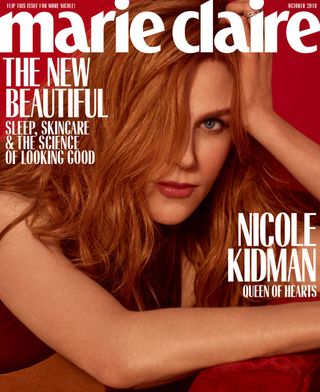

Nicole Kidman and her husband, the country music star Keith Urban, like to play a little game. Say they’re talking about a guitarist: “When I say to him, ‘What kind of guitarist is that person?’ we do this,” she says, patting her head, patting her heart, and then motioning ... downward. “Head, heart, or—” she cocks an eyebrow. “It’s a great way to describe different artists, right?"

Salvatore Ferragamo dress and belt; Ring Kidman’s own.

It is. And it also begs a question: What kind of artist is she? “Well, I always say I’m a pretty even mix, but I’m probably dominated by that,” she says, with one hand over her heart. “If you don’t come from a feeling place, you just end up with an enormous amount of technique.

“I have this,” she says, tapping her head again, “but that can be overruled. It fluctuates too. I have a strong sexuality. It’s a huge part of who I am and my existence."

Anyone who has seen Kidman in HBO’s hit series Big Little Lies has witnessed all three elements at play, but offscreen her sexuality also manifests in more innocent ways, like when she sees her husband—who crashes our interview at Noshville Delicatessen in Nashville, where the couple has lived since they married in 2006. “Excuse me,” Urban says, approaching the booth. “Can I clear these dishes for you?” Kidman beams and pulls him down next to her. They eat here often enough that the burgundy-haired hostess, Linda, barely bats an eye when they enter but can’t help exhaling dreamily when they leave: “I could stare at him all day long. He’s just the most beautiful man!”

Givenchy jacket and dress.

As for Kidman, on this sticky day, she seems to exist in a different climate, wearing her pale-blond curls swept up at the nape of her neck and a charcoal blazer despite the heat. If the other diners have noticed a movie star eating among them, they aren’t doing anything about it, which is one reason why Kidman loves living here. It’s hardly a quiet city—on any given day, the streets are filled with tourists and Pedal Taverns powered by drunk bachelorettes—but it isn’t crawling with paparazzi, like L.A. or New York. It is crawling with country-music stars, many of whom like this particular diner. “You have Vince Gill, who comes every day,” Kidman says, forking some fruit. “He’s usually here for breakfast, so I thought I’d see him.”

Kidman now considers Nashville her hometown and her two daughters with Urban, 10-year-old Sunday Rose and seven-year-old Faith Margaret, Nashvillians. (For souvenir shopping, Kidman recommends a place downtown where one daughter got her first pair of pink cowboy boots.) The family home has a recording studio for Urban. Kidman used it herself while singing on Keith’s 2017 track “Female.” “I was eating breakfast and went down in my pajamas,” she says. “Yeah, I’ll do anything for him."

In the great actors, there’s always the concurrent contradictions of shyness and showmanship, and acute sensitivity and internal steel. [Nicole] is brave on behalf of the truth, and that clarity is what makes her so compelling.

“I have a very sort of quiet life, I suppose,” she adds. “I try to live a soulful, artistic life.” That means “trying to raise my daughters in a really conscious, present way. Time becomes so precious as you get older,” she elaborates. It also means signing on to projects that resonate with her deeply. “I mean, I feel probably more now than I ever have. I’m incredibly sensitive to the world and to the way in which we’re all navigating together as people. Artistically, I can make statements.”

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

Statements like “Love is love”—the message of her new film Boy Erased (out November 2), directed by Joel Edgerton and based on Garrard Conley’s 2016 memoir about being a Baptist pastor’s son (played by Lucas Hedges) who is pressured to undergo gay conversion therapy in Arkansas. Kidman plays his torn mother; Russell Crowe plays his intolerant father.

Salvatore Ferragamo dress and belt; Ring Kidman's own.

“I waited a long time to be married to Nicole,” Crowe jokes. The actors have known each other since traveling in the same circles in Australia, where director Jane Campion encouraged a young Kidman to pursue acting as a career. “We didn’t talk until a jam-packed house party in Darlinghurst. She was 19, maybe,” he recalls. “I say we talked, but I actually don’t think I got more than a word or two out. She’s kind of held me spellbound ever since.”

It’s a subtle kind of magic she casts in person, not so different from the spell she casts on screen, whether she’s playing a fame-hungry weathercaster in To Die For or Virginia Woolf in The Hours (a role for which she won an Academy Award). “Nicole’s acting is too seamless to describe these days, really,” Crowe says. “She is so consummate in how she inhabits characters. In the great actors, there’s always the concurrent contradictions of shyness and showmanship, and acute sensitivity and internal steel. She is brave on behalf of the truth, and that clarity is what makes her so compelling.”

Brave. It’s different from being fearless. Kidman experiences fear. “Crippling fear at times,” she says. “But at the same time, I was raised by stoics.” The actress, who was born in Hawaii, grew up in Sydney, the eldest daughter of a biochemist father and a nurse-educator mother. In particular, she credits her late father, who later became a psychologist, with teaching her about stoicism at an early age. “It’s a philosophy, a way of behaving and being in the world, which I kind of don’t have,” she says wryly. “I have a little bit of it, but I have far more of, like, ‘Oh, my God, how am I going to get through this? I can’t get through this! I can’t get up!’ And then I think, ‘Get up!’” She shakes her head. “I think once you have children, your resilience is built, and your ability to go, ‘OK, I can’t wallow...and I certainly can’t get into bed for a week and never get out.’”

Still, resilience is a quality she has been building in herself for along time. “I’ve had artistic failures,” Kidman says. She has endured painful trials in her personal life as well, some of which she has spoken about openly, such as her fertility struggles and miscarriages during her marriage to Tom Cruise. After marrying in 1990, they divorced in 2001, and their adopted children, Isabella, now 25, and Connor, 23, opted to live with Cruise. Even today, Kidman is the subject of intense scrutiny when it comes to her relationship with her older children. “They’re adults now, married and off in their own lives,” she says. “They’re totally grown-up people.”

I get to live my life, but I get to go into other people’s lives too. They’re transient, but I absolutely live those lives.

After brunch, she’s heading to New York City to see her “Mumma,” whom she has flown in, along with some friends, from Australia. “I’m on daughter duty for the next two days,” Kidman says. “I’m going to take her to the theater to see Carey Mulligan in Girls & Boys. I’ll take her shopping—you know, things that you do.” While in the city, she also plans to visit with Naomi Watts, one of several Australians Kidman counts among her closest friends and collaborators. (Friends call them“Nic” and “Nai.”) “This concept in Australia that goes back a long way is mateship,” says Bruna Papandrea, an executive producer on Big Little Lies (along with Kidman and Reese Witherspoon) who’s also part of that group. “Friendships are like family.” And Kidman is a crucial part of that family, in both Australia, where she and Urban own an operating farm in New South Wales, and the U.S.

Salvatore Ferragamo dress and belt; Ring Kidman's own.

Papandrea recalls one time in particular when Kidman was there for her. “When I really struggled to get pregnant, and I had multiple miscarriages, I remember at one of our other friends’ weddings being completely bereft and having that moment where you think it’s not going to happen,” she says. “And I remember [Nicole] taking me in her arms and just saying, ‘It’s going to be OK; you’ll make a family in the way you can,’ and how significant that was in that moment.

“You have to have empathy as a human to show empathy as an actor,” Papandrea adds.

On-screen, Kidman’s empathy seems to border on telepathy. There’s something almost supernatural about how she embodies her characters. As she puts it, “I get to live my life, but I get to go into other people’s lives too. They’re transient, but I absolutely live those lives.” Once in a while, she steps into a mythical being, like the queen of Atlantis, which she plays in the sci-fi fantasy Aquaman, based on the popular comic of the same name, out in December. (“My way of having a little street cred with my children.”) But she has also entered her share of tortured souls. She recently finished shooting Destroyer, a crime thriller directed by Karyn Kusama in which she plays an LAPD detective who must reckon with bad choices she has made in the past, also out in December. “That was a hell place to exist,” Kidman says. “I was completely in pain, to the point my husband was like, ‘I cannot wait for this to end.’”

It’s probably the Catholic in me, but as soon as there’s some sort of glory or you receive something, you then have got to immediately counteract it with giving back.

For Kusama, seeing Kidman at work was a revelation. “Nicole the movie star exists, and that is one facet of her personal makeup,” the director says. “But another facet that now is becoming the prominent expression of who Nicole is, is Nicole the artist. It’s not that she’s giving up one thing for the other, but you feel that she’s embracing her role as an artist so fully and so completely. Between takes, I would approach her, and she would still be that character in a way. I would see her mind and her heart both working to explore something. And when you see an actor working at that level, it’s thrilling.”

These are the experiences that keep Kidman excited about making movies. “When I have the ability, I always choose to go back to that very basic, in-the-trenches filmmaking,” she says, eyes sparking like blue fire. And lately, she has stepped up her efforts even more to support female filmmakers and tell women’s stories with her Blossom Films production company. (With approximately 50 movies as an actor to her credit, she just signed a first-look film and TV deal with Amazon Studios, which recently greenlit a TV series adaptation of Janice Y.K. Lee’s The Expatriates.)

Kidman traces her own feminism back to her childhood in the 1970s, when her mother used to make her and her younger sister, Antonia, hand out leaflets advocating for political candidates who supported women’s rights. “We’d get teased at school: ‘Oh, your mom is so radical,’” Kidman says. “At the time, we’d roll our eyes and be embarrassed. But my sister and I are both advocates now. It was an incredible gift to be given.”

I look at those films that Polanski made, and they’re amazing. I’m sort of navigating through it myself with my own moral compass. What do you do? Do you ban it? Or see it as art? Or judge it in this time looking back at that time? I have no answer.

As a Goodwill Ambassador for U.N. Women, Kidman has long been a behind-the-scenes champion of women’s rights, but she is becoming louder in her activism. In her best-actress acceptance speech for Big Little Lies at this year’s Golden Globes, she broadcast her feminism to the world, touching on everything from domestic abuse to the power of female friendship. Some of these issues are baked into the first season of Big Little Lies, even though the show and the book it’s based on predate #MeToo. (A second season, with Meryl Streep joining the cast, has finished shooting.) But Kidman’s character, Celeste—who at once lusts for and lives in fear of her violent husband, played by Alexander Skarsgård—quickly became a part of the conversation about power dynamics and sexual and domestic abuse. “I think that’s just when culture and storytelling collide—probably storytelling igniting parts of it and unraveling parts of it. Domestic abuse, or any sort of abuse, and that misuse of power...it’s insidious,” says Kidman, who also received an Emmy for her role. “The day after I won, I was in San Francisco doing a fundraiser for domestic violence. It’s probably the Catholic in me, but as soon as there’s some sort of glory or you receive something, you then have got to immediately counteract it with giving back.”

Last October, following multiple allegations against Harvey Weinstein, Kidman publicly showed her support for “all women...who speak out against any abuse and misuse of power, be it domestic violence or sexual harassment in the workforce.” She didn’t reference Weinstein by name and made no mention of being harassed herself by the producer, but they worked together on many films, including Cold Mountain, The Others, and, most recently, Lion.

Fendi dress.

The movement has sparked debate on how we should look at art made by alleged abusers. “I look at those films that Polanski made, and they’re amazing. I’m sort of navigating through it myself with my own moral compass,” she says. “What do you do? Do you ban it? Or see it as art? Or judge it in this time looking back at that time? I have no answer.”

But she does have questions. One of her favorites: “‘What do you mean?’ And ‘I don’t understand.’ And ‘Teach me,’” she says. “Those are really important things to constantly be saying. I’m willing to learn. Since I was a kid, I’ve loved learning, growing, broadening, understanding, being challenged, being dissected. And I’ve had some of the greatest teachers in the world.”

The late Stanley Kubrick, who directed her in Eyes Wide Shut, was one. “He came into my life and was like, ‘OK, I’m going to make a lot of your beliefs unstable right now for the reason of making you teachable,’ which is a great place to exist in,” she says. Campion, who directed her in The Portrait of a Lady, is another. “One of the great minds,” Kidman says. “She’s got an enormous amount of wisdom.” The actress also tells a story about the late novelist Philip Roth, whose novel The Human Stain was the basis for the eponymous movie in which she starred. As they were getting to know each other, she used to ask the author one persistent question: “‘But why, Philip?’” she recalls. “And he would go, ‘Nicole, Why is the worst question.’” He later presented her with a copy of The Human Stain, which he had inscribed with the words “Why not?”

“I sort of live by that now,” she says, smiling. “Why not?”

This article originally appears in the October issue of Marie Claire, on newsstands September 20.

-

Katie Holmes Does Outfit Repeating for Spring (Somewhat)

Katie Holmes Does Outfit Repeating for Spring (Somewhat)If the actress can re-shop her favorite pieces, then so can everyone.

By India Roby Published

-

Taylor Swift Says 'The Tortured Poets Department' Is the End of Her “Fleeting and Fatalistic” Era

Taylor Swift Says 'The Tortured Poets Department' Is the End of Her “Fleeting and Fatalistic” Era"This period of the author’s life is now over, the chapter closed and boarded up," she says.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Who Helped Taylor Swift Write ‘The Tortured Poets Department’? One Co-Writer Speaks Out After Album Release

Who Helped Taylor Swift Write ‘The Tortured Poets Department’? One Co-Writer Speaks Out After Album Release"We started working on these songs over two years ago and it feels like they have kept us company..."

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

How Timothée Chalamet's "Emotional Intelligence" Will Transform the Character of Willy Wonka

How Timothée Chalamet's "Emotional Intelligence" Will Transform the Character of Willy WonkaLiterally perfect casting.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Adam Sandler Brought His Wife Jackie and Lookalike Daughter Sunny to 'The Out-Laws' Premiere

Adam Sandler Brought His Wife Jackie and Lookalike Daughter Sunny to 'The Out-Laws' PremiereSo cute!

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

'SATC' Star Evan Handler Says He'll "Welcome" Kim Cattrall's Return on His TV Set

'SATC' Star Evan Handler Says He'll "Welcome" Kim Cattrall's Return on His TV SetShe didn't see anyone while filming her cameo.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

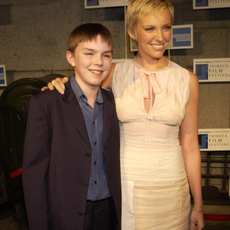

Nicholas Hoult Told Toni Collette He Still Thinks of Her as His Mom When He Watches One of Her Movies

Nicholas Hoult Told Toni Collette He Still Thinks of Her as His Mom When He Watches One of Her MoviesI love this so much.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Everyone Wants Lindsay Lohan on Season 3 of 'White Lotus,' And It Could Actually Happen (If We're Lucky)

Everyone Wants Lindsay Lohan on Season 3 of 'White Lotus,' And It Could Actually Happen (If We're Lucky)Please??????

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

An 'American Idol' Contestant Called Out Katy Perry for "Mom-Shaming" Her

An 'American Idol' Contestant Called Out Katy Perry for "Mom-Shaming" HerShe was really upset by the comment.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

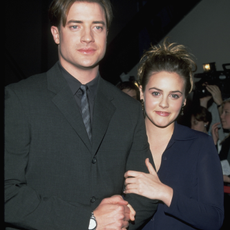

Alicia Silverstone Would Totally Do a Sequel to The '90s Rom-Com She Starred In Opposite Brendan Fraser

Alicia Silverstone Would Totally Do a Sequel to The '90s Rom-Com She Starred In Opposite Brendan FraserDid you guys know about this movie??

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Jennifer Coolidge Addressed the Fan Campaign for Pamela Anderson to Play Her Sister on 'White Lotus'

Jennifer Coolidge Addressed the Fan Campaign for Pamela Anderson to Play Her Sister on 'White Lotus'She's a big fan, too.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published