pressure on them to do the best they can. They may well have patients tell them that they won’t go anywhere else and say, ‘You’re my doctor, so I’m sticking with you.’” But that can have devastating effects, particularly when it comes to chronic conditions that require immediate attention, like painful cystic acne, lupus-related lesions, and psoriasis.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Because the lack of dermatologists in rural areas is a systemic problem, the fix isn’t simple. In an attempt to shrink dermatology dead zones, some universities provide incentives like grants to graduates who agree to work in rural areas. And many universities in underserved states make it their mission to encourage doctors to go where they’re needed most. “At the University of Missouri, we have a pretty good track record of training people to go to underserved area,” says Dr. Edison. “We have a lot of our former graduates stationed around the country, but it’s never going to be enough.”

That’s why it’s so important to empower general practitioners with more training and access to services. “It’s incumbent upon us to do the best job we can teaching dermatology during training for primary care,” says Dr. Edison. “We can also provide ongoing access to care by using technology, such as teledermatology services.”

Live interactive teledermatology uses video conferencing to connect patients and their primary care doctors with dermatologists and specialists from around the country—or around the world. “Its flexibility is what makes it attractive,” says Dr. Brodell. Many derms are beginning to offer teledermatology appointments that work similarly to Skype for those patients who can’t make it to the office in person. These can be arranged over the phone through a dermatologist’s office, and your primary care physician can recommend one they trust. This technology helps derms time-manage, too: They’re able to tuck into their laptops at home after-hours and help a few more patients per day, especially when a case is urgent.

Another variation of the service is a store-and-forward format: Providers at free clinics and offices in underserved areas can take photos and notes during a patient’s visit, then forward these materials to trained dermatologists for feedback. Many of these programs are free and staffed by specialists who volunteer their services. (If your local clinic or primary-care practice says doesn’t offer this service, you can help change that: Tell them that the American Academy of Dermatology can add a new practice to its AccessDerm program in as little as two weeks. Send them here for more information.)

There are also telemedicine providers that allow patients to connect with dermatologists directly and send in digital photos for a consultation. But, warns Dr. Brodell, these services aren’t as dependable. “I’m not saying they don’t have their place, but of these various programs, some won’t even ask for a primary care doctor to report back to. A large number of them lack two-way communication,” he explains. This means the person you’re consulting wouldn’t be in contact with your primary care doctor to discuss the diagnosis (and vice-versa), which could disrupt communication and treatment.

There’s another issue plaguing Internet-based healthcare: You may not know who you’re connecting with. “A patient can pay $50 to get an opinion and be dealing with someone who is licensed in another country or not licensed at all. And they’ll just give their best guess based on initial image was provided to them,” he says. If a dermatologist-direct service is the only option available to you, Brodell recommends asking the doctor where they practice, where they’re licensed, and if they can provide a record of their diagnosis to your primary care doctor. These are a few simple ways to tell if you’re dealing with a reliable outlet.

The ability to see a dermatologist may seem like a luxury to many people in America, but it’s a vital service that should be available to everyone. And that’s not just because dermatologists identify and treat skin cancer. The conditions these doctors treat—acne, eczema, psoriasis—impact a patient’s overall health. “Many skin issues can be embarrassing, leading to social isolation and depression. The ability to interact confidently with others impacts every facet of life,” says Dr. Monnat. “Dermatology shouldn’t be viewed as a secondary or optional health care service.”

Related Stories

Taylore Glynn is a former beauty and wellness editor for Allure. Previously, she served as beauty and health editor at Marie Claire and Harper’s Bazaar, and her work has appeared in Refinery29, Town & Country, Compound Butter, and RealSelf. She holds a master's degree in English and Creative Writing from Monmouth University. If you need her, she’s probably at the movies, braising a chicken, or evening out her cat eyeliner.

-

Taylor Townsend Sea Mosses Her Way to Better Wellness

Taylor Townsend Sea Mosses Her Way to Better WellnessThe tennis star serves up self-care between sets.

By Siena Gagliano

-

What to Know About the Cast of 'Resident Playbook,' Which Is Sure to Be Your Next Medical Drama Obsession

What to Know About the Cast of 'Resident Playbook,' Which Is Sure to Be Your Next Medical Drama ObsessionThe spinoff of the hit K-drama 'Hospital Playlist' features several young actors as first-year OB-GYN residents.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Duchess Sophie Stepped Up to Represent King Charles at Event Amid Calls for King Charles to "Slow Down"

Duchess Sophie Stepped Up to Represent King Charles at Event Amid Calls for King Charles to "Slow Down"The Duchess of Edinburgh filled in for The King at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

By Kristin Contino

-

Everything You Need to Know About Marie Claire’s Skin and Hair Awards

Everything You Need to Know About Marie Claire’s Skin and Hair AwardsCould your brand survive an editor testing session?

By Ariel Baker

-

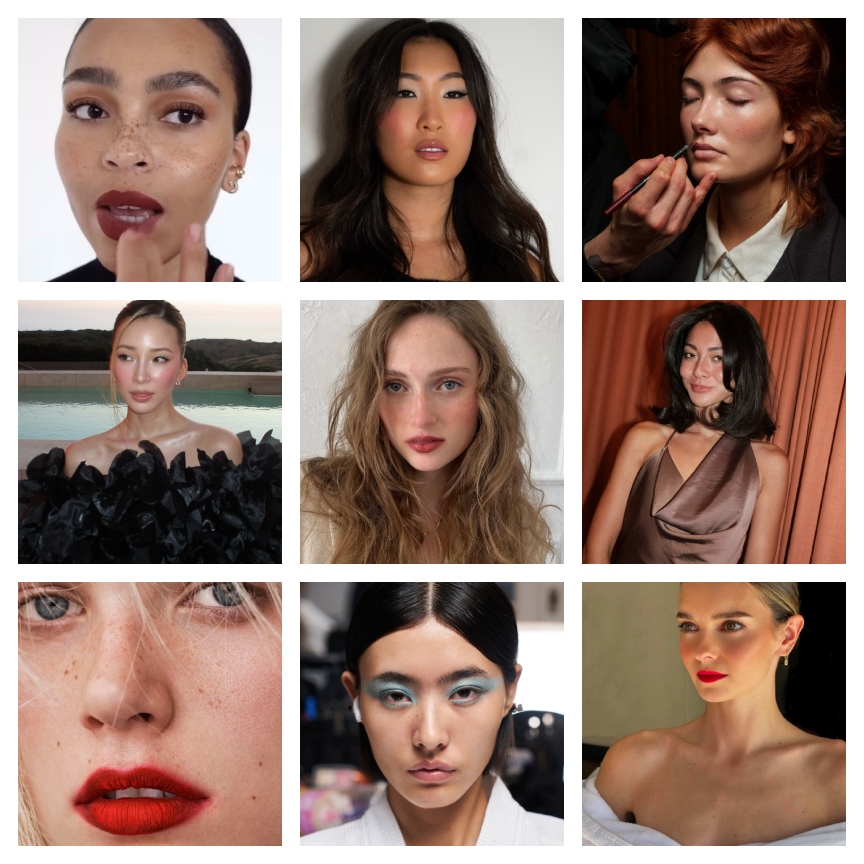

The 11 Best Spring Makeup Trends Are Sexy, Sensual, and Perfectly Luminous

The 11 Best Spring Makeup Trends Are Sexy, Sensual, and Perfectly LuminousIt's dew or die time.

By Jamie Wilson

-

Simone Ashley’s Indie Sleaze Glam Is a Cool-Toned Dream

Simone Ashley’s Indie Sleaze Glam Is a Cool-Toned DreamThe actor was spotted in New York City looking like the epitome of cool-toned beauty.

By Ariel Baker

-

The 10 Best Hair Growth Shampoos of 2025, Tested by Editors

The 10 Best Hair Growth Shampoos of 2025, Tested by EditorsExpensive and healthy-looking hair on lock.

By Marisa Petrarca

-

New York Fashion Week’s Fall/Winter 2025 Best Beauty Moments Are a Lesson in Juxtaposition

New York Fashion Week’s Fall/Winter 2025 Best Beauty Moments Are a Lesson in JuxtapositionThe week's best beauty looks were a maximalism master class.

By Ariel Baker

-

Nécessaire's Extra-Strength Deodorant Outlasts an Editor's Sweatiest Test: Fashion Week

Nécessaire's Extra-Strength Deodorant Outlasts an Editor's Sweatiest Test: Fashion WeekEven with my hectic schedule, I've never smelled better.

By Halie LeSavage

-

Lily-Rose Depp’s Cool-Toned Makeup Is So ‘90s Coded

Lily-Rose Depp’s Cool-Toned Makeup Is So ‘90s CodedClean girl meets grunge.

By Ariel Baker

-

The 15 Best Foundations for Mature Skin, Tested by Women Over 50

The 15 Best Foundations for Mature Skin, Tested by Women Over 50It's perfect for mature complexions.

By Siena Gagliano