Why Would a 16-Year-Old Girl Slaughter Her Uber Driver?

Inside the minds of murderous young women.

Dressed in a Cubs shirt and leggings, 16-year-old Eliza Wasni walked into a Walmart in Skokie, Illinois earlier this year and stole a machete and a knife. Surveillance footage shows her moving calmly through the store—knife in one hand, machete in the other. No one stops her. Not even when she leaves without paying.

A blue-eyed, blonde, suburban teen, Wasni must have looked unthreatening. Not a single passerby confronted her as she walked down the street, weapons in each hand. She continued a few blocks west, then called an Uber. Despite the fact that the company does not allow anyone under the age of 18 to request rides, it was Wasni’s third Uber in three hours.

The time was 3:18 a.m. on May 30—nautical twilight, when the faintest stars began to disappear from the sky.

A Hyundai pulled up with 34-year-old driver Grant Nelson behind the wheel. Wasni climbed into the seat behind him, and two minutes later, she allegedly leaned forward and plunged the machete and the knife into the right side of his arm, his torso, his head, and his chest.

In shock, Nelson pulled the car into a condominium driveway and scrambled out. He ran to the building's lobby and banged on doors, screaming, "Help me, help me, I'm going to die!" When the police arrived, they followed a trail of blood to the lawn. There, they found Nelson, who was still conscious and able to tell the officers that his passenger had attacked him. Bleeding profusely, he was transported to the hospital, where he died of his wounds. Police found Nelson’s phone with the Uber app still open—his last passenger was listed simply as “Eliza.”

Wasni had climbed into the front seat of Nelson’s car and attempted to escape, but after driving a short distance, she hit a median and took off on foot. When the police found her, she was a block away, crouched behind an air conditioning unit outside an office complex. Wearing only her bra and leggings, Wasni was still holding the bloody knife and machete, her bloodstained Cubs shirt not far away. She didn't acknowledge the officers. When they demanded she drop the weapons, she ignored them. They had to hit her with a stun gun to bring her into custody.

In the stories we tell about violence, blonde-haired, blue-eyed white girls are the victims. In movies they run away from the attacker. In TV shows they are laid out on tables, their beautiful bodies picked apart for clues to an evil that lies far outside their world.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

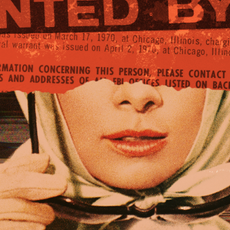

Eliza Wasni’s mugshot, taken in May at age 16

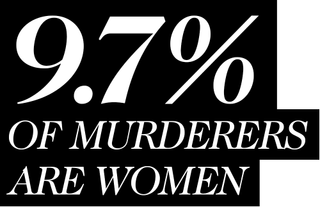

This isn't all fiction. According to FBI crime data, 90 percent of murderers are men. Women are more often the victim than they are the perpetrator. That’s a constant. Despite urgent journalism about the need for increased awareness of female aggressors and teen brutality, there’s no research to support claims that women are closing the violence gap by any meaningful measure. Meda-Chesney Lind, a professor of women’s studies at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, and co-editor of Fighting for Girls: New Perspectives on Gender and Violence, argues that any seeming uptick in assaults can be attributed to an effort to crack down on female violence and criminalize behaviors that had previously been overlooked, like arguing with teachers and fighting with fellow students. Per the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports, arrests of violent female juvenile offenders actually decreased by more than 44 percent between 2006 and 2015.

That it is rare makes cases like Wasni’s all the more sensational and mysterious. We have many ways of understanding male violence, particularly white male violence—there’s the misunderstood teen, the disgruntled husband, the jaded lover, the vigilante, the man who was otherwise good but "snapped." Male aggression is, from a young age, sanctioned, even encouraged. Boys are given toy guns and told to watch action movies, while girls are taught to be sweet and nurturing, given dolls and tea parties. So when women—particularly white women—veer from the narrative of victim into the role of victimizer, we struggle to understand their actions. Writing in When She Was Bad, author Patricia Pearson notes: "We tend…to peg [violent] women as afflicted and mentally ill, while understanding men as willful, immoral, and antisocial." A woman couldn’t possibly just be violent, just choose to commit an evil deed; there must have been a reason, there must be something else at play.

This cultural mythology is rampant. In April, when Donald Trump dropped "the mother of all bombs" on Afghanistan, the Pope criticized the name of the weapon, citing its incongruity: "A mother gives life and this one gives death." If it had been called the father of all bombs, doubtful anyone would have objected.

Aileen Wuornos at age 13 (left); in prison in 1992 (right)

A violent man is a tragedy, but not a novelty. A violent woman, however, is an act of defiance against nature. Her violence is duplicitous: the Siren whose sweet songs lead men to their deaths. Medea murdering her children. Highway hooker Aileen Wuornos shooting at least six men. We regard them as evil in disguise: A machete in the hand of a white girl in leggings. In 2014, when Jerad and Amanda Miller went on a mass shooting spree in Reno, Nevada, a man with a gun who had witnessed the rampage confronted Jerad, not Amanda. But it was Amanda who shot him.

Lind lightly chides me that Wansi’s story would barely be on my radar if the perpetrator were a man. She's right.

Once, while attending a community policing course, I watched a realtor go through a high-tech training simulation. It was like a video game, with a realistic gun, and he had to decide when to shoot and when not to shoot. The scenario was a routine traffic stop in which the realtor discovered that the driver of the vehicle was wanted on a warrant. As the situation escalated, a 10-year-old girl who had been in the car got out and shot at the man. The scenario was over. The realtor was shaken. "I didn't know that was a possibility," he said.

Surveillance footage shows Jerad and Amanda Miller, guns drawn, laying on the floor in an aisle at Walmart during a shootout with police. Courtesy of Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department

Female criminals are even treated differently. Facebook commenters were outraged at the fact that Wasni—a murder suspect with a knife—was brought into custody after merely being tased, in contrast to the shooting deaths of men like Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, who were unarmed when killed. Those men were just men, going about their business. Not men who had left a trail of blood in their wake. Other commenters just as vehemently argued that Wasni was a young girl and therefore must have been compelled toward cruelty by some mediating factor: drugs, mental illness, gangs, abuse. Women are not seen as violent, even when they are.

To be clear: Black women are disproportionately more likely to be victims of violence, but they’re all too often seen as violent aggressors. News outlets don’t narrate their deaths with dramatic monologuing. The idea of the black woman as the angry party is so ingrained it’s a trope. When racism is layered with sexism, the story is more oppressive—black women are never the angels. Meanwhile the narrative around white women is insidious with presumed assumptions of innocence.

Culprits use that to their advantage. Serial killer Karla Homolka, who assisted in the rape and murder of three women with her then-husband Paul Bernardo in the early 90s, portrayed herself as an innocent victim of her abusive spouse. But she plead guilty and was convicted of manslaughter. After serving 12 years of her sentence, she was released from jail, and as recently as March of this year was working as a volunteer at her children's school. Her ex-husband is still behind bars.

A 2015 study published in the Journal of Criminal Justice posited that women who are young, white, or mothers receive what the authors termed "chivalry" justice—a more lenient sentence and lower bond than their male counterparts. Brutality in women has often been legislated and codified in unequal ways throughout history. Lawyer and activist Helena Kennedy explains in her book Eve Was Framed that retaliatory violence by women—violence against a wrongdoer that differs from self-defense because it's committed when the threat isn’t immediate—wasn't even considered by the British courts until recently.

In the most egregious cases, women are believed to be innocent even when they say they aren’t. Look, for example, at Elizabeth Wettlaufer, a former nurse who killed the elderly people in her care. Wettlaufer confided in a childhood friend that she had murdered six people, but he didn't believe her, telling the press he initially though she was "delusional" and that her confession was a "cry for attention." Only after Wettlaufer checked herself into a mental-health facility and psychiatrists called the police did authorities get involved.

In her book Lady Killers, author Tori Telfer notes what a short memory society has for vicious white women. When Wuornos was convicted, America reeled at what some called the first female serial killer. She wasn't the first, though, not even close—there had been Nannie Doss, Mary Ann Cotton, and so many others. But women who take life instead of give it don't fit into our narrative, so we move on and forget.

Instead we focus on what we see most often. Many women I dearly love have horrifying stories of violence at the hands of men, and study after study clearly shows that women are more likely than men to suffer from domestic violence, rape, and abuse. But that makes understanding violent women more imperative, not less. If we can wrap our minds around why women commit harrowing crimes, we can rip apart the suffocating binaries of the pale beautiful victim and the aberrant vengeful monster and give women room to be understood, for better or worse, as themselves.

According to forensic psychiatrist Sigrun Rossmanith, women are more likely to kill at home and their victims are often the people in their care. Women also tend to kill subversively, using methods like poisoning and drowning more often than men. They use guns less frequently.

Interestingly, the fetishization of female violence in pop culture has only clouded these realities. Brutality among female characters is often attributed to years of abuse (see: the women of Big Little Lies) or a protective mothering instinct taken to the extreme (think: Cersi Lannister), when the reality, Lind says, is far more complicated and nuanced.

The truth is that women kill for as many various and unpredictable reasons as men do. A violent woman is not always an abused woman—she might simply be seeking power. She might be plotting a path to a goal and knocking off obstacles along the way. She might be chasing a dark secret thrill.

As Lind points out, all violence, in all people, is part of a larger narrative that lies at the intersection of culture, gender, race, class, income, and all the tiny tragedies that occur in our lives.

I'm fascinated by violent women because for many years I longed to be one. After I learned about the abuse of one of my family members, I often imagined myself wreaking revenge in a Kill Bill–style montage. I didn't do that, of course. Instead I healed through running, weightlifting, and slamming medicine balls. Eventually I sought counseling, but the therapeutic physicality of finding my own strength has never left. I tell Lind that given all that women endure, it's amazing we aren't more violent.

Surveillance footage shows Uber driver Grant Nelson in his car around the time of the stabbing.

Finally we are starting to get portrayals of women that take that nuance and endurance into account. Shows like Netflix's Jessica Jones and, yes, HBO's Game of Thrones depict women as victims and victimizers, engaged in a complicated dance of blood and revenge and power. Pearson points to the recent remake of Wonder Woman, which portrays a woman using violence in a positive way—to fight for those who are victimized. "That’s a good start," she comments, "to acknowledge that women have power and agency."

But, of course, power and agency are only part of the picture. To understand the rest requires unmooring ourselves from the cultural binary of the dead saint or the deviant monster; the victim or the femme fatale; the sweet girl or the bitch.

Eliza Wasni is still in custody. At her indictment hearing on June 21, no motive was given for her crime. She’s being held in a juvenile detention facility where she has reportedly lashed out at the guards, hitting, kicking, and biting them.

Even as she defies every natural law we have—this aggressive teenage girl who murdered a stranger in cold blood, for reasons we can’t fathom—Wasni is being neatly filed into a designated folder. After the news of the murder broke, her social media accounts were deluged with angry commenters accusing her of being a "dumb cunt" who ought to be violated in prison. Whatever the answers are to her violence, Wasni is still only Madonna or whore.

Header: Florida DOC/Getty Images; Frank Gunn/CP/AP Photo; Village of Lincolnwood

Lyz Lenz is the author of Godland and Belabored. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, Pacific Standard, and Buzzfeed. She lives in Iowa, but you can find her on Twitter @lyzl.

-

ALO Is Having a Rare Black Friday Sale—These Are the 19 Best Items

ALO Is Having a Rare Black Friday Sale—These Are the 19 Best ItemsShop these styles before they sell out.

By Emma Walsh Published

-

The Rumor That Ariana Grande Was Paid More Than Cynthia Erivo for 'Wicked' Has Been Shut Down

The Rumor That Ariana Grande Was Paid More Than Cynthia Erivo for 'Wicked' Has Been Shut DownThe rumor claimed that Grande was paid 15 times as much as Erivo for the movie.

By Kayleigh Roberts Published

-

It's Official: All The Cool Girls Are Wearing Red Wine Supernova Hair For Winter

It's Official: All The Cool Girls Are Wearing Red Wine Supernova Hair For WinterThe season's top hair color trends are painfully chic.

By Jamie Wilson Published

-

Love Has Lost

Love Has LostQuasi-religious group Love Has Won claimed to offer wellness advice and self-care products, but what was actually being dished out by their late leader Amy Carlson Stroud—self-professed “Mother God”—was much darker. How our current conspiritualist culture is to blame.

By Virginia Pelley Published

-

We Should Have Known About J.K. Rowling's Views, Thanks to Her Under-the-Radar Book Series

We Should Have Known About J.K. Rowling's Views, Thanks to Her Under-the-Radar Book SeriesValid criticism has been written about JK Rowling's transphobic comments, and our relationship to Harry Potter. But what about her Robert Galbraith books?

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Kate Middleton's Most Controversial Moments

Kate Middleton's Most Controversial MomentsMany of them have to do with her fashion choices.

By Alex Warner Published

-

The 'Dirty John' Cast vs. The Real People They Played

The 'Dirty John' Cast vs. The Real People They PlayedThe second season of the hit podcast-turned-drama looks intense.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

The Great Escape

The Great EscapeAmid a rash of women fleeing oppressive families in the middle east, the case of Princess Latifa, who has tried to run away twice, has been splashed across headlines around the world. In exclusive interviews with her friends and family, Marie Claire goes behind the scenes of her last attempt and their fight to #FreeLatifa.

By Abigail Haworth Published

-

The Hollywood Con Queen

The Hollywood Con QueenShe tormented studio executives, actors, makeup artists, security guys, photographers, screenwriters, athletes, even bobsledders and scuba divers for years—until corporate investigator Nicoletta Kotsianas was put on the case.

By K.J. Yossman Published

-

What It's Like to Grow Up in a Cult

What It's Like to Grow Up in a CultIn her new book, To the Moon and Back: A Childhood Under the Influence, Lisa Kohn describes her journey into and out of the infamous Unification Church.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

This Is How Real-Life Resistance Witches Say They're Taking Down the Patriarchy

This Is How Real-Life Resistance Witches Say They're Taking Down the PatriarchyAnd why one witch believes their hex on Trump worked.

By Megan DiTrolio Published