The Scars You Don't See

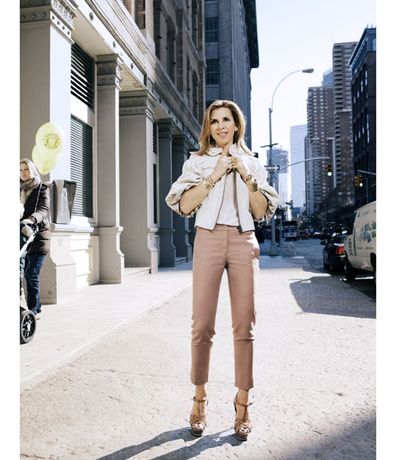

A brutal attack nearly killed event planner Jennifer Gilbert two decades ago, but a bold career move gave her reason to celebrate again.

I WAS A SMILEY 22-YEAR-OLD with long hair and dimples. I remember exactly what I was wearing — black flats, a tan linen wraparound skirt from Ann Taylor, and a black T-shirt. As I walked along, I caught my reflection in store windows, checking out how I looked: a sophisticated woman who felt proud and invincible after a year of working abroad.

I'd been back from London just a week when I took the train into downtown Manhattan to visit my friend Andrea. The doors to her building were propped open because a couple of men were there working on their motorcycles. I cruised through the front door without buzzing to get in, and smiled and waved at the men. The hallway was empty.

I rang the doorbell, then heard a noise. I looked to my left, and walking toward me down the hallway was a man, about 250 pounds and carrying a backpack. It was odd, I thought, the way he was walking right up against the wall, on a beeline to run into me. I rang Andrea's doorbell again. The man's head was down, looking toward the floor, and then his gaze — just the eyes — shifted up. What I saw in those eyes was terrifying. It wasn't lust, or drug-fueled rage, or insanity of any kind. It was pure hate. Looking back on it now, the most amazing thing about what happened next wasn't the attack, it was the way my brain worked. I kept thinking the entire time. Never once did I stop calculating what might come next. Never once was it a blur.

There was a sharp, medicinal smell, and I opened my eyes to bright light overhead. I was awake, which meant I was alive. Oh, my God, I was alive. The doctor saw that I was conscious, and the first words I could think to say to him were, "I'm here."

I was silent while they finished sewing me up. I don't know exactly how many stitches it took. Most of my wounds were punctures. I was told I was lucky that the attacker had used a screwdriver and not an ice pick or knife — if he had, I'd be dead. As it was, the screwdriver sank into me but didn't slice on its way out. But the force of those punching wounds was like being beaten as well as stabbed. If I had to guess, I'd say there were close to 40 stitches — at least 15 of those just to sew up my neck. They used surgical glue for the puncture wounds. For weeks after, I'd need to use a walker.

I remember the first time I saw my parents after the attack. I was already out of the ER and in a hospital room, and I must have been in a tremendous amount of pain. The nurse had pulled a curtain around my bed, so I heard my parents' voices before I saw them. I'd been so alone, so convinced that I was going to die. I'd been ripped to shreds and somewhat sewn back together. They still didn't know that someone had tried to kill me. So the first words I said to them — the first words it occurred to me to say — were: "I'm fine, I'm fine, I'm fine."

THIS IS WHAT PEOPLE SAID to me after the attack:

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

At least he didn't get your face. At least you're alive. At least you weren't raped. I learned that this is what "at least" means: Move on. Get over it. Let's not talk about it. It could be worse, so it must be better.

This is what I asked myself after the attack: Was it something about me, how I looked, how I was dressed? Did I smile at him or say hello? What if I had turned around and seen him, told some big man on the street that someone was following me? Why didn't I notice I was being followed? Why didn't I notice he was right behind me? What terrible thing have I done in my life that I deserved this — have I not been a good enough person? In what universe is it OK for this to happen to someone?

The questions ran around in my head, a constant series of mental laps. Did I do something? Did I not do something?

I always imagined my grown-up life in big terms: successful career, handsome husband, huge family. Even though the girl who dreamed of a fabulous New York life had been destroyed that afternoon, the dream itself remained. My task was to figure out who the new me was who could make that dream come true, then rivet together my new personality without the slightest perceptible weakness. That was the only way I would be able to survive my fears without anyone on the outside being the wiser.

The result of my rebuilding was an assemblage of contradictions, all hidden beneath my shiny skin. I was a fearless fearful person. I was isolated but afraid to be alone. I was terrified of things most people take for granted — especially sleep — but the stuff that others approach with trepidation didn't even faze me. New career choices, job interviews, selling, cold-calling — that was nothing to me. I knew what it was like to almost lose everything, so the day-to-day things that cause the average person anxiety? Please. What's the worst that could happen to me — the interviewer wouldn't hire me? This is not scary stuff.

Three months after the attack, I got a job with a small event-planning business. I didn't have the faintest idea what I was doing, but I worked constantly, never taking a vacation. On some level I must have known that the more I kept moving, the less I had to think. No longer was I the nice, dimply, happy-go-lucky girl from the suburbs. The new Jen was fierce and on top of things—Type A-plus-plus. I faced down all opposition — the attacker and anyone else in the world who tried to tell me I couldn't do everything that I set my mind to. I looked them all in the eye, thrust back my shoulders, and said, You picked the wrong girl.

Around this time, one of my biggest clients, the owner of a popular club in the city, offered to be my partner in my own event-planning firm, which I'd already named in my head — Save the Date. Though I had put away all those old fantasies of a blissful future of having it all, maybe the universe would let me have this one thing, my own bouncing baby company.

The launch of my company was a welcome distraction — even if the timing was a little ill-advised. I'd managed to put a semblance of a life together — at least superficially. But internally I never dealt with the attack. The district attorney expected that it would take three years to bring my case to trial, but somehow I managed to put that knowledge on a shelf and pretend it didn't exist.

It's surreal to remember that while I was barely controlling my fear of the trial, I was also doing my day job. Neither my staff nor any of my clients ever knew I'd been attacked, much less that I was about to testify in a trial. So while I was trying to hold down the urge to throw up, I was simultaneously booking Christmas parties, choosing hors d'oeuvres, and managing my clients' freak-outs over their goodie bags. I was 25 years old, but the enormous mental and physical pressure on me made me feel 100. Other women my age were making their youthful mistakes, getting drunk in bars, doing their walks of shame the next morning. Meanwhile, I was starting a company and testifying in an attempted murder trial.

My strongest memory of the trial — other than my actual testimony — is of almost unbearable suspense. Because I was a witness as well as the victim, I wasn't allowed to sit in the courtroom and listen. The case lasted for weeks, and the wait for my call to testify was agonizing.

My attacker was found guilty of attempted murder and sentenced to 27 years without parole. After the initial waves of emotion subsided — relief, anger, anxiety, fear, abandonment — I started to actually register the sense of closure elicited by the guilty verdict. The past was done, and I'd never have to go back there again. It was finally time to close this book and write a new story.

I had heard about a course at MIT called "Birthing of Giants." A master's program for entrepreneurs, it was an intensive series of classes in all the high-level stuff: vision statements, corporate culture, best practices. This was exactly what I needed, so I applied and was admitted, along with 64 other under-40 business owners from around the world (62 were men; one of the two other women was part of a husband/wife team). As an event planner, I worked in a female-dominated industry — my employees were women, and I've always thrived on my relationships with women. Not only was this totally male-dominated environment alien to me, but I felt deeply intimidated by the other students' knowledge. Most were MBAs with all kinds of business expertise that I'd learned by my wits, not in graduate school. I felt like such a fraud.

So I put on my tough exterior armor and sat at the front of the class, absorbing the course work like a sponge but speaking to no one — at least initially. When the others were getting together for drinks in the evening, I was back in my dorm room, poring over what I'd learned during the day. I'm sure I was known as "that bitch from New York."

Over time, though, I started to warm up, and I was deeply affected by the passion of my fellow students. There was always an incredible array of speakers, and each of the business owners who attended was invited to tell the story of his or her business at some point during the course. I listened while these strangers spilled their hearts out about what their business meant to them, and how they had poured so much meaning into their work. For the first time, I felt surrounded by kindred spirits. I realized a truth that has stuck with me ever since: Everyone's got their something. Everyone in that room had a story — whether it was sickness, poverty, or some other adversity — and they had all channeled their personal challenges into something beautiful. Their stories might be different from mine, but we all had one.

FINALLY, ON THE LAST DAY of the course, I was the only person who hadn't spoken. This was at a time when the people who knew what had happened to me were a very select few, and certainly no one in my office knew. I'd never sat down and told a bunch of girlfriends what had happened, much less 64 strangers whom I'd been so intimidated by just a short time before. In telling me their stories, these strangers had shown me the respect of treating me as their equal, as if I was as worthy as they were to sit in that room.

For the first time in my life, I told a large group of people about my personal tragedy, and how my company had been born of my commitment to spend the rest of my life helping people celebrate. I said that I got up every day and helped people to laugh and express themselves, and I loved what I did. Their response was staggering to me: a standing ovation followed by dozens of e-mails telling me how much my story had meant to them. It was a life-changing experience for me to reveal myself that way among peers, and to feel nothing but respect, acceptance, and gratitude in response. It taught me that, at least some of the time, I could fully be myself — all the sides of me present and visible for the world to see.

Excerpted from I Never Promised You a Goodie Bag by Jennifer Gilbert (Harper), on shelves May 15.

-

I Used Nordstrom’s Sale Section to Craft 7 Perfect Summer Outfits

I Used Nordstrom’s Sale Section to Craft 7 Perfect Summer OutfitsThese are formulas you can rely on.

By Brooke Knappenberger

-

Your Syllabus Guide to the 'Weak Hero Class 2' Cast—Meet the Rising K-Drama Stars Playing the Students of Eunjang High

Your Syllabus Guide to the 'Weak Hero Class 2' Cast—Meet the Rising K-Drama Stars Playing the Students of Eunjang HighSo many exciting names join Park Ji-hoon in the second season of the Netflix hit.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Prince William and Kate Middleton "Continue to Push Boundaries"

Prince William and Kate Middleton "Continue to Push Boundaries""They definitely have a different dynamic compared to other royal couples."

By Kristin Contino