The Accidental Sex Offender

It was a classic teenage love story. He was a football star, and she was a cheerleader. They met, they fell in love, they started having sex. And then the cops got involved. Fifteen years later, they're still paying the price.

Frank Rodriguez cannot coach his children's soccer teams. He can't get a job at a major corporation. He can't leave the state without registering with local law enforcement. A married father of four girls, he is a convicted sex offender. Neighbors can find his name and address on a public registry online.

His crime? Sleeping with his high school sweetheart 15 years ago. At the time, Frank was 19 years old, a recent high school graduate in the town of Caldwell, Texas. That's when he first had sex with Nikki Prescott, his future wife. The two had been dating for nearly a year; the sex was consensual. However, the legal age of consent in Texas is 17, and Nikki was just shy of 16. Nikki's mother, worried that her daughter's relationship with Frank was getting too serious, reported Frank to the police. She expected the cops to issue a warning, but instead she set in motion a legal nightmare from which Frank would never recover. He became a registered sex offender — for life.

Today, Nikki, 30, and Frank, 34, both say they unequivocally support laws that put sexual predators behind bars and protect children from attacks. "The registry isn't a bad thing," says Nikki. "It's a good thing. It's just that Frank shouldn't be on it."

Nikki and Frank's predicament is not an isolated incident. Across the country, young lovers are increasingly finding themselves caught in the nation's complicated web of sex-offender laws. Teenagers wind up on the public sex-offender registry, alongside violent predators, pedophiles, and child pornographers, for having consensual sex with an underage partner (or, sometimes, for streaking or sexting — sending racy self-portraits, which can be considered child pornography). The stigma of the sex-offender label is difficult to shed: "Once you're on the registry, good luck trying to explain it," says Sarah Tofte, who has studied sex-offender laws for the nonprofit group Human Rights Watch. "It's like you're in prison proclaiming your innocence. People think, Right, that's a likely story. Especially potential employers."

There are now more than 650,000 registered sex offenders nationwide. There are no reliable statistics on the number of juveniles — but the problem is clearly on the rise. Each of the 50 states now has at least one grassroots group dedicated to getting young people — many high school age, but some under the age of 10 — off the registry. The effort includes judges and other legal experts who say they have seen the problem often enough to persuade them that the system needs adjustment.

Still, the problem is poorly understood. Partly out of embarrassment, some parents don't want to talk about this issue — even as they work to try to remove their own children from the registry. To get some answers as to the extent of the problem, we conducted our own survey, state by state. What we found: Not all states register juveniles, and of the 34 that do, only 23 keep track of the number of juveniles on the registry. In those 23 states, there are nearly 23,000 registered juveniles. No states monitor whether the number of juveniles is on the rise or not, but one state, Oregon, provided an estimate, reporting a 70 percent jump in that state since 2005.

Undoubtedly, some of the juveniles on the list are guilty of violent sexual crimes. The grassroots movement is trying to help a different group of people: high school students who get labeled as sex offenders for teenage sexual behavior that can be technically criminal, but which, activists argue, should fall into a different category. Under the current system, kids' futures are being ruined, says William C. Buhl, a recently retired Michigan circuit judge who became an activist after overseeing 12 convictions of teenagers for consensual sex. Says Buhl, "What we have done, to young men, mostly, is destroy their lives, for somewhat common behavior."

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Nikki Rodriguez remembers the night that sparked her embattled future — the night she first met Frank. At a mutual friend's house one evening on spring break, she and Frank began chatting, and quickly clicked. She was a 15-year-old freshman in high school, a self-described "clumsy" cheerleader. He was an 18-year-old football star, a confident, outgoing high school senior. They soon began calling each other every day. At the time, Nikki lived with her mother, stepfather, and four siblings on the grounds of a church camp that the family ran in Caldwell, a town of around 3,500 people.

"Frank was different," Nikki says. "He would pick flowers for me at the bus stop and bring them to school. At lunch, he came and sat with my friends and me, not with the guys." After nearly a year together, she and Frank had sex. They had no idea about crime or the consequences. "We were just madly in love," says Nikki, while standing on the sidelines of a soccer game in Caldwell on a windy Saturday morning. Watching her 11-year-old daughter, Analissa, bounce around the field, she adds, "Everyone was doing it."

When Nikki admitted to her mother, Melissa Ostman, that she was sleeping with Frank, tension flared. Ostman didn't think her daughter was ready for a sexual relationship, and the two began arguing frequently. "It's just that Nikki was so young," Ostman says. "I liked Frank from day one, but I wanted them to cool off."

One night, after Nikki and her mother had yet another argument, Ostman snapped. "Nikki and Frank were supposed to bring her sister home from the fair, but they left her there and went off together," she says. "I said, 'That's it.' I was getting so mad." Fed up after months of feuding, she says, she drove her daughter to the police station that night and reported Frank for having sex with a minor. "It was the only thing I could think of to get Nikki to listen to me," she says. "I wanted her to know I was serious." She thought the police would simply scare Frank, giving him a stern warning. "If I had known the implications," she says, "I wouldn't have done it."

Nikki remembers the police interrogation. "The sheriff said I had to give a statement," she says. "I refused." The officer told Nikki she could be arrested, she says, so she replied: "Arrest me." Then, thinking it would help Frank, she told the cops the sex was consensual. After that, she was driven to the hospital to be tested for rape.

The next day, Nikki's mother calmed down. She went back to the police station to rescind her complaint. It was too late. "The police said the state would be taking it from here," she says. "Looking back on it, I just feel horrible. I don't know what the answer is when your kid is 15 or 16 and wants to date. But the answer is not to label the guy a sex offender."

America's sex-offender laws have a noble goal: to protect children from predators. A handful of states have had sex-offender registries since the 1940s, but most states began creating them in the 1990s, after an 11-year-old boy named Jacob Wetterling disappeared while riding his bike in Minnesota. In 1994, Congress created the Jacob Wetterling Act, requiring states to establish registries listing convicted sex offenders. That same year, 7-year-old Megan Kanka was raped and killed by a predator who lured her into his New Jersey home. Two years later, Congress passed Megan's Law, making the registries available to the public.

Other federal acts have followed. The federal rules are broadly defined, and state laws vary widely. In 2006, new federal legislation tried to bring some uniformity to the tangle of state laws. The Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act, also known as the Adam Walsh Act (named for a 6-year-old Florida boy who was murdered in 1981), created minimum standards across the states. However, only seven states have implemented the act to date. A main reason cited is cost: Many states, already struggling to maintain expanding registries, say they can't afford any added administrative costs. The government has said that states that aren't compliant with the act will lose a chunk of federal funding, effective as of July this year.

In the meantime, the effectiveness of individual state registries has become subject to debate. Patty Wetterling, a child-safety advocate whose son Jacob sparked the Wetterling Act, now counts herself among those voicing concerns. The registries were designed to be "a very useful law-enforcement tool," she says, "but legislators wanting to appear tough on crime have hijacked that intent, have cast a very broad net, and are causing many people tremendous harm." Parents add that teenagers arrested for consensual sex are diluting the registries — making it hard to spot violent predators.

Frank Rodriguez was 19 years old in the fall of 1996 when the police rolled up to his home and arrested him. The eldest of three brothers and two sisters, Frank had grown up in Caldwell, where his parents worked for the city and the school system. Frank had spent his high school summers working on local ranches, and the physical labor served him well on the football field. Known around town as a star lineman and kicker, he was surprised when the police treated him as a criminal instead of a hero.

"The guys who cheered me on at games were treating me like dirt," says Frank, while sitting at a Mexican restaurant on the outskirts of town. It's a Sunday afternoon, and he has been working all weekend, doing carpentry work as a freelance contractor.

After spending the night in jail as a teen, Frank met with his court-appointed attorney, Mary Hennessy. Says Frank, "She told me: You could do two to 20 years if you go to trial. I was like, 'What?'" The attorney advised Frank to plead guilty, meaning he would get seven years' probation. He followed her advice.

Hennessy explains today that while she doesn't think it's fair to label Frank as a sex offender, the state has an obligation to protect children. Local authorities could not ignore the complaint against Frank, she says, even if Nikki's mother tried to take it back.

Once he was labeled a sex offender, Frank faced a slew of restrictions. "I couldn't talk to Nikki. I couldn't go to restaurants, public swimming pools, football games — any places where there might be kids," he says. "I couldn't vote. I couldn't leave the county without permission. My probation officer told me, 'If you even look at a woman the wrong way, you could go to prison.'"

Frank did not have to go to jail. Instead, he was required to perform 350 hours of community service — picking up trash, mowing lawns — and to attend weekly counseling courses with convicted sex offenders and pedophiles. He also had to move out of his family home, since a 12-year-old girl lived there: his own sister.

His father helped him rent a place, and Frank says he became depressed. A recent high school graduate, he had been planning to attend a nearby technical college. Instead, he says, "I just locked myself up in there — my life stopped." After a few months, he spoke secretly on the phone with Nikki, who said she would wait for him. "In my world, it meant everything," Frank says. He managed to get a job with the help of a friend whose father owned a construction company. He began fixing up a home his grandmother owned, then moved in. The day Nikki turned 17, she moved in, too. The reunion was an emotional one, as Nikki had endured a rough year herself: Her relationship with her mother had deteriorated dramatically.

Despite the unusual circumstances, Nikki and Frank's connection grew stronger. "We didn't have anything — but we didn't need anything," Frank says. "We were together." Nikki finished school, then got a job in the county courthouse, where she works today; she and Frank married two years later. The couple's first daughter was born about two years after that. Since Frank was still on probation, it was illegal for him to live in the same home as his baby girl. So he lived there against the law, becoming withdrawn and paranoid, constantly worrying about getting arrested. "My personality changed," he says. "I used to be the life of the party. Now I didn't want to leave the house." A second daughter arrived a year later.

In 2003, Frank's probation came to an end, and he could legally live with his daughters. Still, he needed to go to the police station every year on his birthday to register as a sex offender. Nikki lobbied officials in the courthouse — judges, district attorneys — to clear Frank's name, to no avail. Frank simply fell outside the parameters of Texas law, which stipulated that the accused had to be within three years of age of his underage sexual partner to avoid registration. Frank is three years and two months older than Nikki. A further element of the law said that the accused could avoid registration if he was under 19 years old and his partner was over 13 years old when they had sex. Nikki was 15. But Frank lost again: He was 19.

Nikki and Frank connected with activists, and traveled to the state capital to participate in a public hearing. Still, Frank remained on the Texas registry, his crime listed as "sexual assault of a child."

In recent years, at least 50 grassroots groups have been launched with the goal of changing sex-offender laws. Mothers, shocked to find their sons on the registry for high school sex, note that teens on the registry have trouble getting into college and finding jobs, and often face residency restrictions — such as a ban on living within 1,000 feet of a school. They are also frequent targets of harassment, or worse: A young man in Maine named William Elliott, on the registry for sleeping with his 15-year-old girlfriend when he was 19, was murdered in 2006 by a vigilante. The killer had found Elliott's name on the registry and decided to go hunting for sex offenders before turning the gun on himself.

Some grassroots groups are controversial, as they're lobbying to ease restrictions on all sex offenders, violent or not. But many groups are formed by mothers of high school lovers. Tonia Maloney, who runs Illinois Voices, says her group includes at least 75 mothers of sons on the registry for consensual teenage sex. Francie Baldino, who runs Michigan Citizens for Justice, says her group has around 30 mothers in the same situation. Both women became activists when their own teenage sons were arrested after having consensual sex.

Even kids under the age of 10 have been registered, says Cheryl Carpenter, a criminal-defense attorney in Michigan. She knows a 9-year-old boy who went on a private juvenile registry for playing doctor with a 6-year-old girl. The boy's name can now be removed from the registry, thanks to new state legislation spurred by activists. A similar case is currently unfolding in Wisconsin courts, where a 6-year-old boy is accused of sexually assaulting a 5-year-old girl; the children reportedly said they were playing doctor.

Carpenter, who has managed to free 11 teenagers (all convicted of sexual offenses involving minors) from the registry, now serves on a professional advisory board for the Coalition for a Useful Registry, a grassroots group launched by two Michigan mothers. She estimates that the group includes 150 mothers of sons on the registry for teenage sex. Some of the boys, she says, can now petition for removal from the registry under the state's new legislation.

Activists also note that the age of consent varies among states — ranging from age 16 to 18 — so sex can be a crime in one state and not in another. While the activists say they're not advocating teenage sex, the reality is that a significant percentage of teens are sexually active: A national study by the Centers for Disease Control shows that 28 percent of girls ages 15 to 17 have had sex.

In the past few years, the grassroots groups have managed to get many states to pass laws designed to help high school students. The so-called Romeo and Juliet laws aim to reduce or eliminate the penalties for consensual sex with a minor, provided the couple's age difference is minimal and other parameters are met. While the laws have helped in many cases, activists say, often young people find themselves just missing the parameters of the law in their state.

In Texas in 2009, activists succeeded in getting state lawmakers to pass a bill that tweaked the law — and could help Frank Rodriguez. But when the bill landed on Governor Rick Perry's desk, he vetoed it. This past spring, a revised version of the bill went back to the governor's desk. And this time, in late May, he signed it. The bill becomes law in September — and, for the first time, it gives Frank a chance to petition the court to remove his name from the registry.

Under the new bill, the accused can file a petition if he was within four years of age of his sexual partner and if the partner was at least 15. For Frank, this could be the end of a frustrating 15-year journey, one that has caused tensions on both sides of the family. As Nikki notes, "My relationship with my mom has never been the same."

Her mother agrees. "I walk around every day with this guilt. We don't know yet what kind of effect [Frank's registration] is going to have on the girls," she says, referring to her granddaughters. "Kids can be so mean."

The girls don't yet know their parents' history, although they have hints of it. "They hear us talking," Nikki says, as her daughters bound around the living room on a Saturday evening in Caldwell. "They know something is up. One day my mom came over, and Layla, my 7-year-old, asked her, 'Why did you send my dad to jail?'

"It's been really hard on Frank," Nikki adds, describing how she and Frank have had to explain their situation time and again throughout the years — to teachers, to employers, to parents of their daughters' friends. "He's always wondering what people are thinking." Recently, the family moved to a new home across town, and the neighborhood kids came over every day, until they abruptly stopped. "We wondered, Did their parents see the registry?" Nikki says. "You never know for sure."

When Nikki and Frank learned that the governor of Texas had signed the new bill, they couldn't quite believe it. Now in the process of hiring a lawyer to petition the court, they are reluctant to celebrate their freedom just yet. Says Frank, "I'll believe it when I see it."

How many juveniles are on the sex-offender registry? Find out in the results of our exclusive survey.

To lobby for change in your state, e-mail us at action@marieclaire.com.

Abigail Pesta is an award-winning investigative journalist who writes for major publications around the world. She is the author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down.

-

Hugh Grant Says His 'Notting Hill' Character is "Despicable"

Hugh Grant Says His 'Notting Hill' Character is "Despicable""I just think, 'Why doesn't my character have any balls?'"

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Rihanna Out-Rihannas Herself in a Statement Fur Coat and Polka Dot Dress

Rihanna Out-Rihannas Herself in a Statement Fur Coat and Polka Dot DressWhen it comes to fashion, the singer and entrepreneur is simply competing with herself.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Selena Gomez Dresses Down Her Platform Prada Loafers With a Classic Blazer and Jeans

Selena Gomez Dresses Down Her Platform Prada Loafers With a Classic Blazer and JeansThe 'Only Murders in the Building' star dressed to impress during a pizza dinner date with her sister.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

35 Tasteful Nude Movies That Feel Like Art

35 Tasteful Nude Movies That Feel Like ArtSteamy and sensual, but in an elevated way.

By Kayleigh Roberts Last updated

-

What's 'Bridgerton' Without the Sex?

What's 'Bridgerton' Without the Sex?Season 2 of the Netflix show betrays its romance roots by barely acknowledging or indulging women’s sexual desires that the genre is celebrated for.

By Kathleen Walsh Published

-

The 35 Best Sex Podcasts of All Time

The 35 Best Sex Podcasts of All TimeSome are funny, some are informative, all are NSFW.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published

-

Of Murder and Motherhood

Of Murder and MotherhoodTheir children are gone but these women are united in their fight for justice and answers.

By Katya Cengel Published

-

60 Gifts for Mom She'll Truly Love

60 Gifts for Mom She'll Truly LoveFrom creature comforts to luxe indulgences.

By Sara Holzman Published

-

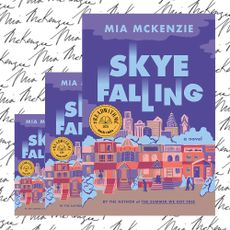

'Skye Falling' Deserves a Spot on Your Summer Reading List

'Skye Falling' Deserves a Spot on Your Summer Reading ListIn July, Marie Claire read Mia McKenzie's 'Skye Falling.' See what the #ReadWithMC community thought about the book here.

By Marie Claire Published

-

What to Know About Adria Biles, Simone Biles' Sister and Biggest Supporter

What to Know About Adria Biles, Simone Biles' Sister and Biggest SupporterHere's what to know about the Team U.S.A. gymnast's supportive, lookalike sis.

By Katherine J. Igoe Last updated

-

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New Eyes

Melissa Moore's 'Life After Happy Face' Podcast Looks at Killers Through New EyesThe true crime expert and daughter of the Happy Face Killer opens up to Marie Claire about destigmatizing the label of 'criminal's kid.'

By Maria Ricapito Published