This Doctor Dropped Everything to Perform Abortions Full-Time

For Sara Imershein, the decision to exclusively provide abortions isn't just about women's rights—it's about her faith.

The Falls Church Healthcare Center is due for several coats of paint. Located about 30 minutes outside Washington, D.C. in Falls Church, Virginia, it's a nondescript mid-century office building in a standard commercial strip. There's a waiting room that's decorated with a mini stone fountain and displays of paper flowers.

The inside of clinic could some fresh paint too, but that's not high on anyone's priority list, admits Dr. Sara Imershein, M.D., who performs first-trimester abortions at the clinic once a week and one Saturday per month. It doesn't need to look like a spa—it needs to get one critical job done.

"We do everything we can to keep the costs down for the patients," Imershein tells me. She used to have a private OB-GYN practice near posh Dupont Circle, but after 30 years, she shut her doors. Rather than spend her retirement playing tennis or traveling to Europe, Imershein is using her time to perform abortions—exclusively. When Imershein sent out an email at the end of 2015 to let colleagues and patients know her plans, a college friend responded, "You've been working toward this ever since you were in college."

When Imershein meets with patients at Falls Church, she begins by washing her hands and introducing herself by name. She checks the patients' charts one last time and answers any remaining questions they may have. "Sometimes they'll ask, 'Will it hurt?'" Imershein says.

By that time, all patients have already undergone an "extensive" counseling session including open-ended questions designed to make sure they've chosen the procedure on their own. In Virginia, Imershein's patients have also already undergone a legally-required ultrasound and waited at least 24 hours before being allowed to see her.

"I like the idea that a woman should have to make a decision herself, and that she shouldn't be compelled for any reason except her own reasons."

"Just to make it clear, the first waiting period for most women is from when the pee stick changes color to when she picks up the phone and makes an appointment. Her second waiting period is from when she makes the appointment until when she shows up here," Imershein explains, noticeably frustrated by the fact that a woman's third waiting period is mandated by law. (There is no waiting period or ultrasound prerequisite for patients just across the border at Planned Parenthood of Metropolitan Washington, D.C., where Imershein also works.)

RELATED STORIES

Most ambivalent patients are screened out by clinic staff, but occasionally, they make it to Imershein. In one case, a woman told Imershein that another doctor had said she needed an abortion because she had been on the pill and her child would likely have complications as a result. When Imershein told her the risk of abnormality was incredibly low, their conversation quickly turned to prenatal care.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Being pro-choice means providing women with whatever health care they need, not just abortions: "I feel good when I help women make the decisions they want, and live the lives they want," Imershein says. Giving women access to whichever option is best for them not only fulfills Imershein's role a doctor, she clarifies, but as a Jewish woman too. The two roles are intertwined.

While cleaning out her office last December, Imershein found a single typed page she had written for herself before giving a speech to a Jewish group at the Washington Hospital Center in the mid-1990s. The note was tucked away in a file on methotrexate, a drug that can be used to end a pregnancy within the first seven weeks. The first sentence reads, "Abortion is not murder," and includes a paraphrased version of Exodus 21:22. According to the verse, if two men are fighting and one man accidentally hurts the other man's pregnant wife, and her fetus is lost, he must only pay a fine. The loss of a fetus is not treated like the loss of a human life.

'Dr. Imershein gives a speech at a pro-choice rally in front of the U.S. Supreme Court Building, March 2016'

In the tradition of Reform Judaism, abortion is not only tolerated but may even be commanded if the life of the woman is in danger, or if she is in physical or psychological pain, Imershein tells me. "A woman who is carrying an abnormal fetus, however, can't make the decision based on the suffering of the child, but on her suffering," she adds. "I like that. I like the idea that a woman should have to make a decision herself, and that she shouldn't be compelled for any reason except her own reasons."

Imershein describes herself as coming from a "long line of liberal Jews." Over Sabbath dinners with her family, she was taught the principles of tzedakah and tikkun olam—"justice" and "repairing the world."

Imershein's desire to help people is rooted in her faith, but her advocacy is driven by a firm belief that abortion should only be seen as a medical issue. "Women's health is medical, not political," she insists.

Even though abortion is legal in the United States, decades of lobbying by anti-choice activists have made it inaccessible in certain parts of the country. By enacting burdensome provisions that mandate counseling, extensive waiting periods, and ultrasounds, conservative lawmakers have made it harder for low-income patients and patients in rural areas to access the care they need. In 25 states, more than half of women live in a county without a clinic that provides abortion, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

In my world abortion was already legal.

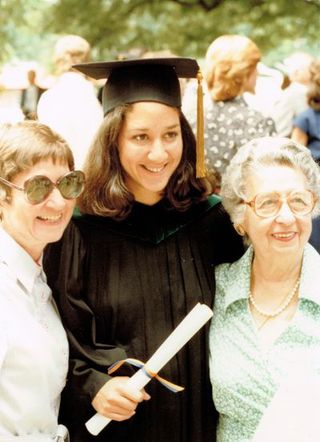

'Dr. Imershein with her mother and grandmother at her graduation from Emory Medical School in 1980.'

Imershein, who serves on the board of the NARAL Pro-Choice America Foundation and instructs medical students in abortion techniques at The George Washington University, sees her work as part of a larger effort to depoliticize women's bodies. She cites second-wave feminists like Germaine Greer, Gloria Steinem, and Bella Abzug as great influences on her views on women's rights. During our interview, she pulls out a copy of Florynce Kennedy and Diane Schulder's 1971 Abortion Rap, which documents the testimonies of women who challenged the constitutionality of New York State's abortion laws in 1970. Alongside descriptions of pre-Roe abortions, the book includes a theological take from Rabbi David Feldman, who wrote extensively on the permissibility of abortion in the Jewish tradition. "It was the first time I read in detail why my culture does not consider abortion murder and why abortion is the right option in many cases," Imershein explains.

Imershein was a freshman at the University of Pennsylvania when the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, making abortion legal throughout the United States. "In my world abortion was already legal," she says. (Abortion was legalized in New York State in 1970, while Imershein was in high school.) "I didn't appreciate then what was going on."

Later in college, she worked with what was then called the Penn Sexuality Center, a joint project between the school's psychology and OB-GYN departments to teach undergraduates how to provide peer counseling in sexuality, contraception, and reproductive health options. And when she graduated from Emory University with her doctorate in 1980, she was part of a new wave of women entering medicine in large numbers. The influx was a result of the women's rights movement—which challenged the standards for the medical treatment of women—as well as the representation of women in the field. Just a handful of years earlier, in 1972, Title IX passed, prohibiting schools from discriminating on the basis of sex.

"The flyer said that I was a 'murderer worse than the KAPOs in the concentration camps.'"

After her residency at NYU's Bellevue Hospital, Imershein moved to Washington, D.C. She married her husband, Mark, in 1985 and her daughter and son were born soon after. For the next two decades, she was an OB-GYN in private practice with fellow doctor Alan Birnkrant, providing abortions when needed. But once her children were finishing college in the late aughts, Imershein went looking for a career change.

It all came together over the course of a few coffee meetings with Willie Parker, then the director of Planned Parenthood Metropolitan Washington. When she told Parker she was interested in a career switch, he walked her through the practicalities of leaving her private practice to perform abortions full-time.

Parker, an OB-GYN and devout Christian, provides abortions to women in the Southern states with the most restrictive abortion laws. Though he admits he once believed abortions were morally wrong, he eventually came to see providing abortion care to women in need as his "life's work" (the title of his newly released memoir). Imershein appreciated his directness: "He didn't do abortions, then he realized there were women in need. Very matter of fact."

There are risks that come with being an outspoken abortion provider in the United States, and Imershein has had her share of frightening run-ins with pro-life advocates. In the summer of 1995, an unknown group distributed flyers in the neighborhoods of OB-GYNs throughout the D.C. area, calling out physicians by name.

"The flyer said that I was a 'murderer worse than the KAPOs in the concentration camps'—so worse than the Jews that were overseers of other Jews during WWII," she says. A similar flyer, covered in feces, appeared on Birnkrant's door. "I was scared," Imershein says. "Doctors were being murdered." In the spring of 1993, Dr. David Gunn was shot to death by an anti-abortion protestor outside of his clinic in Pensacola, Florida. Dr. George Tiller of Wichita, Kansas, whose clinic had been firebombed in the 1980s, was shot in both arms later that year. He was later killed by an anti-abortion activist during a church service in 2009. Most recently, in 2015, a man who declared himself a "warrior for babies" killed three people in a shooting at a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

'Supporters at a vigil for the victims of the 2015 Planned Parenthood shooting.'

Fortunately, the office building housing the Falls Church clinic is surrounded by private parking space, meaning picketers must stay on the sidewalk and can't stand outside the door. But their numbers have increased since the 2016 presidential election. "Some of the protesters yell, but we just ignore them," says Imershein, who no longer fears for her safety inside the "buffer zone" of the beltway.

"Maybe I just have my head in the sand," she says. "But I am so morally committed to providing this care and using my medical skills in a way that is so empowering, and wow, I get told 'Thank you' every day on top of it. How cool is that? When I start being more afraid for myself than the women who need me, I am giving in to the antis."

Imershein doesn't care what anti-abortion advocates believe, but she despises the use of religious freedom as an argument for impeding access to abortion. She calls it "religious intrusion."

"Religious freedom is the freedom to be left alone, not the freedom to create laws based on one group's religion," she argues. "I don't think if you cut off your own arm you will be jailed, or if you attempt suicide you will be jailed. But if you try to self-abort, you can be put in jail in some states." In fact, 38 states allow a person to be charged with homicide if they're deemed responsible for the unlawful death of a fetus, and many of those laws allow the formerly pregnant woman herself to be charged. At least a half a dozen women in the United States have been arrested and charged after attempting to self-induce an abortion with illegally obtained abortifacients, including a Virginia woman arrested in late March on felony charges of "producing abortion or miscarriage."

RELATED STORIES

These intrusions on women's health have increased since Donald Trump took office, according to Imershein. In his first week, the new president reinstated the "global gag rule," a Reagan-era ban on federal funding for international health organizations that perform abortions. And in March, Vice President Pence cast a tie-breaking vote in the Senate to give states permission to withhold federal funds from Planned Parenthood facilities.

"I wake up every morning angry and frustrated at what is happening and what I see as the writing on the wall for women's health, women's rights, women's ability to control their bodies," Imershein says. She strongly believes in the importance of training the next generation of OB-GYNs and believes that "every OB-GYN should learn how to do an abortion," not least of all because every professional organization related to the field says knowing how to perform them is a basic skill requirement. "You wouldn't become a cardiac by-pass surgeon and then limit your practice if you were religiously or morally against blood transfusions," she explains.

In the last academic year, she taught a class in reproductive health at GWU's public health school. She tells me about one of her students, who said at the beginning of the course, "I think abortion is wrong and I'm trying to keep an open mind. Maybe you can convince me it's not."

"I don't want to convince you it's right or wrong, that's your values, your religion, your upbringing," Imershein replied. "What I want to show you is that the scientific evidence says that keeping it safe, legal, and available is good for public health."

Follow Marie Claire on Facebook for the latest news, fascinating reads, video, and more.

-

Ana de Armas Just Revived Fashion's Favorite Sneaker Trend

Ana de Armas Just Revived Fashion's Favorite Sneaker TrendShe found another low-key way to wear it.

By Hanna Lustig Published

-

True Life: I'm Obsessed With Bella Hadid's Bags

True Life: I'm Obsessed With Bella Hadid's BagsFrom Coach purses to Saint Laurent totes, I want them all.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

-

How to Help Those Who Lost Everything

How to Help Those Who Lost EverythingStories from the frontlines of natural disasters.

By Rose Minutaglio Published

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

By Emily Tisch Sussman Last updated

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

By Tanya Benedicto Klich Published

-

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

By Sen. Tammy Duckworth Published

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

By Beth Silvers and Sarah Stewart Holland, hosts of Pantsuit Politics Podcast Published

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan Published

-

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water

My Family and I Live in Navajo Nation. We Don't Have Access to Clean Running Water"They say that the United States is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Why are citizens still living with no access to clean water?"

By Amanda L. As Told To Rachel Epstein Published