The Rise of the Millennial Mortician

Caitlin Doughty thinks we should get closer to our dead loved ones.

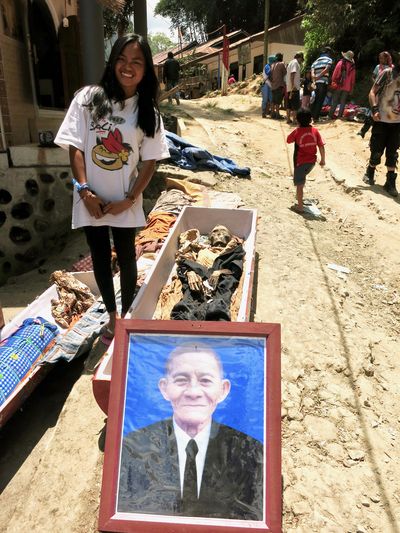

For most of us, a trip to a remote village in Indonesia to witness locals disinter their dead relatives’ mummified bodies and then hang out with them as though they were alive would be an alarming—if not completely existential—experience.

For Caitlin Doughty, it was “the holy grail of corpse interaction.”

Admittedly, she doesn’t know how she would feel about kicking it with a relative’s corpse herself, but the 33-year-old mortician says of observing the ma’nene’ ritual: “Actually getting to see people so lovingly interact with the reality of death and the dead body," as she did while researching her new book, From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death, "and seeing just how normalized that was—it was my vision made real.”

[pullquote align='center']Doughty favors a more “artisanal” approach to death.[/pullquote]

Doughty favors a more “artisanal” approach to death.

That vision is to upend the “cycle of denial” created by an excessively regulated, profit-driven funeral industry—one that encourages Americans to remain ignorant about the death process by presenting itself as the only (and expensive) option when loved ones pass away. “The American funeral industry is so regulated that it's almost impossible for anyone who isn't a wealthy man or a corporation to open a funeral home,” Doughty explains. "In many states, anyone who wants to open a funeral home has to go to mortuary school to learn how to embalm—even if they're Muslim and that is fundamentally against their religion. Then they have to build a $100,000 embalming facility, even if they will never offer the service. The barrier to entry is so high that nobody who actually represents the communities who are dying can get in.”

Doughty witnessed the ritual of ma'nene' in Tana Toraja, Indonesia.

Over the past decade, Doughty has risen—first as an internet personality, then through her bestselling 2015 memoir Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory, and most recently with her progressive funeral parlor, Undertaking LA—to become the young, hip face of the “alternative death movement.” Death-positive advocates like Doughty favor a more empowered, community-oriented, “artisanal” approach. Undertaking LA offers a variety of alternative funeral options, like home funerals.

Doughty’s own home (an apartment in Los Angeles) is exactly what you might imagine for a millennial mortician: dimly lit but not unwelcoming, with carefully curated, tastefully macabre décor lining shelves and side tables. There’s a pinboard bursting with iridescent dragonfly and beetle corpses, a faceless Amish doll in Grim Reaper robes, a model of a human skull (having a real one, she says, would be ethically dubious), and so many neatly arranged books about death that Norman Bates would be impressed. In short, it’s a Goth Housekeeping photo spread par excellence.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The American funeral industry is so regulated that it's almost impossible for anyone who isn't a wealthy man or a corporation to open a funeral home.

Eternity chronicles death rituals in cultures around the world. (The book’s working title, Around the World in 80 Corpses, seemed a bit too glib in the end.) From the ma’nene’ of Tana Toraja in Indonesia to Mexico’s Dia de los Muertos (which only began its huge parade after the 007 movie Spectre drew expectant tourists) to Crestone, Colorado’s open-air community funeral pyre (the only one in the western world), the rites and traditions Doughty describes in her book make the modest proposals of the alternative death movement—that families simply be more involved in the process of preparing their loved ones’ bodies after death, or at least be open to practices like natural burial or alkaline hydrolysis (water cremation)—seem conservative.

“We have this incredibly sanitized relationship with death, and the fact that we rarely see the dead body, or interact with it in any way, and believe that to be wrong, is a broken system,” Doughty says. “Most people living in America now grew up in this narrow, narrow framework, and I wanted people to understand that there are alternatives.”

A Dia de los Muertos celebration in Mexico

Now that the tides are beginning to turn, with more and more people recognizing and pushing back against the restrictions of the traditional embalm-casket-hearse-wake funeral (since 2015, more Americans have been cremated annually than buried), the global rites and rituals she profiles also demonstrate just how far we still have to go.

“We knew from the beginning that change was going to come slowly,” she says of her and her colleagues’ 20-year campaign to break down Western stigmas. “Are we at the point where everybody's willing to have that conversation and really get into it? No. But we’re at a point where these things are seeping into the zeitgeist. When these traditional funeral homes go under, who's going to replace them? If more women are entering the funeral industry—as they are in droves, really—is it going to become devalued work again?”

That’s a lot of emotional and ethical weight to carry for someone also juggling at least four small businesses. So how does a millennial mortician on a very public, often contentious crusade to uproot a suffocating, centuries-old institution deal with the pressure?

[editoriallinks id='6f2cf496-2a87-4738-b22f-549819b69c99'][/editoriallinks]

RELATED STORIES

“I have a very good therapist,” she says, laughing. “Most of what we work on is me being a public figure. I'm not especially equipped or well-built for it.”

As a female social entrepreneur, she says she’s also trying to unlearn instincts like funneling all her income back into her businesses. This will be the first year her book profits will remain her own income. (A well-funded new Patreon page for the nonprofit also helped.) The funeral home is, after two years, finally sustaining itself. Beyond that, it’s all a question of balance.

“I was looking at my old Amazon orders from 2005 recently, and I was like, Oh wow, I used to be really cool. I used to listen to early-industrial post-punk, watch Murnau movies, and read really decadent literature. I was so curated—until I actually started working in death,” she says. “Now horror seems like a busman's holiday to me. I'd rather watch a good tween movie. When you're speaking death all day, and then also creating content about death all the time, you just need a little pep in your step.”

-

In 'Sinners,' Music From the Past Liberates Us From the Present

In 'Sinners,' Music From the Past Liberates Us From the PresentIn its musical moments, Ryan Coogler's vampire blockbuster makes a powerful statement about Black culture, ancestry, and art.

By Quinci LeGardye

-

Kendall Jenner Has the Last Word on the Best Travel Shoes

Kendall Jenner Has the Last Word on the Best Travel ShoesLeave your ballet flats in your checked bag.

By Halie LeSavage

-

Prince Harry Gave Nephew Prince Louis an Extremely Rare Five-Figure Gift for His Christening

Prince Harry Gave Nephew Prince Louis an Extremely Rare Five-Figure Gift for His ChristeningUncle Harry for the gifting win.

By Kristin Contino

-

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into Strength

Peloton’s Selena Samuela on Turning Tragedy Into StrengthBefore becoming a powerhouse cycling instructor, Selena Samuela was an immigrant trying to adjust to new environments and new versions of herself.

By Emily Tisch Sussman

-

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable Future

This Mutual Fund Firm Is Helping to Create a More Sustainable FutureAmy Domini and her firm, Domini Impact Investments LLC, are inspiring a greater and greener world—one investor at a time.

By Sponsored

-

Power Players Build on Success

Power Players Build on Success"The New Normal" left some brands stronger than ever. We asked then what lies ahead.

By Maria Ricapito

-

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wise

Don't Stress! You Can Get in Good Shape Money-wiseFeatures Yes, maybe you eat paleo and have mastered crow pose, but do you practice financial wellness?

By Sallie Krawcheck

-

The Book Club Revolution

The Book Club RevolutionLots of women are voracious readers. Other women are capitalizing on that.

By Lily Herman

-

The Future of Women and Work

The Future of Women and WorkThe pandemic has completely upended how we do our jobs. This is Marie Claire's guide to navigating your career in a COVID-19 world.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POC

Black-Owned Coworking Spaces Are Providing a Safe Haven for POCFor people of color, many of whom prefer to WFH, inclusive coworking spaces don't just offer a place to work—they cultivate community.

By Megan DiTrolio

-

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?

Where Did All My Work Friends Go?The pandemic has forced our work friendships to evolve. Will they ever be the same?

By Rachel Epstein