Somaly Mam's Story: "I Didn't Lie."

An explosive report in Newsweek last spring raised questions regarding the legitimacy of Cambodian anti-trafficking activist Somaly Mam, tainting the nearly two-decades-long work on behalf of victims that catapulted her into the global spotlight. But how do the allegations hold up? In her first interview since the scandal dominated headlines—and left her career and reputation in shambles—Mam tells her side of things.

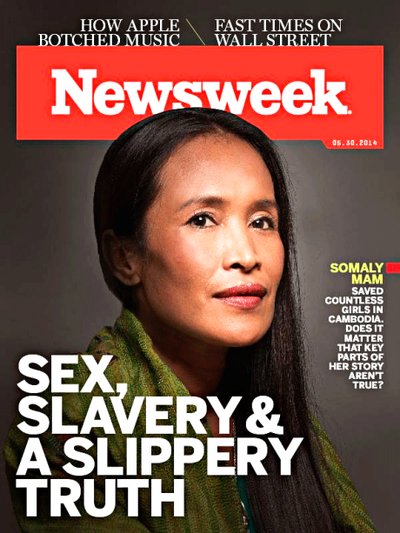

Anti-trafficking activist Somaly Mam in front of the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in August of this year.

It's a cloudy morning in Cambodia's capital, Phnom Penh, and Somaly Mam sits with a dozen young women at her home—a walled retreat from the swarm of motorbikes and rickshaws outside. Mam, famous in the nonprofit world for rescuing girls from brothels, has helped free the young women sitting around her kitchen table. Six of them are now in college; the others have become activists like Mam. They refer to her as their mother. Eating spicy soup and rice, they joke like family. "They are crazy," Mam says.

I'm here to speak to Mam about the recent allegations that have compromised her reputation and career. I asked her to agree to be interviewed with no subject off-limits. Mam has claimed for years that she herself was sold into a brothel in her youth. She has hobnobbed on the world stage with Hillary Clinton, Susan Sarandon, and Sheryl Sandberg of Facebook and Lean In fame.

This past May, Mam's life imploded after a Newsweek report left the impression that she had fabricated her life story and had encouraged a girl in her care to lie that she had been trafficked. The backlash was swift. Executives at the Somaly Mam Foundation announced her resignation. Headlines around the world labeled her a liar and a fraud, an example of the most cynical charity practices.

Amid the chaos, the young activists Mam has reared quit their jobs at the foundation in solidarity. Several of them now live with Mam. She says she told them not to quit, but to keep their jobs and collect the pay. Around her kitchen table, a palpable "us versus them" mentality prevails.

Srey Pich Loch, 23, says there was no way she could have stayed with the foundation after Mam left. "We have this life because of our mom," she says.

"And when you have no food?" Mam shoots back.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The scandal interests me because I have known and corresponded with Mam and the foundation for several years, having written about her and young women she has helped through her work. While in Cambodia, I investigated the claims against Mam and spoke to people cited in the Newsweek piece, three of whom said their views were misrepresented. One of the three, identified in Newsweek as a woman, is, in fact, a man. I also interviewed Mam's daughter Mam Sothearoath (nicknamed Nieng), who spoke publicly to me for the first time about a controversy surrounding her own past.

Of course, people can change the stories they tell. Contradictory statements, by their very nature, don't prove which version is the more accurate one. And some people may have a vested interest in Mam's redemption. Nevertheless, taken as a whole, my findings raise questions about the picture Newsweek painted of Somaly Mam. When contacted, Newsweek said it stands by its story, and the reporter had no comment.

"I didn't lie," Mam says when I ask about the allegations. So why did she remain silent? The global news cycle demands responses, I tell her. "I was not silent. I had so many lives to fix," she says, referring to the girls in her care. As the crisis grew, Mam says, she needed to reassure them. "For me, it's not about fighting with everyone," she says. "My priority was the girls. That's not silence."

Her words reveal a cultural chasm. In the West—where media savvy is part of the drill of being famous—it was assumed that, because Mam had become an international figure, she had lawyers or public relations gurus at her disposal to manage her message. Her silence for months, then, was taken as confirmation of the truth of the claims against her.

Living a world away in Cambodia, one of the poorest places on earth, Mam had a different perspective. "I didn't need a lawyer. Lawyers are all about money. You can kill people and have a lawyer, and if you're rich, you can go free," she says. "I did nothing wrong. My heart is my lawyer."

In Phnom Penh's Old Market, Mam walks with several young women she has helped at her centers over the years

TRIBAL ROOTS

In her 2005 memoir, The Road of Lost Innocence, Mam says she was born in 1970 or 1971 in a mountain tribe in Cambodia, where the women went bare-breasted and the men wore loincloths. Her parents disappeared during the Khmer Rouge era, when as many as 2 million people were executed or starved to death. Mam was left with a grandmother, who also vanished. When Mam was 9 or 10, a man who called himself "Grandfather" took her to a village along the Mekong River, she says in the book, and she became his domestic slave. She was eventually adopted by a couple who sent her to school. But Grandfather loomed, her memoir says, selling her virginity to a man when she was about 12, and later selling her to a brothel in Phnom Penh.

When she was around 21, a Frenchman named Pierre Legros helped her leave the trade. The two married in 1993 and three years later started a charity called AFESIP (a French acronym for "Acting for Women in Distressing Situations") to provide shelters for girls. Cambodia was a hot spot for sex trafficking then, and remains so today, according to the U.S. State Department. Mam and Legros later divorced, but Mam continued her work, launching the Somaly Mam Foundation in the U.S. in 2007. The foundation funded AFESIP, which ran the shelters.

In the weeks before the Newsweek story, Mam says, her foundation hired the law firm Goodwin Procter to investigate her life, as the foundation knew the story was coming. She didn't resist the probe because, she says, "I have nothing to hide." Within a week after the story came out, according to Mam, foundation executives, who declined to comment for this story, asked her to sign a letter saying she had "created and exaggerated stories about my life that were not true." The letter also said she had been a prostitute—but not that she had been forced into prostitution. "I did not sign," she says. "I have not lied. They wanted me to say sorry. I'm not sorry for my life." Soon after, the foundation cut its funding to AFESIP, which runs centers that Mam says house 170 girls.

I step away from the kitchen table to speak with Mam's daughter Nieng, who attends college in Cambodia. Mam has said that Nieng—today a raven-haired 21-year-old fashion student—was kidnapped and raped in 2006 by suspected traffickers before being found near the Thailand border. Newsweek said sources dispute those claims. Among them is Mam's ex-husband, Legros, who told the magazine Nieng wasn't kidnapped but had run away with a boyfriend.

Making her first public statement on the matter, Nieng tells me she was kidnapped. "I did not go with a boyfriend," she says. Rather, she was tricked by a young man from outside the school, she says, and driven to the town of Battambang near the Thai border. She was 14 at the time. "I didn't have many friends. I thought he was my friend," she says, speaking softly. "I didn't know much about the world." Her memories of the incident beyond that are foggy, she says, because she believes she was drugged. She says she is speaking up now because she doesn't think it's fair for people to use her own past to attack her mother. "We are two different lives," she says.

A legal adviser to AFESIP at the time, Emmanuel Colineau confirmed Nieng's disappearance and said Mam worked with the police in the search for her daughter. Colineau, now an aid worker in Iraq, says he "sincerely believes" Mam didn't fabricate the kidnapping story.

Mam, sitting along the Tonle Sap River, says she has "nothing to hide."

CHILDHOOD REVISITED

Sitting beneath a mango tree in the rural village of Thlok Chrov, a man named Thorng Ruon describes his memories of Mam as a girl, calling her a "silent and sad child." Thorng, now a commune chief, or head of several villages, recalls Mam attending school for a few years, then disappearing before graduation. His recollections are important because they mirror what Mam herself has said about her childhood—and contradict the Newsweek report. The passage in which he was cited described Mam as a happy, popular child.

In the same village, I meet with Thou Soy, the director of Mam's childhood school, who is also named in the passage characterizing Mam's childhood. He tells me the article wrongly said Mam graduated from high school: "No one knows more clearly than me," he says. "I was the director." He says Mam completed three years—fifth, sixth, and seventh grades, or secondary school at the time—and did not go to high school, but vanished. He disputes that Mam had a happy childhood and says she regularly missed class because she had troubles at home and needed to go to the river to catch fish to eat. Today, Thou is retired and works as a security guard at an AFESIP property.

Across the province, I visit Pen Chhun Heng. Identified as a woman in Newsweek, he is a man. Commune chief Thorng confirmed there was only one person named Pen Chhun Heng in the village. Pen was described as saying that Mam wasn't adopted as a child, as Mam has claimed. Pen disputes saying that. "I told the press she was adopted," he says. The story also described him as a cousin of Mam's mother, which he says isn't the case. He says he knew Mam's adoptive father but did not know Mam or her personal history, beyond the fact that she was adopted.

None of the three villagers had seen Newsweek. In rural pockets of Cambodia, people aren't in tune with the media world. People live in homes of sticks and tin, and the red-dirt roads are an obstacle course of potholes, chickens, dogs, and the occasional horse-drawn cart. Money goes to food or to monks at Buddhist pagodas that dot the countryside, guarded by multiheaded serpents. Pen, confused about journalism, asks, "Will I get arrested for talking to a journalist?"

Of the other two villagers cited in Newsweek, one couldn't be located; the other, I was told, was ill. Mam maintains she did not finish school. "If I graduated from high school, I will give you my house," she says.

In another allegation, Newsweek said a young woman confessed that she had lied about being sold to a brothel as a girl in a late-1990s documentary after Mam coached her to do so. The magazine said the girl wasn't trafficked, and that her parents put her in Mam's care only because the family was poor. I reviewed documents from an independent aid group stating that the girl had been sold by her mother to a broker for $100 in 1997, then rescued and transferred to Mam for care. That group, Khmer Development of Freedom Organization, has confirmed the documents' authenticity. (The documents did not specify what the broker did with the girl after buying her.)

Mam denies coaching the girl to lie. The journalist who made the film, Claude Sempere, says he does not believe Mam coached the girl. He says he plucked the girl and several others for filming from a group of children, and that "it's completely mad" to suggest the girl's interview was fake. The young woman, now married, couldn't be located. Mam says she lives in a Phnom Penh suburb but declined to put me in touch. The reason, she says: The young woman has problems at home because her husband hadn't known she had been trafficked until the news coverage came out.

Mam with Diane von Furstenberg in Washington, D.C., in 2009

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

I ask Mam to explain why her personal history seems jumbled and contradictory—there have been discrepancies in her own telling of the details. Mam acknowledges scrambling facts. Her explanation: "I was enslaved since I was a child." When a person is raped and abused for years, Mam says, dates and memories blur. "I was a domestic slave, then I was in a brothel. How do you count? So I was in the brothel two years, 20 years, 20 days? I was a slave."

I also ask about a Newsweek assertion that she admitted falsely claiming on a 2012 United Nations panel that eight girls were killed after an army raid on one of her shelters in 2004. Mam says she did not make false claims, but rather, spoke unclearly, as English is not her first language. She says there was a raid on a shelter by men in military uniform, although perhaps not servicemen, and she learned later that eight girls died after being taken from her facility.

One of the more horrifying aspects of the Mam controversy involves a woman named Long Pros, also known as Somana Long. Was her eye gouged by a pimp, leaving it infected and swollen, as she maintains? Or did she have an eye tumor removed by a doctor, as Newsweek says? Like many claims in this story, it comes down to one person's word against another's.

Newsweek said a doctor named Pok Thorn operated on a tumor when Long was 13, and that medical records show her eye before and after surgery. In Phnom Penh, I stop by Pok's eye clinic. As soon as I introduce myself, Pok threatens to call the police. Shouting, he says he has no medical records in the Long case and has not shown records to other journalists. Asked if he had removed a tumor, he says, "How could I remember these details? I have lots of patients. I can't remember one patient."

I also travel to Takeo Eye Hospital, where Pok worked when Long was 13, back in 2005. Program director Te Serey Bonn, also cited in Newsweek, says he remembers Long and recalls a tumor behind the eye. He says there are no medical records. AFESIP records show Long's father admitted her to one of its centers in December 2005, citing poor conditions at home. Mam says it is typical for parents to deny that children have been in brothels, as it is shameful for the family and community.

I ask Long to talk to me about her eye injury. She says she is telling the truth, and that the allegations made her feel as if she had "died again." She says she had nothing to gain from making up her story. "If I am not a prostitute, what is the reason that I should say that I was?" she asks.

Mam stands by Long. In explaining why, Mam describes the first time she met her. The girl was eating a meal at one of her shelters, away from the other girls. "Her eye was bleeding," Mam says. "She opened her mouth, and there was blood in the rice." She says Long looked dirty and "demeaned," and the other girls were afraid of her. "I told her, 'You're so beautiful,'" Mam says. "She said no one had ever told her that." Mam adds, "If a girl needs help, I help her."

A media storm followed the publication of Newsweek's story on Mam. It was assumed that, because Mam had become an international figure, she had lawyers or PR gurus to manage her message. Her silence was taken as confirmation of the claims against her. "We've been through so many things in life. I tell [my girls], you can get through this."

Today, Mam's future is uncertain. A FOR SALE sign hangs outside her house. Money is tight since she split with the foundation. At home with the young activists who live with her, she says, nodding to the group, "I cannot let myself get angry. If I get angry, they get a thousand times more angry." She adds, "We've been through so many things in life. I tell them, you can get through this."

Mam says a number of people have been supportive. One is designer Diane von Furstenberg. In an e-mail, von Furstenberg said Mam "has channeled her own sufferings by helping thousands of girls who needed help." On the scandal, she said, "I was deeply disturbed to hear the accusations against her. I do not know the details, but I do know that many people who witnessed her work were inspired and impressed. I will therefore prefer to only focus on the good she does."

In Mam's kitchen, the conversation turns to a criticism that gets the activists most riled: that it is exploitation to use the stories of girls to raise awareness of trafficking. The young women strongly disagree. They have told their own stories. They say it helps people understand the problem, and helps victims heal.

"If the girls want to talk about their story, they can," Mam says. "I don't tell anyone they have to do it. I have told my own story. Mine is enough." She pauses and adds, "Why do we need to be silent? We were silent in the brothel. Why be silent now? Enough." —Sun Narin and Melissa Bykofsky contributed to this report

Related:

Missouri Lawmakers Are Limiting YOUR Reproductive Rights

"I Escaped Life as a Sex Slave"

Girls 4 Sale

Help Stop Sex Trafficking

Why Janay Rice Decided to Stay With Ray Rice

Hillary Clinton Will Make a Final Decision About Running For President Early Next Year

14 Things Women Couldn't Do 94 Years Ago

From Food Stamps to Combatting Sex Trafficking

Photos by Luc Forsythe

Abigail Pesta is an award-winning investigative journalist who writes for major publications around the world. She is the author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down.